ALMA (Atacama Large Millimeter/submillimeter Array)

Astronomy and Telescopes

ALMA (Atacama Large Millimeter/submillimeter Array)

Facilities Links to Other Observatories Selected Imagery References

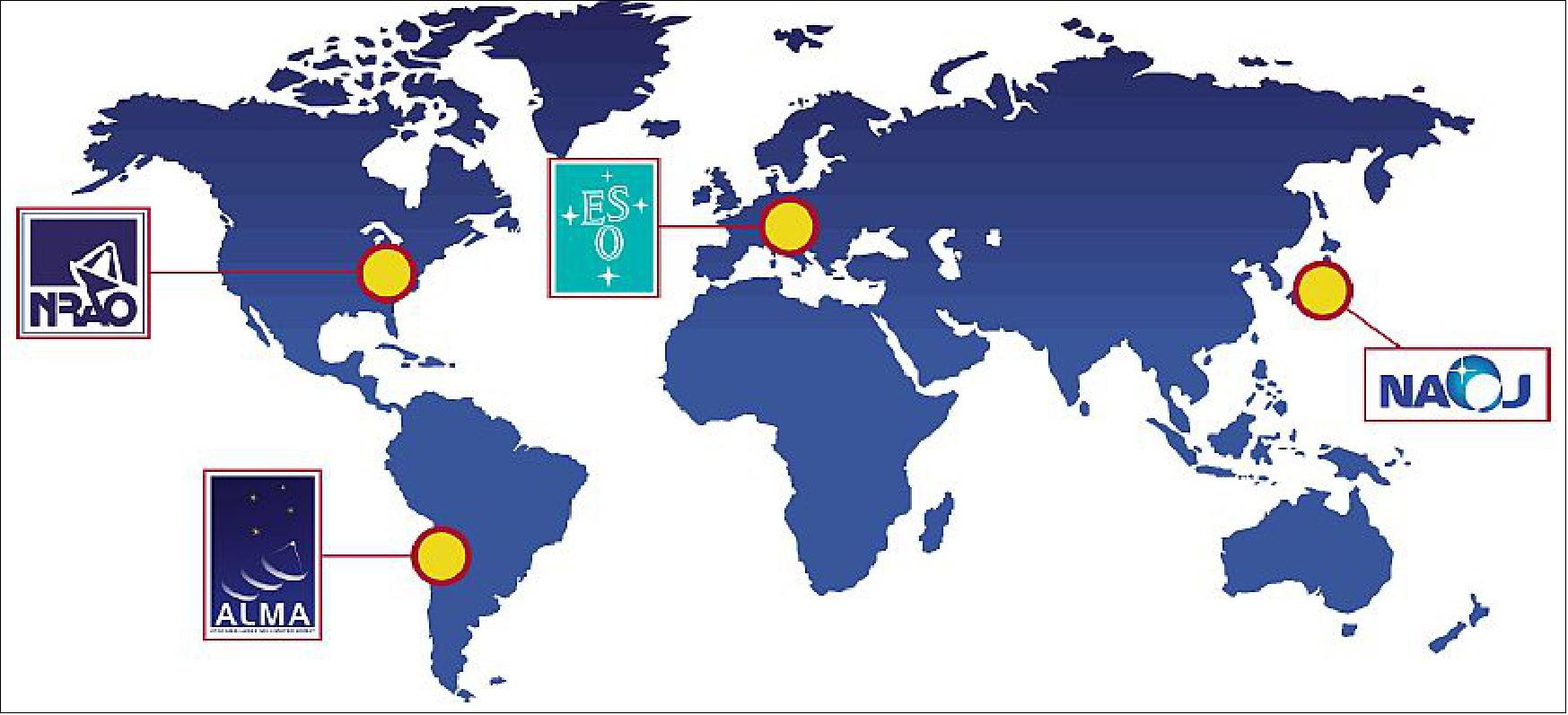

The ALMA Observatory is an international astronomy facility, a partnership of the European Organization for Astronomical Research in the Southern Hemisphere (ESO), the U.S. National Science Foundation (NSF) and NINS (National Institutes of Natural Sciences) of Japan in cooperation with the Republic of Chile. ALMA is funded by ESO on behalf of its Member States, by NSF in cooperation with the NRC (National Research Council) of Canada and the NSC (National Science Council) of Taiwan and by NINS of Japan in cooperation with the Academia Sinica (AS) in Taiwan, and KASI (Korea Astronomy and Space Science Institute) Korea. 1) 2)

ALMA construction and operations are led on behalf of Europe by ESO on behalf of its Member States; by NRAO (National Radio Astronomy Observatory), managed by AUI (Associated Universities, Inc.), on behalf of North America; and by NAOJ (National Astronomical Observatory of Japan) on behalf of East Asia. The Joint ALMA Observatory (JAO) provides the unified leadership and management of the construction, commissioning and operation of ALMA.

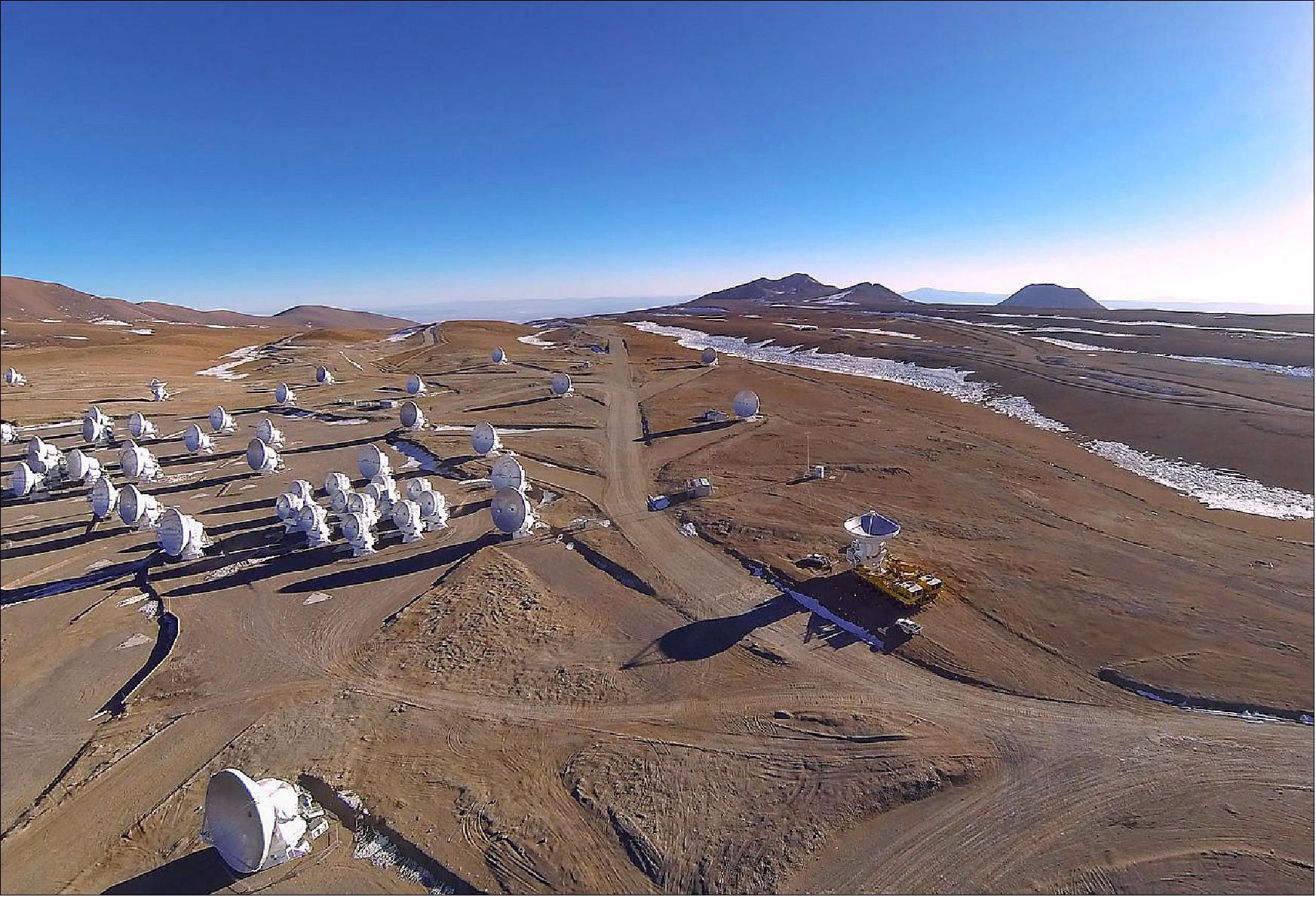

ALMA isthe largest astronomical project in existence, it is a single telescope of revolutionary design, composed of 66 high precision antennas (forming a sparse array of antennas) of 12 m and 7 m in diameter. ALMA is located at a truly unique and unusual place: the Chilean Atacama desert. While the astronomers will operate the telescope from the OSF (Operations Support Facility) Technical Building, at 2,900 m above sea level, the array of antennas will be located at the Altiplano de Chajnantor, a plateau at an altitude of 5,000 m altitude. This location was selected because of many well justified scientific reasons, particularly dryness and altitude. The ALMA site with the average annual rainfall below 100 mm is the perfect place for a new telescope capable of detecting radio waves just millimeters in wavelength. Indeed, radio waves penetrate a lot of the gas and dust in space, and can pass through the Earth’s atmosphere with little distortion. However, if the atmosphere above ALMA contained water, the radio signals would be heavily absorbed – the tiny droplets of water scatter the radio waves in all directions before they reach the telescope, and would degrade the quality of the observations.

Furthermore, the flat and wide land at the ALMA site is suitable for the construction of a large-scale array. Considering these aspects, the ALMA Observatory will not only be unique because of its ambitious scientific goals, and the unprecedented technical requirements, it will also be unique because of the very specific, harsh environment and living conditions in which the most challenging radio telescope array will operate with high efficiency and accuracy.

ALMA is an international astronomy facility, a partnership of the European Organisation for Astronomical Research in the Southern Hemisphere (ESO), the U.S. National Science Foundation (NSF) and the National Institutes of Natural Sciences (NINS) of Japan in cooperation with the Republic of Chile. ALMA is funded by ESO on behalf of its Member States, by NSF in cooperation with the National Research Council of Canada (NRC) and the Ministry of Science and Technology (MOST) and by NINS in cooperation with the Academia Sinica (AS) in Taiwan and the Korea Astronomy and Space Science Institute (KASI).

ALMA construction and operations are led on behalf of Europe (ESO), North America (NRAO/AUI), and East Asia (NAOJ). The JAO (Joint ALMA Observatory) provides the unified leadership and management of the construction, commissioning and operation of ALMA. The JAO coordinates the ALMA Development Program in order to effectively manage the technological evolution of the ALMA facility. Periodically, solicitations (“calls”) are issued by each of the international partners to identify and fund development initiatives (“upgrades”) which will enhance the performance of the ALMA facility. The implementation of ALMA upgrades are assigned on a competitive basis.

Development Status

On 6 November 1963, the initial agreement between the European Southern Observatory (ESO) and the Government of Chile, the Convenio, was signed, enabling ESO to place its telescopes beneath the exceptionally clear Chilean skies.

The birth of ALMA dates back to the end of the 20th century. Large millimeter/submillimeter array radio telescopes were studied by astronomers in Europe, North America and Japan and different possible observatories had been discussed. After thorough investigations, it became obvious that the ambitious projects of all of these studies could hardly be realized by a single community.

Consequently, a first memorandum was signed in 1999 by the North American community, represented through the NSF (National Science Foundation), and the European community, represented through ESO (European Organization for Astronomical Research in the Southern Hemisphere), followed in 2002 by an agreement to construct ALMA on a plateau in Chile.

Thereafter, Japan, through the NAOJ (National Astronomical Observatory of Japan), worked with the other partners to define and formulate its participation in the ALMA project. An official, trilateral agreement between ESO, the NSF, and the National Institutes for Natural Sciences (NINS, Japan) concerning the construction of the enhanced Atacama Large Millimeter / submillimeter Array was signed in September 2004. This agreement was subsequently amended in July 2006.

NAOJ will provide four 12-meter diameter antennas and twelve 7-meter diameter antennas for a compact array (ACA), the ACA correlator and three receiver bands. With the inclusion of the Asian partners, ALMA has become a truly global astronomical facility, involving scientists from four different continents.

• On Nov. 17, 2009, ALMA made its first measurements using just two of the 66 antennas that will comprise the array. As of January 4, 2010, three antennas are working in unison. In October 2011, ALMA has officially opened for astronomers. About a third of ALMA's 66 radio antennas are installed. 6)- ALMA is the largest and most ambitious ground-based observatory ever created with full service provision expected in 2013. 6)

• On 3 October 2011, ALMA opened officially for astronomers - using the partially constructed antenna array.

• ALMA was inaugurated in an official ceremony on March 13, 2013. This event marks the completion of all the major systems of the giant telescope and the formal transition from a construction project to a fully fledged observatory. The telescope has already provided unprecedented views of the cosmos with only a portion of its full array. 7)

• The 66th ALMA antenna was transported to the AOC (Array Operations Site) on 13 June 2014. This is an important milestone for the ALMA project. The 12 m diameter dish is the 25th and final European antenna to be transported up to the Chajnantor Plateau. It will work alongside its European predecessors, as well as 25 North American 12 m antennas and 16 East Asian (four 12 m and twelve 7 m) antennas. 8) 9)

• In March 2015, ALMA combined its immense collecting area and sensitivity with that of the APEX (Atacama Pathfinder Experiment) Telescope to create a new, single instrument through a process known as VLBI (Very Long Baseline Interferometry). In VLBI, data from two independent telescopes are combined to form a virtual telescope that spans the geographic distance between them, yielding extraordinary magnifying power. 10)

• In July 2015, ALMA successfully opened its eyes on another frequency range after obtaining the first fringes with a Band 5 receiver, specifically designed to detect water in the local Universe. Band 5 will also open up the possibility of studying complex molecules in star-forming regions and protoplanetary discs, and detecting molecules and atoms in galaxies in the early Universe, looking back about 13 billion years. 11)

• Nov. 4, 2015: A new instrument attached to the 12 m APEX (Atacama Pathfinder Experiment) telescope at 5000 m above sea level in the Chilean Andes, is opening up a previously unexplored window on the Universe. The SEPIA (Swedish–ESO PI receiver for APEX) will detect the faint signals from water and other molecules within the Milky Way, other nearby galaxies and the early Universe. 13)

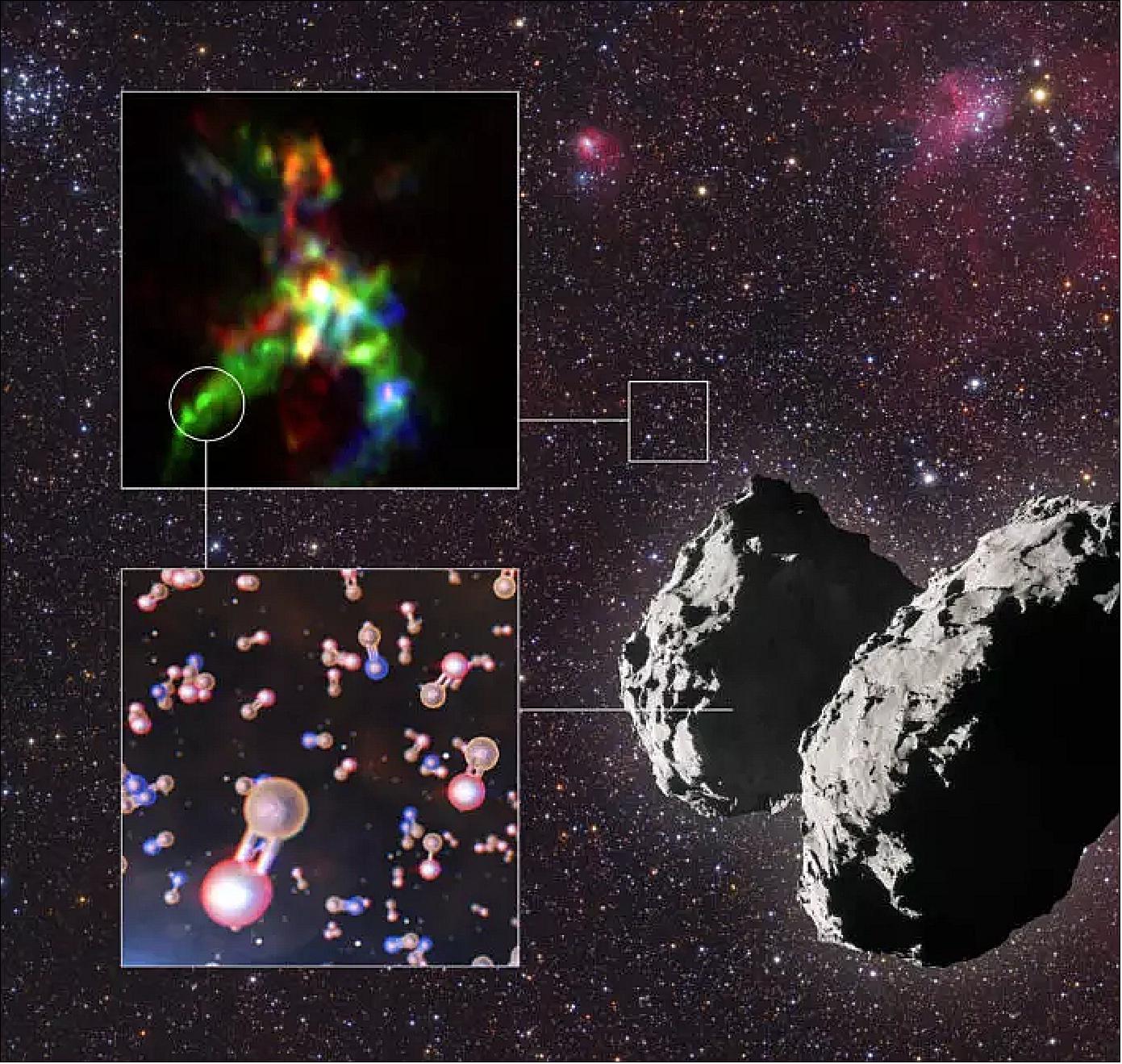

- The SEPIA wavelength region of 1.4–1.9 mm is of great interest to astronomers as signals from water in space are found here. Water is an important indicator of many astrophysical processes, including the formation of stars, and is believed to play an important role in the origin of life. Studying water in space — in molecular clouds, in star-forming regions and even in comets within the Solar System — is expected to provide critical clues to the role of water in the Milky Way and in the history of the Earth. In addition, SEPIA’s sensitivity makes it a powerful tool for also detecting carbon monoxide and ionised carbon in galaxies in the early Universe.

• July 12, 2018: After half a decade of ALMA operations, the original science goals of the observatory have been essentially met. To maintain the leading-edge capabilities of the observatory, the ALMA Board designated a Working Group to prioritize recommendations from the ALMA Science Advisory Committee (ASAC) on new developments for the observatory between now and 2030. 14)

The Working Group concluded, based on the ASAC recommendations, that the science drivers that will support further developments shall be:

- to trace the cosmic evolution of key elements from the first galaxies through the peak of star formation in the Universe;

- to trace the evolution from simple to complex organic molecules through the process of star and planet formation down to solar system scales;

- to image protoplanetary disks in nearby star formation regions to resolve their Earth-forming zones, enabling detection of the tidal gaps and inner holes created by forming planets.

Even with the outstanding capabilities of the current ALMA array, achieving these ambitious goals is currently impossible. The ALMA observatory needs to become more powerful to address these new challenges and stay at the forefront of astronomy by continuing to produce transformational science and enabling fundamental understanding of the Universe for the decades to come.

The top priority upgrades for ALMA will be focused on the receivers (the signal detectors), the digital systems (data transmission), and the correlator (the supercomputer data processor at the heart of the telescope).In addition, to keep up with the new powerful capabilities of the observatory, the ALMA Archive will be further developed, becoming the primary source for the ever-increasing number of publications using advanced data mining tools.

The recently appointed ALMA Director, Sean Dougherty, is very enthusiastic about these new developments being implemented in the coming years, as “they will ensure a front-row seat for ALMA over the next decade, through the development of state of the art technology that will advance our understanding of the Universe. This is an important step in continuing the quest for our cosmic origins”.

The proposed developments will advance a wide range of scientific studies by significantly reducing the time required for the complex observations required by the astronomical community to achieve its ambitious science goals.

“This is an exciting moment in the history of ALMA – says Toshikazu Onishi, Chair of the ALMA Board – as we are advancing the future capabilities of this extraordinary facility we built to explore the Universe.”.

Facilities

Antennas

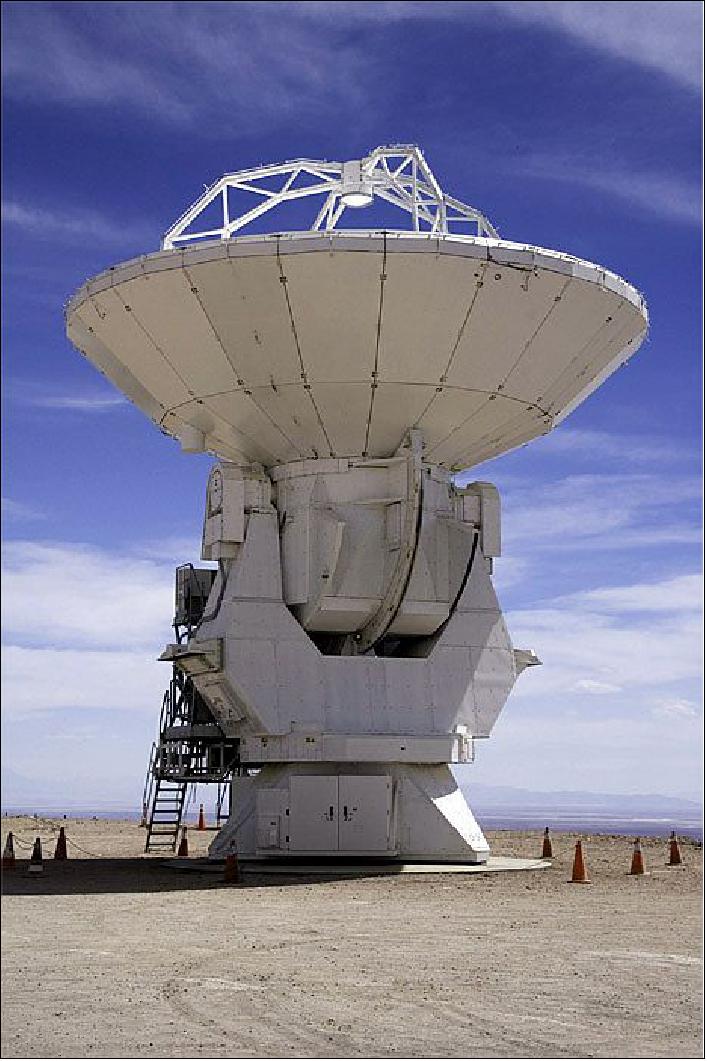

ALMA will be the world’s most powerful telescope for studying the Universe at submillimeter and millimeter wavelengths, on the boundary between infrared light and the longer radio waves. However, ALMA does not resemble many people’s image of a giant telescope. It does not use the shiny, reflective mirrors of visible- and infrared-light telescopes; it is instead comprised of many “antennas” that look like large metallic satellite dishes. 15)

Several antennas have already been installed in the harsh conditions of the 5000 m altitude Chajnantor plateau, and more are under construction at the 2900 m altitude OSF (Operations Support Facility). When ALMA is fully operational, visitors to Chajnantor will encounter 66 antennas, 54 of them with 12 m diameter dishes, and 12 smaller ones, with a diameter of 7 m each.

The most visible part of each antenna is the dish, a large reflecting surface. Most of ALMA’s dishes have a diameter of 12 m. Each dish plays the same role as the mirror of an optical telescope: it collects radiation coming from distant astronomical objects, and focuses it into a detector that measures the radiation. The difference between the two types of telescopes is the wavelength of the radiation detected. Visible light, captured by optical telescopes, is just a small part of the spectrum of electromagnetic radiation, with wavelengths between roughly 380 and 750 nm. ALMA, in contrast, will probe the sky for radiation at longer wavelengths from a few hundred µm to about 1 mm (about one thousand times longer than visible light). This is known, perhaps unsurprisingly, as mm and sub-mm radiation, and lies at the very short-wavelength end of radio waves.

This longer wavelength range is the reason, why ALMA’s dishes are not mirrors, but have a surface of metallic panels. The reflecting surfaces of any telescope must be virtually perfect: if they have any defects that are larger than a few percent of the wavelength to be detected, the telescope won’t produce accurate measurements. The longer wavelengths that ALMA’s antennas detect mean that although the surfaces are accurate to within 25 µm — much less than the thickness of a single sheet of paper, the dishes do not need the mirror finish used for visible-light telescopes. So although ALMA’s dishes look like giant metallic satellite dishes, to a submillimeter-wavelength photon (light-particle), they are almost perfectly smooth reflecting surfaces, focusing the photons with great precision.

Not only are the dish surfaces carefully controlled, but the antennas can be steered very precisely and pointed to an angular accuracy of 0.6 arcseconds (one arcsecond is 1/3600 of a degree). This is accurate enough to pick out a golf ball at a distance of 15 km.

ALMA will combine the signals from its array of antennas as an interferometer — acting like a single giant telescope as large as the whole array. Thanks to the two antenna transporter vehicles, astronomers will be able to reposition the antennas according to the kind of observations needed. So, unlike a telescope that is constructed and remains in one place, the antennas are robust enough to be picked up and moved between concrete foundation pads without this affecting their precision engineering.

In addition, the antennas achieve all this without the protection of a telescope dome or enclosure. The dishes are exposed to the harsh environmental conditions of the high altitude Chajnantor plateau, with strong winds, intense sunlight, and temperatures between ±20 ºC. Despite Chajnantor being in one of the driest regions on the planet, there is even sometimes snow here, but ALMA’s antennas are designed to survive all these hardships.

The production of the antennas is being shared between the ALMA partners. ESO has ordered twentyfive 12 m antennas, with an option for an additional seven, from the AEM Consortium (Alcatel Alenia Space France, Alcatel Alenia Space Italy, European Industrial Engineering S.r.L., MT Aerospace). The North American partners have placed an order of the same size with Vertex RSI, while the four 12 m and twelve 7 m antennas comprising ALMA’s ACA (Atacama Compact Array) have been ordered by NAOJ from MELCO (Mitsubishi Electric Corporation).

Apart from the obvious difference in size between the 12-meter and 7-meter antennas, careful observers will spot subtle differences in the antenna design from each partner. However, all the antennas are designed to meet the stringent technical specifications, and work together smoothly as parts of the whole. These state-of-the-art dishes, combined in a single revolutionary telescope, reflect the cooperative nature of the global ALMA project.

ALMA Front End Integration Centers: A construction project like ALMA, involving several partners in four different continents, requires consensus on several organizational and managerial decisions concerning the actual execution of certain construction activities. Several different scenarios for assembling and integrating the Front End components were extensively studied. This study revealed that the best solution was a “parallel approach”, installing half of the Front End in Europe and the other half in North America with identical and parallel procedures. This scenario was preferred in view of logistics, organization and program risks. Mainly based on considerations of risk mitigation, the parallel FEIC (Front End Integration Centers) was selected. The European FEIC is located at Rutherford Appleton Laboratory (UK) and the North American FEIC at NRAO. A third FEIC is installed in Taiwan to carry out the integration of Front End assemblies required for the antennas supplied by NAOJ.

A world-class observatory site in the desert: 18)

The ALMA Observatory is operated at two distinct sites, far away from comfortable living conditions of modern civilization. The ALMA OSF is the base camp for the every-day, routine operation of the observatory. It is located at an altitude of about 2900 m, quite high compared to standard living conditions, but still quite acceptable for scientific projects in astronomy of similar scope. However, the OSF will not only serve as the location for operating the Joint ALMA Observatory, it is also the AIV (Assembly, Integration and Verification) station for all the high technology equipment before being moved to the AOS (Array Operations Site), located at 5000 m altitude. Antenna assembly is done at the OSF site at three separate areas, one each for the antennas provided by North America (VERTEX), Japan (MELCO), and Europe (AEM Consortium).

The OSF is also the center for activities associated with commissioning and science verification as well as Early Science operation. During the operations phase of the observatory it is the workplace of the astronomers and of the teams responsible for maintaining proper functioning of all the telescopes.

The construction of the OSF and AOS sites and their access required substantial efforts of the ALMA project. Obviously, there was no access to these two remote locations (Figure 9). The OSF site, located at 2900 m altitude, is about 15 km away from the closest public road, the Chilean highway No. 23. The AOS is another 28 km away from the OSF site. Thus, one of the first projects to be accomplished by ALMA was to construct an access road not only to the OSF but also to the AOS road, 43 km in length, not only at high altitudes, but also with sufficient width to regularly transport a large number of large radio telescopes with a diameter of 12 m.

The geographical location of ALMA (at Altiplano de Chajnantor) is latitude: -23.029° ; longitude: -67.755°

Front End System

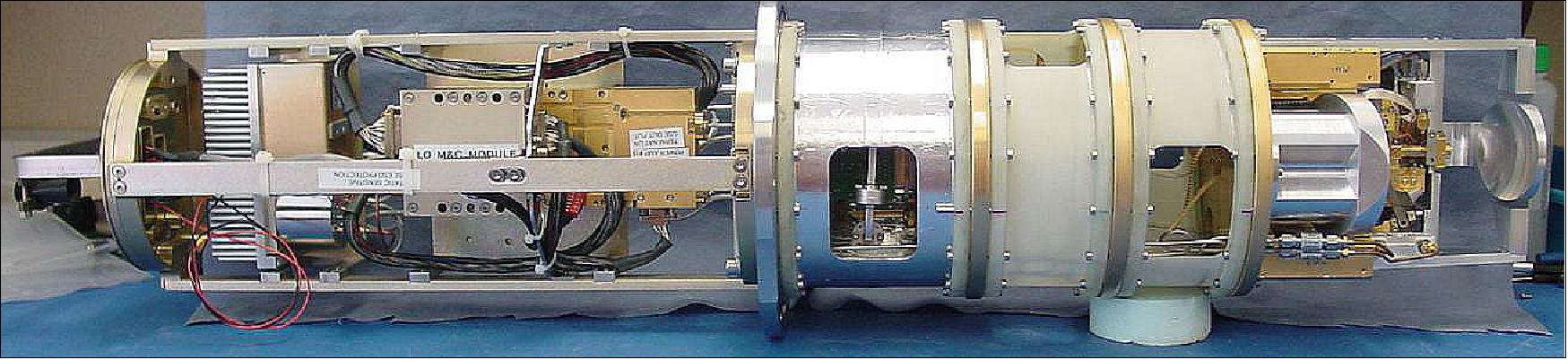

The ALMA Front End system is the first element in a complex chain of signal receiving, conversion, processing and recording. The Front End is designed to receive signals of ten different frequency bands. 19)

The ALMA Front End is far superior to any existing systems. Indeed, spin offs of the ALMA prototypes are leading to improved sensitivities in existing millimeter and submillimeter observatories around the world. The Front End units are comprised of numerous elements, produced at different locations in Europe, North America, East Asia and Chile.

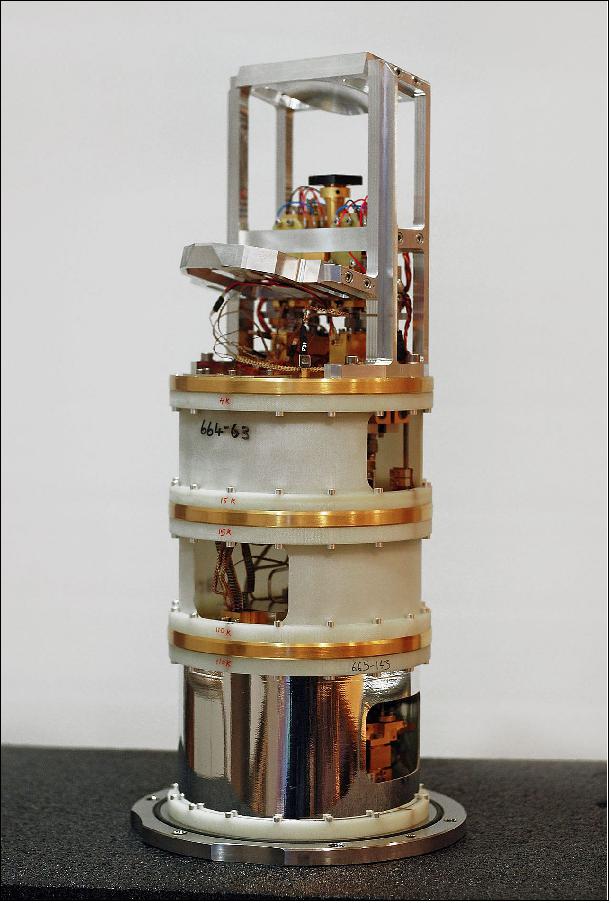

ALMA Cryostats: The largest single element of the Front End system is the cryostat (vacuum vessel) with the cryo-cooler attached. The cryostats will house the receivers, which are assembled in cartridges and can relatively easily be installed or replaced. The corresponding warm optics, windows and infrared filters were delivered by the IRAM (Institut de Radio Astronomie Millimétrique) of France. The operating temperature of the cryostats will be as low as 4 K (equivalent to -269ºC).

