Hayabusa-2 (Japan's Second Asteroid Sample Return Mission)

Non-EO

JAXA

Quick facts

Overview

| Mission type | Non-EO |

| Agency | JAXA |

| Launch date | 03 Dec 2014 |

| End of life date | 05 Dec 2020 |

Hayabusa-2: Japan's Second Asteroid Sample Return Mission

Spacecraft Launch Mission Status Sensor Complement MASCOT Sample Return Capsule References

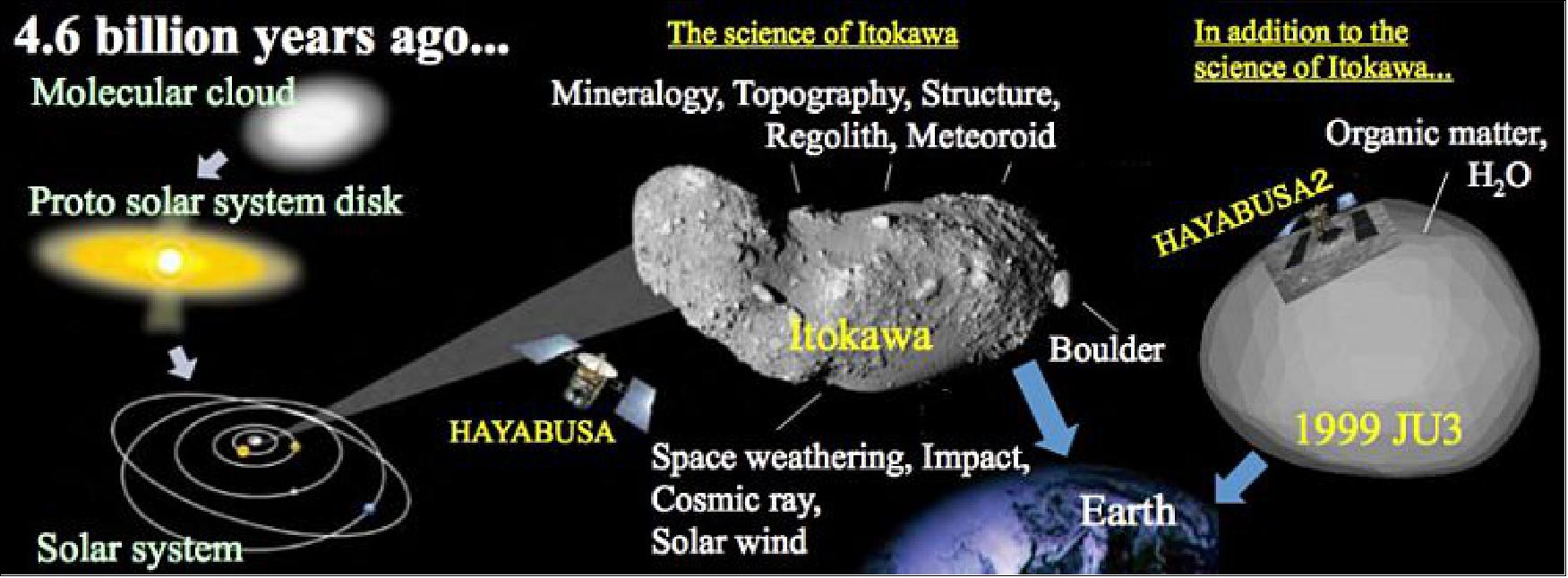

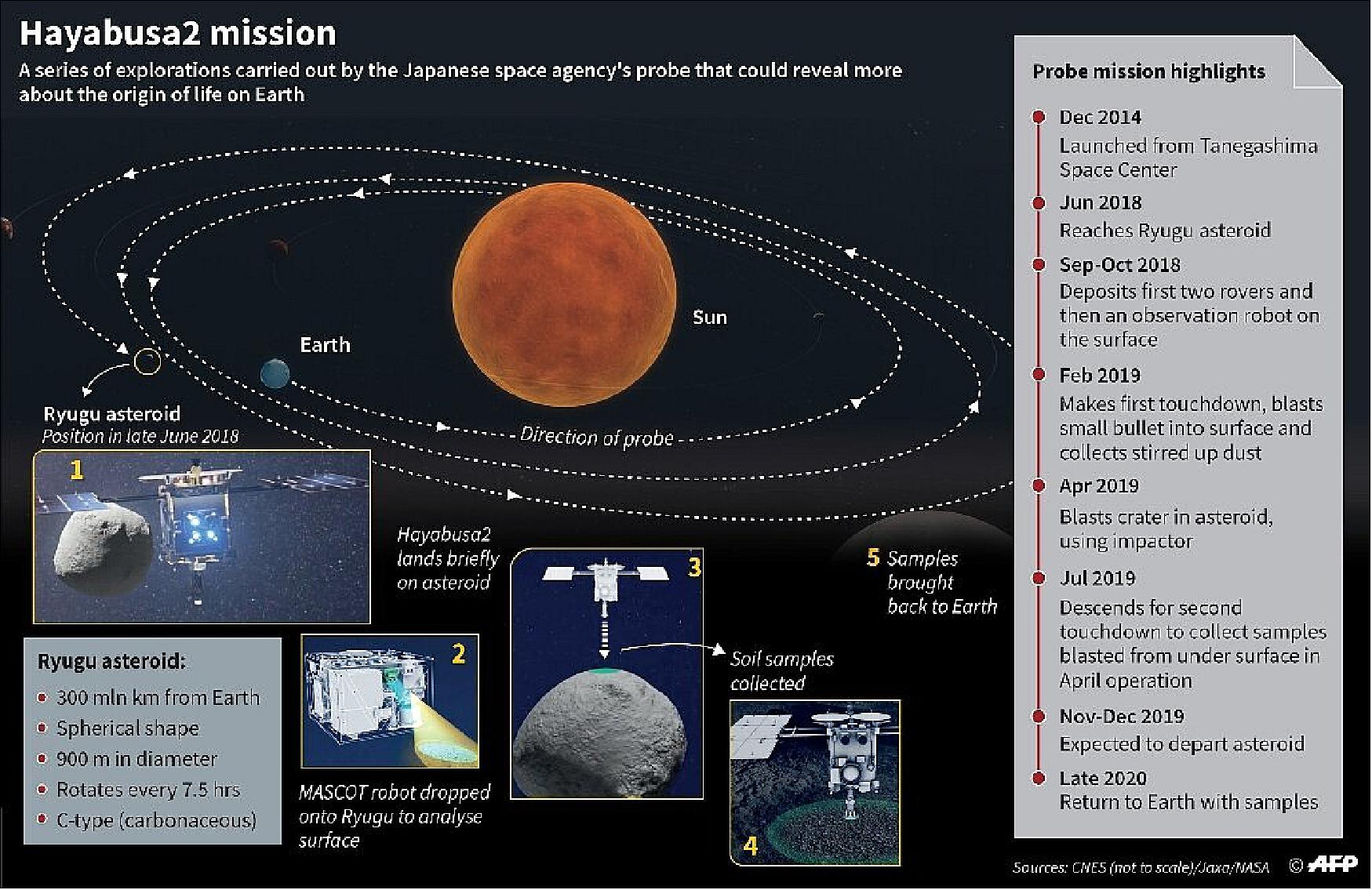

Hayabusa-2 is JAXA's (Japan Aerospace Exploration Agency) follow-on mission to the Hayabusa mission, the country's first round-trip asteroid mission that sent the Hayabusa (MUSES-C) spacecraft to retrieve samples of asteroid Itokawa. The initial Hayabusa mission launched in May 2003 and reached Itokawa in 2005; it returned samples of Itokawa — the first asteroid samples ever collected in space — in June 2010. Hayabusa means 'falcon' in Japanese. 1) 2) 3) 4)

The objective of the Hayabusa-2 sample return mission is to visit and explore the C-type asteroid 1999 JU3, a space body of about 920 m in length and of particular interest to researchers, because it consists of 4.5 billion-year-old material that has been altered very little. Measurements taken from Earth suggest that the asteroid’s rock may have come into contact with water. The carbonaceous or C-type asteroid is expected to contain organic and hydrated minerals, making it different from Itokawa, which was a rocky S-type (stony composition) asteroid.

Background

Primitive bodies are celestial bodies which contain information of the birth or the following evolution of our solar system. In larger bodies such as the Earth, the pristine materials inside were once melted and we cannot access older information. On the other hand, hundreds of thousands of asteroids and comets discovered ever, though they are very small, retain memories of when and where they were formed in the solar system. Exploration of such primitive bodies will provide us an essential clue for how our solar system was formed and has grown, and how the primary organic materials of life on the Earth were composed and evolved, which will be important knowledge also in investigating formation and evolution of exoplanets.

Among primitive bodies, asteroids can be classified into several groups according to the spectroscopic observation by telescopes. Inside the asteroid belt between the Mars and Jupiter, it is known that distribution of each group varies according to the distance from the Sun.

In the region close to the Sun, we can observe many 'S-type asteroids' whose primary component is expected to be stony. These will give us hints about components of stony planets such as the Earth and Mars. S-type asteroids have been expected to be the birthplace of 'ordinary chondrite', the most common meteorites on the Earth. This hypothesis was extensively confirmed by exploration of S-type asteroid "Itokawa" by JAXA's asteroid probe Hayabusa.

Most commonly distributed around the midst of the asteroid belt are 'C-type asteroids' expected to contain substantial organic or hydrated minerals. This type is expected to be the birthplace of 'carbonaceous chondrite', and an important target for investigation of origin of life on earth. The Hayabusa-2 mission, following Hayabusa, is planning a sample-return from C-type asteroids.

Around the dark and cold outer edge of the belt, closer to Planet Jupiter rather than to Mars, there are many P-type or D-type asteroids, expected to be more primitive than the S- or C-type ones. Trojan groups sharing their orbits with Jupiter are repositories of D-type asteroids. Active comets abundant in volatile components, born in further space and changed its orbit relatively recently to come closer to the Sun, or "dormant comet nuclei" depleting gases or dusts and difficult to distinguish from asteroids, are also quite essential targets. Because meteorites from D-, P-type asteroids or comet nuclei have been scarcely discovered on the Earth, the surface materials and constructions of these distant bodies are entirely unknown. Materials yet to be acquired, holding the earliest information at the birth of the solar system, may be discovered. The successive mission after "Hayabusa-2" is discussed to fetch samples from such bodies.

In this respect, JAXA will conduct, not only random single missions, but programmatic and systematic mission series successively, by Hayabusa, Hayabusa-2 and post -Hayabusa-2 for sample-return from typical primitive bodies. This will allow a unified understanding of various primitive bodies, revealing of components and construction of the whole solar system, and elucidation of the mystery behind its origin and evolution. This successive sequence is directed to the more distant and more primitive bodies from the scientific view, with more sophisticated technologies.

Overview

Hayabusa →Visit to S-type Asteroid | Hayabusa-2 →Visit to C-type Asteroid |

Technological demonstrator: | 1) Science: |

Engineering: | 2) Engineering: |

Science: Origin and evolution of the solar system | 3) Exploration: |

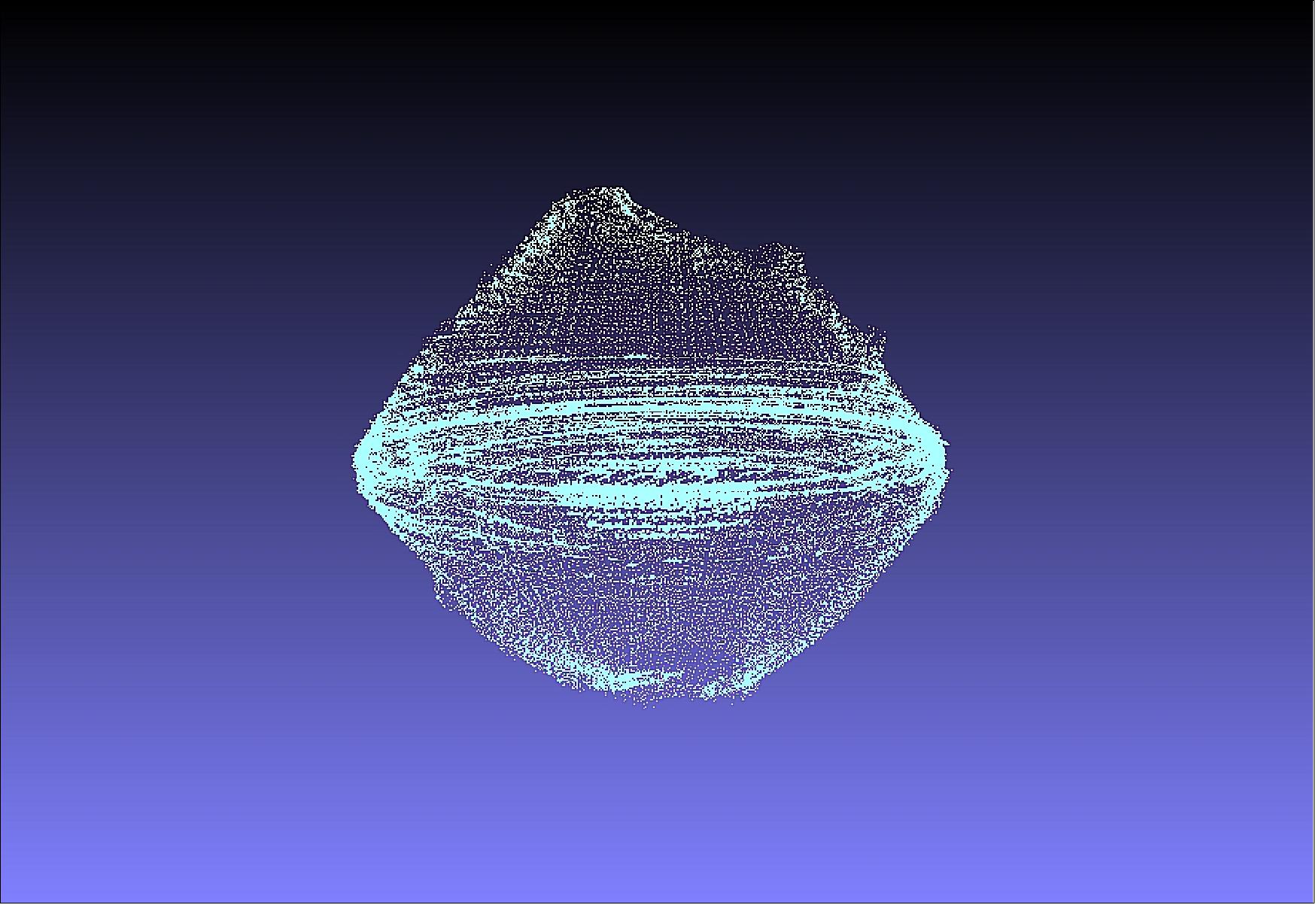

Detailed information of asteroid 1999JU3 has been obtained by observations of ground-based telescopes. According to observation data of 2008, the diameter of 1999JU3 is estimated to be about 900 m, larger than that Itokawa, and the rotation period is around 7.6 hours. Observation of the reflected sunlight spectrum showed, that it has features of a C-type asteroid. It is rather difficult to determine the spin axis of asteroid 1999JU3 because of its rather spherical shape.

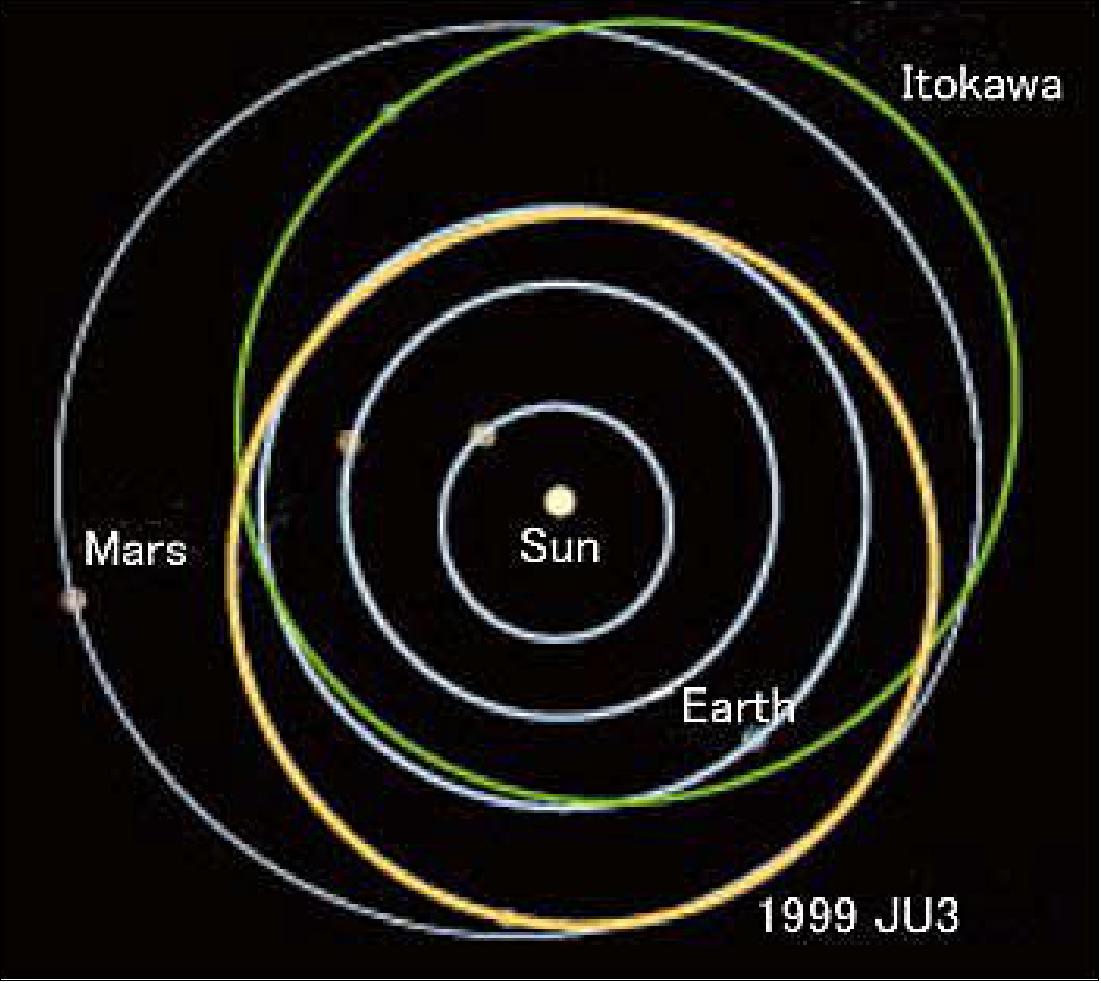

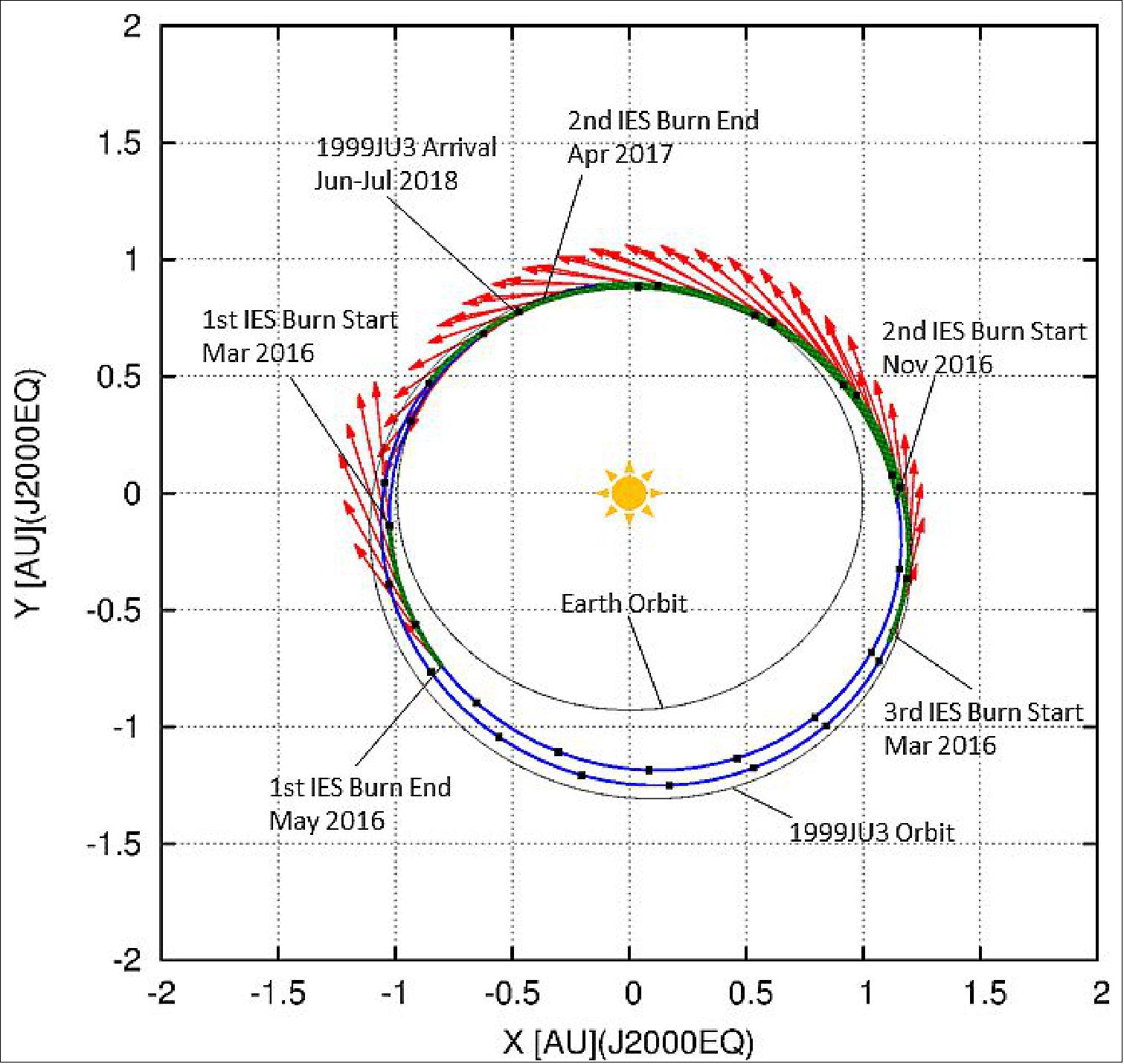

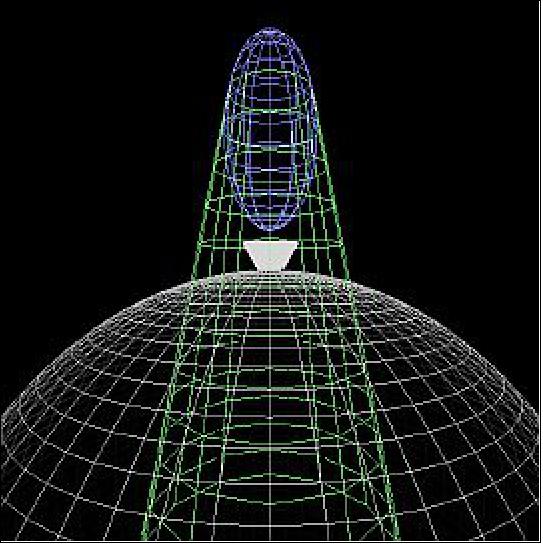

Figure 2 shows the orbit of asteroid 1999 JU3. The orbit is similar to that of Itokawa, and it is orbiting from just inside the orbit of the Earth to just outside the orbit of Mars. The inclination of the orbit is small like the one of Itokawa. Such an orbit is suitable for a small spacecraft like Hayabusa-2 to reach and return to Earth.