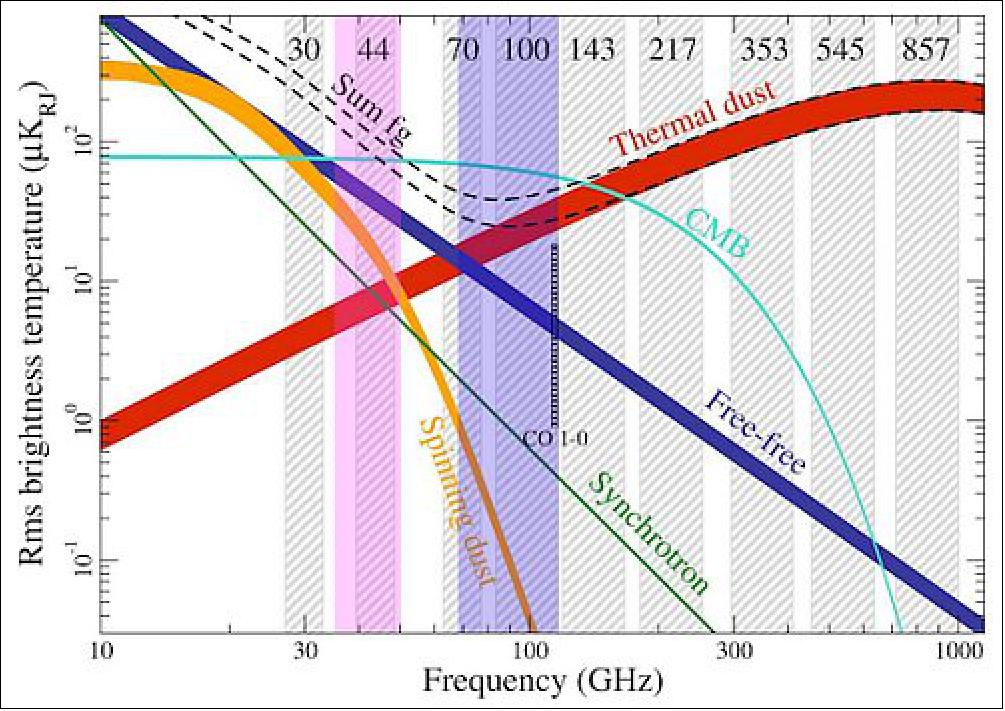

ALMA Receiver Bands: In the initial phase of operations, the antennas will be equipped with at least four receiver bands: Band 3 (3 mm), Band 6 (1 mm), Band 7 (0.85 mm), Band 9 (0.45 mm). It is planned to equip the antennas with the missing bands at a later stage of ALMA operations. The development programs were successful, as the requirements could be met – and sometimes the performance is even better than defined in the specifications.

ALMA band | Frequency range (GHz) | Receiver noise (K) over 80% of the RF band | Temperature (K) at any RF frequency | To be produced by | Receiver technology |

1 | 31 - 45 | 17 | 26 | TBD (To be decided) | HEMT |

2 | 67 - 90 | 30 | 47 | TBD | HEMT |

3 | 84 - 116 | 37 | 60 | HIA | SIS |

4 | 125 - 163 | 51 | 82 | NAOJ | SIS |

5 | 162 - 211 | 65 | 105 | OSO | SIS |

6 | 211 - 275 | 83 | 136 | NRAO | SIS |

7 | 275 - 373 | 147 | 219 | IRAM | SIS |

8 | 385 -500 | 196 | 292 | NAOJ | SIS |

9 | 602 - 720 | 175 | 261 | NOVA | SIS |

10 | 787 - 900 | 230 | 344 | NAOJ | SIS |

IRAM (Institut de Radio Astronomie Millimétrique), Grenoble, France | |||||

Modular Cryogenic Receiver Concept. The complete front end unit will have a diameter of 1 m, be about 1m high and have a mass of about 750 kg. The cryostat will be cooled down to ~4 K by a 3-stage commercial closed-cycle cryocooler based on the Gifford – McMahon cooling cycle. The individual frequency bands are implemented in the form of modular cartridges that will be inserted in a large common cryostat. This cartridge concept allows for a great flexibility in construction and operation of the array. Figure 10 shows an example of such a receiver cartridge. Another advantage of the cartridge layout with well-defined interfaces is the fact that different cartridges can be developed and built by different groups within the ALMA Project with a large degree of independence but without the risk of incompatibility between them. 20)

Band 5 — July 17, 2015: After more than five years of development and construction, ALMA successfully opened its eyes on another frequency range after obtaining the first fringes with a Band 5 receiver, specifically designed to detect water in the local Universe. Band 5 will also open up the possibility of studying complex molecules in star-forming regions and protoplanetary discs, and detecting molecules and atoms in galaxies in the early Universe, looking back about 13 billion years (Ref. 11).

“Band 5 will open up new possibilities to explore the Universe and bring new discoveries,” explains ESO’s Gianni Marconi, who is responsible for the integration of Band 5. “The frequency range of this receiver includes an emission line of water that ALMA will be able to study in nearby regions of star formation. The study of water is, of course, of intense interest because of its role in the origin of life.” With Band 5, ALMA will also be able to probe the emission from ionized carbon from objects seen soon after the Big Bang, opening up the possibility of probing the earliest epoch of galaxy formation. “This band will also enable astronomers to study young galaxies in the early Universe about 500 million years after the Big Bang,” added Gianni Marconi.

The Band 5 receivers were originally designed and prototyped by Onsala Space Observatory's Group for Advanced Receiver Development (GARD) at Chalmers University of Technology in Sweden, in collaboration with the Rutherford Appleton Laboratory, UK, and ESO, under the European Commission supported Framework Program FP6 (ALMA Enhancement). After having successfully tested the prototypes, the first production-type receivers were built and delivered to ALMA by a consortium of NOVA and GARD in the first half of 2015. Two receivers were used for the first light. The remainder of the 73 receivers ordered, including spares, will be delivered between now and 2017.

Back End and Correlator

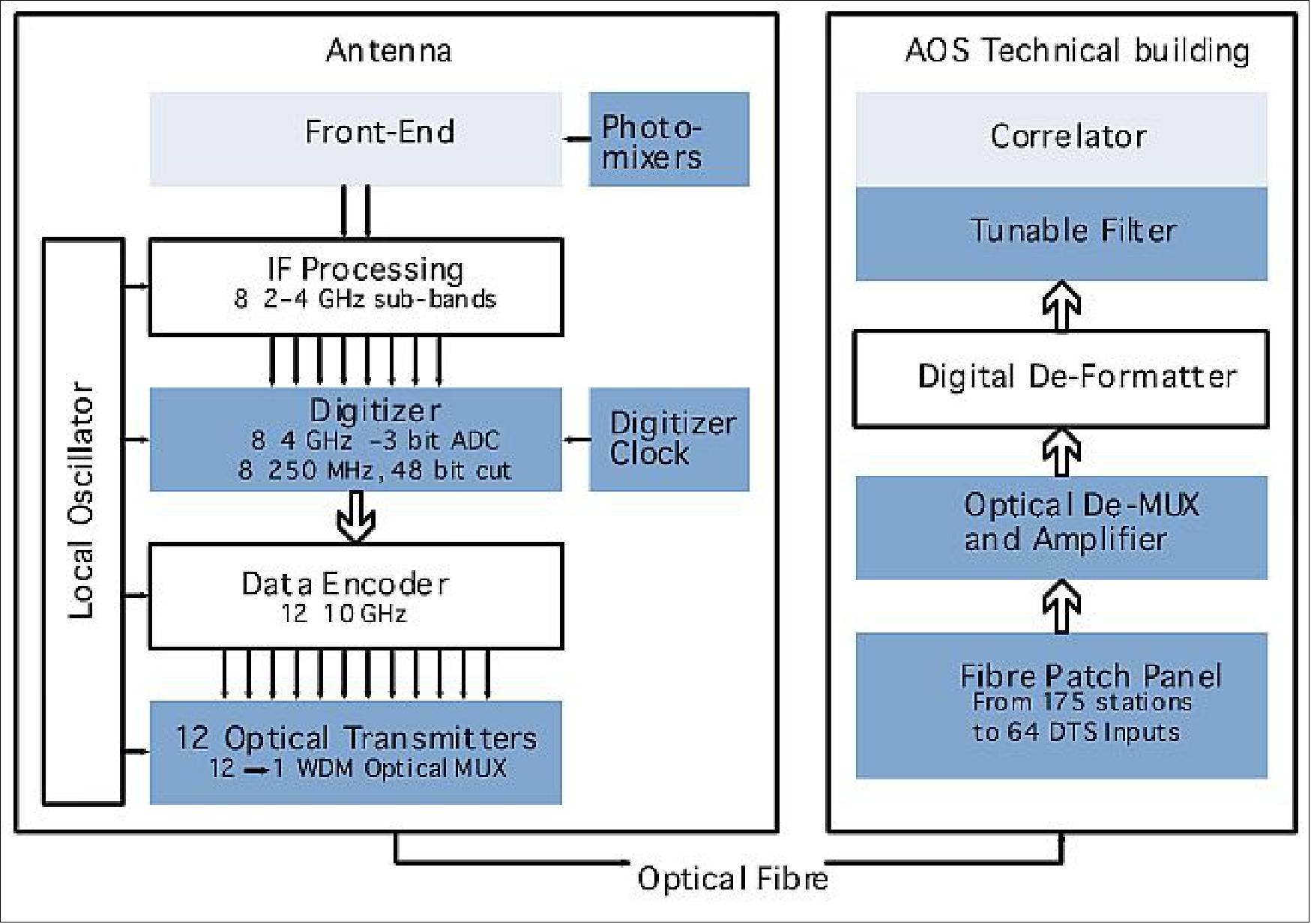

The ALMA Back End systems deliver signals generated by Front End units installed in each antenna to the Correlator installed in the AOS (Array Operations Site) Technical Building, located at an altitude of 5,000 m. Signal processing and data transfer is schematically shown in Figure 13. Analog data, produced by the Front End electronics, is processed and digitized before entering into the data encoder, followed by the optical transmitter units and multiplexers. All these elements are installed in the receiver cabins of each antenna. Optical signals are then transmitted by fibers to the AOS Technical Building. The total distance is, in one antenna configuration, about 15 km. At the Technical Building the incoming optical signals are de-multiplexed and de-formatted before entering the Correlator. 21) 22) 23)

ALMA main array Correlator: The ALMA main array Correlator, to be installed in the AOS Technical Building, is the last component in the receiving end of the data transmission. It is a very large data processing system, composed of four quadrants, each of which can process data coming from up to 504 pairs of antennas. The complete correlator will have 2912 printed circuit boards, 5200 interface cables, and more than 20 million solder points. Integral parts of the Correlator are TFB (Tunable Filter Bank) cards. The layout is such that four TFB cards are needed for the data coming from a single antenna. The TFB cards have been developed and optimized by the University of Bordeaux over the last few years.

ACA (Atacama Compact Array) Correlator: The ACA Correlator is designed to process the signals detected by the Atacama Compact Array (ACA). This correlator consists of 52 modules connected with each other through optical-fiber cables. All the modules are installed in 8 racks in the AOS Technical Building. The power spectra issued from the correlation are transferred to the ACA data processing computers.

• May 15, 2020: The contract has been signed for the production of the final set of receivers to be installed on the Atacama Large Millimeter/submillimeter Array (ALMA). Of the originally foreseen ten receiver bands, eight have already been installed, and the ninth, Band 1, is currently in production in East-Asia. Now, contracts have been signed to start the production of the final band in the original ALMA definition — Band 2, led by ESO. Exceeding the originally defined frequency range for this Band (69-90 GHz), the proposed receiver will operate at the full 67-116 GHz frequency window. The hugely successful Band 3 receiver has already opened up the 84-116 GHz frequency range years ago, but the new Band 2 will allow for observations across the entire 67-116 GHz atmospheric window using a single receiver. The project will involve multiple international partners as detailed below. 24)

Following successful tests of a prototype Band 2 receiver (Yagoubov et al. 2020, A&A 634, A46), the ALMA board has approved the pre-production of a series of six cartridges, with the goal of eventually moving into the production of the full set, one for each of the ALMA antennas. This will depend on the verification of the performance and series production readiness based on the pre-production receiver cartridges.

The 67-116 GHz atmospheric window is rich in strong molecular lines with less crowding than other atmospheric windows. Due to the relatively low excitation energies, these lines are exceptionally suited for studying the dense molecular gas and early phases of star formation. Furthermore, the window is rich in complex organic molecules (COMs), tying in directly with the new fundamental science drivers defined in the ALMA 2030 Development Roadmap. Band 2 will also fill a gap in ALMA's ability to observe the molecular reservoir in redshifted galaxies. Finally, Band 2 continuum measurements have the lowest intrinsic background, as thermal dust emission, CMB emission, free-free emission and synchrotron emission conspire to form a local emission minimum in frequency space.

The production of the Band 2 receiver cartridges will be undertaken by a consortium comprising the Netherlands Research School for Astronomy (NOVA), Chalmers University, Gothenburg, Sweden, and the Italian National Institute for Astrophysics (INAF). The National Astronomical Observatory of Japan (NAOJ) will contribute to the production and testing of receiver optics as an East Asia contribution to the ALMA Development Program. The National Radio Astronomy Observatory (NRAO) and the University of Chile have been involved in the development and production of some components of the receivers, which will be sent to ESO for testing and integration.

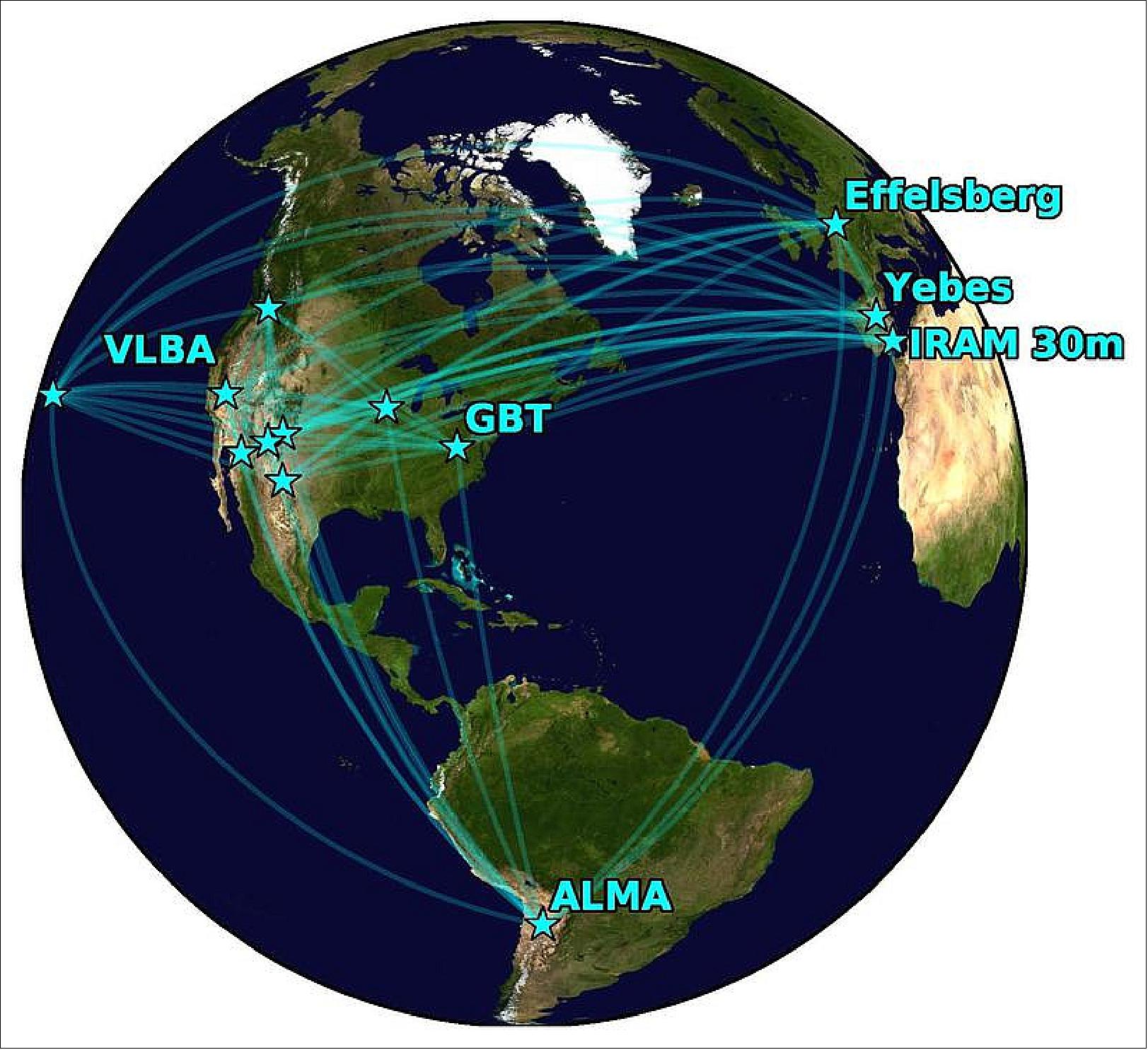

Links to Other Observatories to Create an Earth-size Telescope

November 2015: ALMA continues to expand its power and capabilities by linking with other millimeter-wavelength telescopes in Europe and North American in a series of VLBI (Very Long Baseline Interferometry) observations. In VLBI, data from two or more telescopes are combined to form a single virtual telescope that spans the geographic distance between them. The most recent of these experiments with ALMA formed an Earth-size telescope with extraordinarily fine resolution. 25)

These experiments are an essential step in including ALMA in the EHT (Event Horizon Telescope), a global network of millimeter-wavelength telescopes that will have the power to study the supermassive black hole at the center of the Milky Way in unprecedented detail.

Before ALMA could participate in VLBI observations, it first had to be upgraded adding a new capability known as a phased array. This new version of ALMA allows its 66 antennas to function as a single radio dish 85 m in diameter, which then becomes one element in a much larger VLBI telescope.

• The first test of ALMA’s VLBI capabilities occurred on 13 January 2015, when ALMA successfully linked with the APEX (Atacama Pathfinder Experiment Telescope), which is about two kilometers from the center of the ALMA array.

• On 30 March 2015, ALMA reached out much further by linking with IRAM (Institut de Radioastronomie Millimetrique), the 30 m radio telescope in the Sierra Nevada of southern Spain. Together they simultaneously observed the bright quasar 3C 273. Data from this observation were combined into a single observation with a resolution of 34 µarcsec (1 microarcsecond = 2.8º x 10-10). This is equivalent to distinguish an object of less than 10 cm on the Moon, seen from Earth. - The March observations were made during an observing campaign of the EHT at a wavelength of 1.3 mm.

• The most recent VLBI observing run was performed on 1–3 August 2015 with six of the VLBA (Very Long Baseline Array) antennas of NRAO (National Radio Astronomy Observatory). This combined instrument formed a virtual Earth-size telescope and observed the quasar 3C 454.3, which is one of the brightest radio beacons on the sky, despite lying at a distance of 7.8 billion light-years. These data were first processed at NRAO and MIT-Haystack in the United States and further post-processing analysis is being performed at the MPIfR (Max Planck Institute for Radio Astronomy) in Bonn, Germany.

- The VLBA is an array of 10 antennas spread across the United States from Hawaii to St. Croix. For this observation, six antennas were used: North Liberty, IA; Fort Davis, TX; Los Alamos, NM; Owens Valley, CA; Brewster, WA; and Mauna Kea, HI. The observing wavelength was 3 mm.

• The new observations are a further step towards global interferometric observations with ALMA in the framework of the Global mm-VLBI Array and the EHT (Event Horizon Telescope), with ALMA as the largest and the most sensitive element. The addition of ALMA to millimeter VLBI will boost the imaging sensitivity and capabilities of the existing VLBI arrays by an order of magnitude.

Enhancing ALMA’s Future Observing Capabilities

• June 2021: With each observing cycle at the ALMA (Atacama Large Millimeter/submillimeter Array) new features and observing modes are offered. Here we provide some background about how these new capabilities are tested and then made available to ALMA users. These activities help to drive the cutting-edge science conducted with ALMA and to maintain ALMA’s position as the foremost interferometric array operating at millimeter and submillimeter wavelengths. We focus in particular on opening up high-frequency observing using ALMA’s longest baselines, which offers the highest possible angular resolution. 26)

Extension and Optimization of New Capabilities

- The global effort of adding new capabilities to ALMA is referred to as Extension and Optimization of Capabilities (EOC). EOC was the natural progression after moving away from initial tests when ALMA was commissioned. During the final years of construction and during Cycle 0 operations, almost ten years ago, the development of new modes was called Commissioning and Scientific Verification (CSV). CSV was conducted to ensure that the capabilities offered were fully operational and valid. Following this, with ALMA as a fully operational telescope, testing as part of EOC activities has continued as an ALMA-wide effort encompassing all partners1: the Joint ALMA Observatory (JAO) in Chile and the ALMA Regional Centres (ARCs) in East Asia, North America and Europe. In Europe there are also contributions from the ARC network (see Hatziminaoglou et al., 2015). The entire EOC effort, including all coordination, planning and the intricate steps involved, is led by the JAO (see Takahashi et al., 2021).

- In this article we provide an overview of EOC, and what features might be expected in the coming cycles, with a specific focus on pushing ALMA to achieve the highest angular resolutions possible (a study involving significant input from the European ARC). We also highlight how the ALMA community benefits from each capability potentially offered.

Process for Offering New Capabilities

- Behind the scenes, the process that makes new capabilities possible is the ObsMode process (Takahashi et al., 2021), which is led and coordinated by the JAO. The intention of the ObsMode process is to enable all observing modes that ALMA was designed to support, as well as any additional ones identified since construction began.

- Unfortunately, ALMA cannot simply test a new observing mode on the telescope and thereafter open it directly to the community. This is because all parts of the observing chain involving the so-called subsystems (Control software, Observing Tool [OT], Scheduling, Quality Assurance [QA], Pipeline, and Archive, to name just a few) must be up to the task. Before opening a new capability to the community, ALMA must be able to demonstrate the entire workflow: the correct creation of the observation files; successful, error-free observations; data reduction — first using manual scripts and thereafter with the ALMA Pipeline; and finally data and product ingestion into the ALMA Archive such that it can be delivered to any Principal Investigator (PI) and used in any future Archive mining exercises.

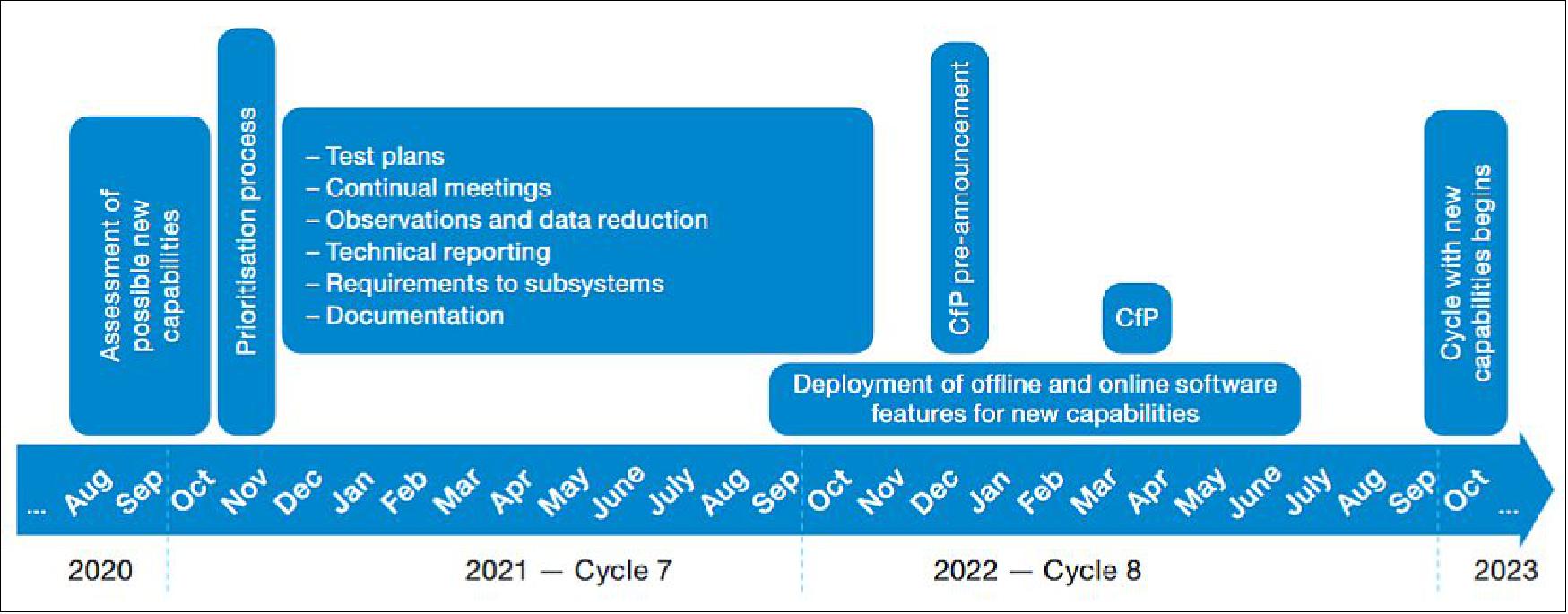

- The ObsMode process therefore follows a yearly structure and is aligned with ALMA observing cycles. For example, the majority of work in 2021 began in October 2020 and will finish in October 2021 (Figure 16). This system includes a two-year lead time, such that any capability planned for release in Cycle 9 (due to start in October 2022) must be fully tested and verified in Cycle 7a. Final tests during the first half of Cycle 8, before the Cycle 9 Call-for-Proposals (CfP) pre-announcement is made, mark the final date to confirm the readiness of a capability for scientific operations. The main considerations throughout the year include:

- Proposed capabilities and priorities: A list is drawn up of capabilities aimed at science operations two years later. Given the ten years of ALMA operations, there is a natural continuation from previous years. ALMA management, together with the science and operations teams, arrange and discuss the priorities with the ALMA Science Advisory Committee (ASAC), which confirms that these align with the community input.

Initial capability plan: Plans are made by the expert teams leading each capability. These must provide a technical summary, identify the on-sky time requirements, and detail each team member’s role. Most importantly, the plans set the criteria for declaring a particular capability as ready.

- Test Observations: EOC observations are scheduled to have a minimal impact on standard science observations, being conducted in small time windows or when science observations cannot take place. Where possible, observations use Scheduling Blocks (SBs) constructed with the OT, however some tests require custom command-line scripts to operate ALMA in a manual mode.

- Data reduction and problem reporting: Custom scripts are employed, using the Common Astronomy Software Applications package (CASA; McMullin, 2007) reduction software with extra analysis and heuristics. Extra system-level stability and data-validity checks are also made. EOC teams aim to provide QA-like reduction workflows to enable an easier transition to science operations.

- Technical readiness: In September and October the EOC teams report their findings and provide a technical report to specific expert reviewers. These reports are used for a readiness assessment to confirm whether the capability meets the initial readiness criteria.

- Subsystem impact: Requirements are created continually throughout the year for the subsystems involved. Although developments are continual, a capability can only be declared operational when all subsystems integrate the required modifications. Examples of subsystem changes are: (1) the addition of new OT features that allow SBs to be generated, and (2) modification of the QA2 process to provide the correct reduction path (see, for example, Petry et al., 2020).

- Documentation: Before the CfP is issued, ALMA provides users with a Proposer’s Guide2 and a Technical Handbook3. These documents must fully detail and explain any newly offered capabilities.

Focusing on High Frequencies and Long Baselines with Band-to-Band (B2B)

- The European ARC (ALMA Regional Centre) is particularly involved with EOC activities to offer high-frequency observations (Bands 8, 9, and 10, > 385 GHz) using the most extended array configurations (C-8, C-9 and C-10, with maximal baselines of ~ 8.5, ~ 13.9 and ~ 16.2 km, respectively). Theoretically, the highest frequencies coupled with the longest-baseline array would achieve an angular resolution of 5 milliarcseconds. This translates to sub-au scales for sources within 200 parsecs and would provide the most detailed sub-mm picture of protoplanetary discs. For extragalactic targets, parsec scales could be resolved for sources within 40 Mpc, offering unprecedented details of galactic structures.

Note: As of 19 March 2020, the previously single large ALMA file has been split into two files, to make the file handling manageable for all parties concerned, in particular for the user community.

• This article covers the ALMA project mission and its imagery in the period 2022 and 2019, in addition to some of the mission milestones.

•ALMA imagery in the period 2018-2011

Status and Selected Observation Imagery (2022-2019)

Only a selected few images can be shown here. The interested reader is referred to the ALMA Press Release site for more details. 27) 28)

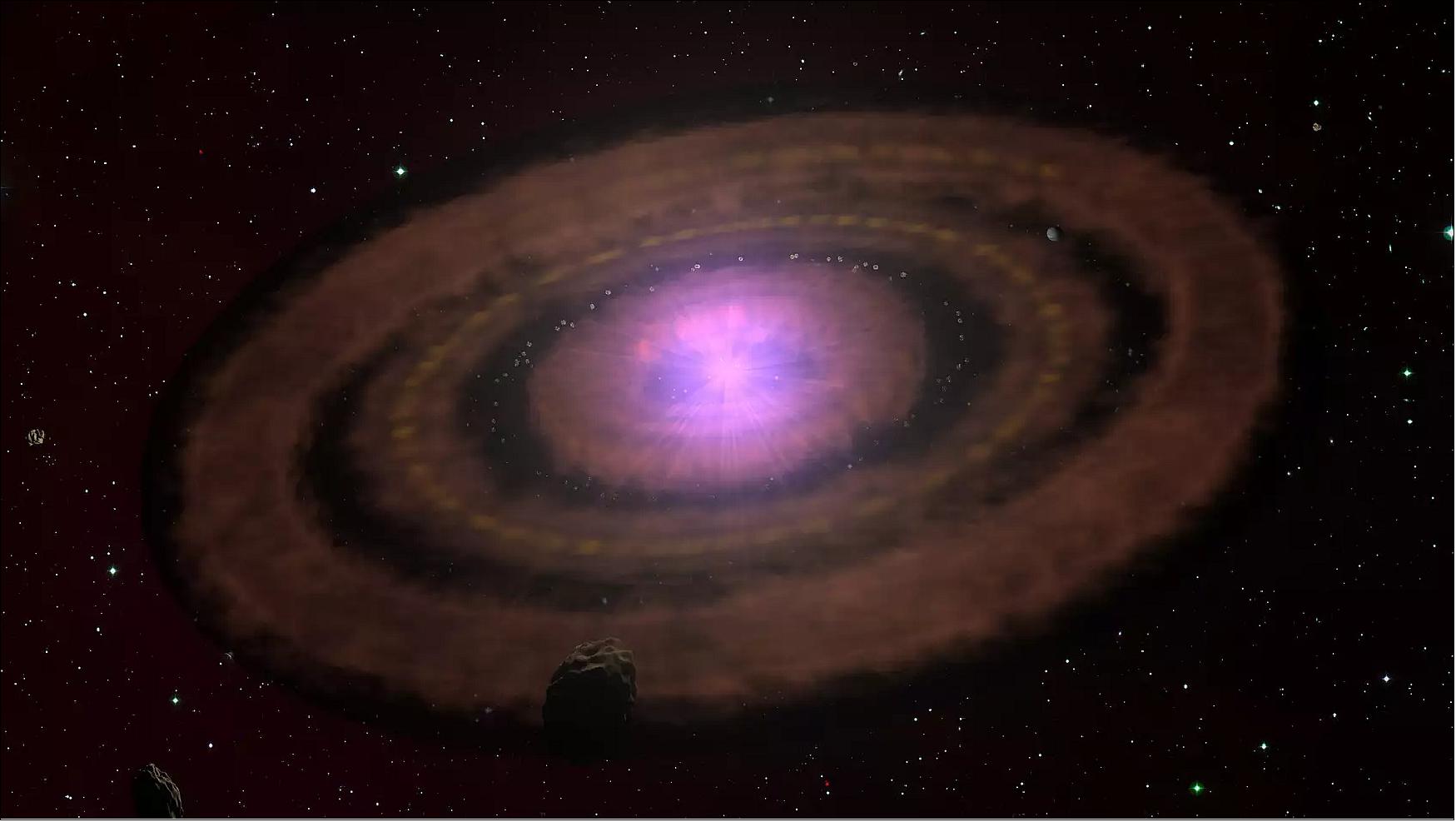

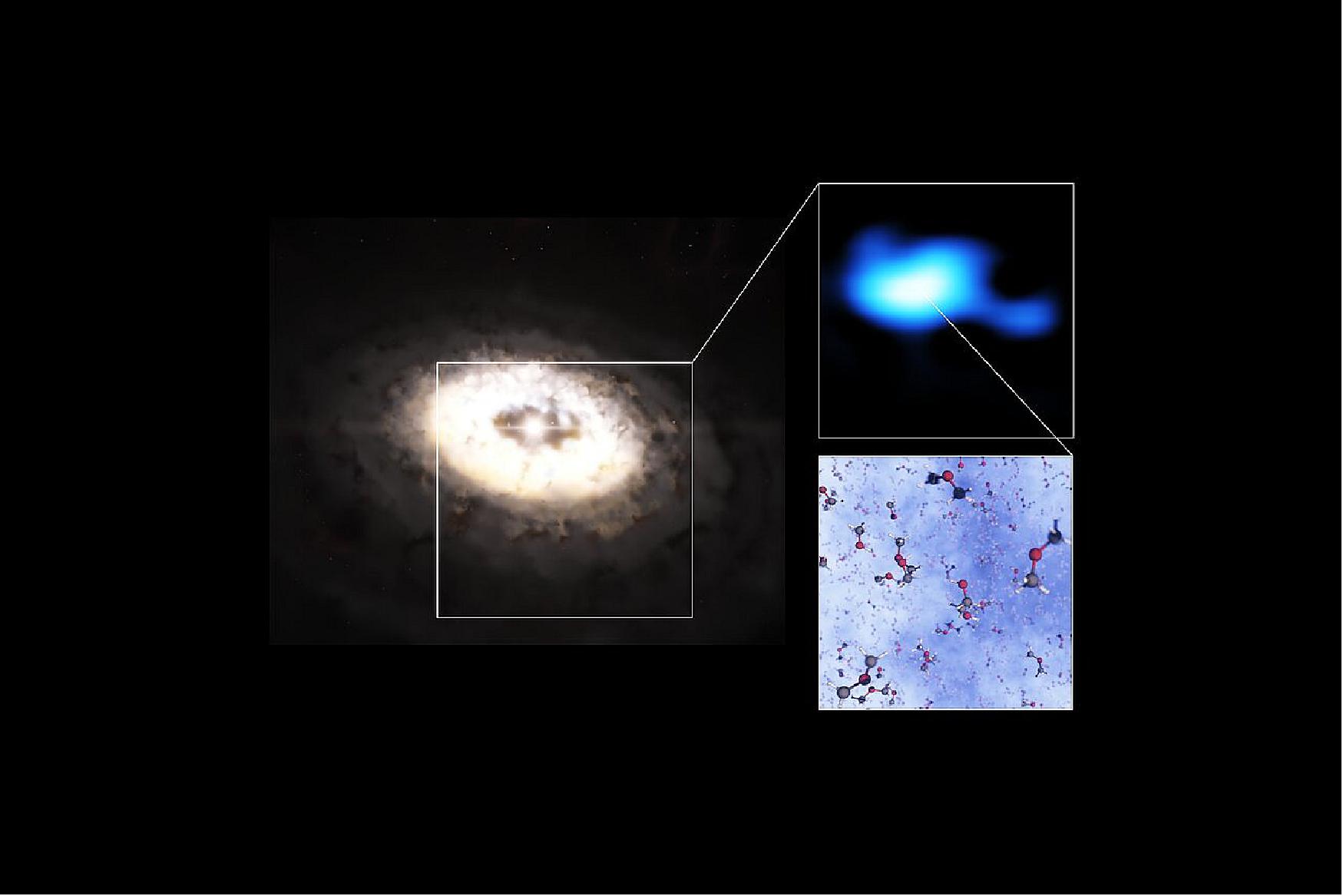

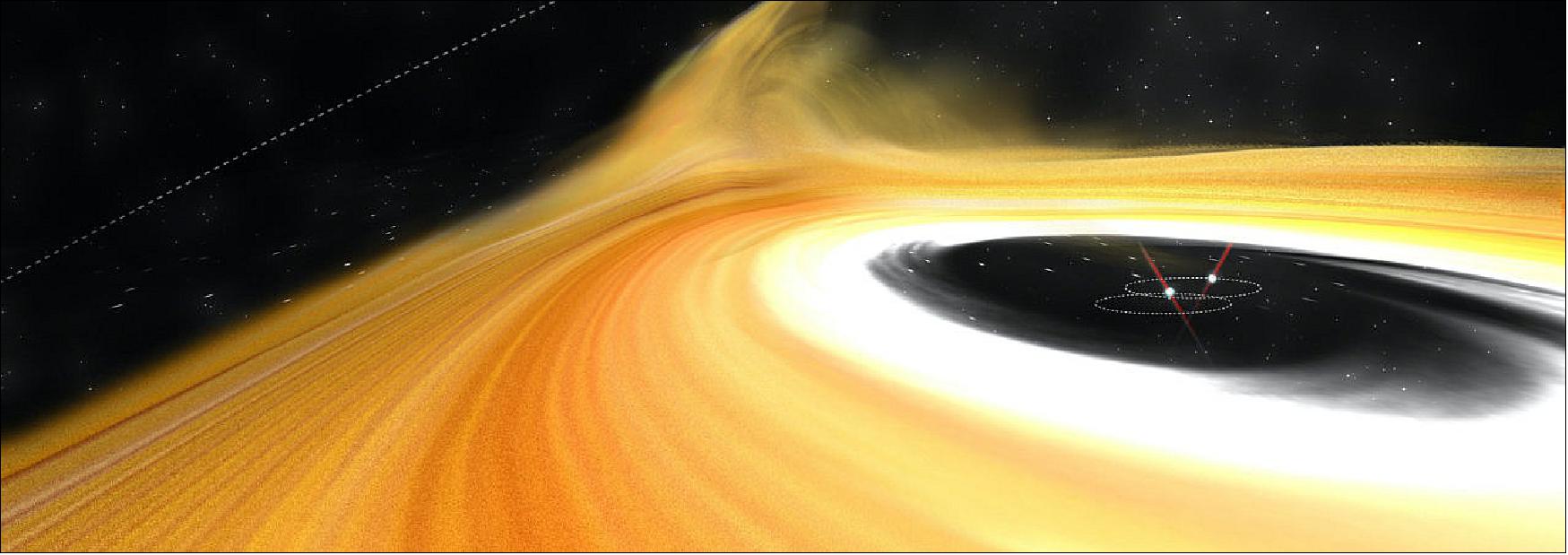

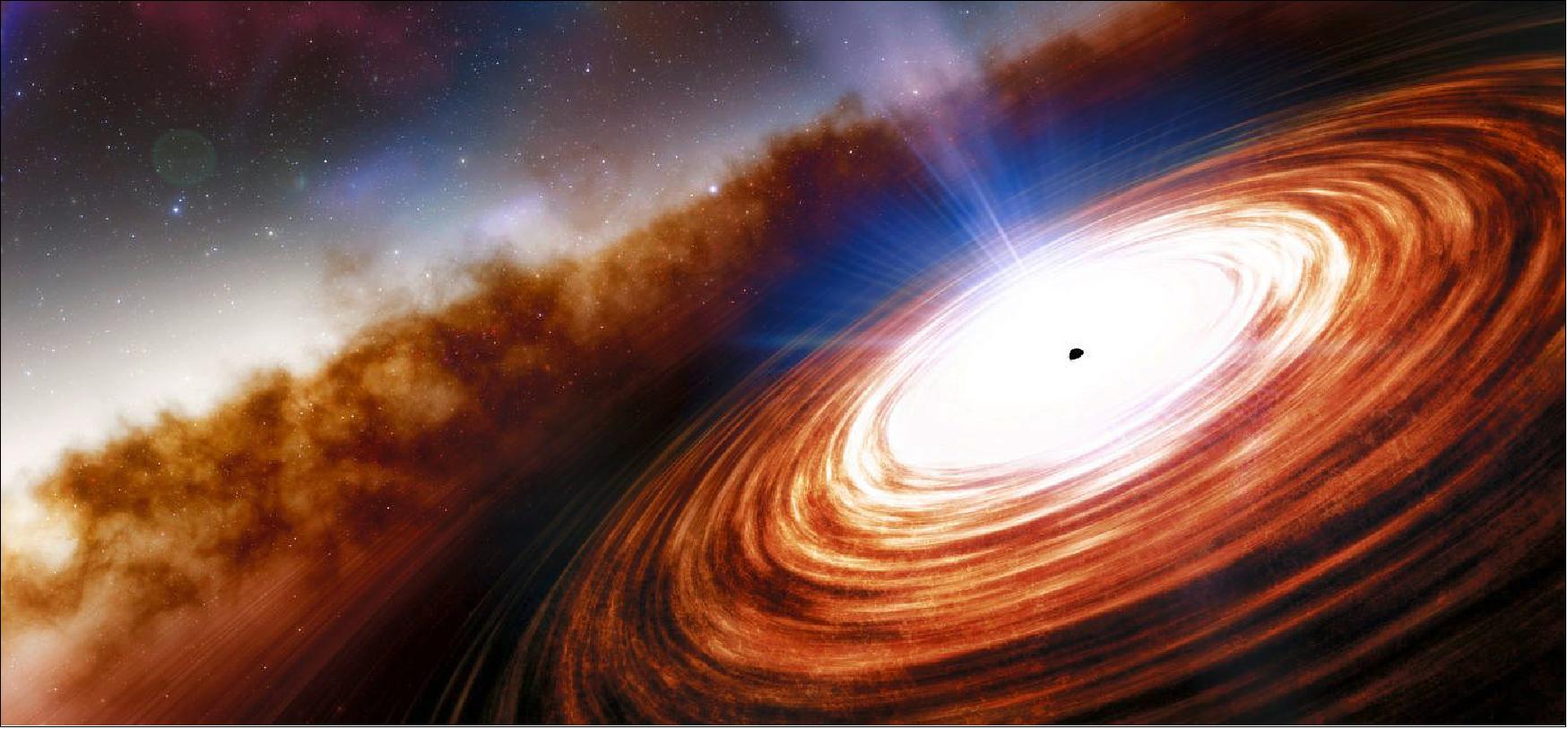

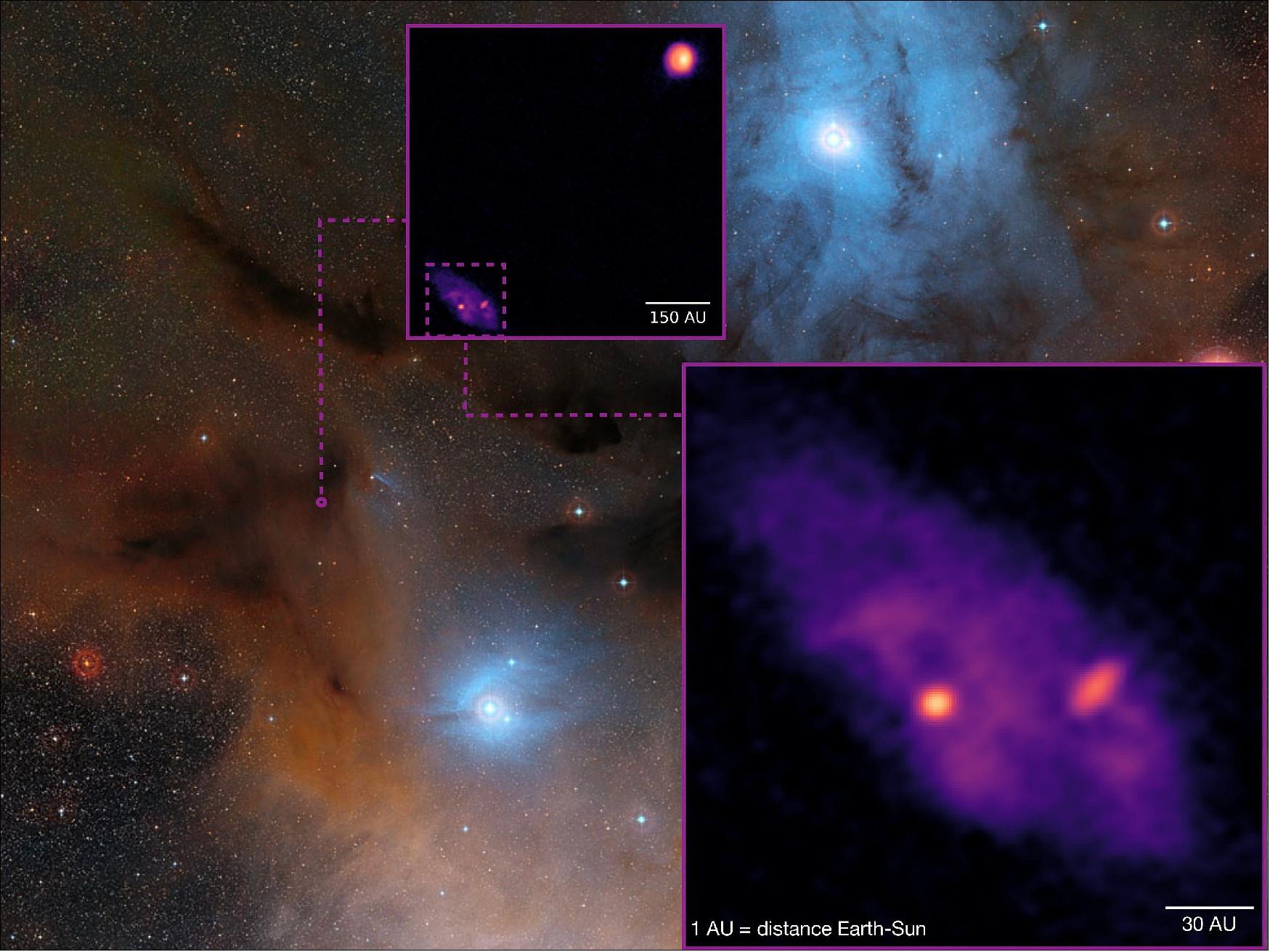

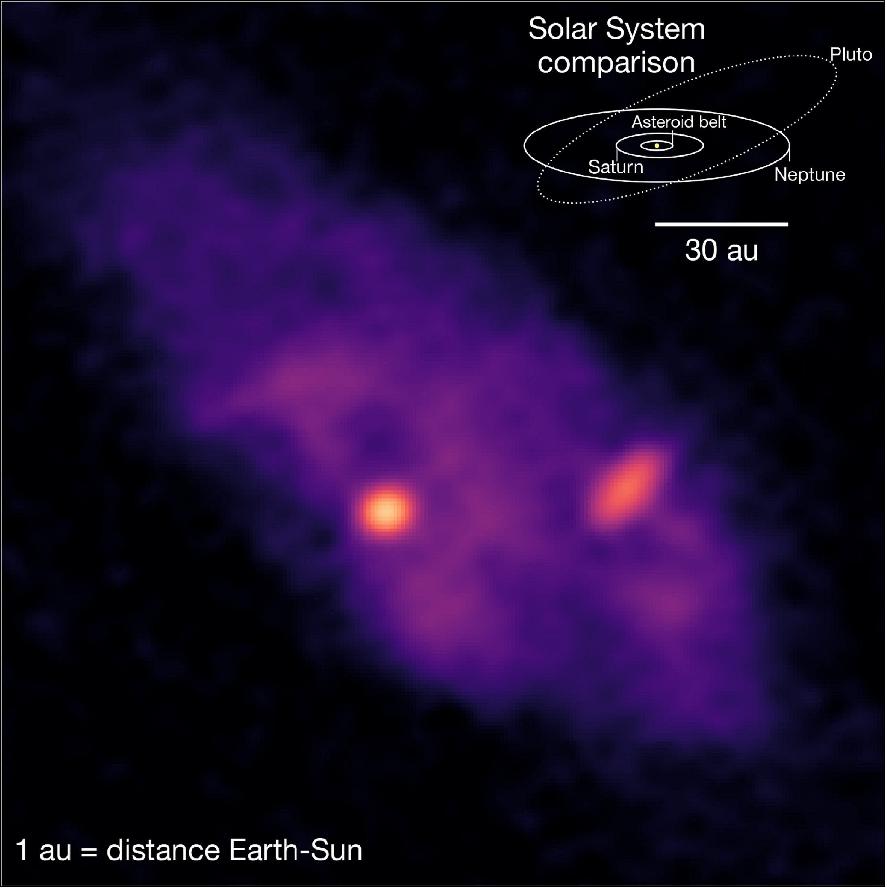

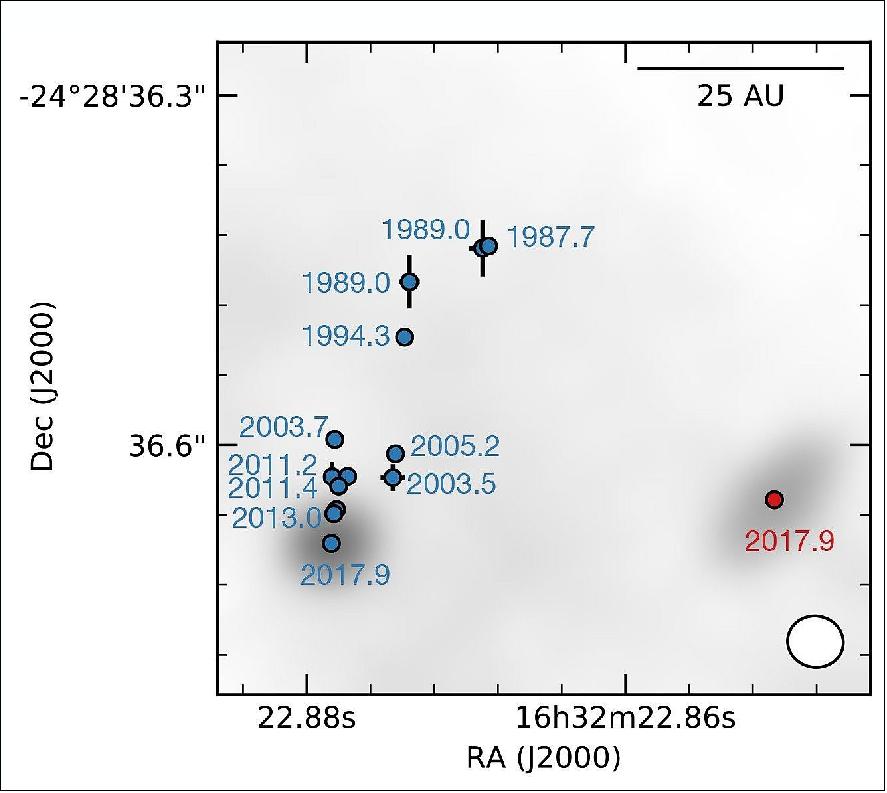

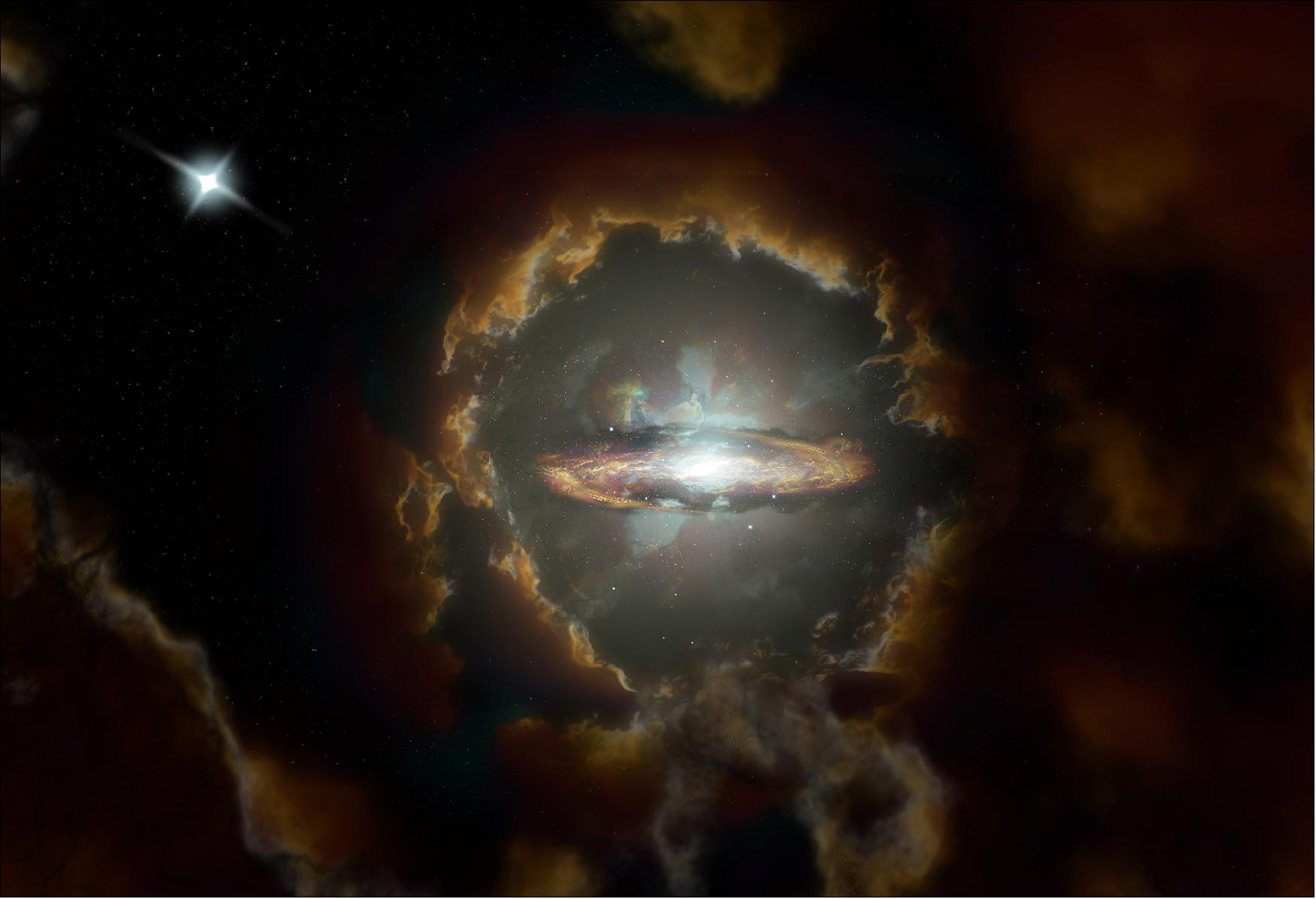

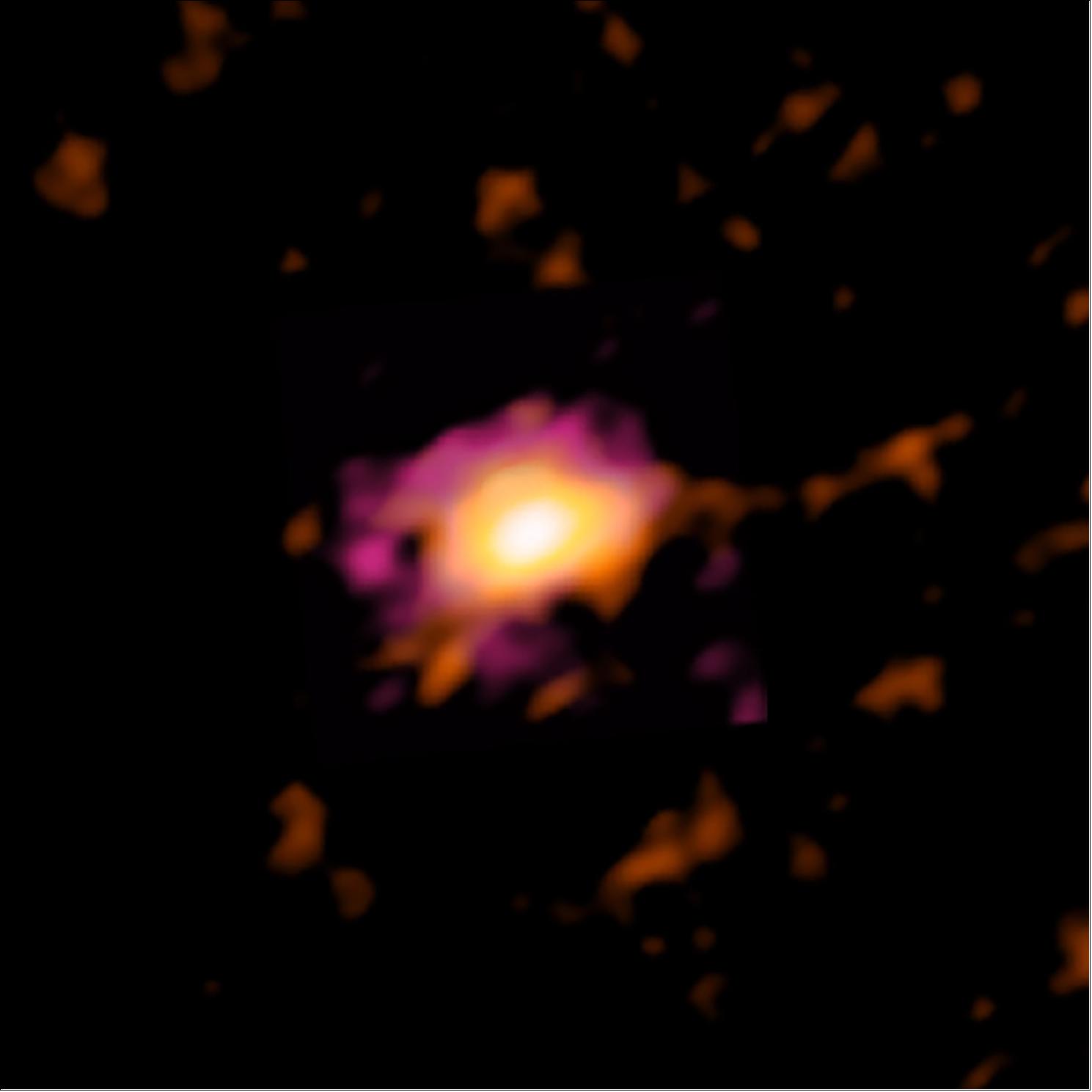

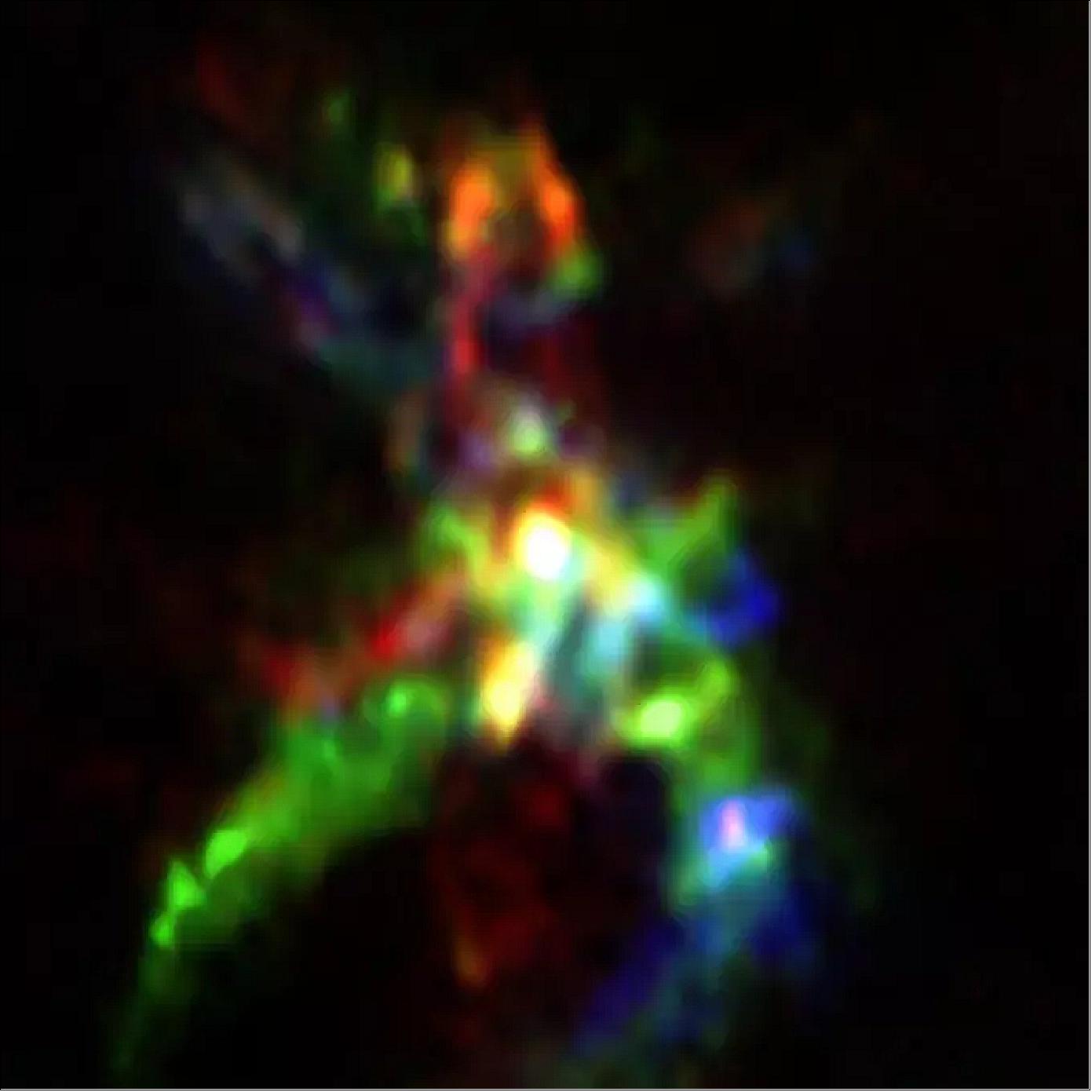

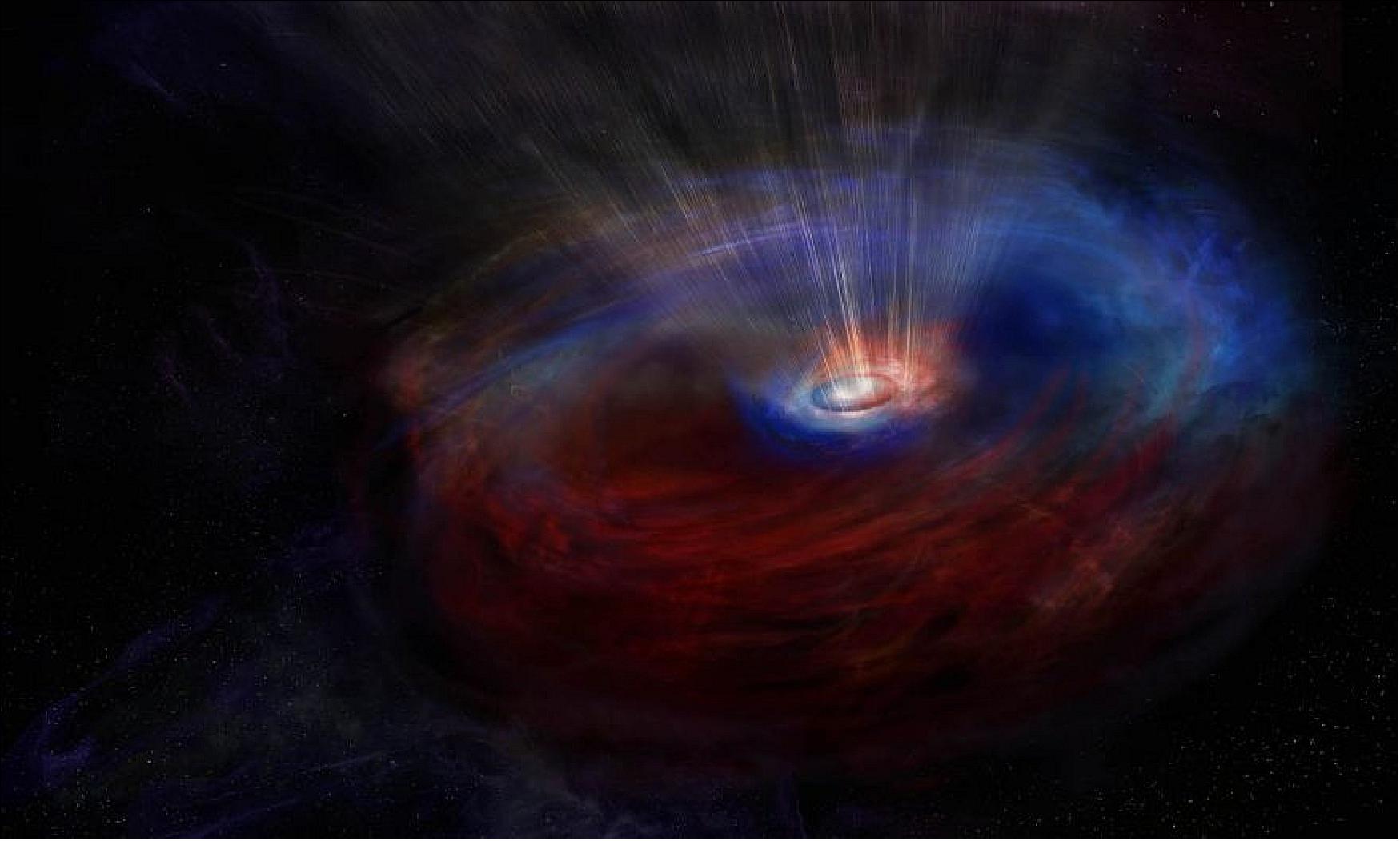

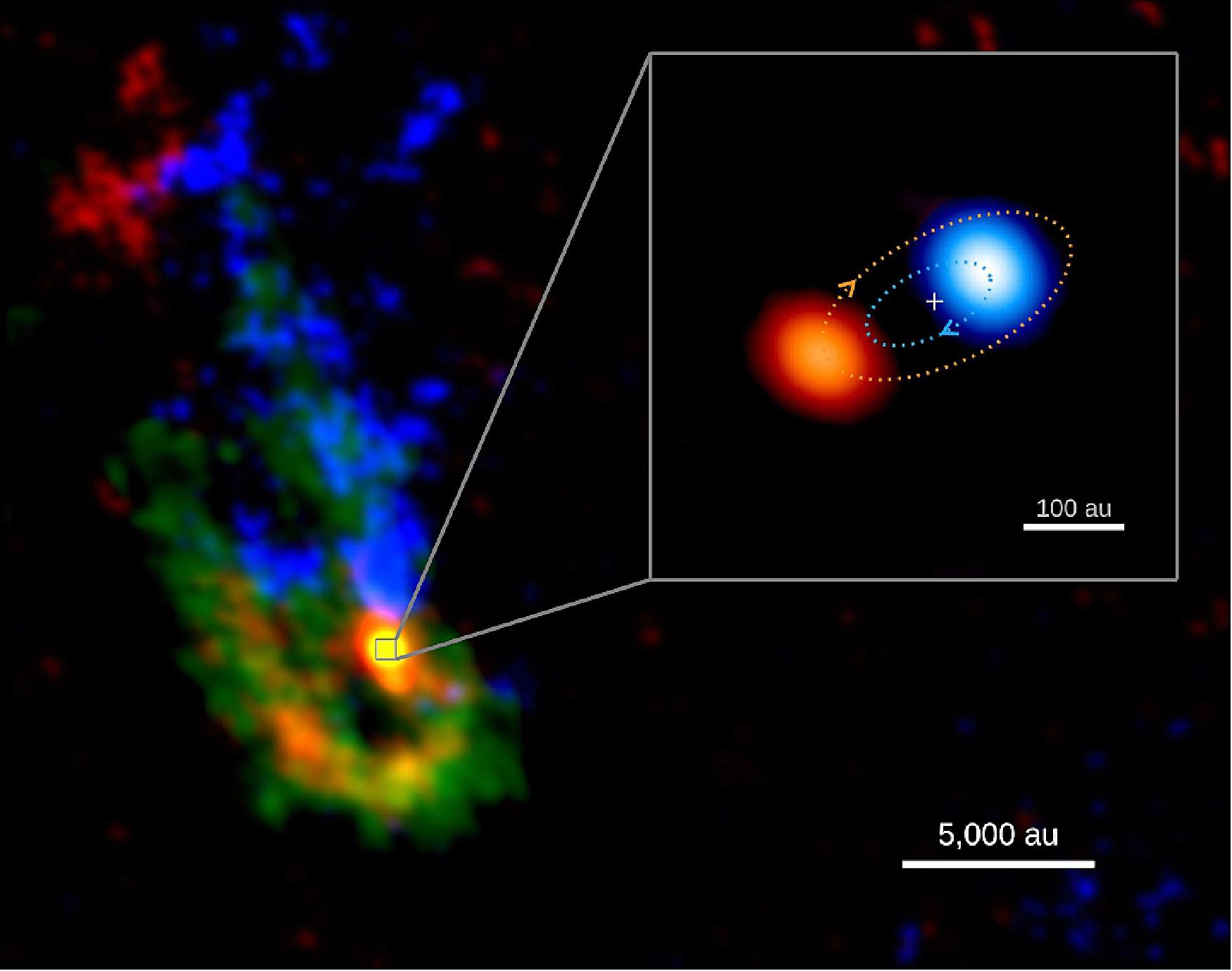

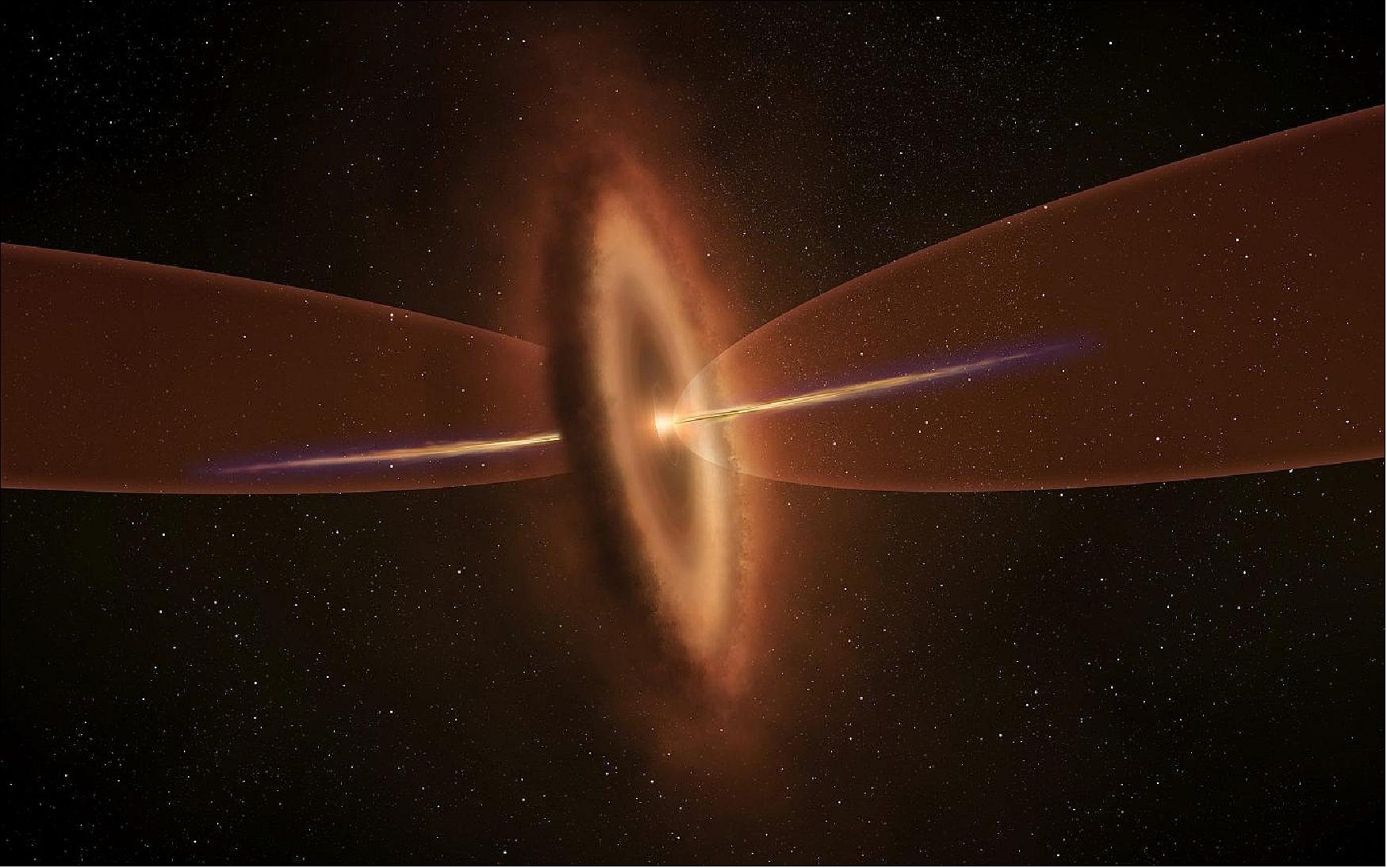

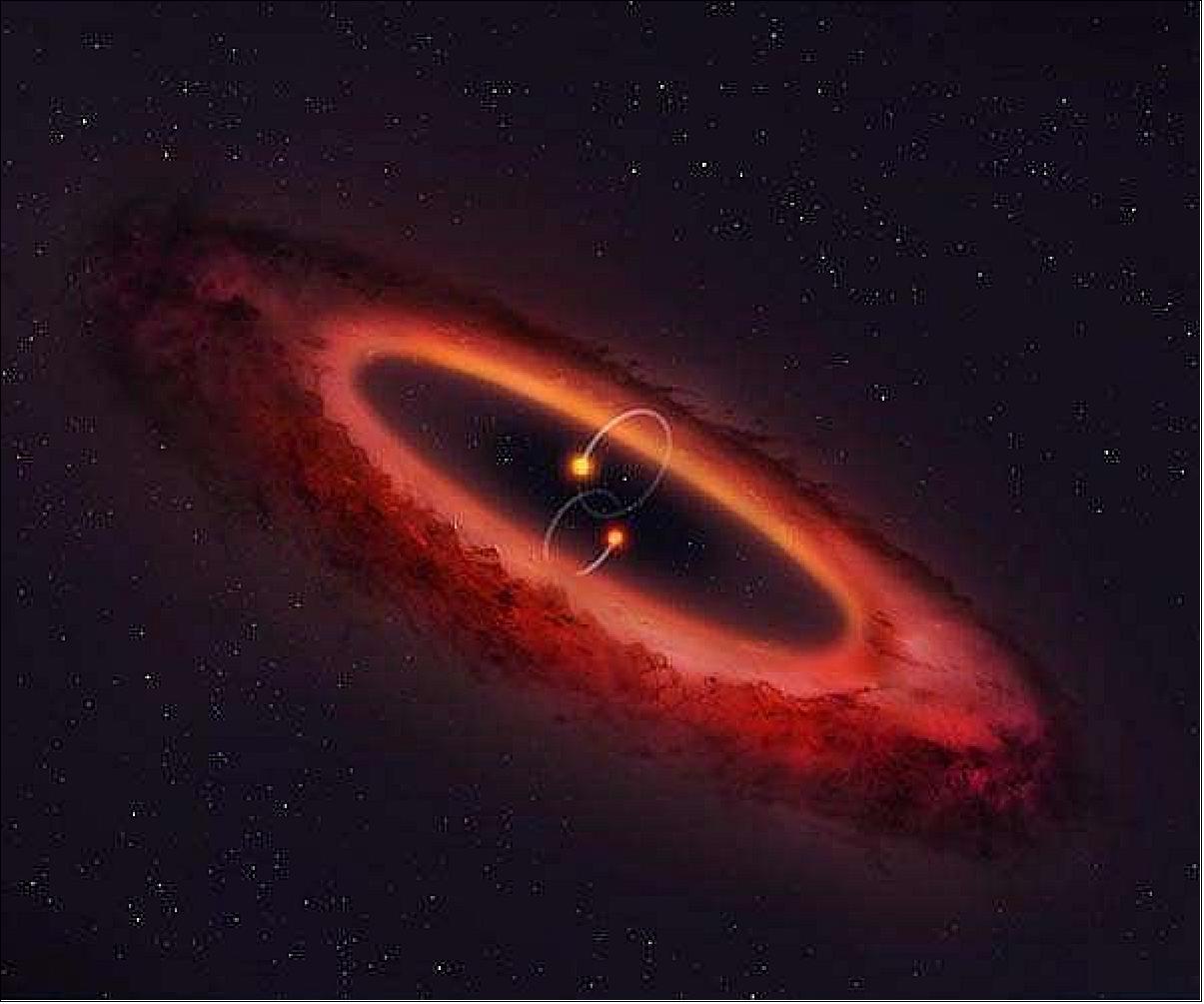

• June 18, 2022: An international research team from China, the U.S., and Germany has used high-resolution observational data from ALMA and discovered a massive accretion disk with two spiral arms surrounding a 32 solar mass protostar in the Galactic Center. This disk could be perturbed by a close encounter with a flyby object, thus leading to the formation of the spiral arms. This finding demonstrates that the formation of massive stars may be similar to that of lower-mass stars through accretion disks and flybys. 29) 30)

- Accretion disks around protostars, also known as 'protostellar disks,' are essential components in star formation because they continuously feed gas into protostars from the environment. In this sense, they are stellar cradles where stars are born and raised. Accretion disks surrounding solar-like low-mass protostars have been extensively studied in the last few decades, leading to a wealth of observational and theoretical achievements. For massive protostars, especially early O-type ones of more than 30 solar masses, it is still unclear whether and how accretion disks play a role in their formation. These massive stars are far more luminous than the Sun, with intrinsic luminosities up to several hundreds of thousands of times the solar value, which strongly impact the environment of the entire Galaxy. Therefore, understanding the formation of massive stars is of great importance.

- At a distance of about 26,000 light-years away from us, the Galactic Center is a unique and important star-forming environment. The most well-known object here would undoubtedly be the supermassive black hole Sgr A*. Besides that, there is a massive reservoir of dense molecular gas, mainly in the form of molecular hydrogen (H2), which is the raw material for star formation. The gas will start to form stars once gravitational collapse is initiated. However, direct observations of star-forming regions around the Galactic Center are challenging, given the considerable distance and the contamination from foreground gas between the Galactic Center and us. A very high resolution, combined with high sensitivity, is necessary to resolve details of star formation in this region.

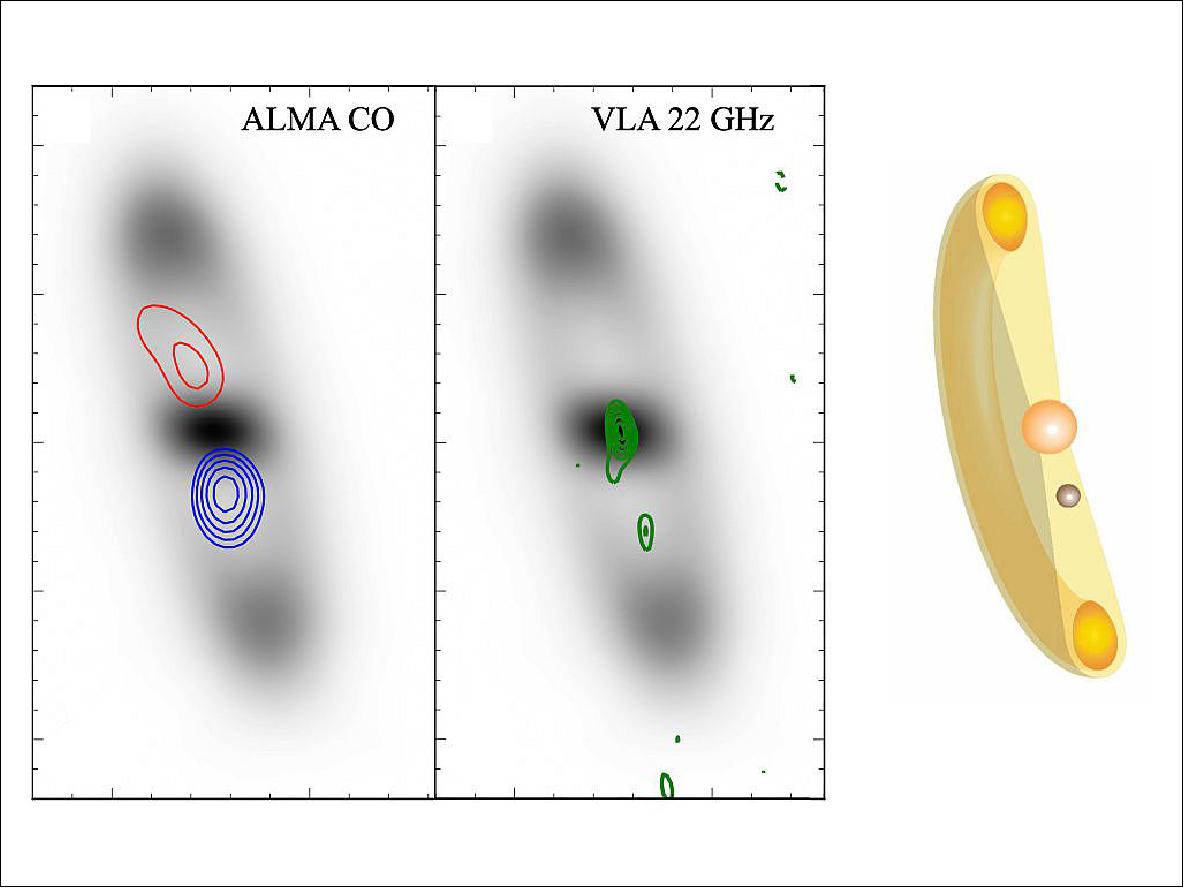

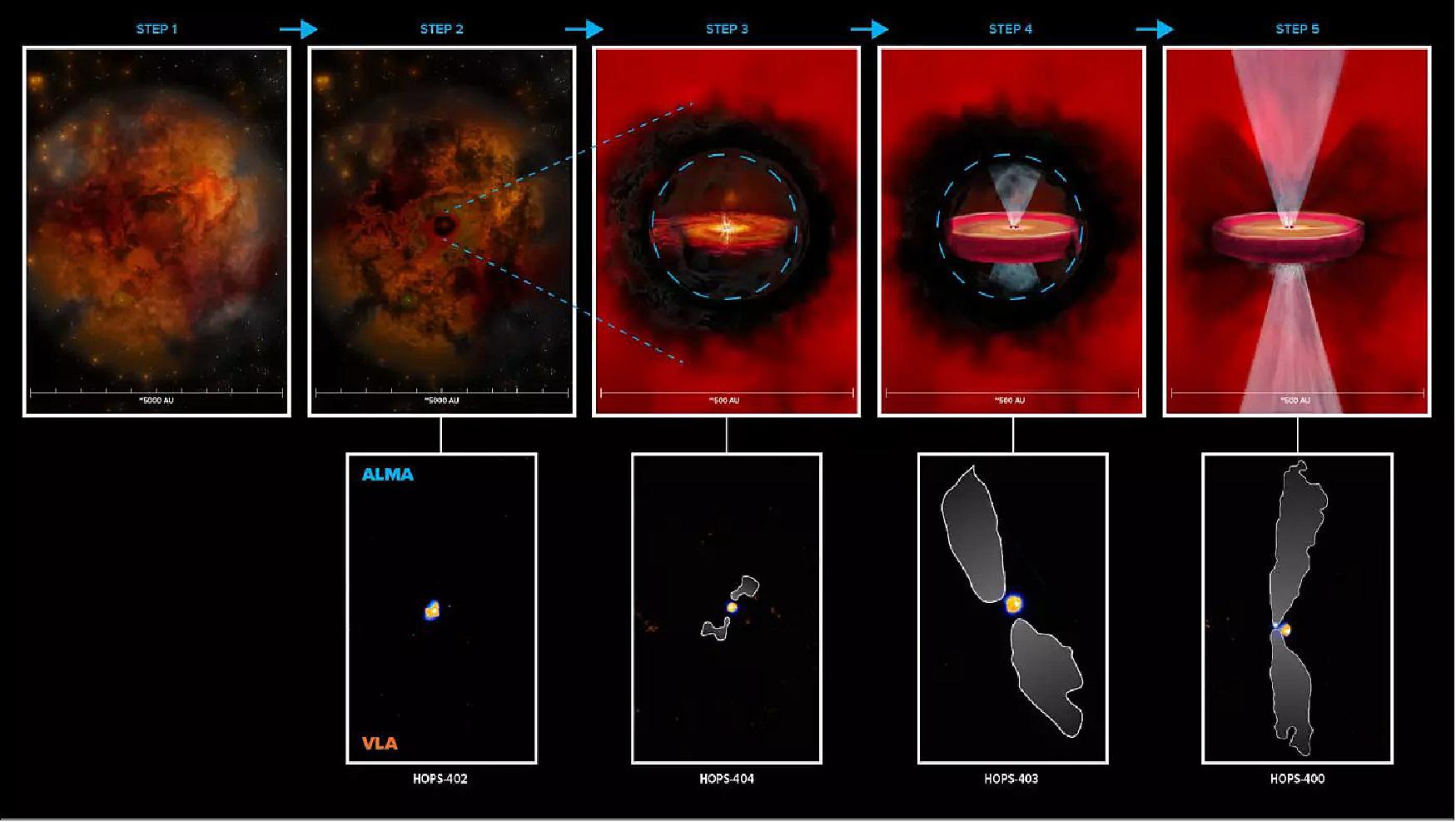

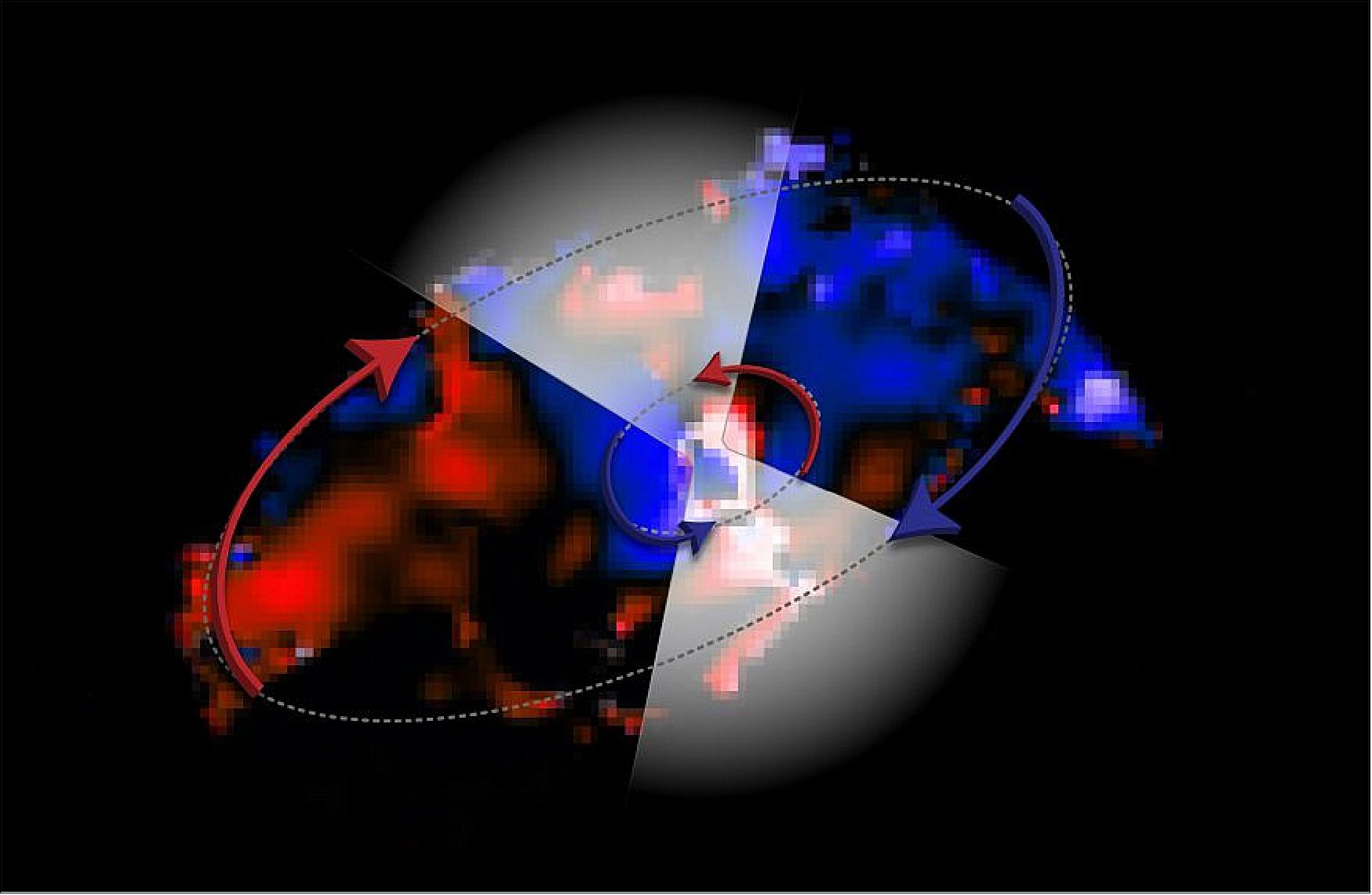