Legend to Figure 2: The blue circled lines in the figure illustrate the orbits of Mercury, Venus, Earth and Mars from inside, respectively, Itokawa's orbit is green, while the yellow orbit is that of 1999JU3.

The asteroid was discovered in 1999 by the LINEAR (Lincoln Near-Earth Asteroid Research) project, and given the provisional designation 1999JU3 (it hasn't been named so far). LINEAR is a collaboration of the United States Air Force, NASA, and MIT/LL (Massachusetts Institute of Technology /Lincoln Laboratory) for the systematic discovery and tracking of near-Earth asteroids.

Project History

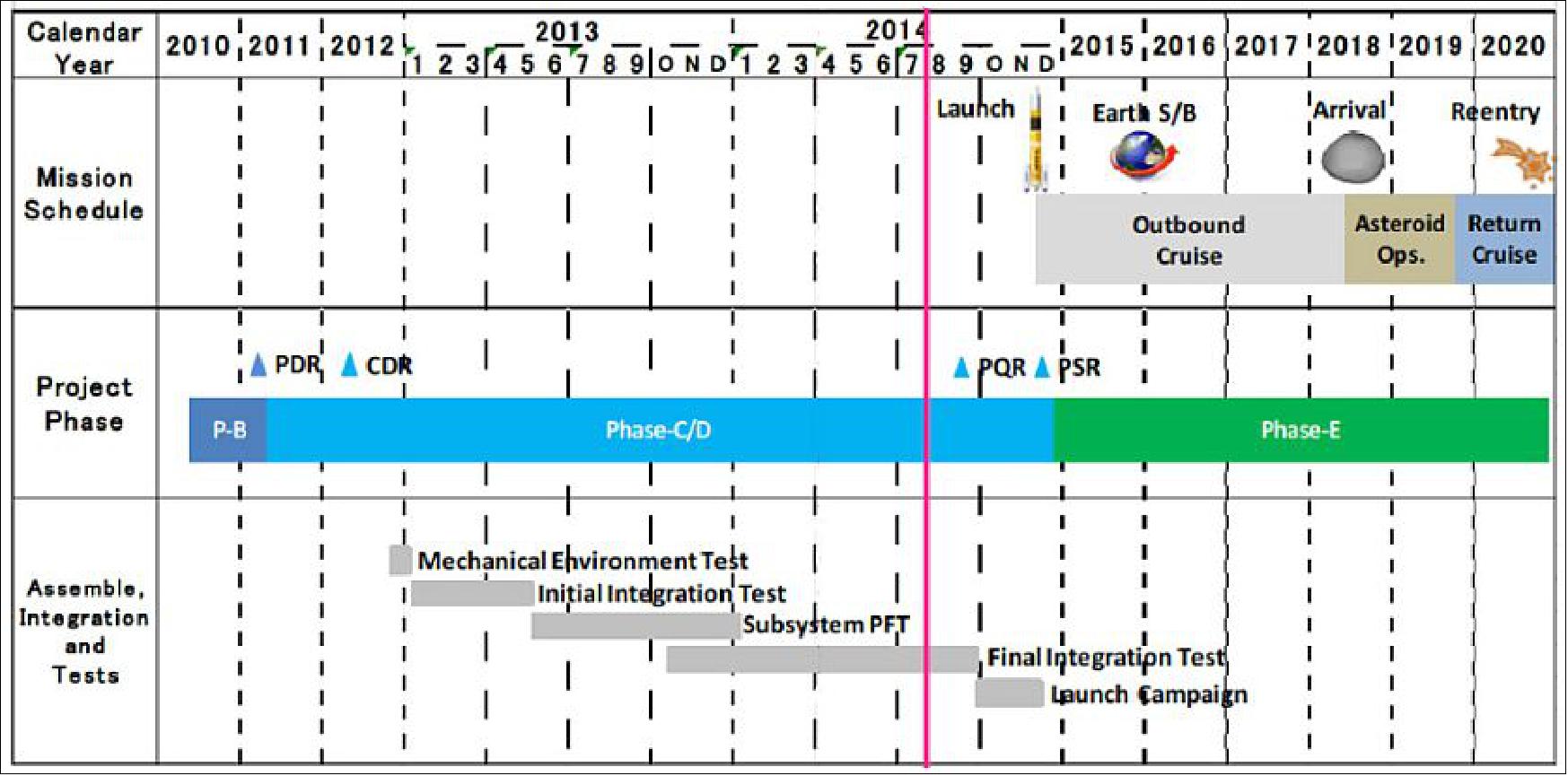

The Hayabusa-2 mission was proposed in 2006 at first. In this first proposal, the spacecraft was almost same as that of Hayabusa, because the project team wanted to start it as soon as possible. Of course, the team realized that parts had to be modified where trouble occurred in Hayabusa, but there were no major changes. The launch windows to go for launch to asteroid 1999 JU3 were in 2010 and 2011. However, JAXA could not start Hayabusa-2 mission immediately, because no budget was available. Hence, the launch opportunity was missed. The next launch window came up in 2014. Thus, the project postponed the launch date, and continued proposing Hayabusa-2. Since the launch was delayed, the project had time to change the spacecraft a little. New instruments were added, such as a Ka-band antenna and what is called “impactor.” The project even calls Hayabusa-2 a new spacecraft. 6)

In May 2011, the status of Hayabusa-2 project shifted to Phase-B, starting with the design of the spacecraft. In March 2012, the CDR (Critical Design Review) was done, and the team started manufacturing the flight model. The initial integration test started at the beginning of 2013, and the final integration test started at the end of 2013. At present (September 2014), the team has almost finished the final integration test, and the spacecraft will be shipped to the launch site soon.

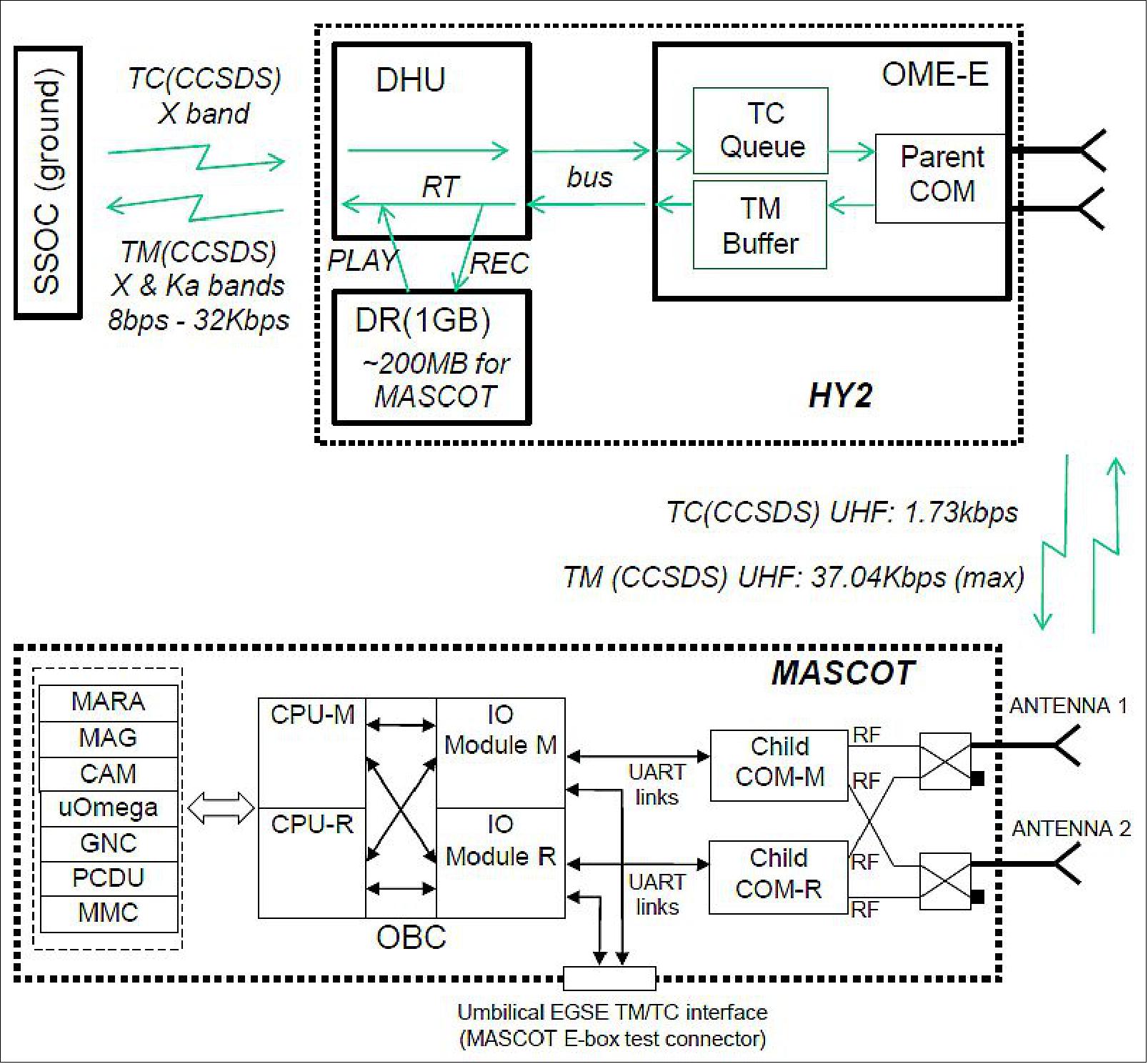

International collaborations: The Hayabusa-2 mission involves international collaborations with Germany, the United States, and Australia. DLR (German Aerospace Center) and CNES (French Space Agency) are providing the small lander MASCOT. NASA was already a partner in the Hayabusa mission, a similar collaboration is under consideration for Hayabusa-2. The third collaboration is with Australia for capsule reentry as in the case of the Hayabusa mission.