![Figure 17: A schematic view of the history of the accretion disk and the flyby object (a – c). The three plots starting from the bottom left are snapshots from the numerical simulation, capturing the system right at the flyby event, 4,000 years after, and 8,000 years after, respectively. The top right image is from the ALMA observations, showing the disk with spirals and the two objects around it, corresponding to the system at 12,000 years after the flyby event (d) [image credit: Lu et al.]](https://www.eoportal.org/ftp/satellite-missions/a/Alma_300622/Alma_Auto5C.jpeg)

- The research team has used the long-baseline observations of ALMA to achieve a resolution of 40 milliarcseconds. We can easily spot a baseball hidden in Osaka from Tokyo at such a resolution. With these high-resolution, high-sensitivityALMA observations, the team has discovered an accretion disk around the Galactic Center. The disk has a diameter of about 4,000 astronomical units and is surrounding a forming early O-type star of 32 solar mass. “This system is among the most massive protostars with accretion disks and represents the first direct imaging of a protostellar accretion disk in the Galactic Center,” said Qizhou Zhang, a co-author and an astrophysicist at the Center for Astrophysics. This discovery suggests that the formation of massive early O-type stars does go through a phase with accretion disks involved, and such a conclusion is valid for the Galactic Center.

- What is more interesting is that the disk clearly displays two spiral arms. Such spiral arms resemble those found in spiral galaxies but are rarely seen in protostellar disks. Spiral arms could emerge in accretion disks due to fragmentation induced by gravitational instabilities. However, the disk discovered in this study is hot and turbulent, thus able to balance its gravity. The team detected an object of about three solar masses at about 8,000 astronomical units away from the disk. Through a combined analysis of analytic solutions and numerical simulations, they reproduce a scenario where an object flew by the disk more than 10,000 years ago and perturbed the disk, leading to the formation of spiral arms. "The numerical simulation matches perfectly with the ALMA observations. We conclude that the spiral arms in the disk are relics of the flyby of the intruding object," said Xing Lu, the lead author and an associate researcher at the Shanghai Astronomical Observatory of the Chinese Academy of Sciences.

- This finding demonstrates that accretion disks at the early evolutionary stages of star formation are subject to frequent dynamic processes such as flybys, which would substantially influence the formation of stars and planets. It is interesting to note that flybys have also happened in our Solar System. A binary stellar system known as Scholz's Star flew by the solar system about 70,000 years ago, probably penetrating through the Oort cloud and sending comets to the inner solar system. This study suggests that for more massive stars, especially in the high stellar density environment around the Galactic Center, such flybys should also be frequent. "The formation of stars should be a dynamical process, with many mysteries still unresolved," said Xing Lu. "With more upcoming high-resolution ALMA observations, we expect to disentangle these mysteries in star formation."

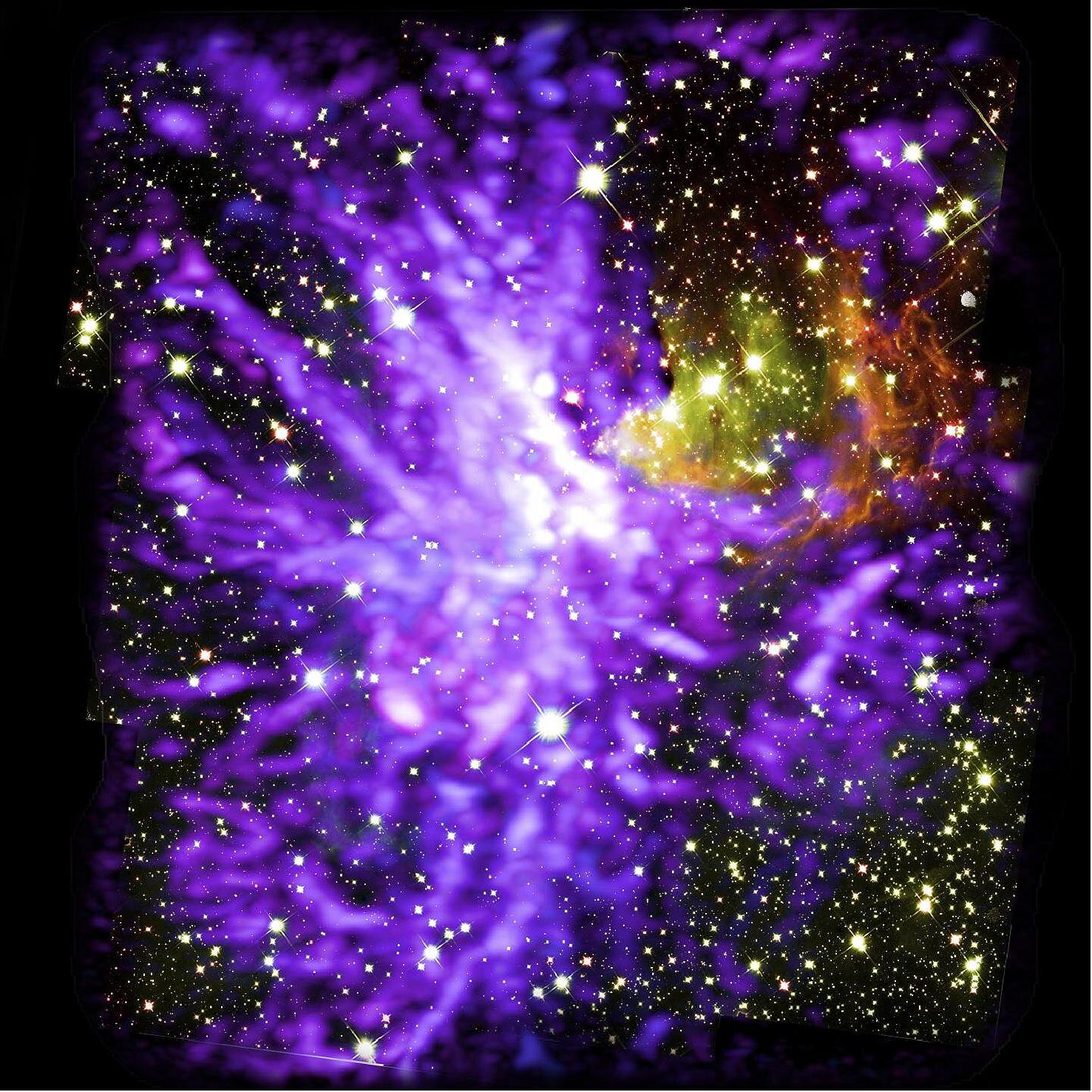

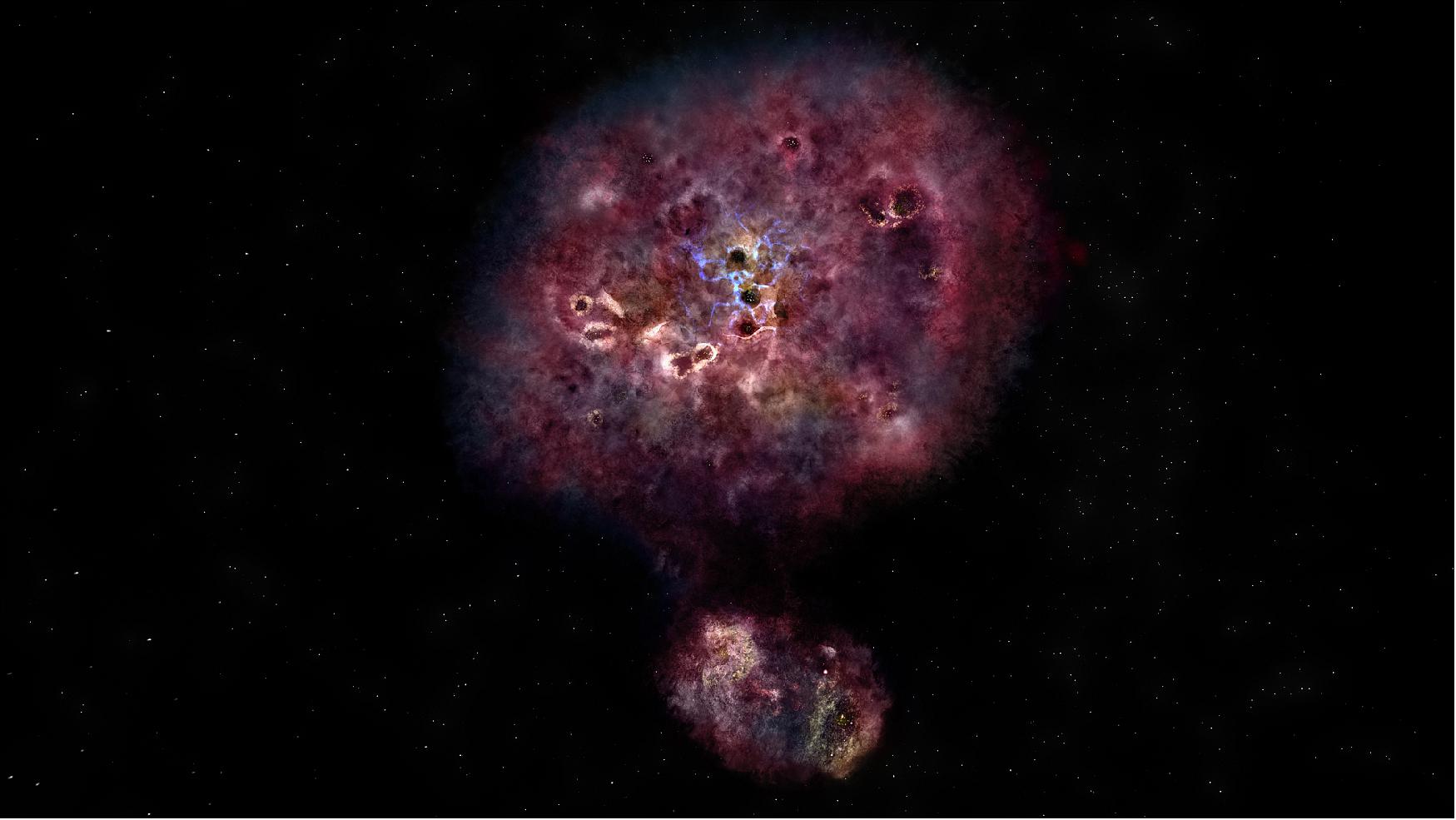

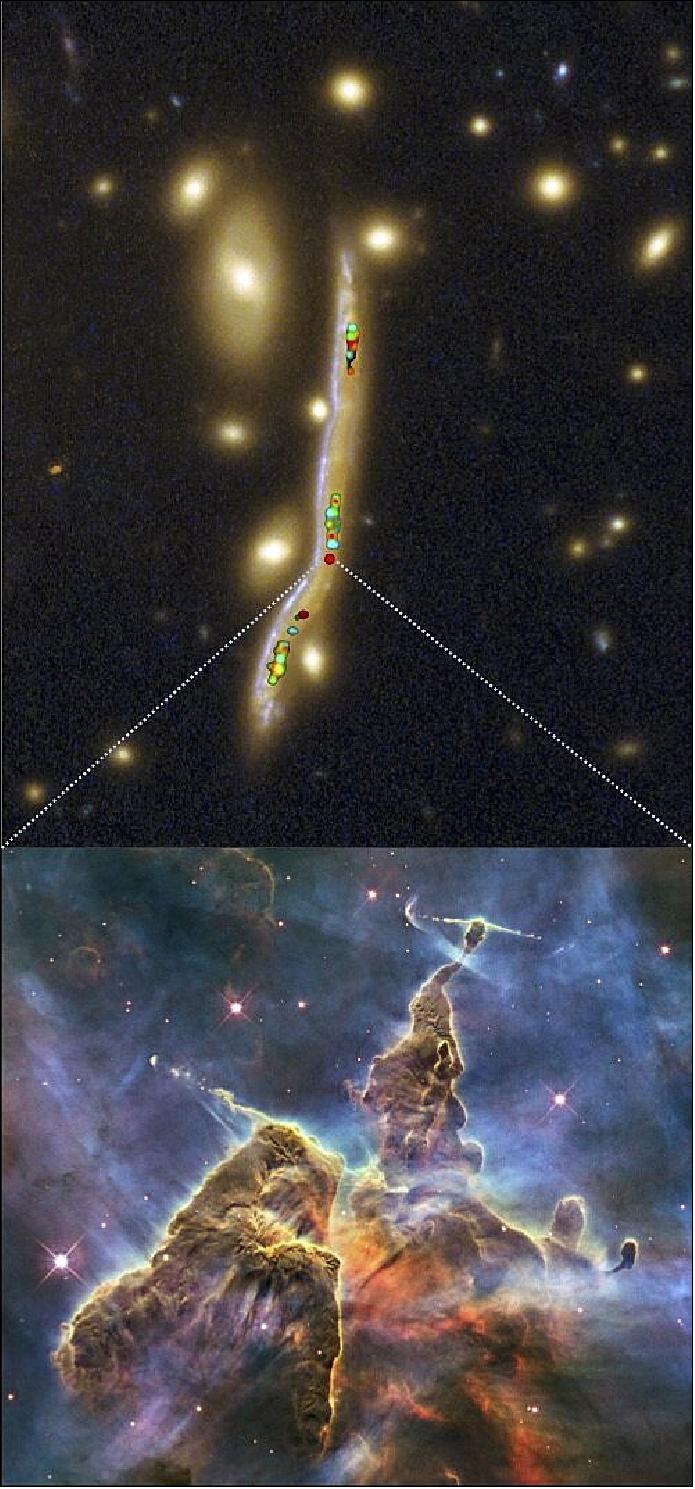

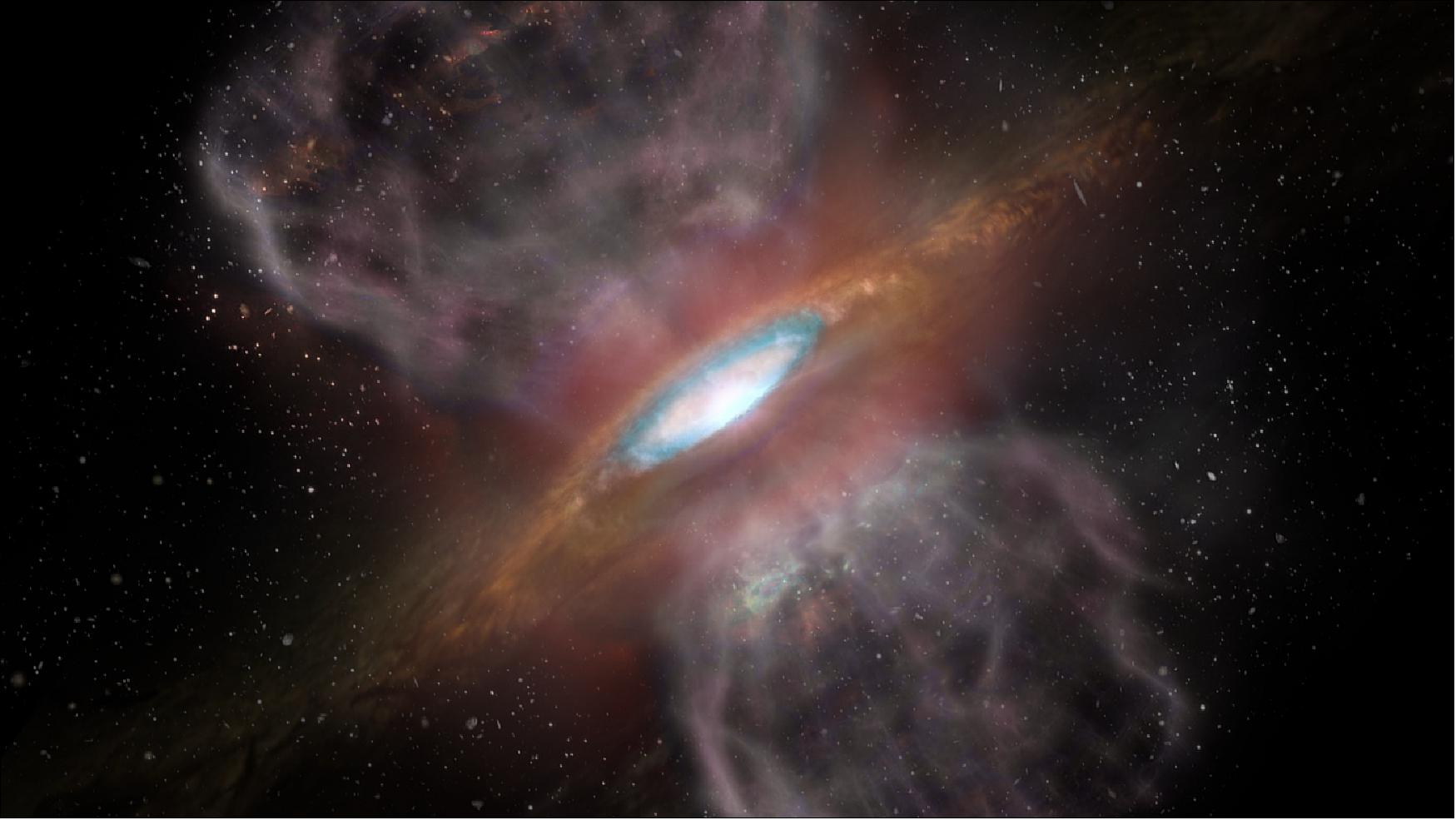

• June 15, 2022: Astronomers have unveiled intricate details of the star-forming region 30 Doradus, also known as the Tarantula Nebula, using new observations from the Atacama Large Millimeter/submillimeter Array (ALMA). In a high-resolution image released today by the European Southern Observatory (ESO) and including ALMA data, we see the nebula in a new light, with wispy gas clouds that provide insight into how massive stars shape this region. 31)

- “These fragments may be the remains of once-larger clouds that have been shredded by the enormous energy being released by young and massive stars, a process dubbed feedback,” says Tony Wong, who led the research on 30 Doradus presented today at the American Astronomical Society (AAS) meeting and published in The Astrophysical Journal. Astronomers originally thought the gas in these areas would be too sparse and too overwhelmed by this turbulent feedback for gravity to pull it together to form new stars. But the new data also reveal much denser filaments where gravity’s role is still significant. “Our results imply that even in the presence of very strong feedback, gravity can exert a strong influence and lead to a continuation of star formation,” adds Wong, who is a professor at the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, USA.

- Located in the Large Magellanic Cloud, a satellite galaxy of our own Milky Way, the Tarantula Nebula is one of the brightest and most active star-forming regions in our galactic neighbourhood, lying about 170,000 light-years away from Earth. At its heart are some of the most massive stars known, a few with more than 150 times the mass of our Sun, making the region perfect for studying how gas clouds collapse under gravity to form new stars.

- "What makes 30 Doradus unique is that it is close enough for us to study in detail how stars are forming, and yet its properties are similar to those found in very distant galaxies, when the Universe was young,” said Guido De Marchi, a scientist at the European Space Agency (ESA) and a co-author of the paper presenting the new research. “Thanks to 30 Doradus, we can study how stars used to form 10 billion years ago when most stars were born."

- While most of the previous studies of the Tarantula Nebula have focused on its centre, astronomers have long known that massive star formation is happening elsewhere too. To better understand this process, the team conducted high-resolution observations covering a large region of the nebula. Using ALMA, they measured the emission of light from carbon monoxide gas. This allowed them to map the large, cold gas clouds in the nebula that collapse to give birth to new stars — and how they change as huge amounts of energy are released by those young stars.

- “We were expecting to find that parts of the cloud closest to the young massive stars would show the clearest signs of gravity being overwhelmed by feedback,” says Wong. “We found instead that gravity is still important in these feedback-exposed regions — at least for parts of the cloud that are sufficiently dense.”

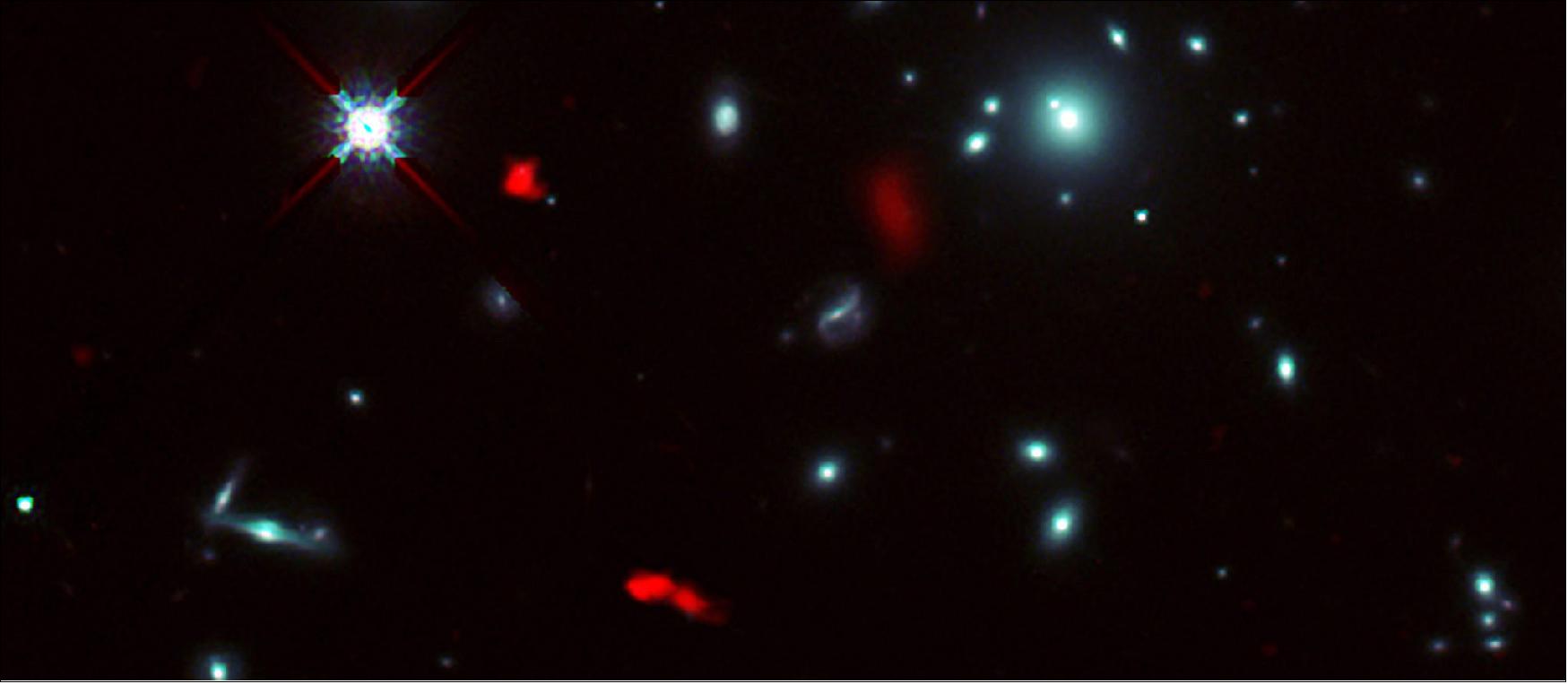

- In the image released today by ESO, we see the new ALMA data overlaid on a previous infrared image of the same region that shows bright stars and light pinkish clouds of hot gas, taken with ESO’s Very Large Telescope (VLT) and ESO’s Visible and Infrared Survey Telescope for Astronomy (VISTA). The composition shows the distinct, web-like shape of the Tarantula Nebula’s gas clouds that gave rise to its spidery name. The new ALMA data comprise the bright red-yellow streaks in the image: very cold and dense gas that could one day collapse and form stars.

- The new research contains detailed clues about how gravity behaves in the Tarantula Nebula’s star-forming regions, but the work is far from finished. “There is still much more to do with this fantastic data set, and we are releasing it publicly to encourage other researchers to conduct new investigations,” Wong concludes. 32)

• June 6, 2022: Resembling a curled sleeping snake, this picture shows NGC 1087. This spiral galaxy, located approximately 80 million light-years from Earth in the constellation of Cetus, is captured here by a combination of observations conducted at different wavelengths –– or colours –– of light. 33)

- But no need to worry, NGC 1087 will not poison you! The apparent menacing red glow actually corresponds to clouds of cold molecular gas, the raw material out of which stars form. Astronomers are able to image these clouds thanks to the Chile-based Atacama Large Millimeter/submillimeter Array (ALMA), in which ESO is a partner. The bluish regions in the background reveal the pattern of older, already formed stars, imaged by the Multi-Unit Spectroscopic Explorer (MUSE) on ESO’s Very Large Telescope (VLT) also in Chile.

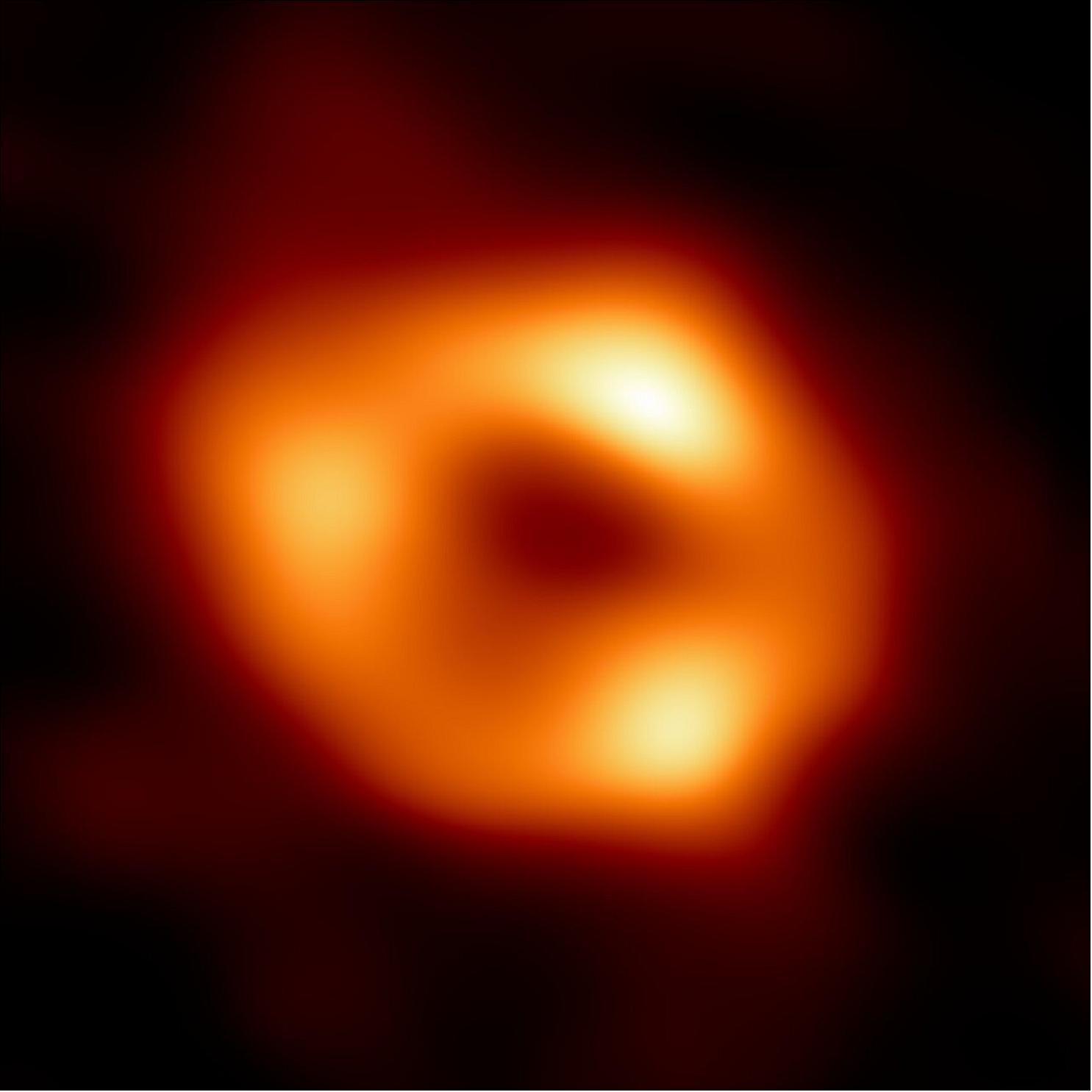

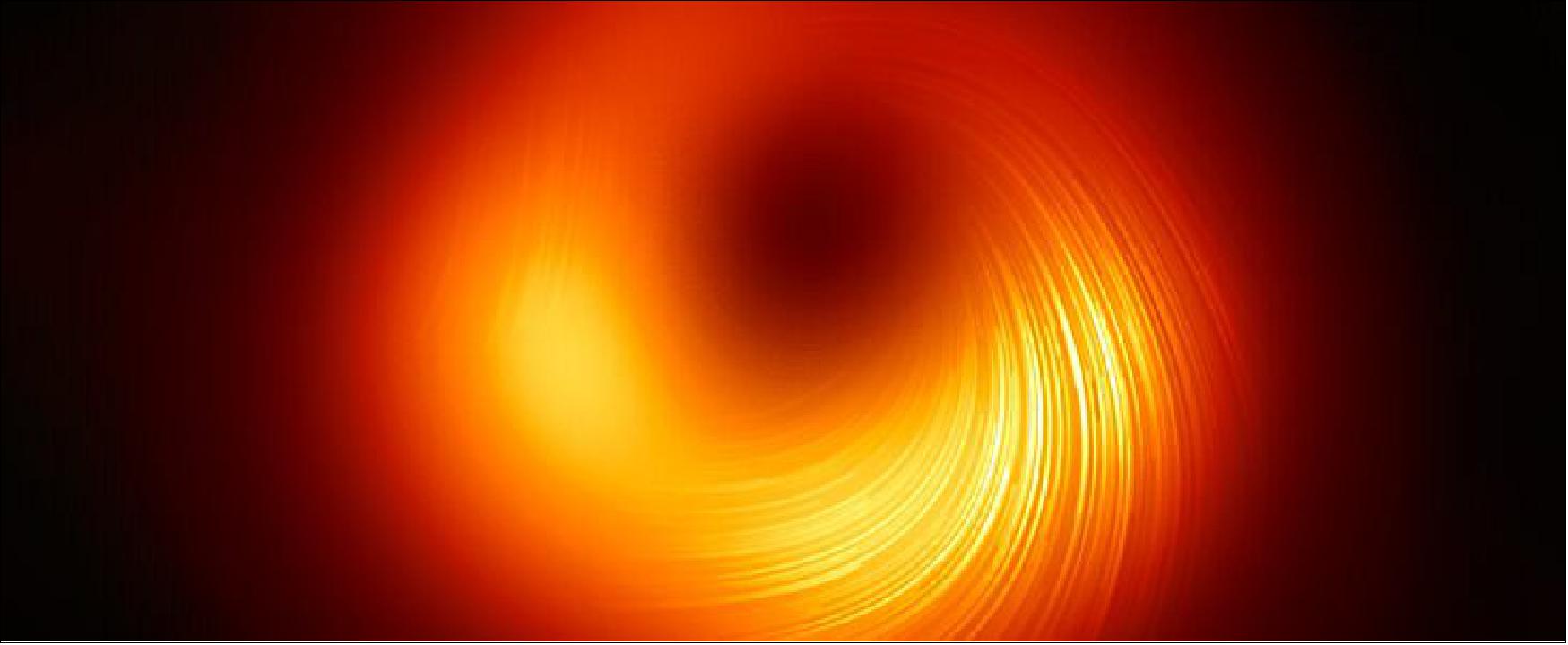

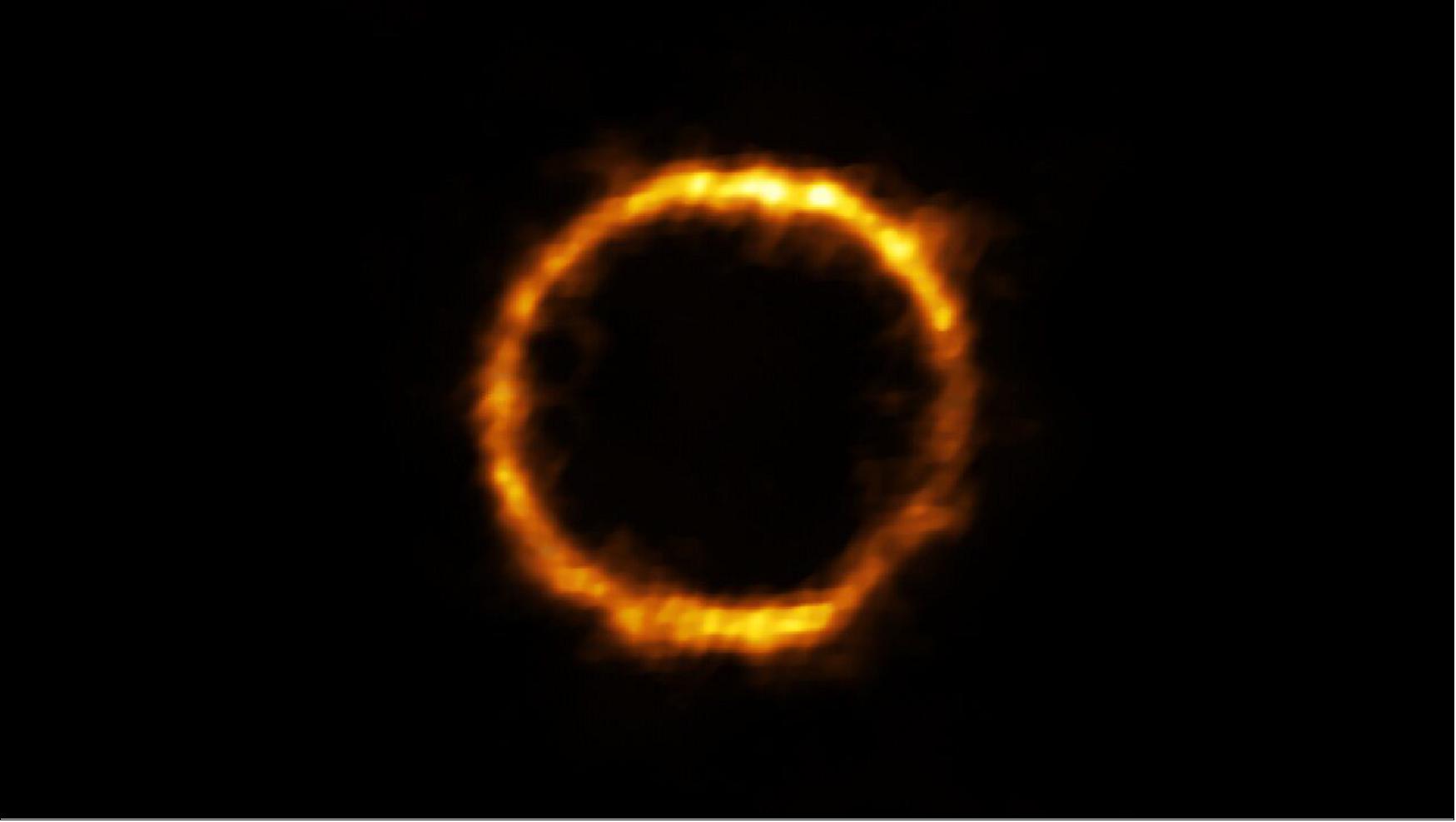

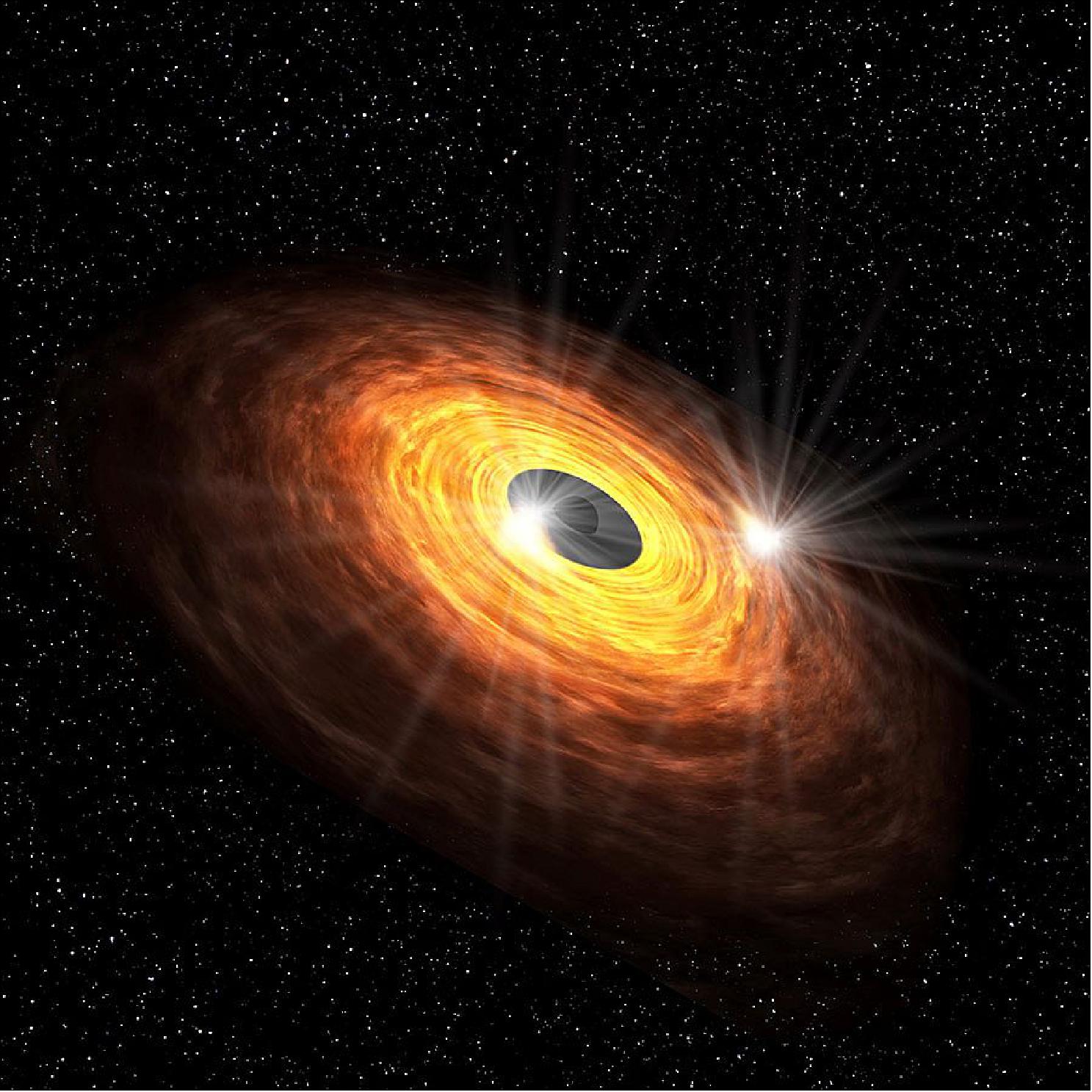

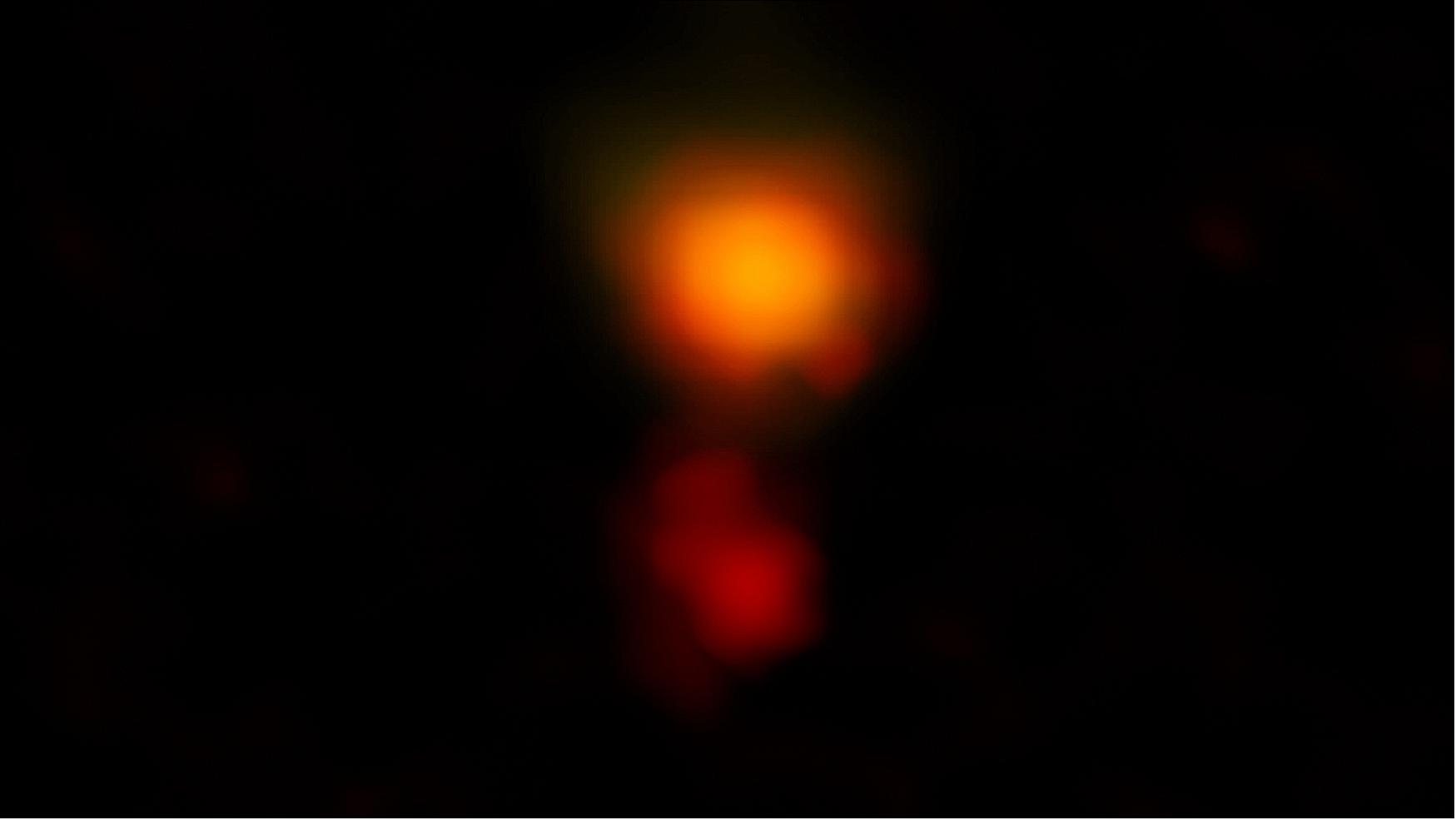

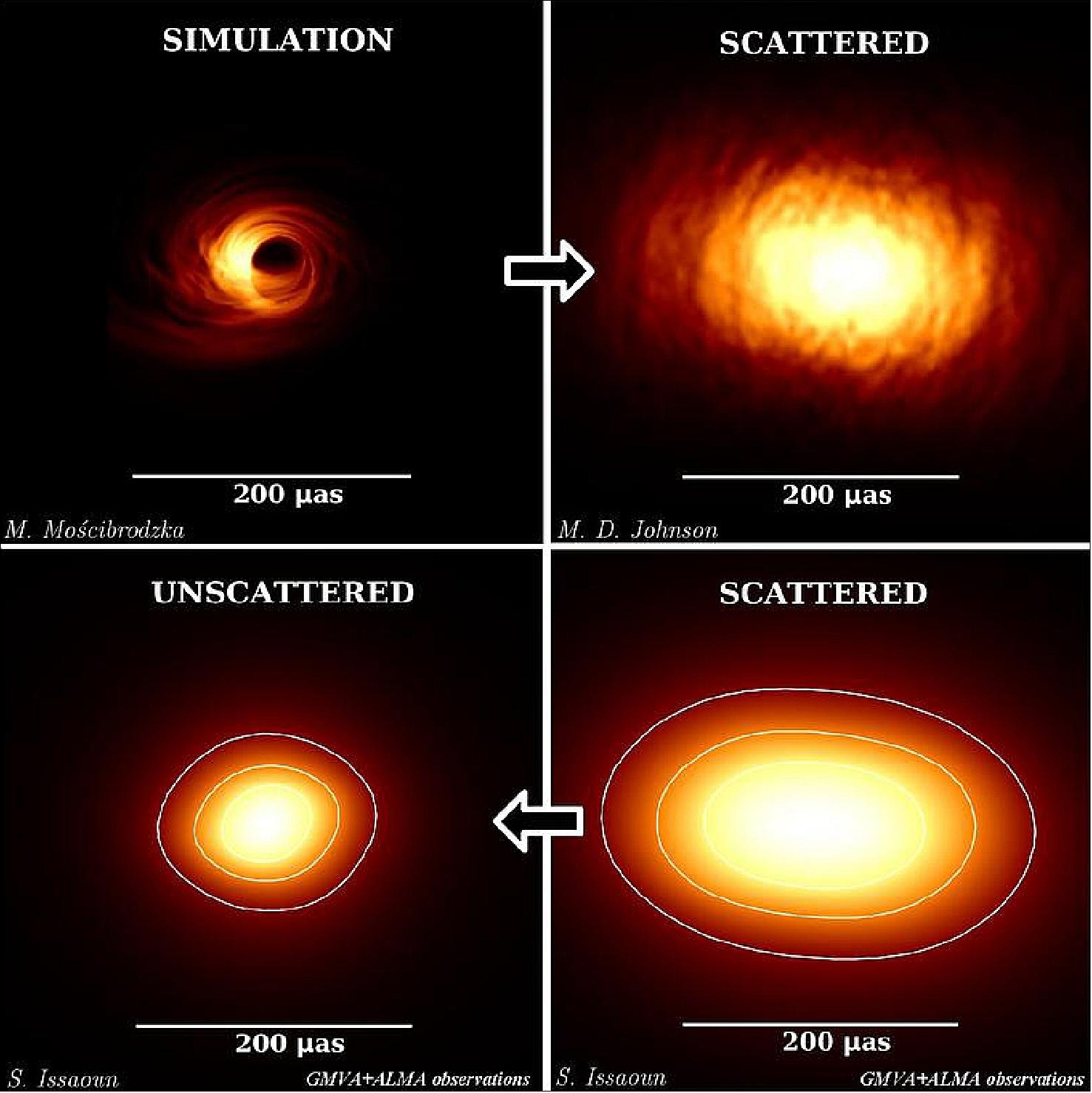

• May 12, 2022: Today, at simultaneous press conferences around the world, including at the European Southern Observatory (ESO) headquarters in Garching, Germany, astronomers have unveiled the first image of the supermassive black hole at the centre of our own Milky Way galaxy. This result provides overwhelming evidence that the object is indeed a black hole and yields valuable clues about the workings of such giants, which are thought to reside at the centre of most galaxies. The image was produced by a global research team called the Event Horizon Telescope (EHT) Collaboration, using observations from a worldwide network of radio telescopes. 34)

- The image is a long-anticipated look at the massive object that sits at the very centre of our galaxy. Scientists had previously seen stars orbiting around something invisible, compact, and very massive at the centre of the Milky Way. This strongly suggested that this object — known as Sagittarius A* (Sgr A*, pronounced "sadge-ay-star") — is a black hole, and today’s image provides the first direct visual evidence of it.