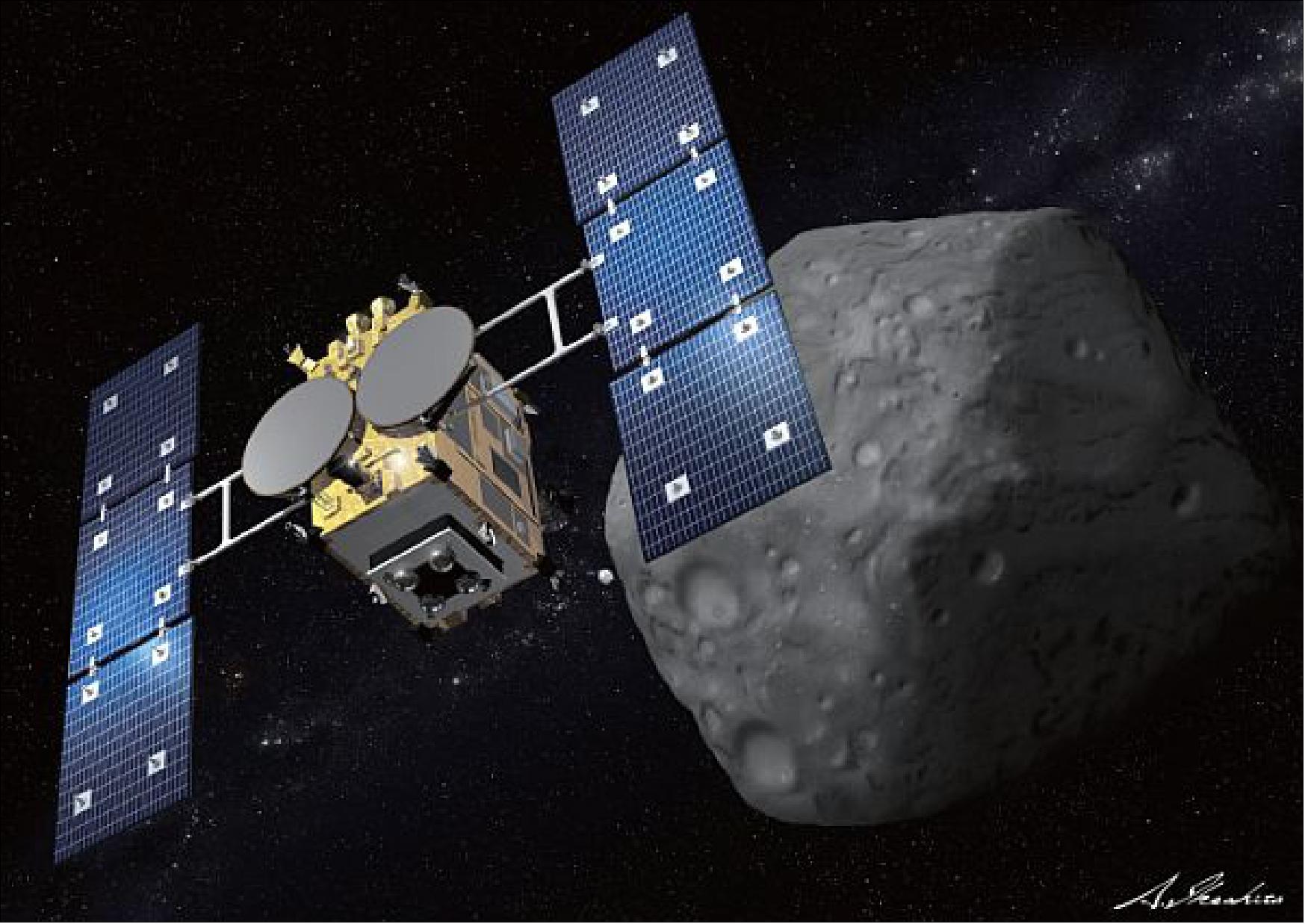

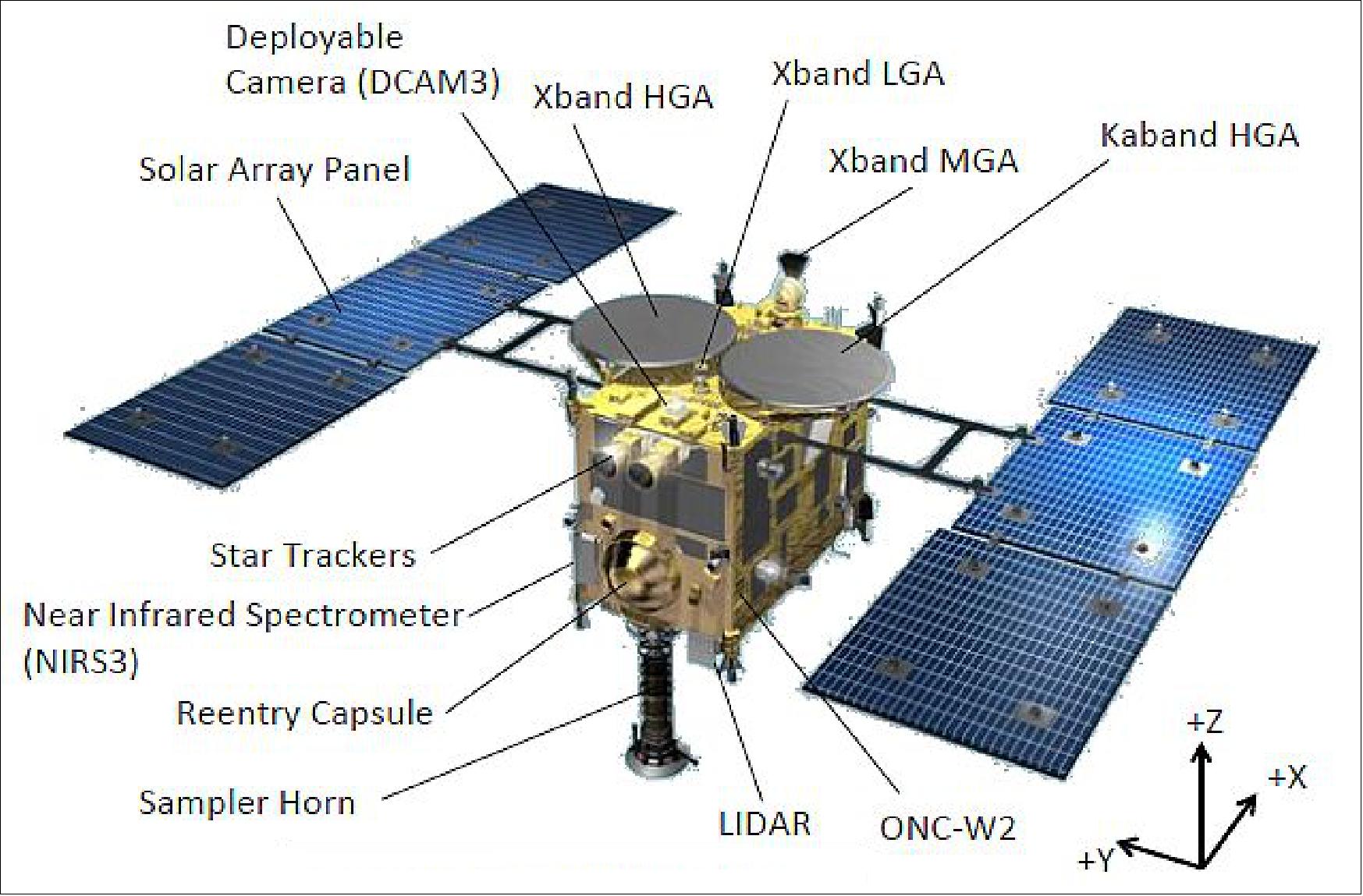

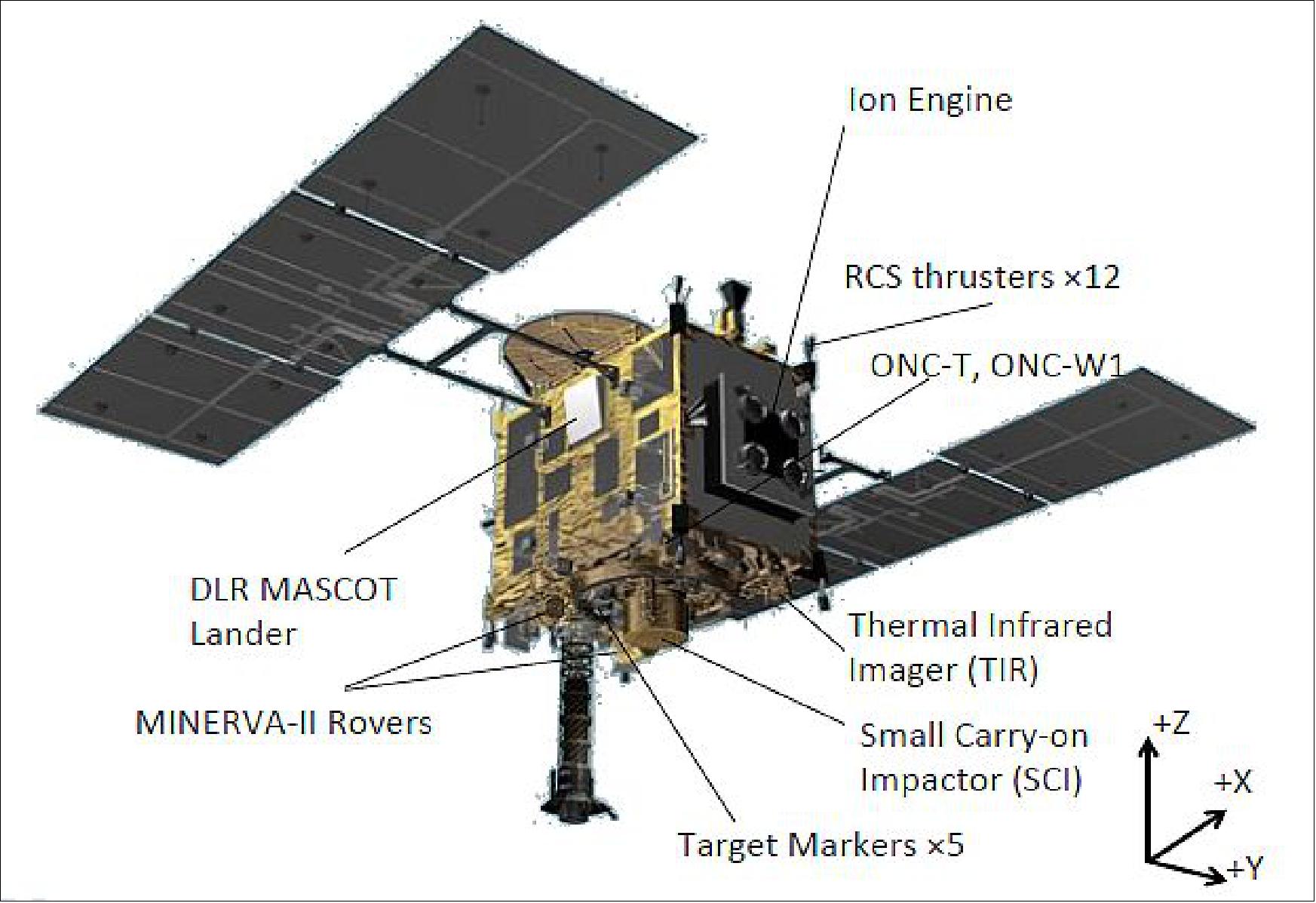

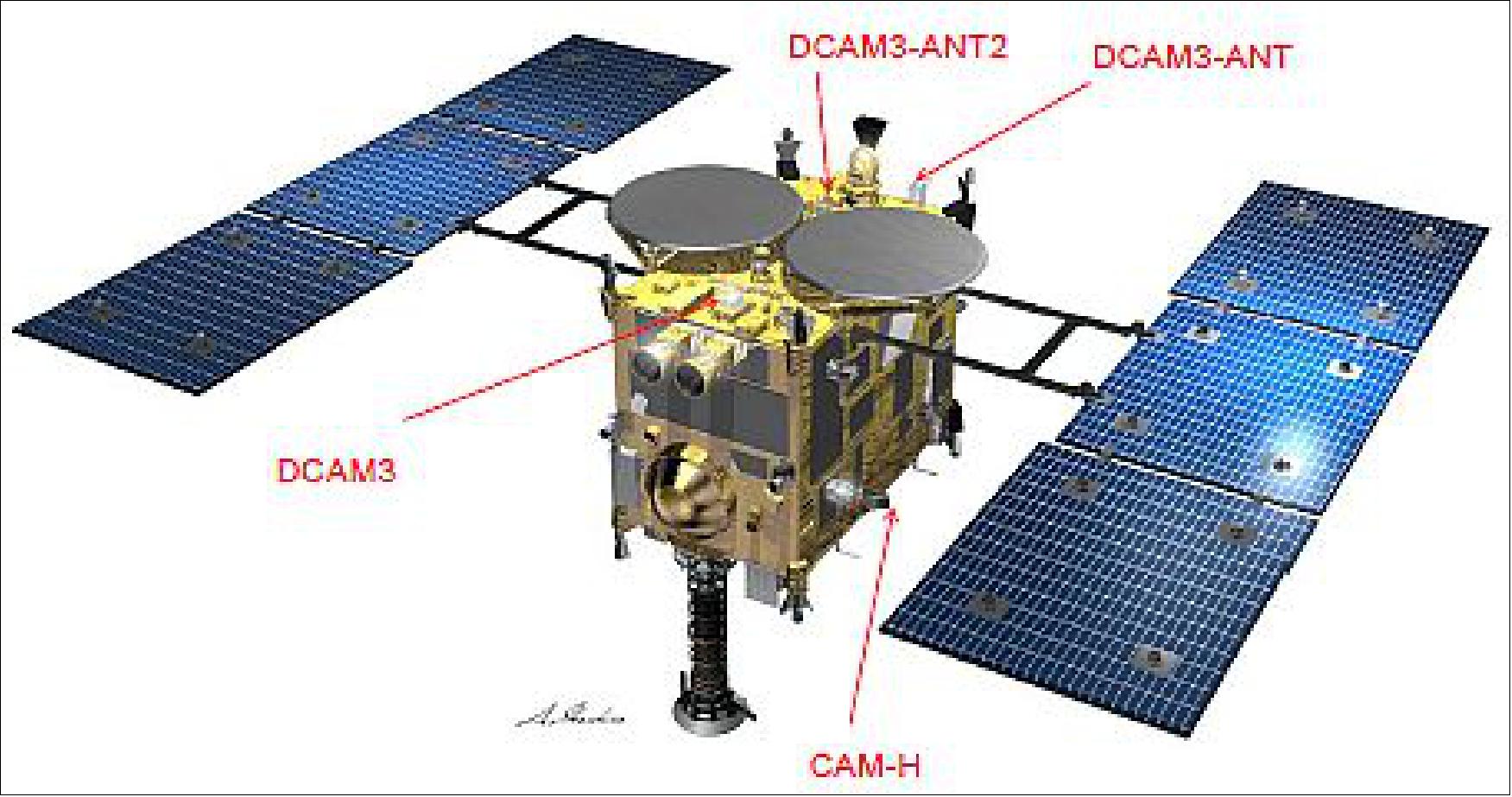

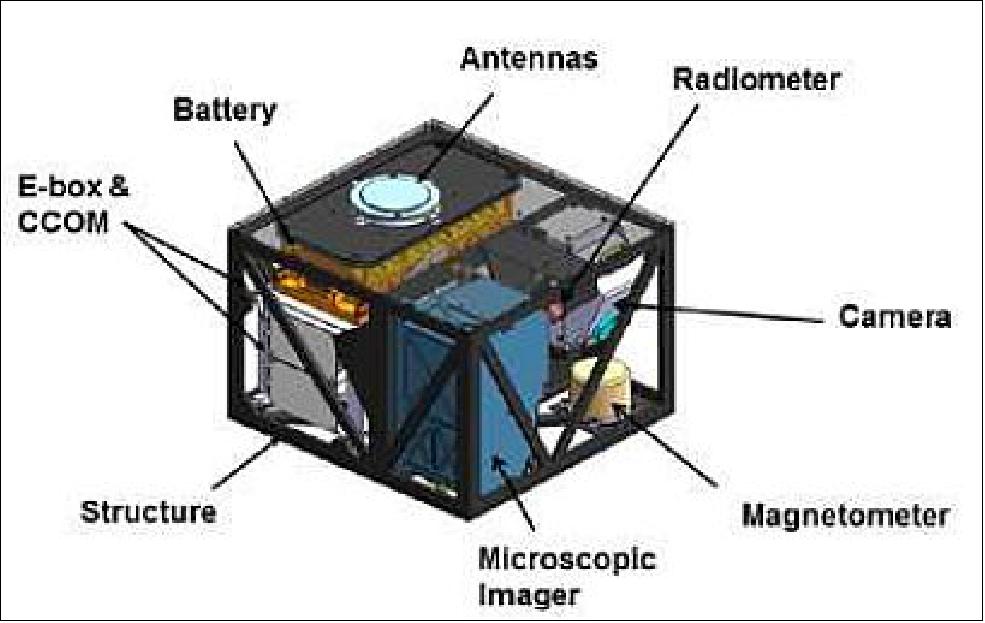

Spacecraft

Japan's Hayabusa-2 spacecraft is designed to study asteroid 1999 JU3 from multiple angles, using remote-sensing instruments, a lander and a rover. It will collect surface- and possibly also subsurface materials from the asteroid and return the samples to Earth in a capsule for analysis. The mission also aims to enhance the reliability of asteroid exploration technologies. 7) 8) 9)

In the current plan, the launch window for Hayabusa-2 is in late 2014. With this schedule, Hayabusa-2 will reach the asteroid in the middle of 2018, and return to the Earth at the end of 2020.

The Hayabusa-2 mission will utilize new technology while further confirming the deep space round-trip exploration technology by inheriting and improving the already verified knowhow established by Hayabusa to construct the basis for future deep-space exploration.