- Although we cannot see the black hole itself, because it is completely dark, glowing gas around it reveals a telltale signature: a dark central region (called a shadow) surrounded by a bright ring-like structure. The new view captures light bent by the powerful gravity of the black hole, which is four million times more massive than our Sun.

- “We were stunned by how well the size of the ring agreed with predictions from Einstein’s Theory of General Relativity," said EHT Project Scientist Geoffrey Bower from the Institute of Astronomy and Astrophysics, Academia Sinica, Taipei. "These unprecedented observations have greatly improved our understanding of what happens at the very centre of our galaxy, and offer new insights on how these giant black holes interact with their surroundings." The EHT team's results are being published today in a special issue of The Astrophysical Journal Letters. 35)

- Because the black hole is about 27,000 light-years away from Earth, it appears to us to have about the same size in the sky as a doughnut on the Moon. To image it, the team created the powerful EHT, which linked together eight existing radio observatories across the planet to form a single “Earth-sized” virtual telescope [1]. The EHT observed Sgr A* on multiple nights in 2017, collecting data for many hours in a row, similar to using a long exposure time on a camera.

- In addition to other facilities, the EHT network of radio observatories includes the Atacama Large Millimeter/submillimeter Array (ALMA) and the Atacama Pathfinder EXperiment (APEX) in the Atacama Desert in Chile, co-owned and co-operated by ESO on behalf of its member states in Europe. Europe also contributes to the EHT observations with other radio observatories — the IRAM 30-meter telescope in Spain and, since 2018, the NOrthern Extended Millimeter Array (NOEMA) in France — as well as a supercomputer to combine EHT data hosted by the Max Planck Institute for Radio Astronomy in Germany. Moreover, Europe contributed with funding to the EHT consortium project through grants by the European Research Council and by the Max Planck Society in Germany.

- “It is very exciting for ESO to have been playing such an important role in unravelling the mysteries of black holes, and of Sgr A* in particular, over so many years,” commented ESO Director General Xavier Barcons. “ESO not only contributed to the EHT observations through the ALMA and APEX facilities but also enabled, with its other observatories in Chile, some of the previous breakthrough observations of the Galactic centre.” [2]

- The EHT achievement follows the collaboration’s 2019 release of the first image of a black hole, called M87*, at the centre of the more distant Messier 87 galaxy.

- The two black holes look remarkably similar, even though our galaxy’s black hole is more than a thousand times smaller and less massive than M87* [3]. "We have two completely different types of galaxies and two very different black hole masses, but close to the edge of these black holes they look amazingly similar,” says Sera Markoff, Co-Chair of the EHT Science Council and a professor of theoretical astrophysics at the University of Amsterdam, the Netherlands. "This tells us that General Relativity governs these objects up close, and any differences we see further away must be due to differences in the material that surrounds the black holes.”

- This achievement was considerably more difficult than for M87*, even though Sgr A* is much closer to us. EHT scientist Chi-kwan (‘CK’) Chan, from Steward Observatory and Department of Astronomy and the Data Science Institute of the University of Arizona, USA, explains: “The gas in the vicinity of the black holes moves at the same speed — nearly as fast as light — around both Sgr A* and M87*. But where gas takes days to weeks to orbit the larger M87*, in the much smaller Sgr A* it completes an orbit in mere minutes. This means the brightness and pattern of the gas around Sgr A* were changing rapidly as the EHT Collaboration was observing it — a bit like trying to take a clear picture of a puppy quickly chasing its tail.”

- The researchers had to develop sophisticated new tools that accounted for the gas movement around Sgr A*. While M87* was an easier, steadier target, with nearly all images looking the same, that was not the case for Sgr A*. The image of the Sgr A* black hole is an average of the different images the team extracted, finally revealing the giant lurking at the centre of our galaxy for the first time.

- The effort was made possible through the ingenuity of more than 300 researchers from 80 institutes around the world that together make up the EHT Collaboration. In addition to developing complex tools to overcome the challenges of imaging Sgr A*, the team worked rigorously for five years, using supercomputers to combine and analyse their data, all while compiling an unprecedented library of simulated black holes to compare with the observations.

- Scientists are particularly excited to finally have images of two black holes of very different sizes, which offers the opportunity to understand how they compare and contrast. They have also begun to use the new data to test theories and models of how gas behaves around supermassive black holes. This process is not yet fully understood but is thought to play a key role in shaping the formation and evolution of galaxies.

- “Now we can study the differences between these two supermassive black holes to gain valuable new clues about how this important process works,” said EHT scientist Keiichi Asada from the Institute of Astronomy and Astrophysics, Academia Sinica, Taipei. “We have images for two black holes — one at the large end and one at the small end of supermassive black holes in the Universe — so we can go a lot further in testing how gravity behaves in these extreme environments than ever before.”

- Progress on the EHT continues: a major observation campaign in March 2022 included more telescopes than ever before. The ongoing expansion of the EHT network and significant technological upgrades will allow scientists to share even more impressive images as well as movies of black holes in the near future.

![Figure 23: Size comparison of the two black holes imaged by the Event Horizon Telescope (EHT) Collaboration: M87*, at the heart of the galaxy Messier 87, and Sagittarius A* (Sgr A*), at the centre of the Milky Way. The image shows the scale of Sgr A* in comparison with both M87* and other elements of the Solar System such as the orbits of Pluto and Mercury. Also displayed is the Sun’s diameter and the current location of the Voyager 1 space probe, the furthest spacecraft from Earth. M87*, which lies 55 million light-years away, is one of the largest black holes known. While Sgr A*, 27 000 light-years away, has a mass roughly four million times the Sun’s mass, M87* is more than 1000 times more massive. Because of their relative distances from Earth, both black holes appear the same size in the sky. [image credit: EHT collaboration (acknowledgment: Lia Medeiros, xkcd)] 36)](https://www.eoportal.org/ftp/satellite-missions/a/Alma_300622/Alma_Auto56.jpeg)

• May 12, 2022: The black hole at the center of our galaxy is the subject of a groundbreaking new image from the Event Horizon Telescope (EHT) collaboration. — As the Event Horizon Telescope collected data for its remarkable new image of the Milky Way’s supermassive black hole, a legion of other telescopes including three NASA X-ray observatories in space was also watching. 37)

- Astronomers are using these observations to learn more about how the black hole in the center of the Milky Way galaxy – known as Sagittarius A * (Sgr A* for short) – interacts with, and feeds off, its environment some 27,000 light years from Earth.

![Figure 24: This composite image of the supermassive black hole at the center of the Milky Way galaxy includes data from multiple NASA telescopes. The inset image from the Event Horizon Telescope shows the region around the black hole’s event horizon, the boundary beyond which not even light can escape [image credit: X-ray: NASA/CXC/SAO; IR: NASA/HST/STScI. Inset: Radio (EHT Collaboration)]](https://www.eoportal.org/ftp/satellite-missions/a/Alma_300622/Alma_Auto55.jpeg)

- When the Event Horizon Telescope (EHT) observed Sgr A* in April 2017 to make the new image, scientists in the collaboration also peered at the same black hole with facilities that detect different wavelengths of light. In this multiwavelength observing campaign, they assembled X-ray data from NASA’s Chandra X-ray Observatory, Nuclear Spectroscopic Telescope Array (NuSTAR), and the Neil Gehrels Swift Observatory; radio data from the East Asian Very Long-Baseline Interferometer (VLBI) network and the Global 3-millimeter VLBI array; and infrared data from the European Southern Observatory’s Very Large Telescope in Chile.

- “The Event Horizon Telescope has captured yet another remarkable image, this time of the giant black hole at the center of our own home galaxy,” said NASA Administrator Bill Nelson. “Looking more comprehensively at this black hole will help us learn more about its cosmic effects on its environment, and exemplifies the international collaboration that will carry us into the future and reveal discoveries we could never have imagined.”

- One important goal was to catch X-ray flares, which are thought to be driven by magnetic processes similar to those seen on the Sun, but can be tens of millions of times more powerful. These flares occur approximately daily within the area of sky observed by the EHT, a region slightly larger than the event horizon of Sgr A*, the point of no return for matter falling inward. Another goal was to gain a critical glimpse of what is happening on larger scales. While the EHT result shows striking similarities between Sgr A* and the previous black hole it imaged, M87*, the wider picture is much more complex.

- “If the new EHT image shows us the eye of a black hole hurricane, then these multiwavelength observations reveal winds and rain the equivalent of hundreds or even thousands of miles beyond,” said Daryl Haggard of McGill University in Montreal, Canada, who is one of the lead scientists of the multiwavelength campaign. “How does this cosmic storm interact with and even disrupt its galactic environment?”

- One of the biggest ongoing questions surrounding black holes is exactly how they collect, ingest, or even expel material orbiting them at near light speed, in a process known as “accretion.” This process is fundamental to the formation and growth of planets, stars, and black holes of all sizes, throughout the universe.

- Chandra images of hot gas around Sgr A* are crucial for accretion studies because they tell us how much material is captured from nearby stars by the black hole’s gravity, as well as how much manages to make its way close to the event horizon. This critical information is not available with current telescopes for any other black hole in the universe, including M87*.

- “Astronomers can largely agree on the basics – that black holes have material swirling around them and some of it falls across the event horizon forever,” said Sera Markoff of the University of Amsterdam in the Netherlands, another coordinator of the multiwavelength observations. “With all of the data that we’ve gathered for Sgr A* we can go a lot further than this basic picture.”

- Scientists in the large international collaboration compared the data from NASA’s high-energy missions and the other telescopes to state-of-the-art computational models that take into account factors such as Einstein’s general theory of relativity, effects of magnetic fields, and predictions of how much radiation the material around the black hole should generate at different wavelengths.

- The comparison of the models with the measurements gives hints that the magnetic field around the black hole is strong and that the angle between the line of sight to the black hole and its spin-axis is low – less than about 30 degrees. If confirmed this means that from our vantage point we are looking down on Sgr A* and its ring more than we are from side-on, surprisingly similar to EHT’s first target, M87*.

- “None of our models matches the data perfectly, but now we have more specific information to work from,” said Kazuhiro Hada from the National Astronomical Observatory of Japan. “The more data we have the more accurate our models, and ultimately our understanding of black hole accretion, will become.”

- The researchers also managed to catch X-ray flares – or outbursts – from Sgr A* during the EHT observations: a faint one seen with Chandra and Swift, and a moderately bright one seen with Chandra and NuSTAR. X-ray flares with a similar brightness to the latter are regularly observed with Chandra, but this is the first time that the EHT simultaneously observed Sgr A*, offering an extraordinary opportunity to identify the responsible mechanism using actual images.

- The millimeter-wave intensity and variability observed with EHT increases in the few hours immediately after the brighter X-ray flare, a phenomenon not seen in millimeter observations a few days earlier. Analysis and interpretation of the EHT data immediately following the flare will be reported in future publications.

- The EHT team’s results are being published on May 12 in a special issue of The Astrophysical Journal Letters. The multiwavelength results are mainly described in papers II and V.

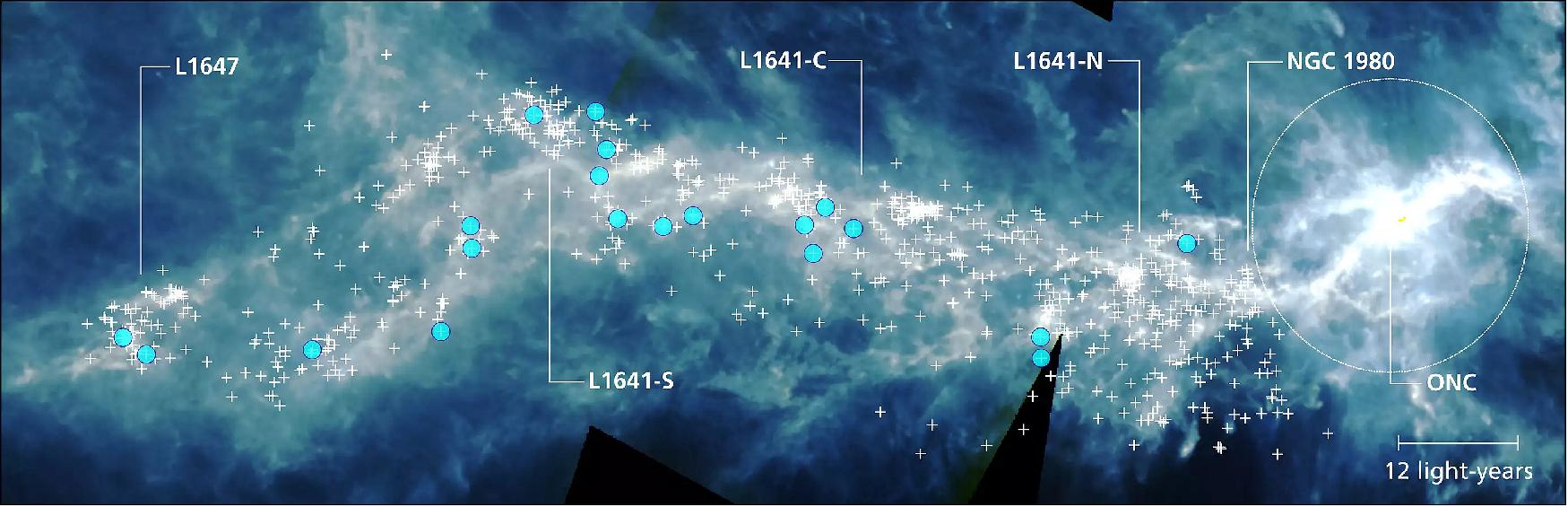

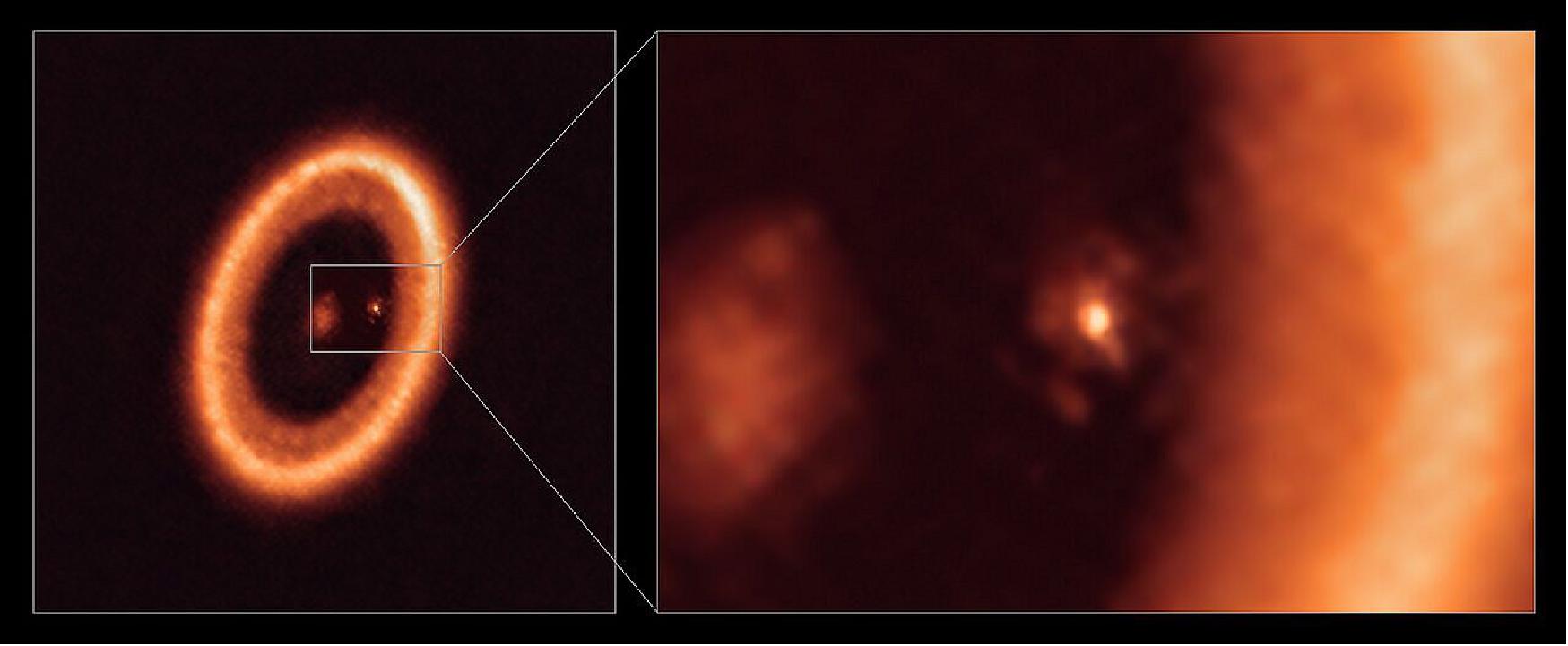

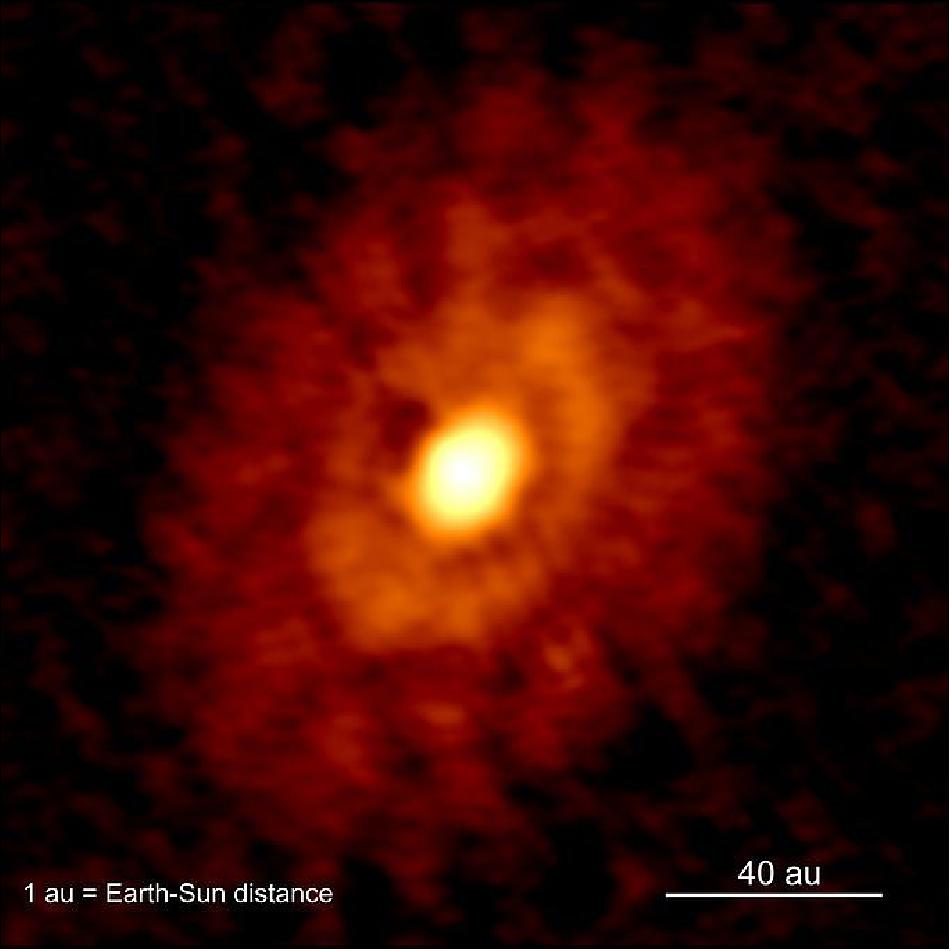

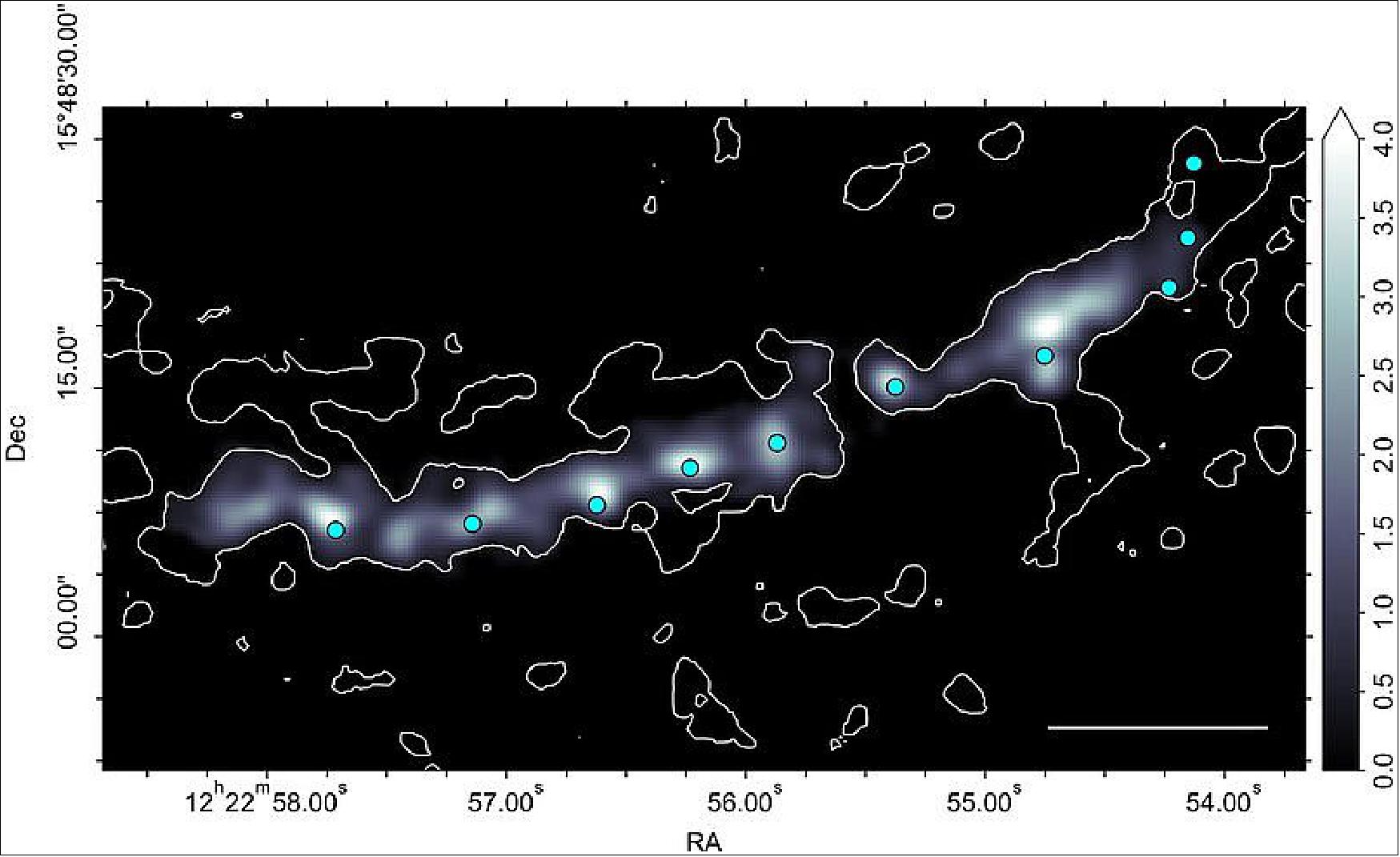

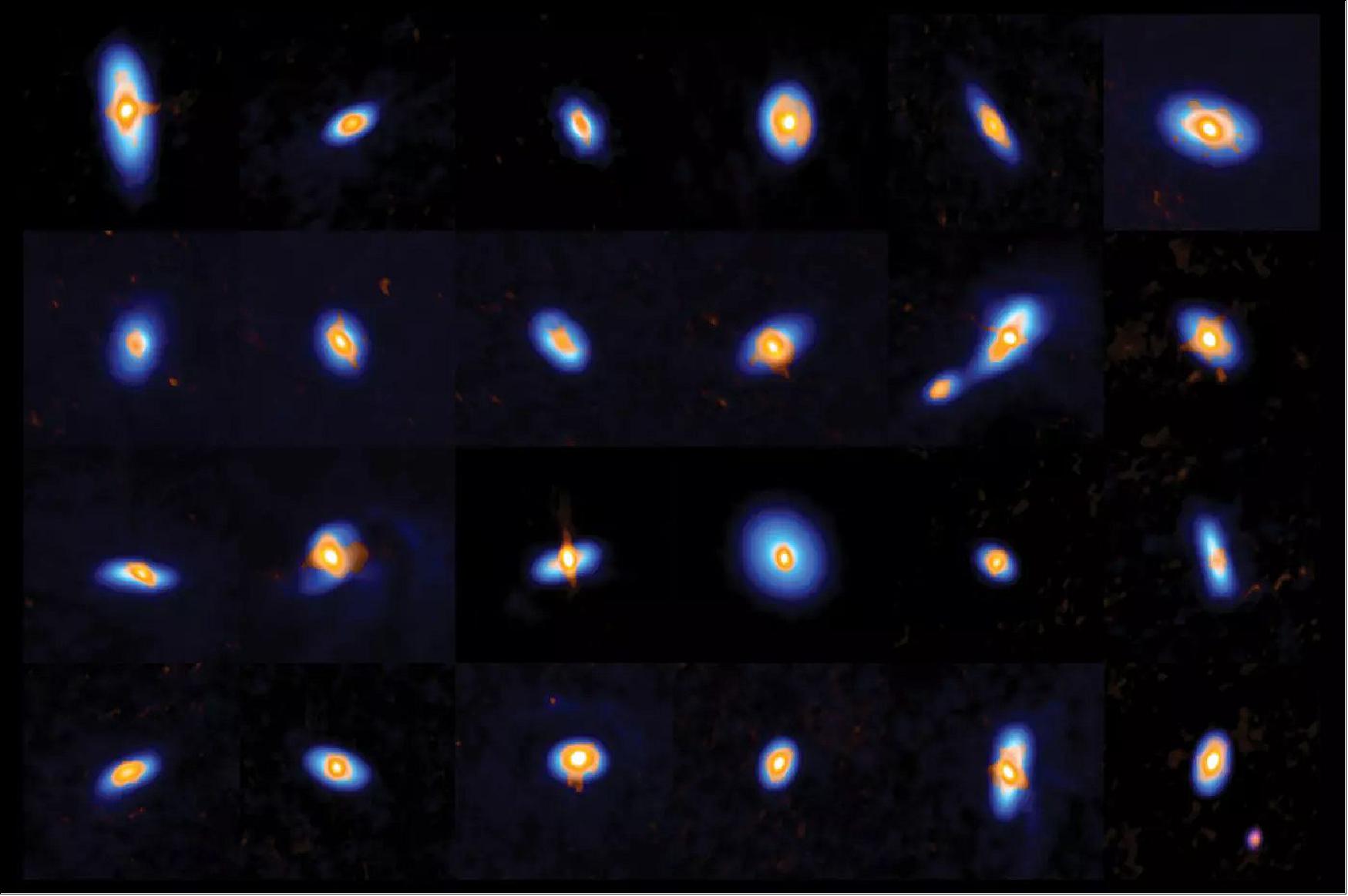

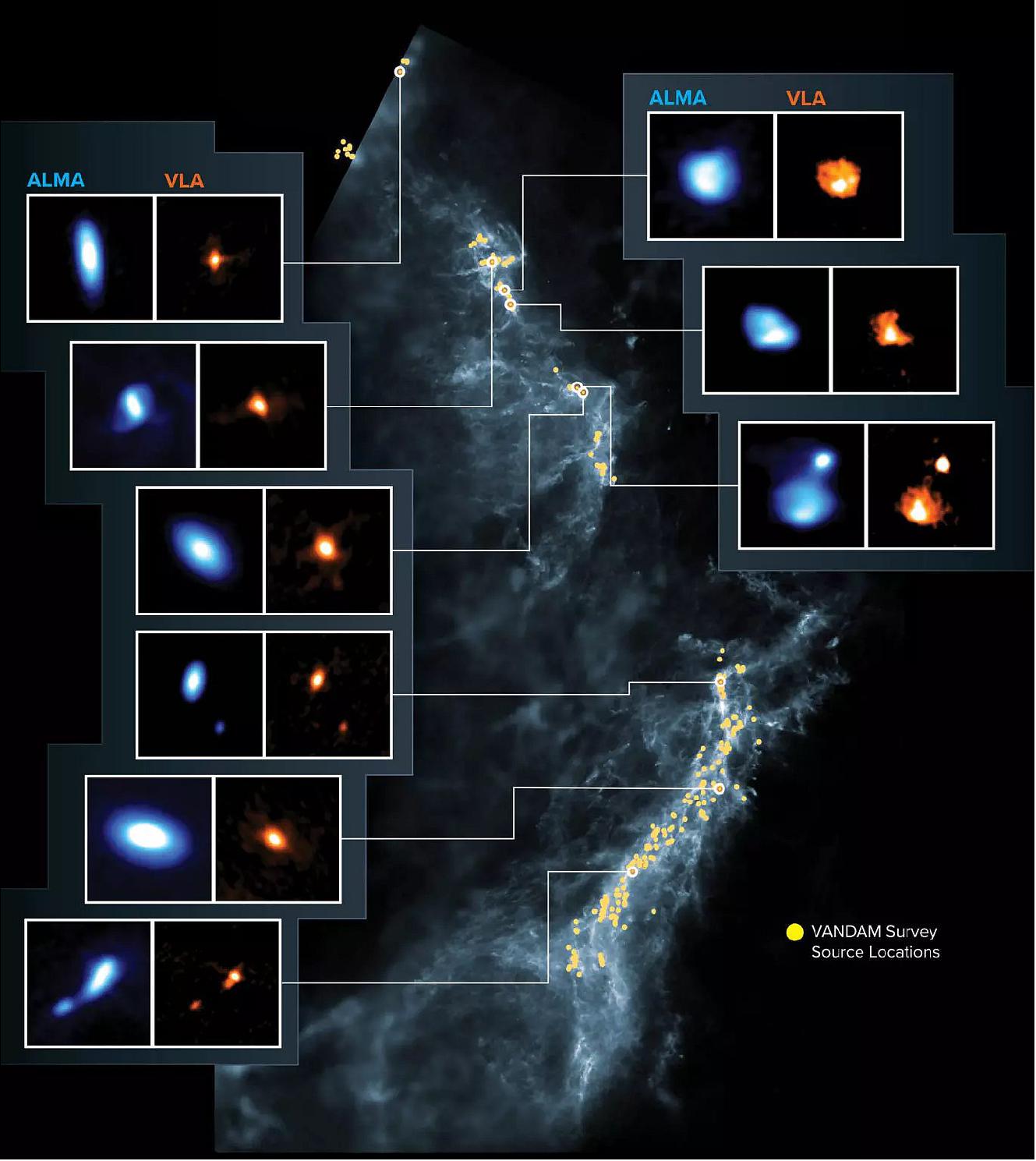

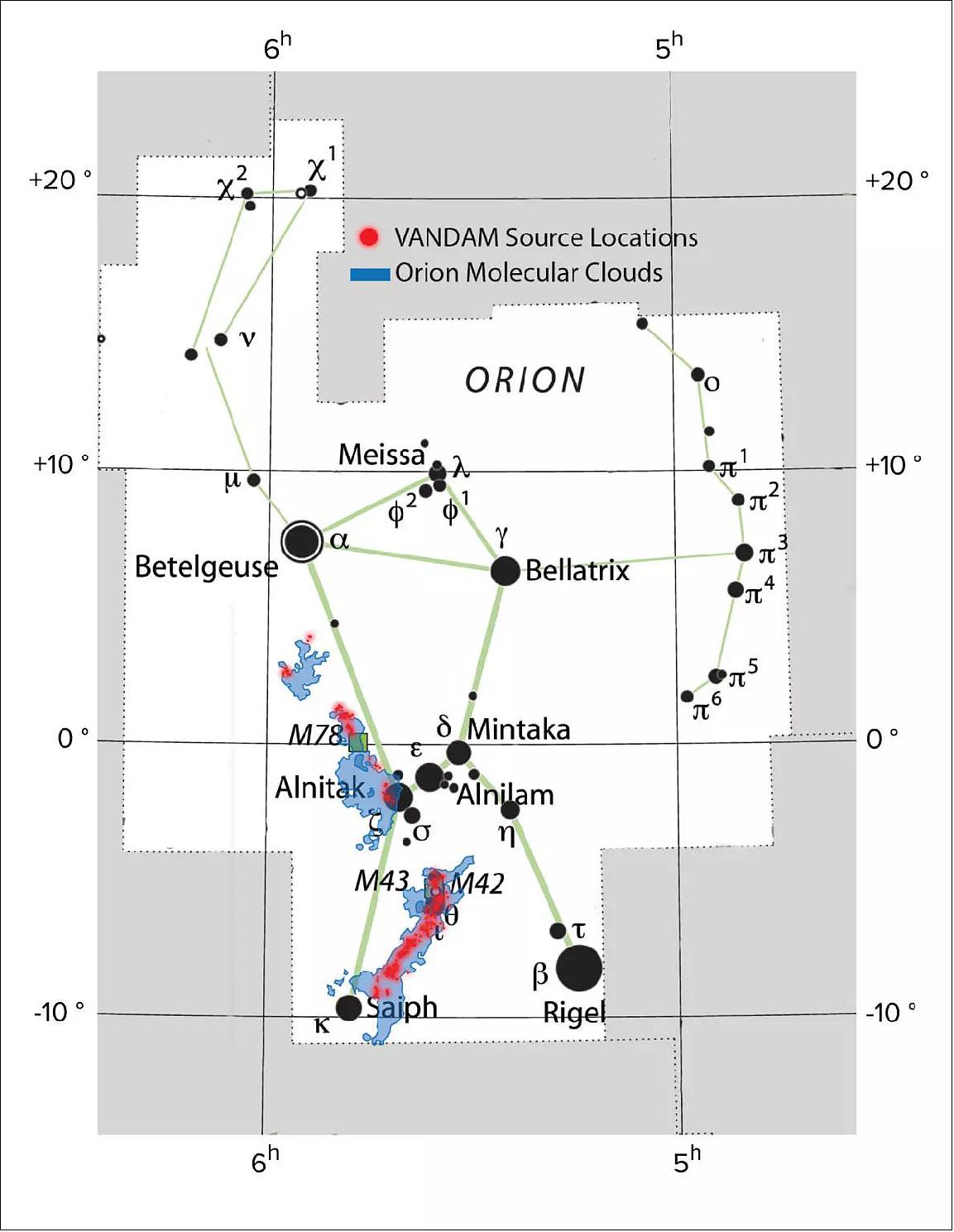

• May 6, 2022: A group of astronomers, led by Sierk van Terwisga from the Max Planck Institute for Astronomy (MPIA), have analysed the mass distribution of over 870 planet-forming disks in the Orion A cloud. By exploiting the statistical properties of this unprecedented large sample of disks and developing an innovative data processing scheme, they found that far away from harsh environments like hot stars, the decline in disk mass only depends on their age. The results indicate that, at least within 1000 light-years of the Earth, planet-forming disks and planetary systems evolve in similar ways. 38) 39)