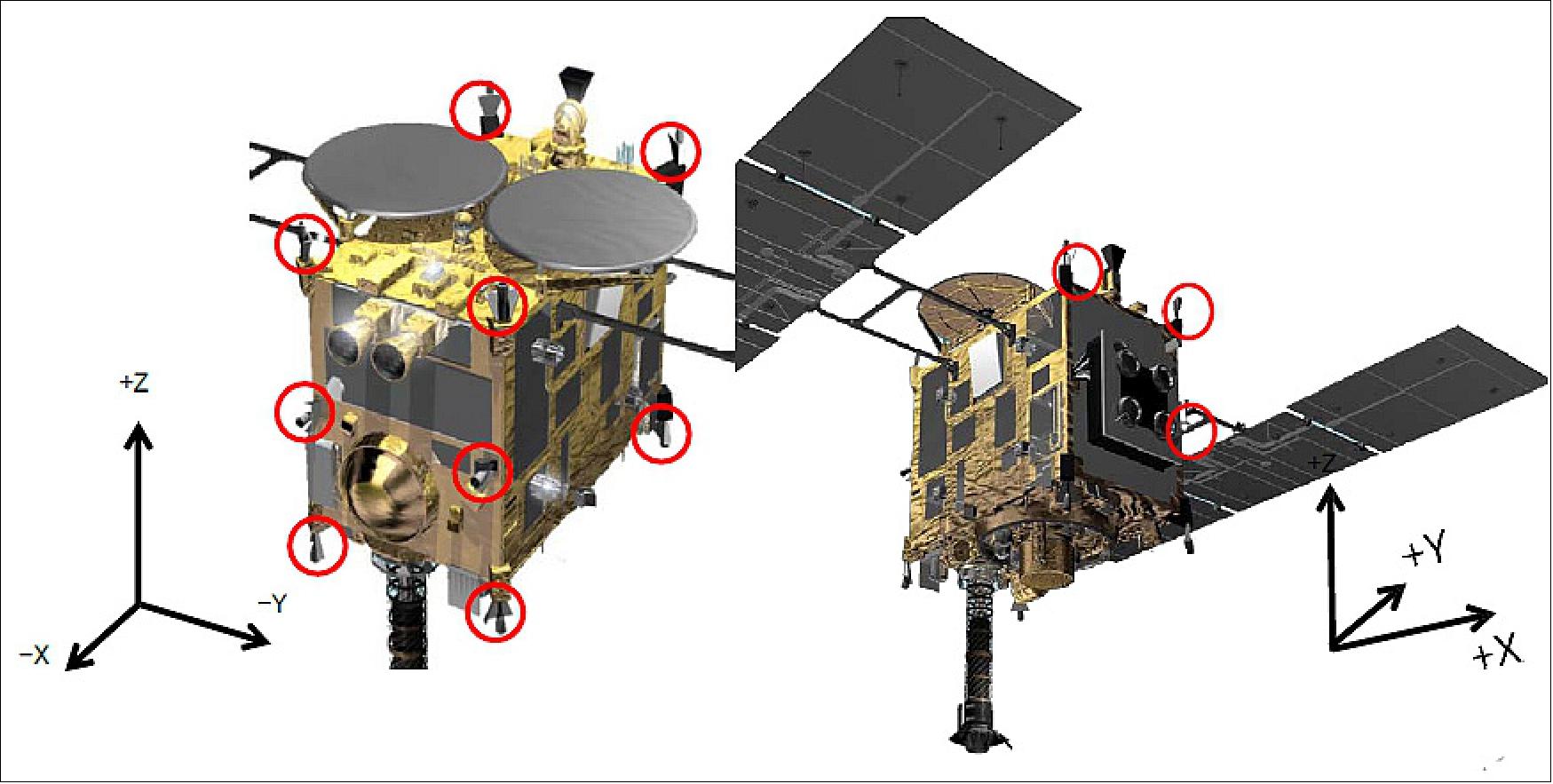

The configuration of Hayabusa-2 is basically the same as that of Hayabusa, with modifications of some parts by introducing novel technologies that evolved after the Hayabusa era. For example:

• The HGA (High Gain Antenna) for Hayabusa featured a parabolic shape, while Hayabusa-2 uses two planar HGAs with a considerably lower mass but with the same performance characteristics. The reason why Hayabusa-2 has two HGAs is that spacecraft has two communication links, Ka-band as well as the X-band links. In daily operations support, the team uses the X-band for data transmission, but for the download of the asteroid observation data, the Ka-band is used to take advantage of the higher data rate of 32 kbit/s, provided by the Ka-band link. The DDOR (Delta-Differential One-way Ranging) technique is used for very accurate plane-of-sky measurements of spacecraft position which complement existing line-of-sight ranging and Doppler measurements.