Some of the most exciting questions in present-day astronomical research are: What do other planetary systems look like? How comparable is the Solar System to other planetary systems? A team of astronomers have now contributed crucial clues to solving this puzzle. “Up to now, we didn’t know for sure which properties dominate the evolution of planet-forming disks around young stars”, says Sierk van Terwisga, who is a scientist at the Max Planck Institute for Astronomy in Heidelberg, Germany. He is the lead author of the underlying research article published in Astronomy & Astrophysics today. “Our new results now indicate that in environments without any relevant external influence, the observed disk mass available for forming new planets only depends on the age of the star-disk system”, van Terwisga adds.

- The disk mass is the key property when studying the evolution of planet-forming disks. This quantity determines how much material is available to be transformed into planets. Depending on the disk age, it may also provide clues about the planets already present there. External effects like irradiation and winds from nearby massive stars obviously impact the disk survival. However, such environments are rare, and those processes do not reveal much about the disks themselves. Instead, astronomers are more interested in internal disk properties such as age, chemical composition, or the parental cloud dynamics from which the young stars with their disks emerged.

- To disentangle the various contributions, the team of astronomers selected a large and well-known region of young stars with disks, the Orion A cloud. It is approximately 1350 light-years away from Earth. “Orion A provided us with an unprecedented large sample size of more than 870 disks around young stars. It was crucial to be able to look for small variations in the disk mass depending on age and even on the local environments inside the cloud,” Álvaro Hacar, a co-author and scientist at the University of Vienna, Austria, explains. The sample stems from earlier observations with the Herschel Space Telescope, which permitted identifying the disks. Combining several wavelengths provided a criterion to estimate their ages. Since they all belong to the same cloud, the astronomers expected little influence from chemistry and cloud history variations. They also avoided any impact from massive stars in the nearby Orion Nebula Cluster (ONC) by rejecting disks closer than 13 light-years.

- To measure the disk mass, the team employed the Atacama Large Millimeter/Submillimeter Array (ALMA) located on the Chajnantor Plateau in the Chilean Atacama Desert. ALMA consists of 66 parabolic antennas, functioning as a single telescope with a tunable angular resolution. The scientists applied an observing mode that allowed them to target each disk efficiently at a wavelength of about 1.2 mm. The cold disks are bright in this spectral range. On the other hand, the central stars’ contribution is negligible. With this approach, the astronomers determined the disks’ dust masses. However, the observations are insensitive to objects much larger than a few millimetres, e.g. rocks and planets. Therefore, the team effectively measured the mass of the disk material capable of forming planets.

- Before calculating the disk masses, the astronomers combined and calibrated the data from several dozens of ALMA telescopes. This task becomes quite a challenge when dealing with large data sets. Using standard methods, it would have taken months to process the collected data. Instead, the team developed a new method using parallel computers. “Our new approach improved the processing speed by a factor of 900,” co-author Raymond Oonk from the collaborating IT service provider SURF points out. The 3000 CPU hours required to finish the task and prepare the data for subsequent analysis elapsed in less than a day.

- Altogether, Orion A contains planet-forming disks, each with dust amounting to up to a few hundred Earth-masses. However, from the 870 disks, only 20 hold dust equivalent to 100 earths or more. In general, the number of disks declines rapidly with mass, with a majority containing less than 2.2 Earth-masses of dust. “In order to look for variations, we have dissected the Orion A cloud and analysed these regions separately. Thanks to the hundreds of disks, the sub-samples were still sufficiently large to yield statistically meaningful results”, van Terwisga explains.

- Indeed, the scientists found minor variations in the disk mass distributions on scales of tens of light-years within Orion A. However, all of them can be explained as an age effect, meaning within a few million years, disk masses tend to decline towards older populations. Within the error margins, clusters of planet-forming disks of the same age exhibit the same mass distribution. It is not at all surprising to find the dust mass in planet-forming disks to decrease in time. After all, dust is one of the raw materials for planets. Hence, planet formation certainly reduces the amount of free dust. Other well-known processes are dust migration towards the disk centre and dust evaporation by irradiation from the host star. Still, it is surprising to see such a strong correlation between disk mass and age.

- All those disks emerged from the same environment that now constitutes the Orion A cloud. How does this compare to other young star-disk populations? The astronomers addressed this question by comparing their results to several nearby star-forming regions with planet-forming disks. Except for two, all of them nicely fit the mass-age relation found in Orion A. “Altogether, we think our study proves that at least within the next 1000 light-years or so, all populations of planet-forming disks show the same mass distribution at a given age. And they seem to be evolving in more or less the same way”, van Terwisga concludes. The result may even hint at the formation of stunningly similar planetary systems.

- As a next step, the scientists will look at possible impacts from nearby stars on smaller scales of a few light-years. While they avoided the strong radiation field caused by the massive stars in the ONC, there are potentially fainter field stars that may affect the dust in neighbouring disks and alter the disk mass statistics. Such contributions may explain some of the deviations found in the disk mass to age relation. The results can help strengthen the overall picture of a planet-forming disk evolution dominated by age.

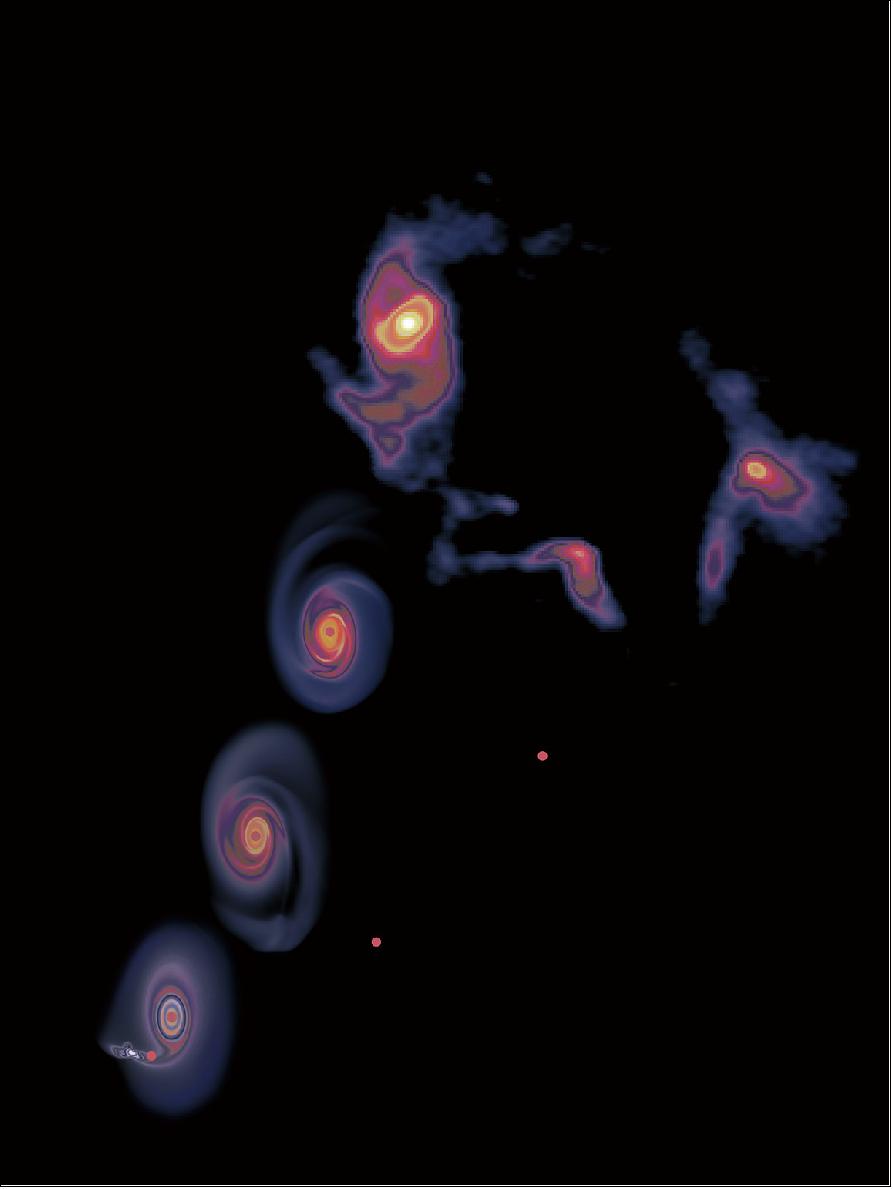

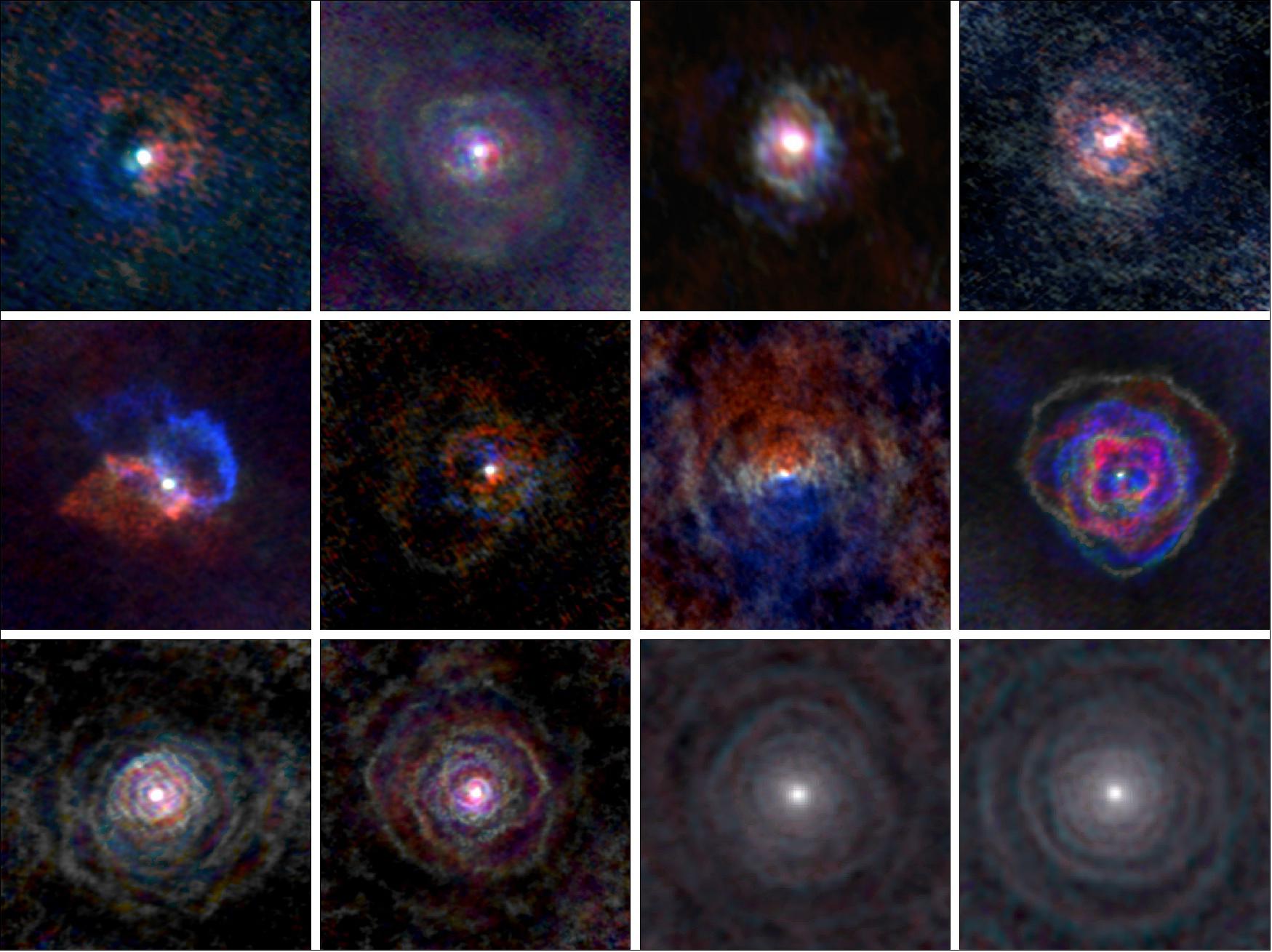

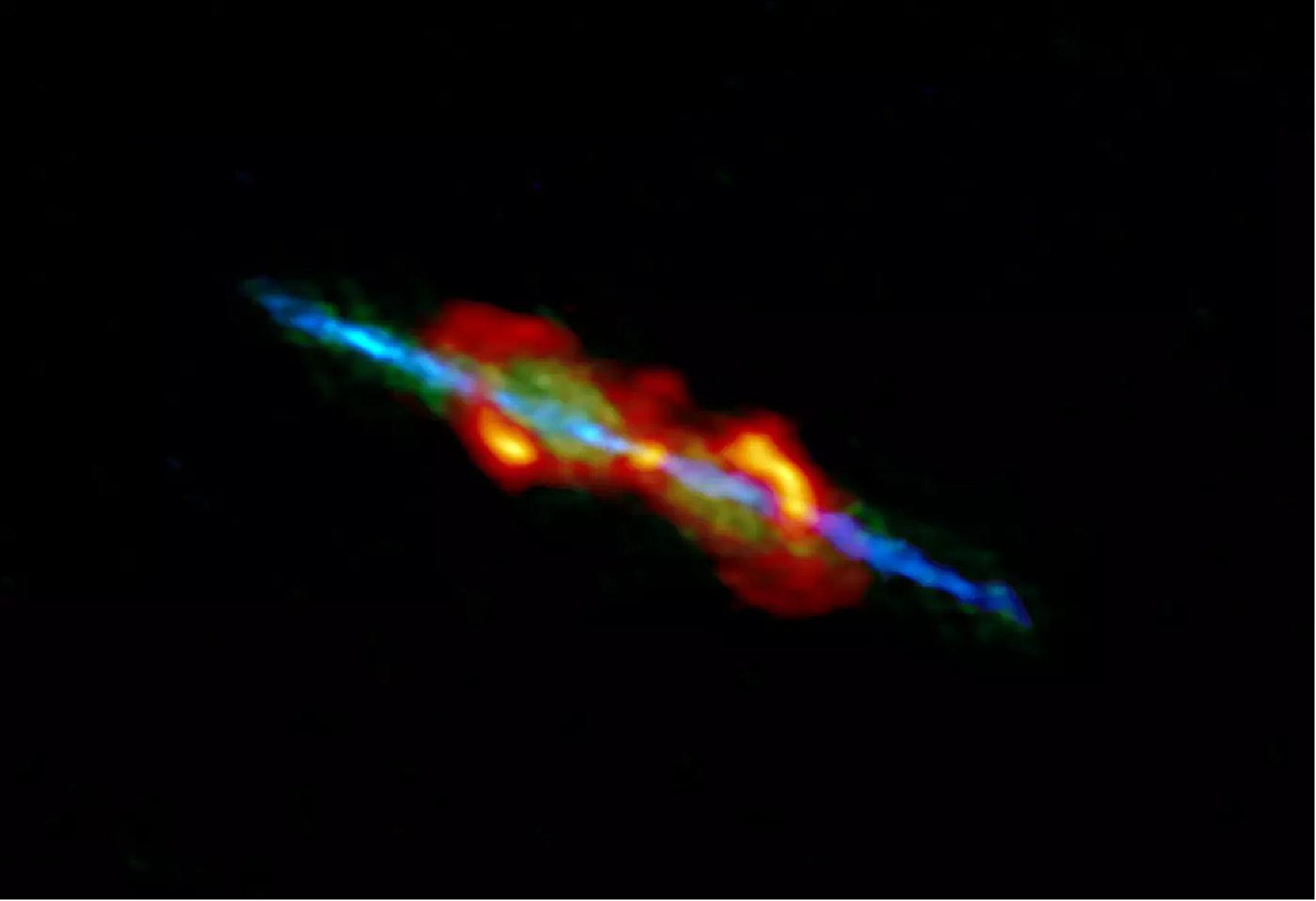

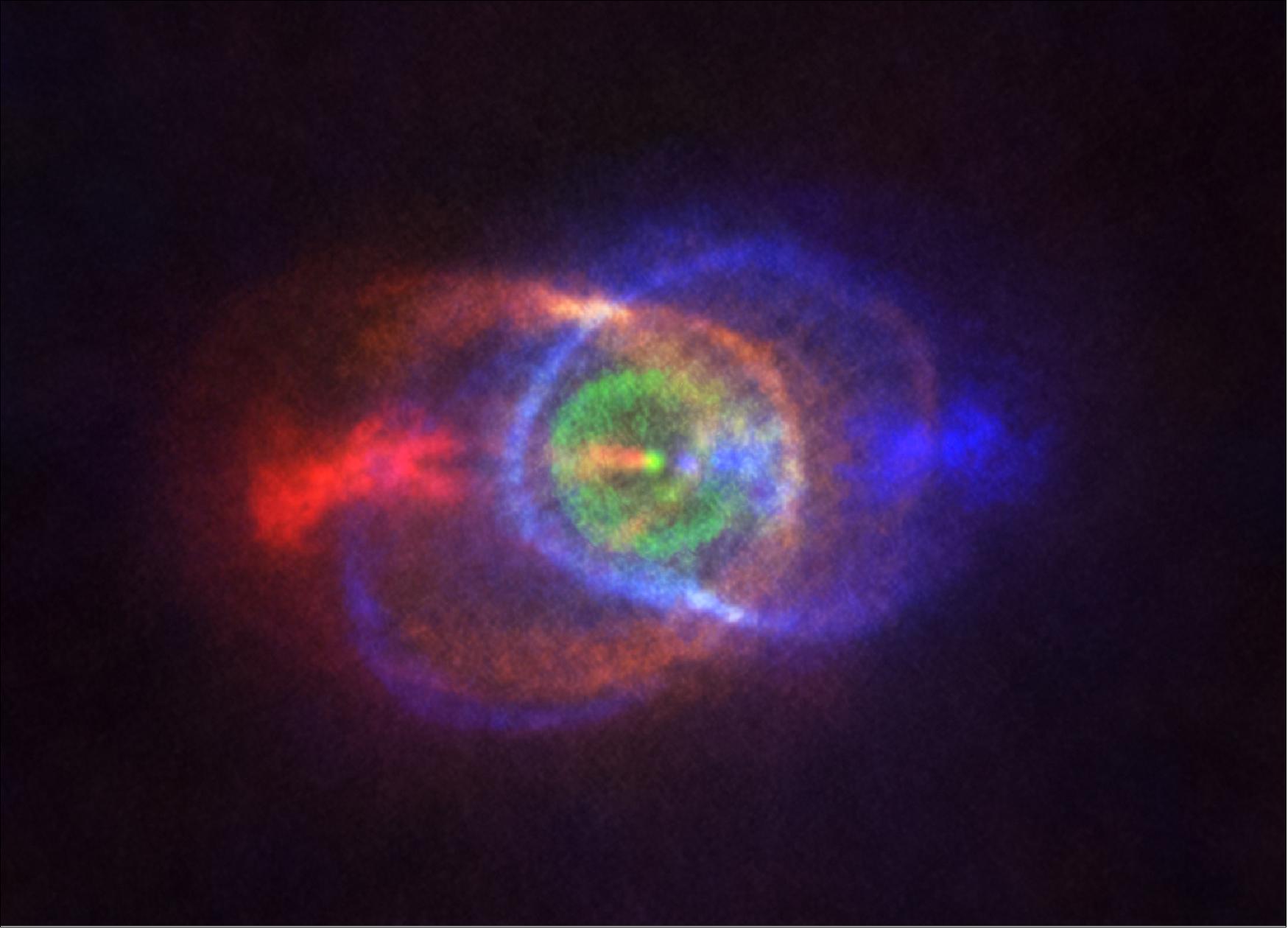

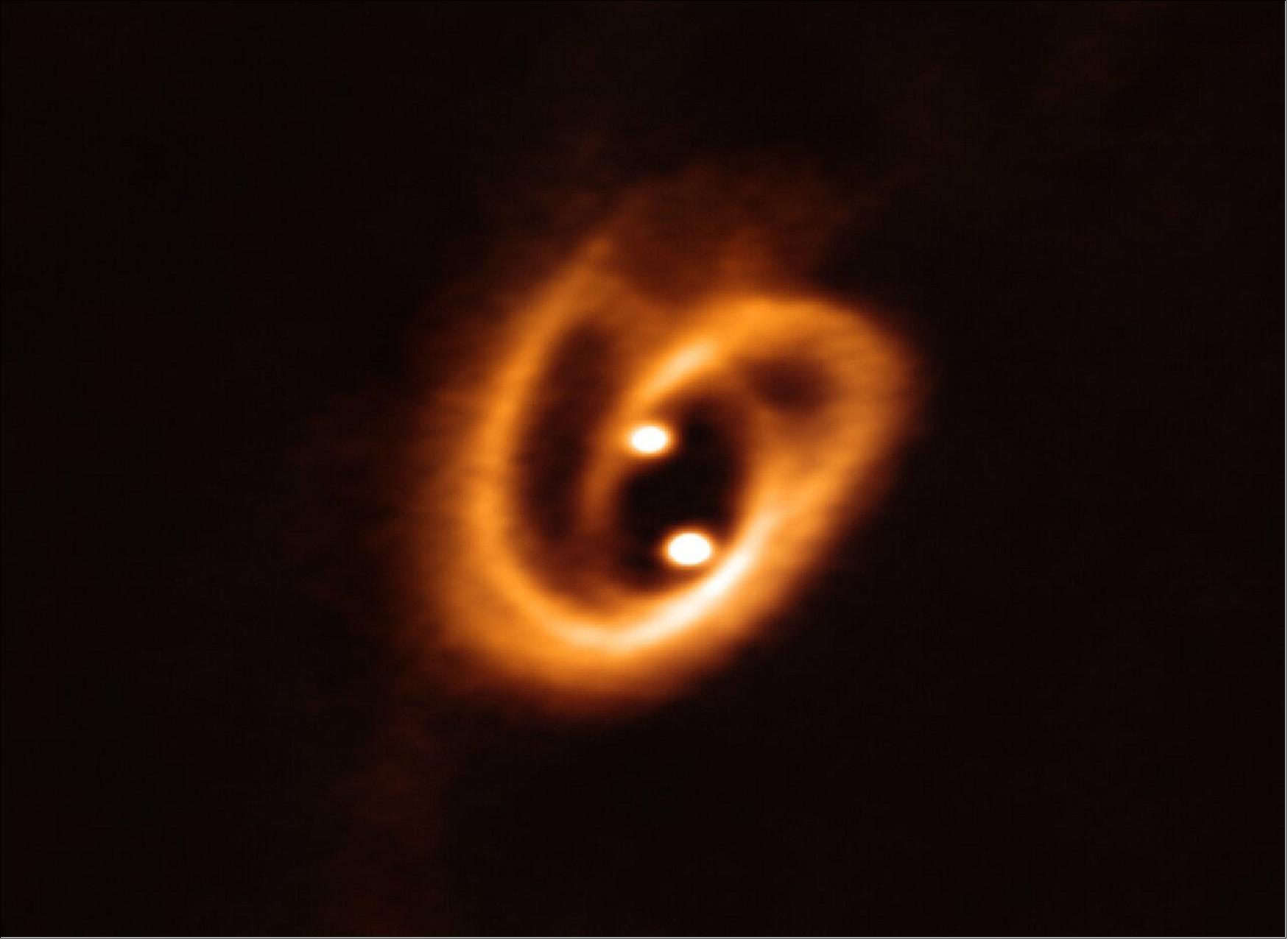

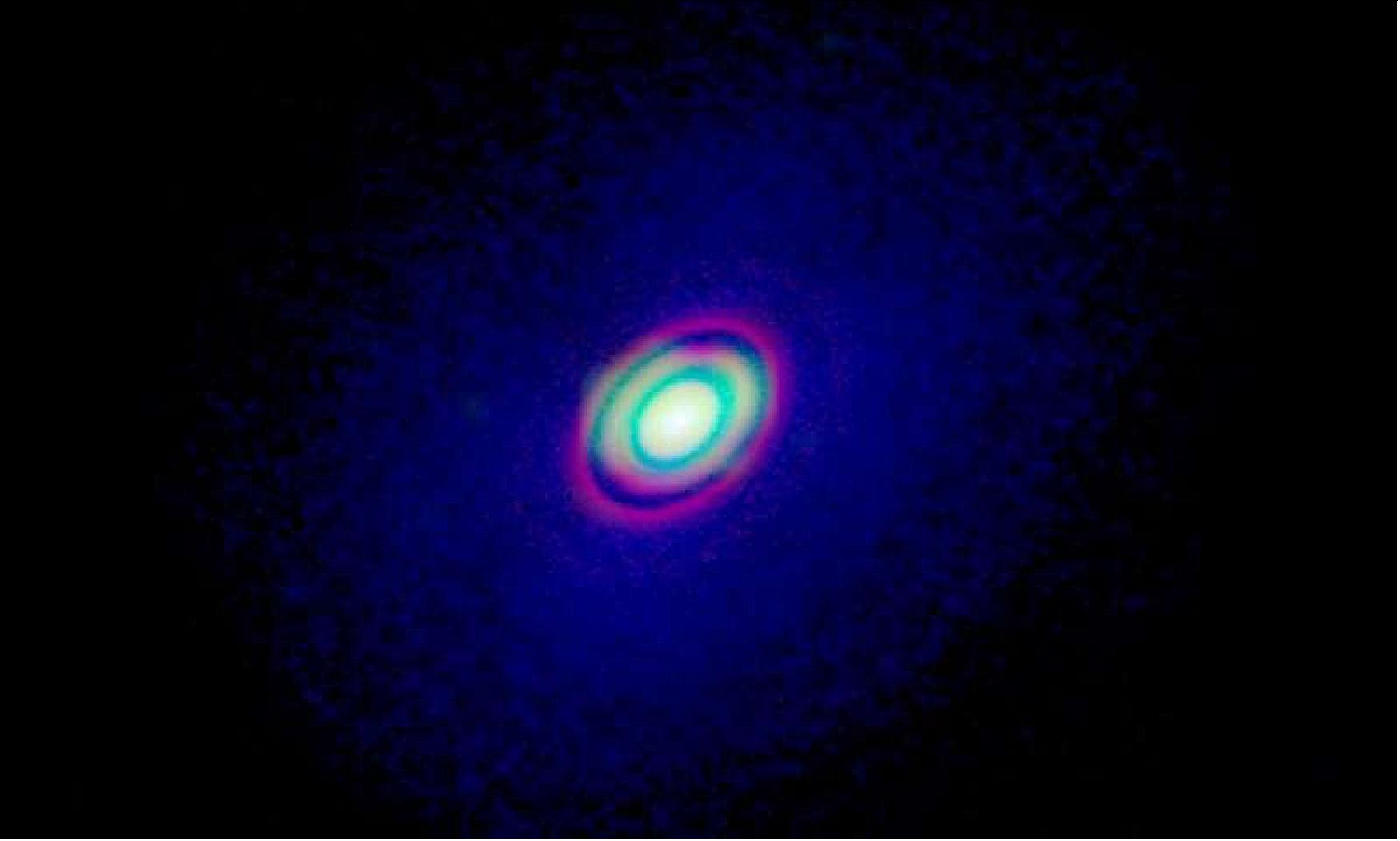

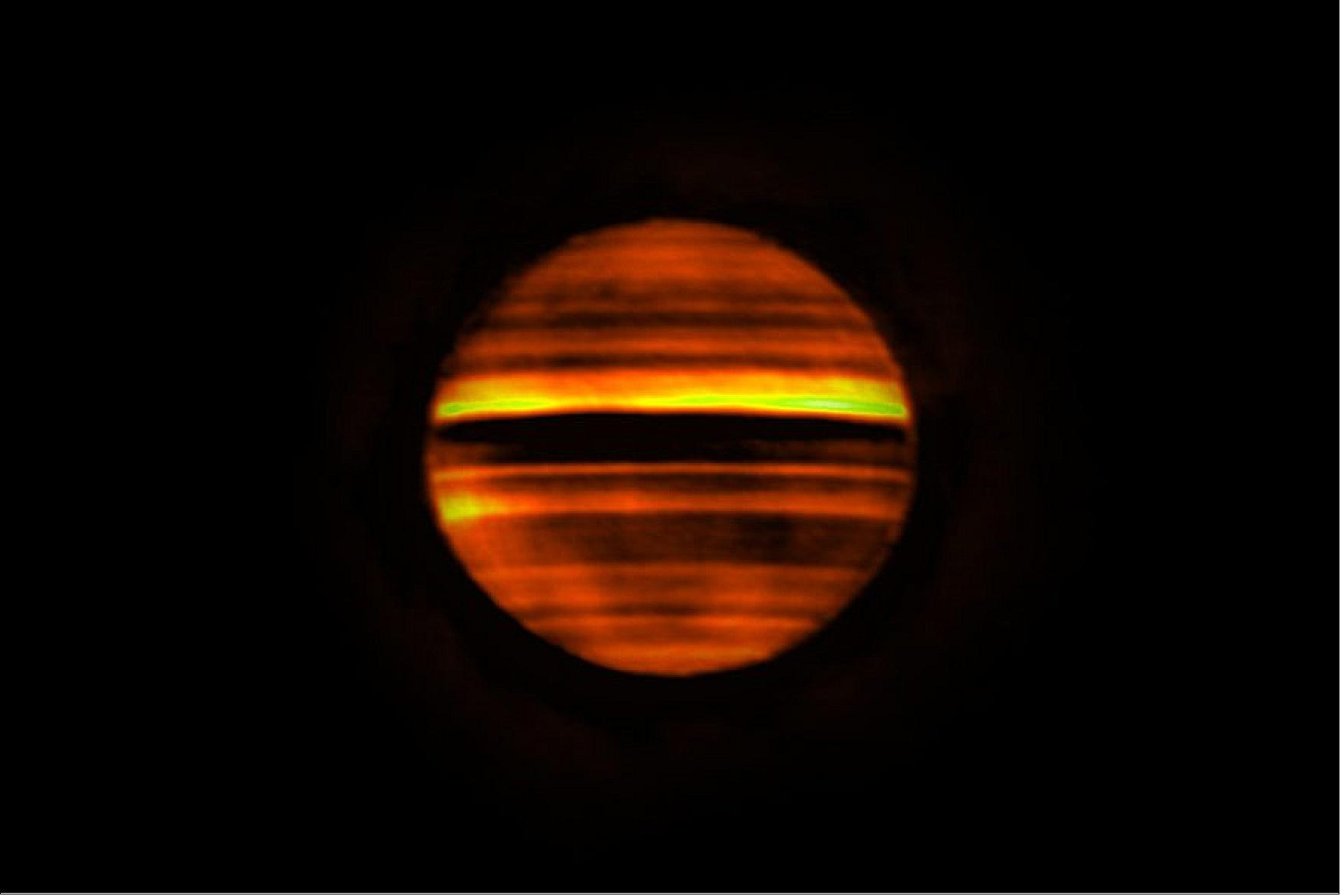

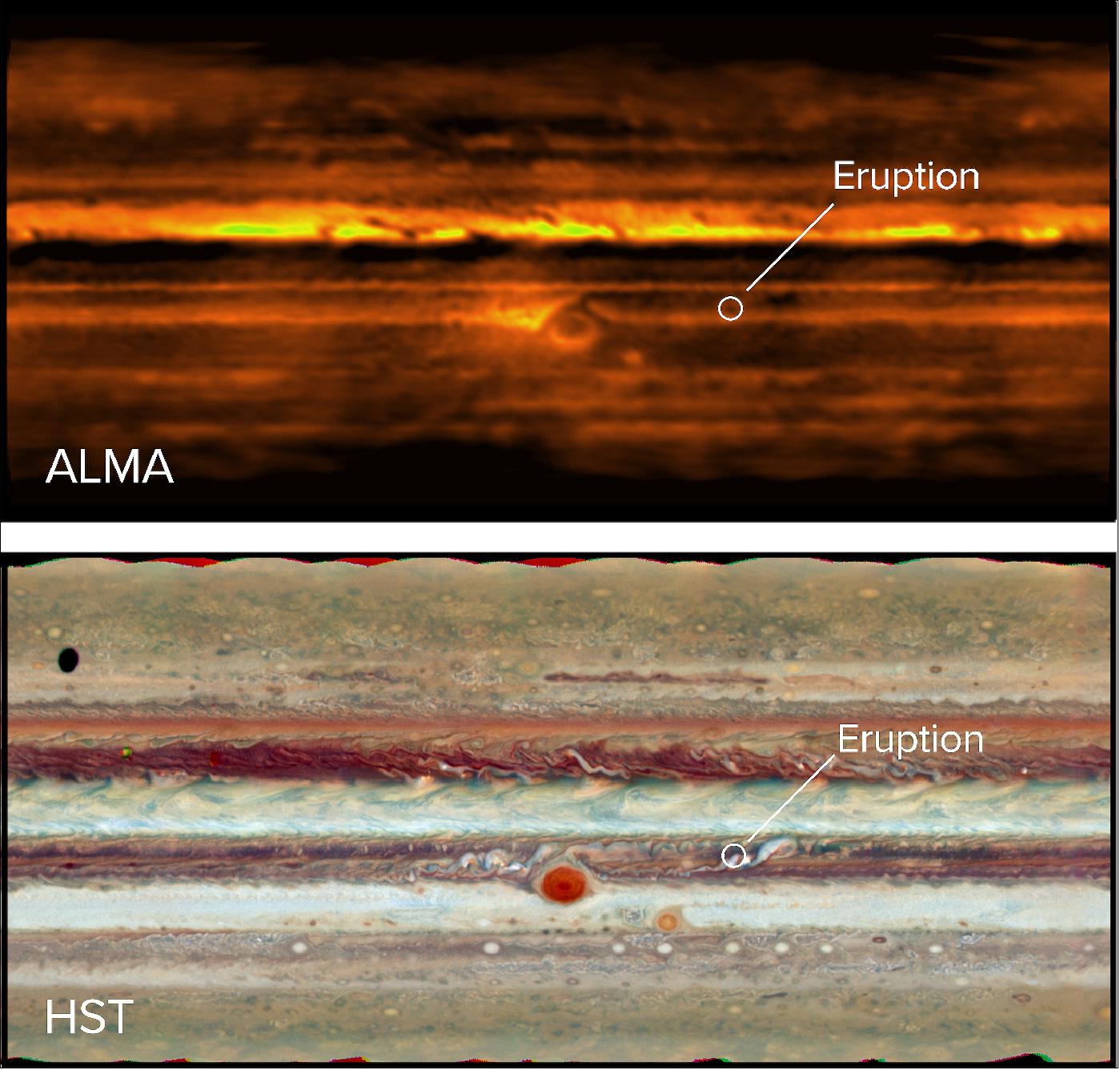

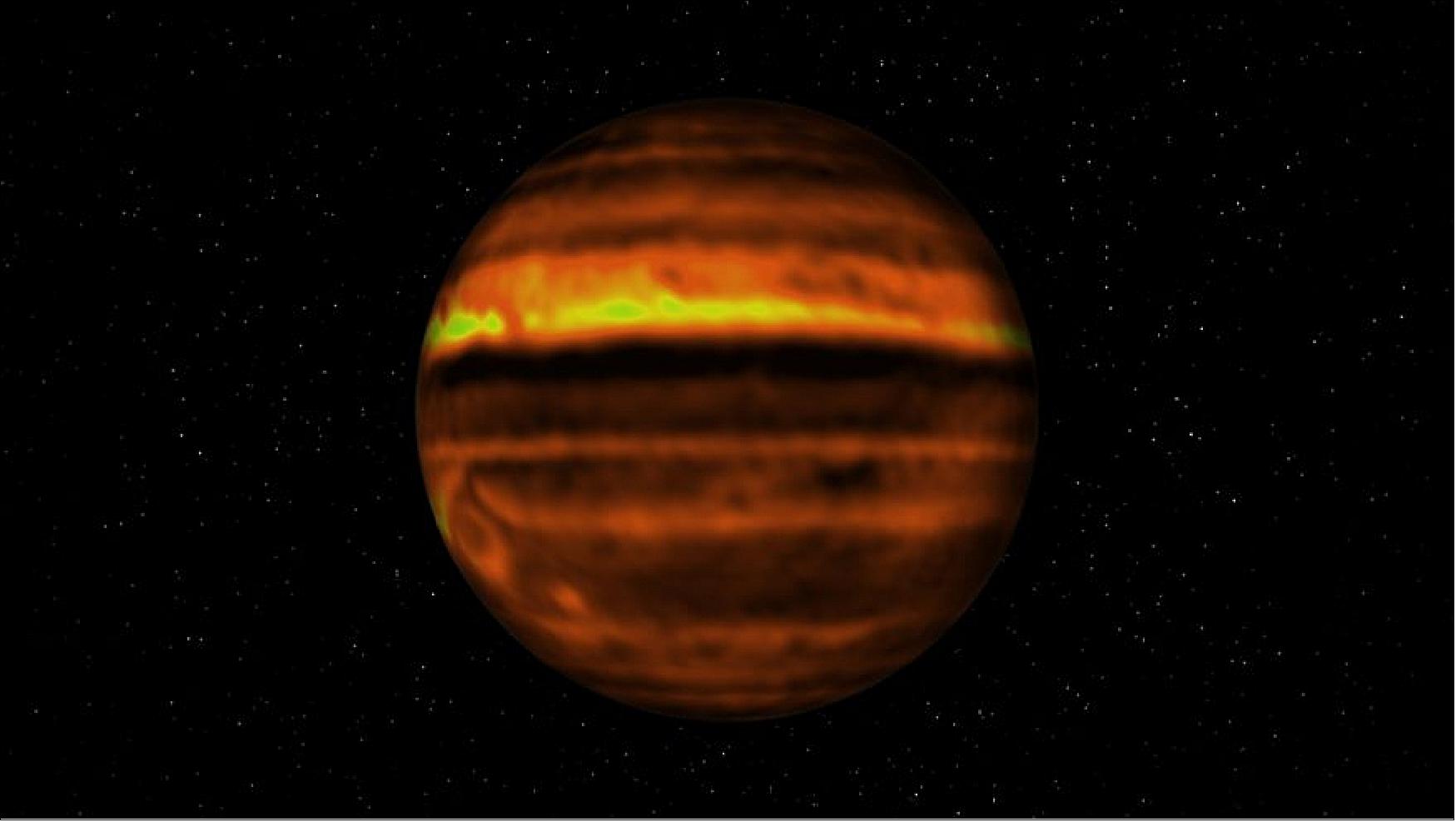

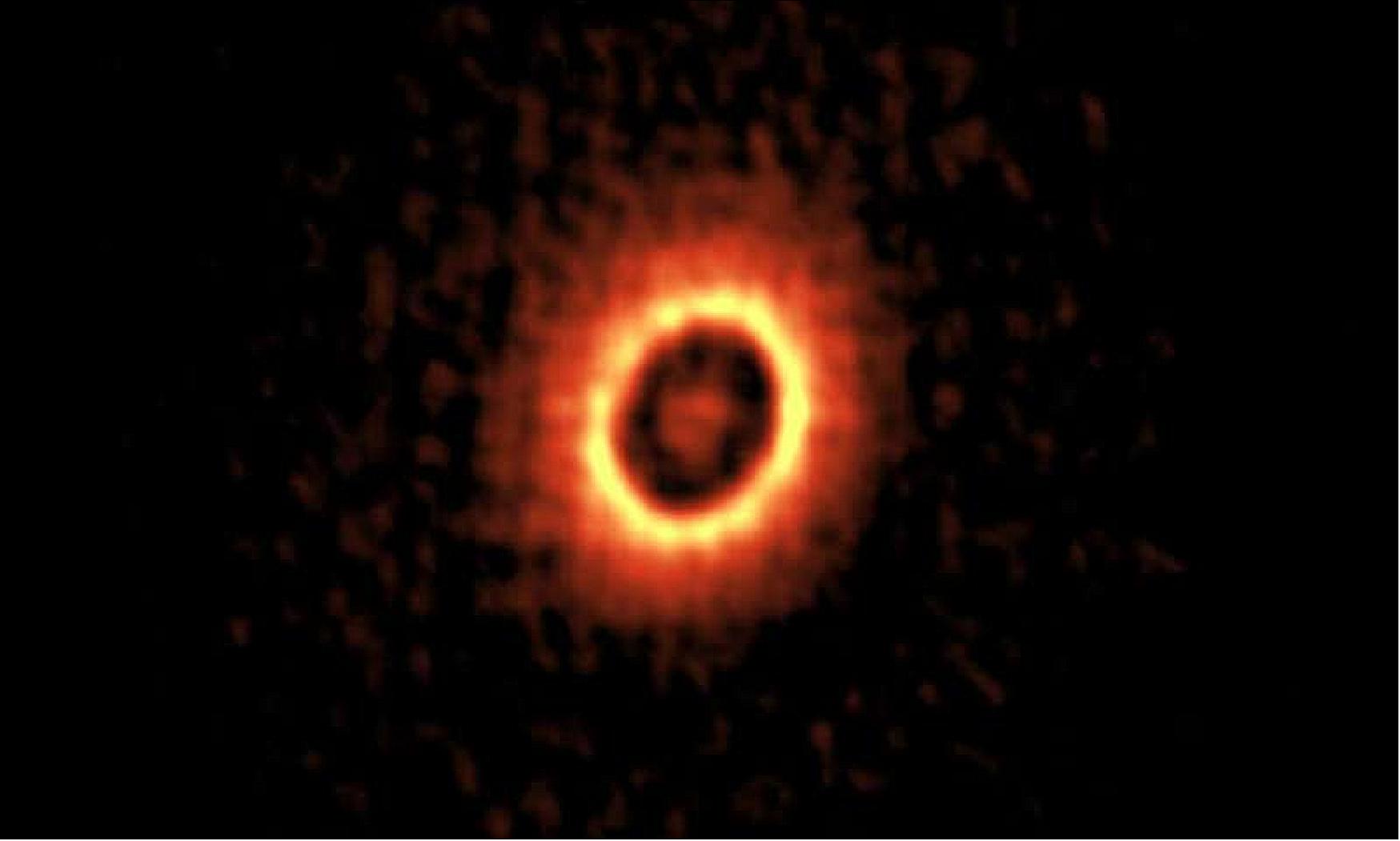

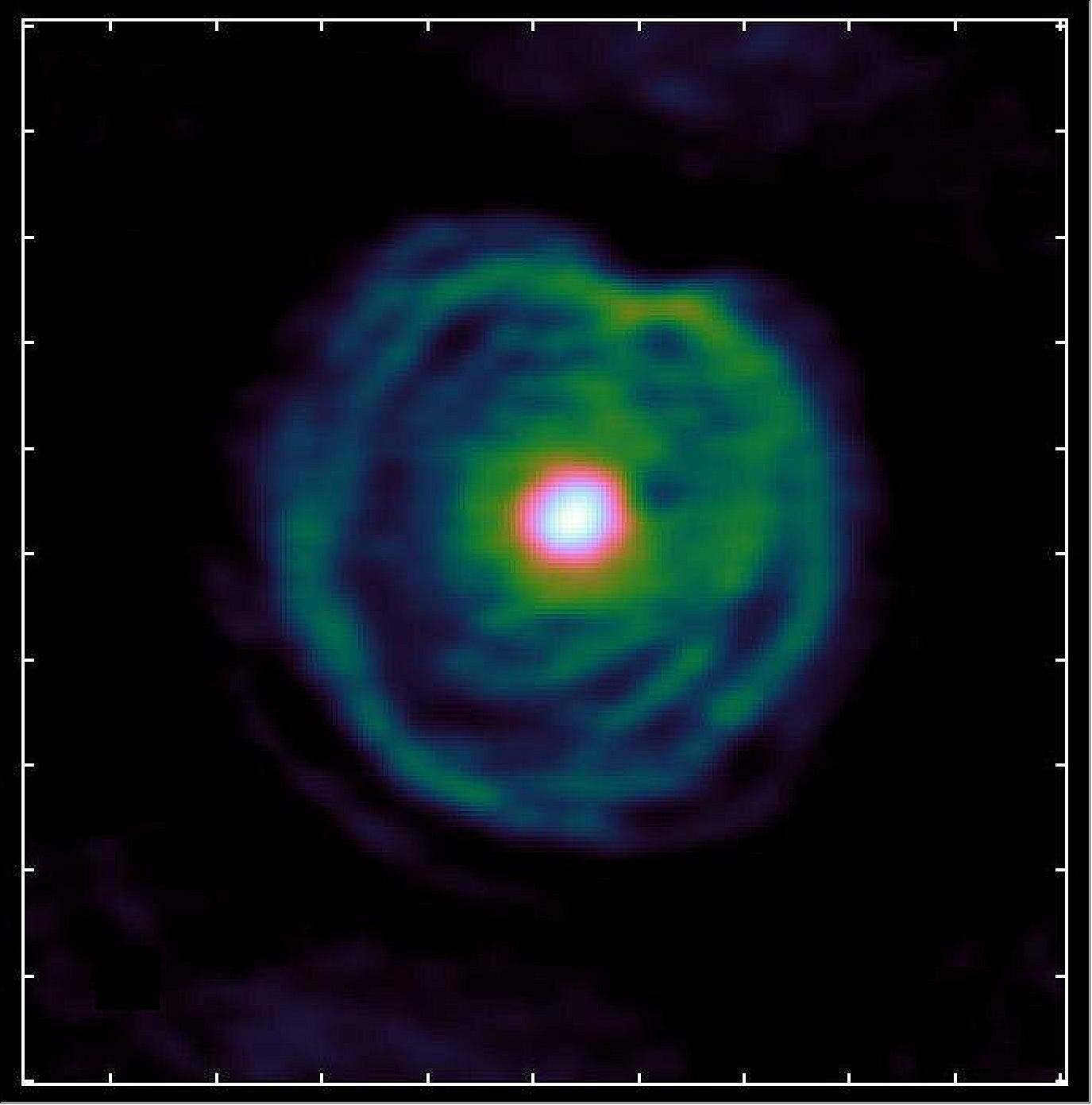

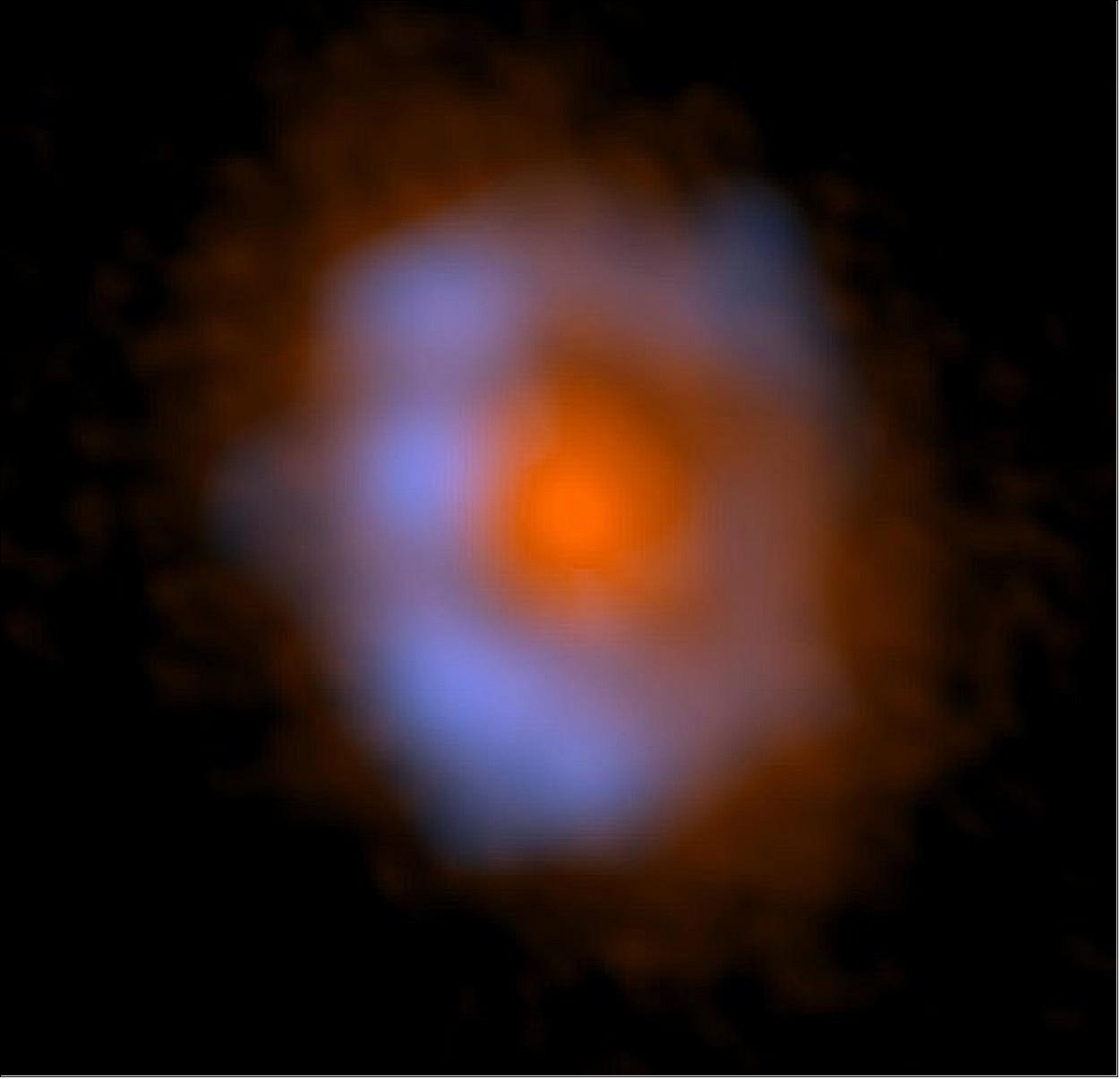

• March 28, 2022: Scientists studying V Hydrae (V Hya) have witnessed the star’s mysterious death throes in unprecedented detail. Using the Atacama Large Millimeter/submillimeter Array (ALMA) and data from the Hubble Space Telescope (HST), the team discovered six slowly-expanding rings and two hourglass-shaped structures caused by the high-speed ejection of matter out into space. The results of the study are published in The Astrophysical Journal. 40) 41) 42)

- V Hya is a carbon-rich asymptotic giant branch (AGB) star located approximately 1,300 light-years from Earth in the constellation Hydra. More than 90-percent of stars with a mass equal to or greater than the Sun evolve into AGB stars as the fuel required to power nuclear processes is stripped away. Among these millions of stars, V Hya has been of particular interest to scientists due to its so-far unique behaviors and features, including extreme-scale plasma eruptions that happen roughly every 8.5 years and the presence of a nearly invisible companion star that contributes to V Hya’s explosive behavior.

- “Our study dramatically confirms that the traditional model of how AGB stars die—through the mass ejection of fuel via a slow, relatively steady, spherical wind over 100,000 years or more—is at best, incomplete, or at worst, incorrect,” said Raghvendra Sahai, an astronomer at NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory, and the principal researcher on the study. “It is very likely that a close stellar or substellar companion plays a significant role in their deaths, and understanding the physics of binary interactions is both important across astrophysics and one of its greatest challenges. In the case of V Hya, the combination of a nearby and a hypothetical distant companion star is responsible, at least to some degree, for the presence of its six rings, and the high-speed outflows that are causing the star’s miraculous death.”

- Mark Morris, an astronomer at UCLA and a co-author on the research added, “V Hydra has been caught in the process of shedding its atmosphere—ultimately most of its mass—which is something that most late-stage red giant stars do. Much to our surprise, we have found that the matter, in this case, is being expelled as a series of outflowing rings. This is the first and only time that anybody has seen that the gas being ejected from an AGB star can be flowing out in the form of a series of expanding ‘smoke rings.’”

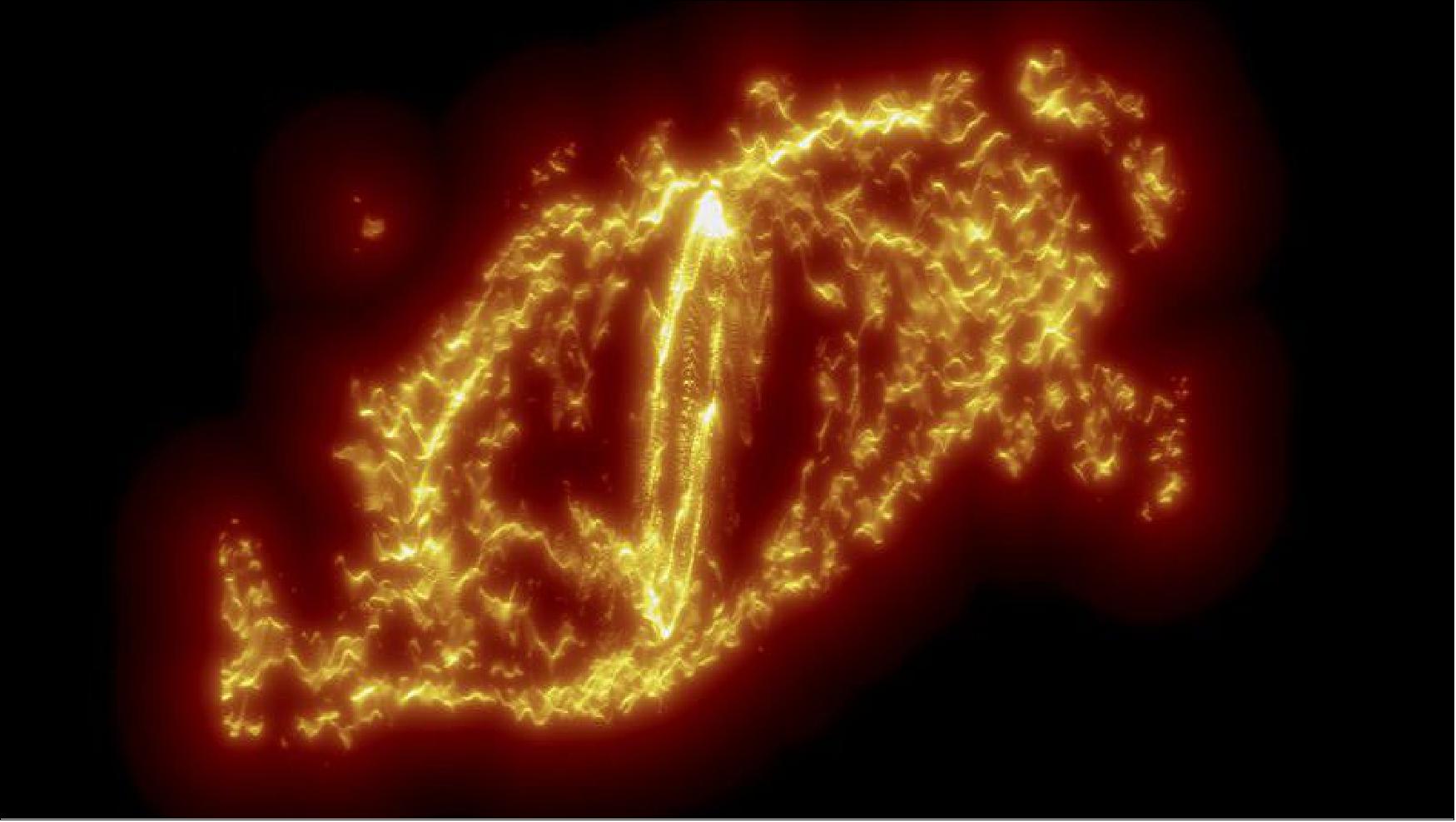

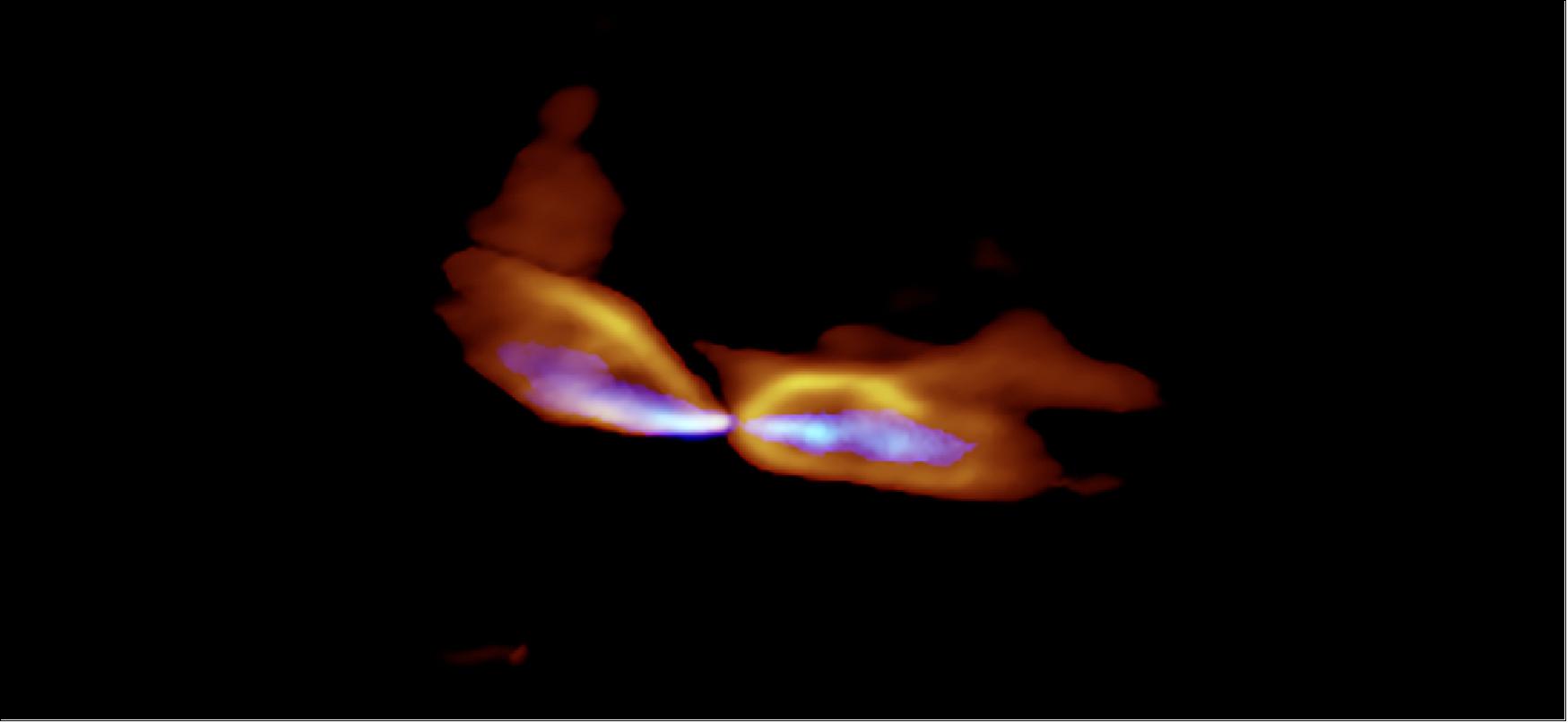

![Figure 27: The carbon-rich star V Hydrae is in its final act, and so far, its death has proved magnificent and violent. Scientists studying the star have discovered six outflowing rings (shown here in composite), and other structures created by the explosive mass ejection of matter into space [image credit: ALMA (ESO/NAOJ/NRAO)/S. Dagnello (NRAO/AUI/NSF)]](https://www.eoportal.org/ftp/satellite-missions/a/Alma_300622/Alma_Auto52.jpeg)

- The six rings have expanded outward from V Hya over the course of roughly 2,100 years, adding matter to and driving the growth of a high-density flared and warped disk-like structure around the star. The team has dubbed this structure the DUDE, or Disk Undergoing Dynamical Expansion.

- “The end state of stellar evolution—when stars undergo the transition from being red giants to ending up as white dwarf stellar remnants—is a complex process that is not well understood,” said Morris. “The discovery that this process can involve the ejections of rings of gas, simultaneous with the production of high-speed, intermittent jets of material, brings a new and fascinating wrinkle to our exploration of how stars die.”

- Sahai added, “V Hya is in the brief but critical transition phase that does not last very long, and it is difficult to find stars in this phase, or rather ‘catch them in the act. We got lucky and were able to image all of the different mass-loss phenomena in V Hya to better understand how dying stars lose mass at the end of their lives.”

- In addition to a full set of expanding rings and a warped disk, V Hya’s final act features two hourglass-shaped structures—and an additional jet-like structure—that are expanding at high speeds of more than half a million miles per hour (240 km/s). Large hourglass structures have been observed previously in planetary nebulae, including MyCn 18 —also known as the Engraved Hourglass Nebula—a young emission nebula located roughly 8,000 light-years from Earth in the southern constellation of Musca, and the more well-known Southern Crab Nebula, an emission nebula located roughly 7,000 light-years from Earth in the southern constellation Centaurus.

- In addition to a full set of expanding rings and a warped disk, V Hya’s final act features two hourglass-shaped structures—and an additional jet-like structure—that are expanding at high speeds of more than half a million miles per hour (240 km/s). Large hourglass structures have been observed previously in planetary nebulae, including MyCn 18 —also known as the Engraved Hourglass Nebula—a young emission nebula located roughly 8,000 light-years from Earth in the southern constellation of Musca, and the more well-known Southern Crab Nebula, an emission nebula located roughly 7,000 light-years from Earth in the southern constellation Centaurus.

- Sahai said, “We first observed the presence of very fast outflows in 1981. Then, in 2022, we found a jet-like flow consisting of compact plasma blobs ejected at high speeds from V Hya. And now, our discovery of wide-angle outflows in V Hya connects the dots, revealing how all these structures can be created during the evolutionary phase that this extra-luminous red giant star is now in.”

- Due to both the distance and the density of the dust surrounding the star, studying V Hya required a unique instrument with the power to clearly see matter that is both very far away and also difficult or impossible to detect with most optical telescopes. The team enlisted ALMA’s Band 6 (1.23 mm) and Band 7 (.85 mm) receivers, which revealed the star’s multiple rings and outflows in stark clarity.

- “The processes taking place at the end stages of low mass stars, and during the AGB phase in particular, have long fascinated astronomers and have been challenging to understand,” said Joe Pesce, an astronomer and NSF program officer for NRAO/ALMA. “The capabilities and resolution of ALMA are finally allowing us to witness these events with the extraordinary detail necessary to provide some answers and enhance our understanding of an event that happens to most of the stars in the Universe.”