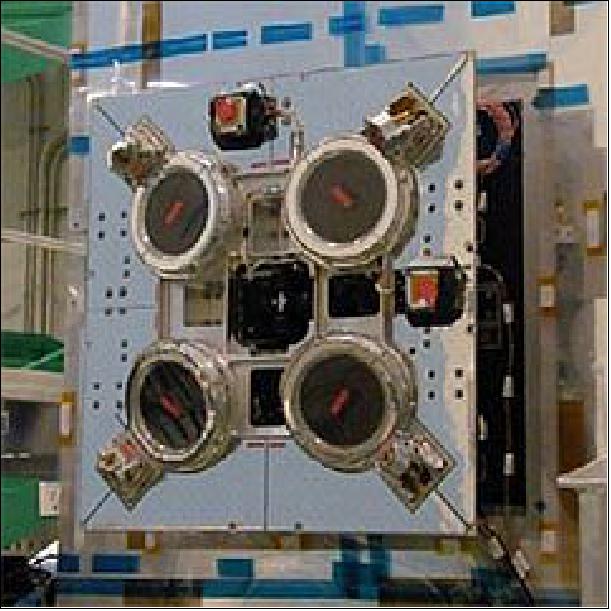

• The AOCS (Attitude and Orbit Control Subsystem) of Hayabusa-2 was improved, now featuring 4 reaction wheels for a more reliable service in case of need.

- During the cruise phase, Hayabusa-2 controls its attitude with only one reaction wheel to bias the momentum around the Z-axis of the body. This is to save the operating life of reaction wheels for other axes, because the project experienced that two reaction wheels of three equipped on Hayabusa were broken after the touchdown mission. 10)

- In this one wheel control mode, the angular momentum direction is slowly moved in the inertial space (generally called precession) due to the solar radiation torque. This attitude motion caused by the balance of the total angular momentum and solar radiation pressure is known to trace the Sun direction automatically with ellipsoidal and spiral motion around Sun direction. Based on this knowledge of the past, the attitude dynamics model for the Hayabusa-2 mission had been developed before the launch. According to the newly developed attitude dynamics model of Hayabusa-2, the precession trajectory is almost the ellipsoid around the attitude equilibrium point, and this equilibrium point is determined mainly by the phase angle around Z-axis of the body.

- In the actual operation of Hayabusa-2, the spacecraft experienced already the one wheel control mode, and the attitude motion in this mode is nearly corresponding to the expected motion based on the dynamics model developed before the launch. The precession trajectory is ellipsoid around the equilibrium point, and the attitude dynamics model is verified by the actual flight data. In this one wheel operation, the Sun aspect angle is restricted within a certain limit angle in terms of the thermal condition of the spacecraft. Because the precession radius is determined by the initial attitude and the equilibrium point, the Sun aspect angle almost exceeds the limit angle due to the precession without change of the equilibrium point. At this operation, the project executes the attitude maneuver around the Z-axis to change the equilibrium point, in order to reduce the Sun aspect angle - and succeeded. After that, the project executed the maneuver again to change the equilibrium point to a close point in order to make the small precession trajectory (Ref. 10).

• IES (Ion Engine System) has been modified to account for the aging effect during extended support periods. The thrust level of IES was increased by 25%, using the same Xe microwave discharge ion engine system.

IES will be used for orbit maneuvers during the cruising of the Hayabusa-2’s onward journey to the asteroid and return trip to Earth. The engine enables to make the round trip with only one tenth of the power consumption compared to that of chemical propellant.

Major improvements from the Hayabusa mission are:

- Countermeasures to plasma ignition malfunction of one ion source of an ion engine. Carefully coordinating each part of the ion engine to improve both ion source propulsion generation efficiency and ignition stability.

- Countermeasures to degradation and malfunction of three neutralizers that occurred after 10,000 to 15,000 hours of operation. To make the neutralizer’s lifespan longer, the walls of the electric discharge chamber are protected from plasma and the magnetic field has been strengthened to decrease the voltage necessary for electron emission.

- The maximum power was successfully increased to 10 mN per ion engine from the conventional 8 mN.

The Hayabusa-2 spacecraft has a stowed size of 1.6 m x 1 m x 1.25 m (height). With the solar panels deployed, the 600 kg satellite as a width of 6 m.

Spacecraft structure | Size: 1.6 m×1.0 m×1.4 m(height) box structure with two fixed SAPs |

Data handling subsystem | - COSMO16 based DHU-PIM bus system |

AOCS (Attitude and Orbit Control Subsystem) | - HR5000S based processor, double redundant |

Propulsion subsystems | - RCS (Reaction Control System): Bi-propellant hydrazine system, 20 N thruster x 12 |

Power subsystem | SAP (Solar Array Paddle): -1.4 kW@1.4 AU, 2.6 kW@1AU; BAT: Li-ion battery 13.2 Ah; power bus: SSR (Series Switching Regulator) system, 50 V bus. |

Communication subsystem | - X-band TT&C (coherent X-up/X-down), data rate: 8 bit/s-32 kbit/s, double redundant. |

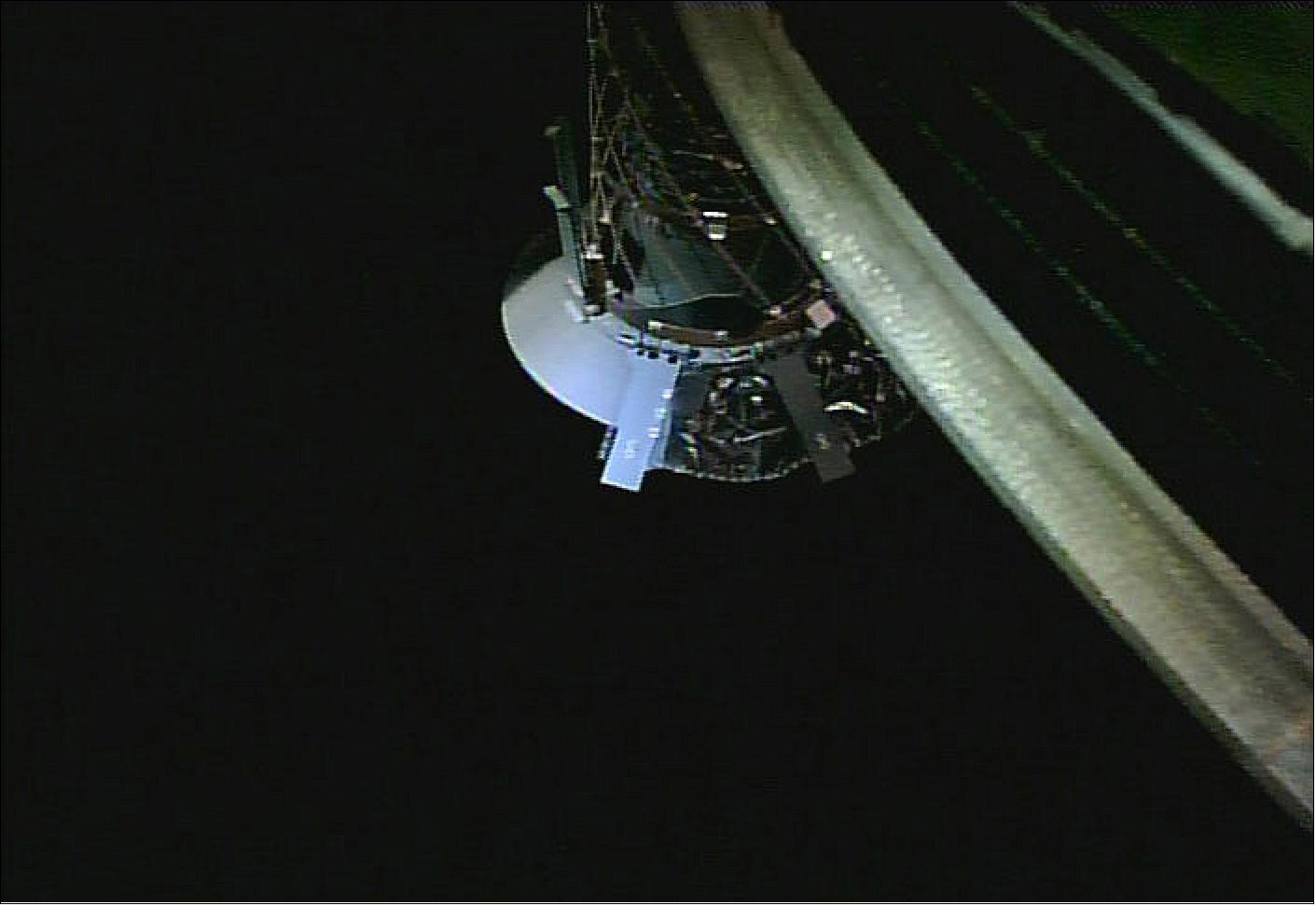

Launch

The Hayabusa-2 spacecraft was launched on December 03, 2014 (04:22:04 UTC) on a H-IIA vehicle (No. 26) from TNSC (Tanegashima Space Center), Japan. The launch service provider was MHI (Mitsubishi Heavy Industries, Ltd). The launch was nominally and about 1 hr 47 minutes and 21 seconds after liftoff, the separation of the Hayabusa-2 spacecraft into an Earth-escape trajectory was confirmed. 11) 12)

Secondary payloads:

• Shin'en-2, a nanosatellite technology demonstration mission (17 kg) of Kyushu Institute of Technology and Kagoshima University, Japan. The objective is to establish communication technologies with a long range as far as moon. Shin'en-2 carries into deep space an F1D digital store-and-forward transponder which offers an opportunity for earthbound radio amateurs to test the limits of their communication capabilities.

• ArtSat-2 (Art Satellite-2)/DESPATCH (Deep Space Amateur Troubadour’s Challenge), a joint project of of Tama Art University and Tokyo University. DESPATCH is a microsatellite of ~30 kg. The microsatellite carries a “deep space sculpture” developed using a 3D printer, as well as an amateur radio payload and a CW beacon at 437.325 MHz.

• PROCYON (PRoximate Object Close flYby with Optical Navigation) is a microsatellite (67 kg) developed by the ISSL (Intelligent Space Systems Laboratory) of the University of Tokyo and JAXA. The objective is to demonstrate microsatellite bus technology for deep space exploration and proximity flyby to asteroids performing optical measurements. 13)

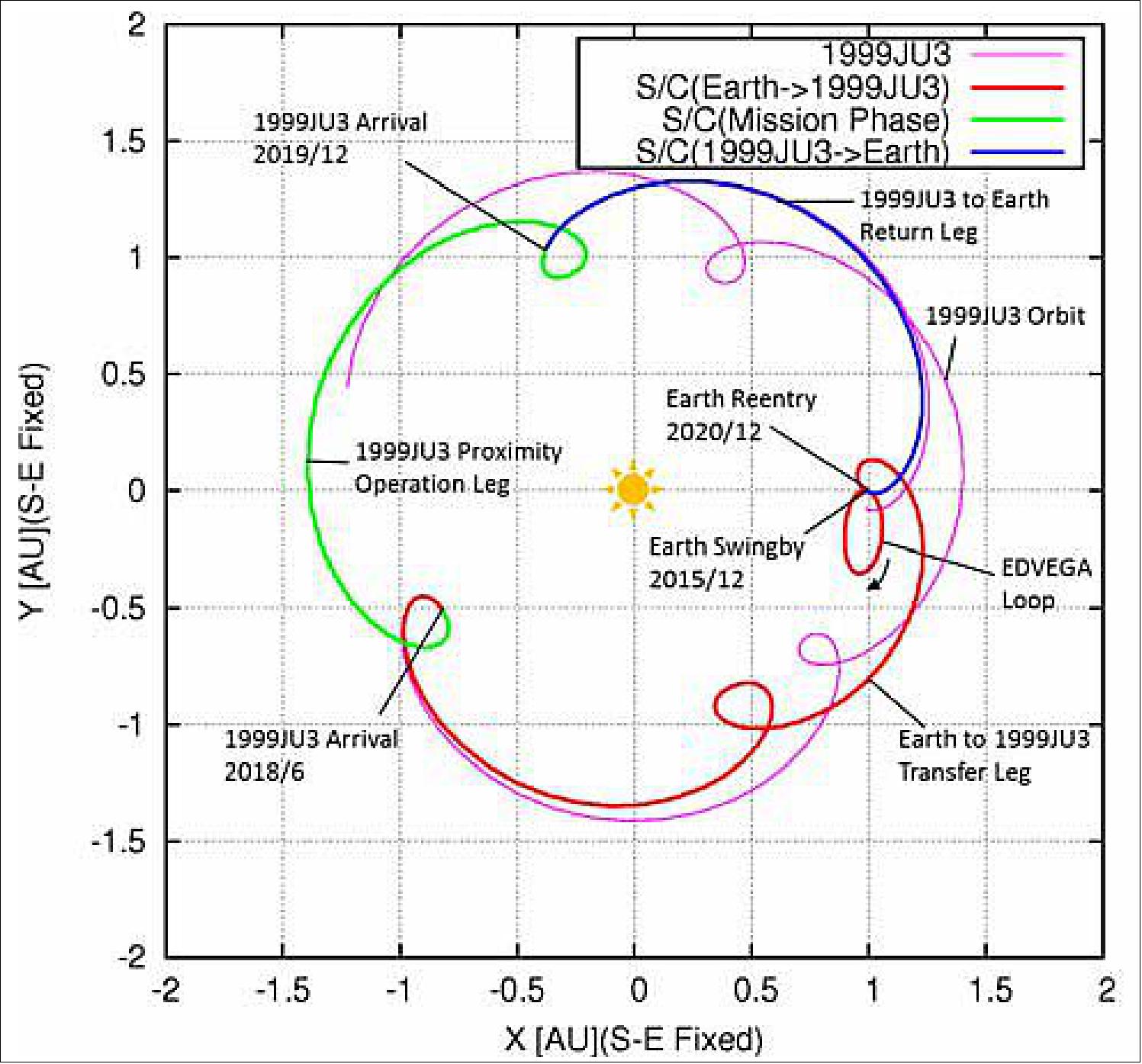

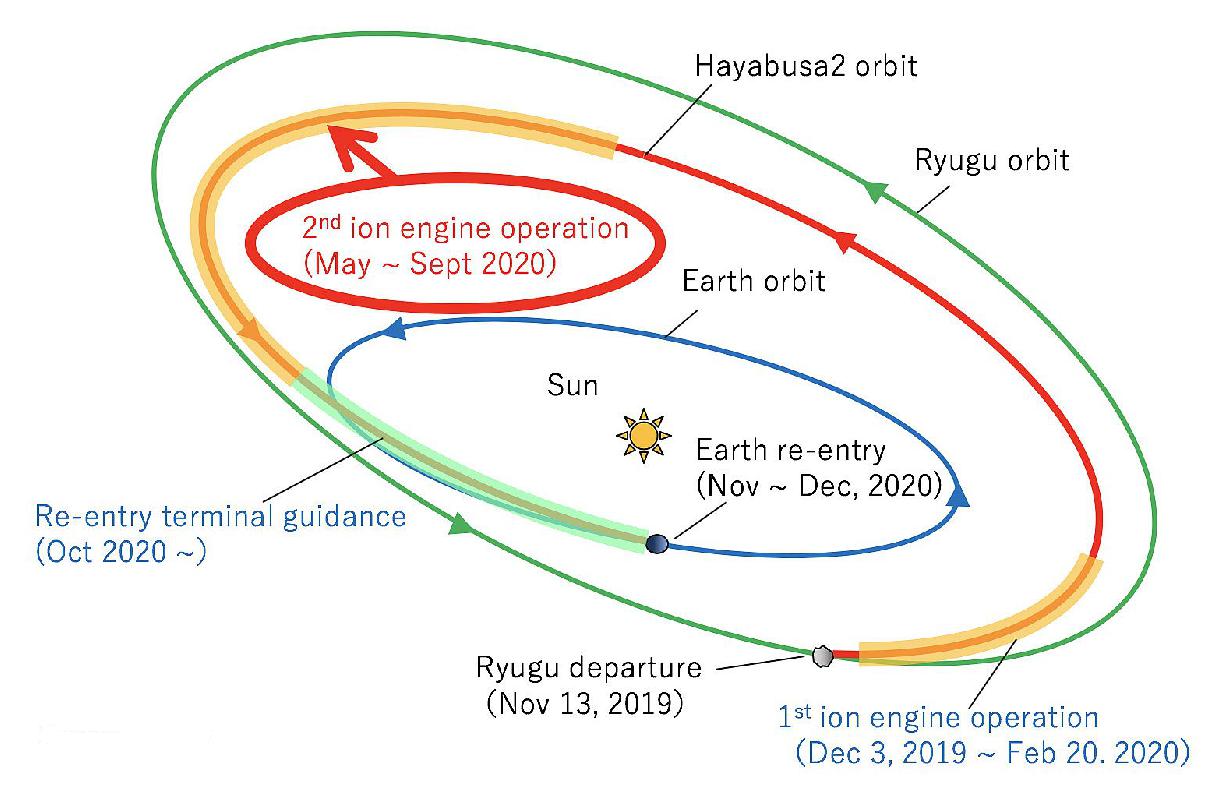

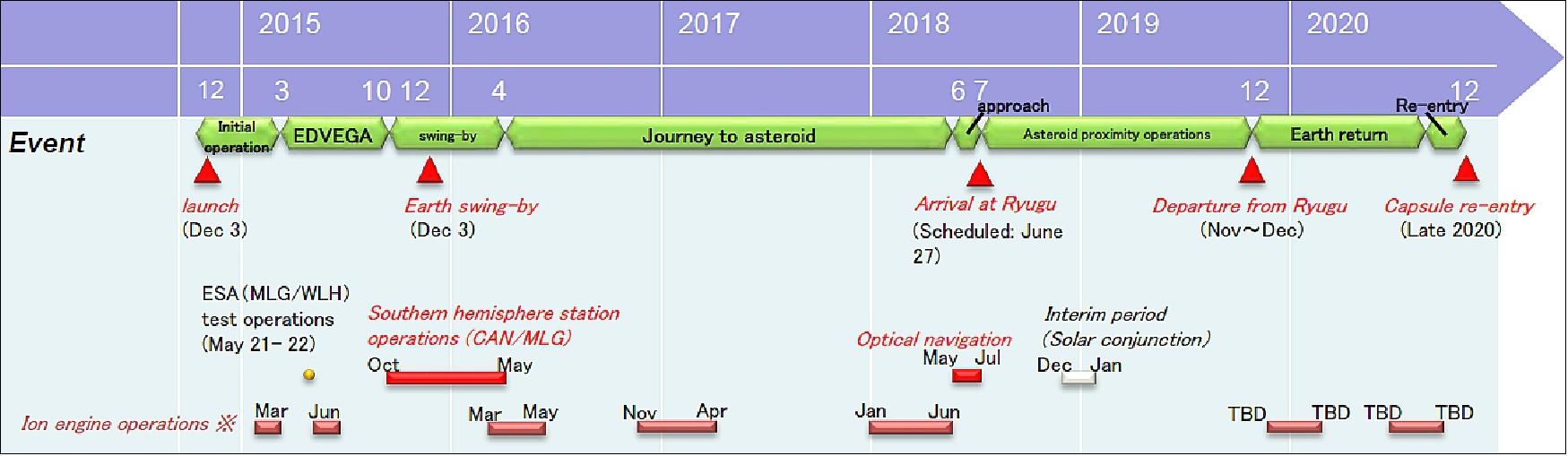

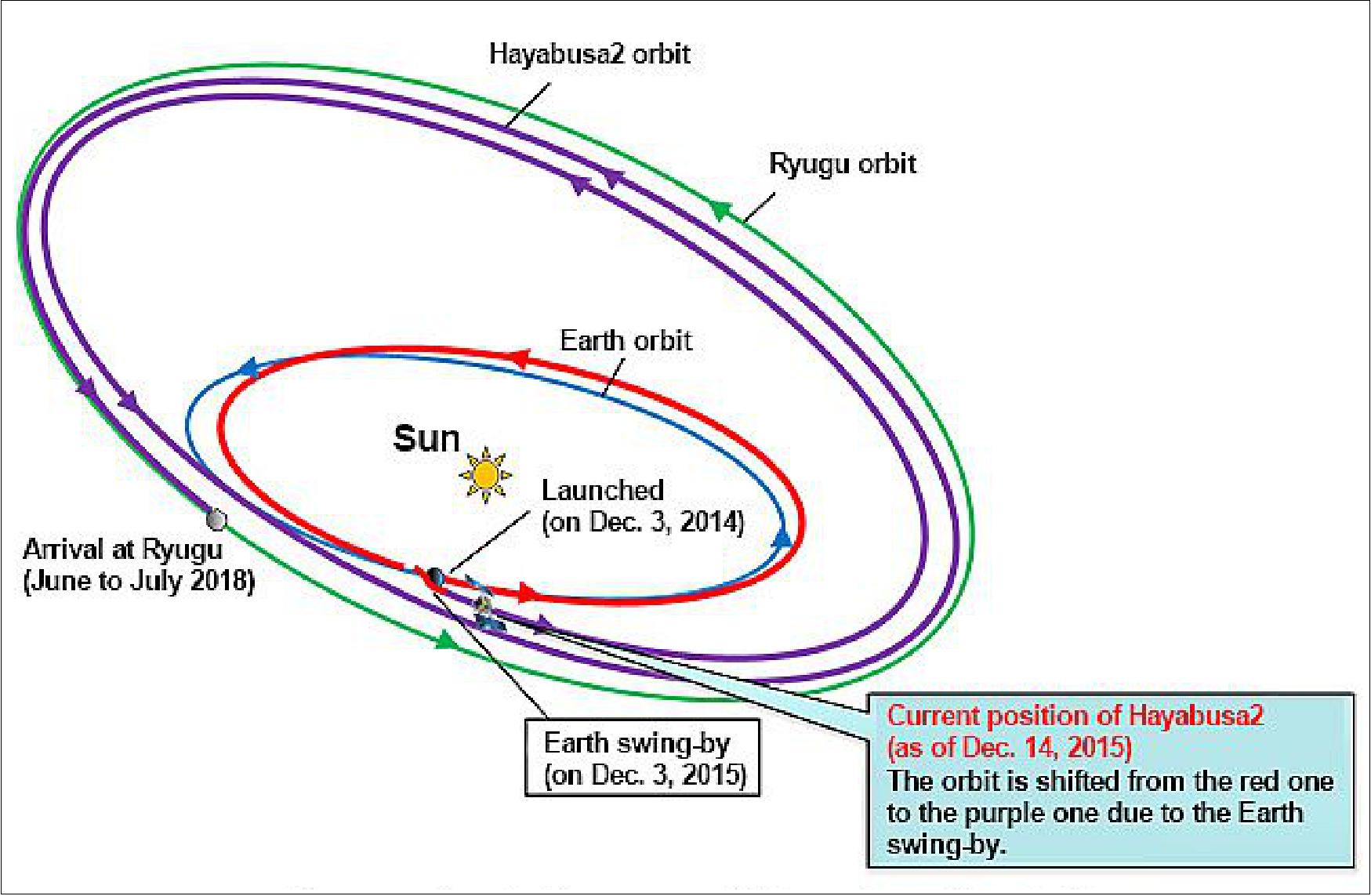

Orbit: The trajectory of Hayabusa-2 for the whole mission is shown in the sun-earth fixed coordinate in Figure 9. The total cruising time is about 4.5 years, and the asteroid proximity period is about 1.5 years. So the total flight time is about 6 years. The departure C3 is 21 km2/s2, the total impulse of the ion engine is 2 km/s, and the reentry speed of the capsule is 11.6 km/s.

Legend to Figure 9: Hayabusa-2 is equipped with a high-specific impulse ion engine system to enable the round-trip mission. First one year after launch is an interplanetary cruise phase called EDVEGA (Electric Delta-V Earth Gravity Assist).

Mission Status

• March 18, 2022: Asteroids hold many clues about the formation and evolution of planets and their satellites. Understanding their history can, therefore, reveal much about our solar system. While observations made from a distance using electromagnetic waves and telescopes are useful, analyzing samples retrieved from asteroids can yield much more detail about their characteristics and how they may have formed. An endeavor in this direction was the Hayabusa mission, which, in 2010, returned to Earth after 7 years with samples from the asteroid Itokawa. 14)

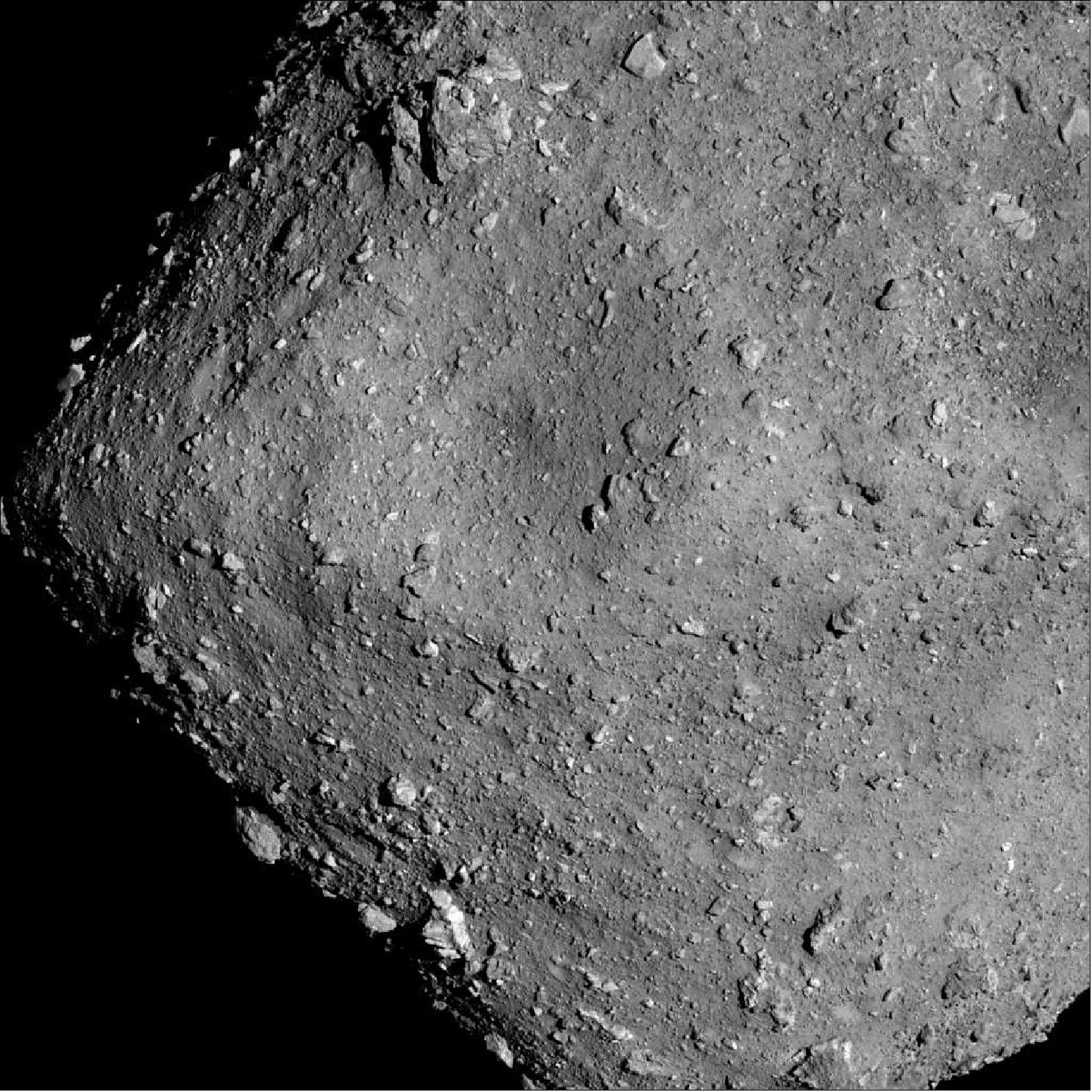

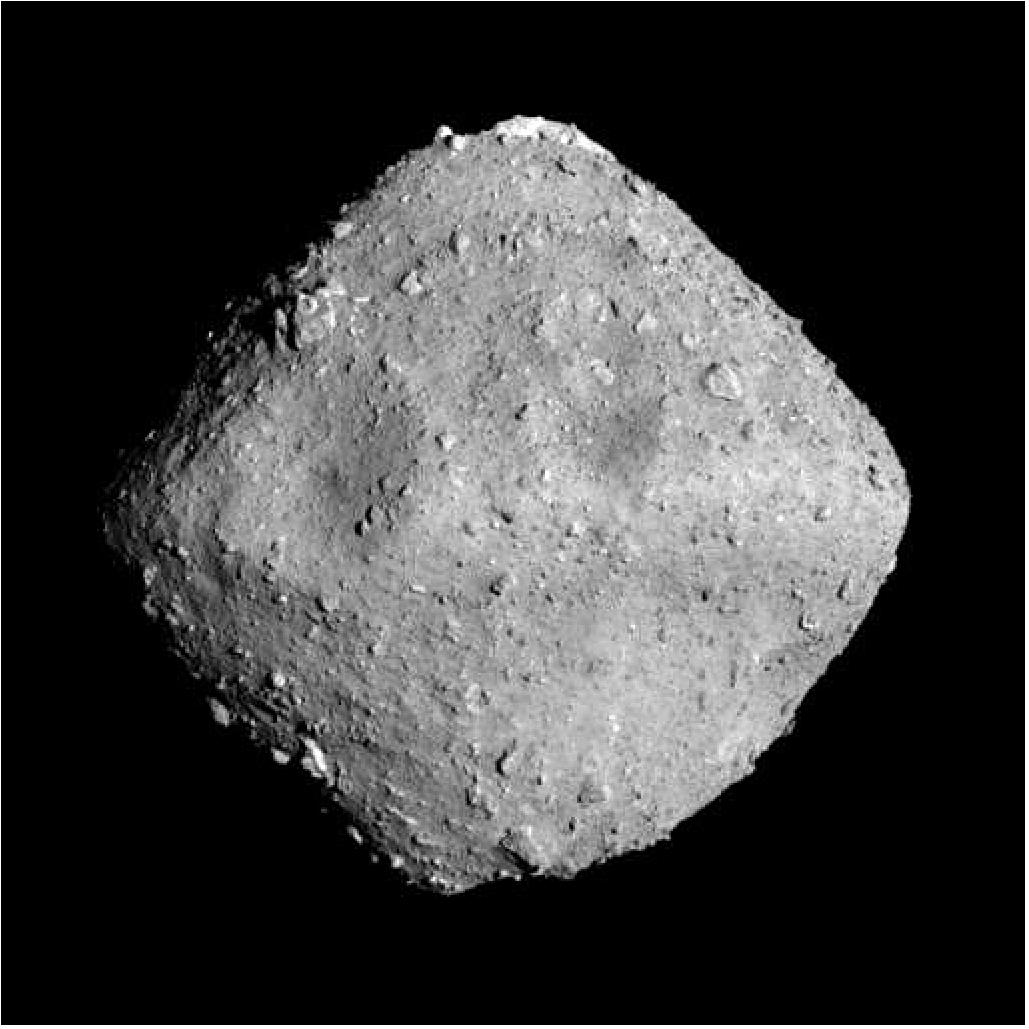

- The successor to this mission, called Hayabusa-2, was completed near the end of 2020, bringing back material from Asteroid 162173 “Ryugu,” along with a collection of images and data gathered remotely from close proximity. While the material samples are still being analyzed, the information obtained remotely has revealed three important features about Ryugu. Firstly, Ryugu is a rubble-pile asteroid composed of small pieces of rock and solid material clumped together by gravity rather than a single, monolithic boulder. Secondly, Ryugu is shaped like a spinning top, likely caused by deformation induced by quick rotation. Third, Ryugu has a remarkably high organic matter content.

- Of these, the third feature raises a question regarding the origin of this asteroid. The current scientific consensus is that Ryugu originated from the debris left by the collision of two larger asteroids. However, this cannot be true if the asteroid is high in organic content (which will confirmed once the analyses of the returned samples are complete). What could, then, be the true origin of Ryugu?

- In a recent effort to answer this question, a research team led by Associate Professor Hitoshi Miura of Nagoya City University, Japan, proposed an alternative explanation backed up by a relatively simple physical model. As explained in their paper published in The Astrophysical Journal Letters, the researchers suggest that Ryugu, as well as similar rubble-pile asteroids, could, in fact, be remnants of extinct comets. This study was carried out in collaboration with Professor Eizo Nakamura and Associate Professor Tak Kunihiro from Okayama University, Japan. 15)

- Comets are small bodies that form on the outer, colder regions of the solar system. They are mainly composed of water ice, with some rocky components (debris) mixed in. If a comet enters the inner solar system— the space delimited by the asteroid belt “before” Jupiter—heat from the solar radiation causes the ice to sublimate and escape, leaving behind rocky debris that compacts due to gravity and forms a rubble-pile asteroid.

- This process fits all the observed features of Ryugu, as Dr. Miura explains, “Ice sublimation causes the nucleus of the comet to lose mass and shrink, which increases its speed of rotation. As a result of this spin-up, the cometary nucleus may acquire the rotational speed required for the formation of a spinning-top shape. Additionally, the icy components of comets are thought to contain organic matter generated in the interstellar medium. These organic materials would be deposited on the rocky debris left behind as the ice sublimates.”

- Overall, this study indicates that spinning top-shaped, rubble-pile objects with high organic content, such as Ryugu and Bennu (the target of the OSIRIS-Rex mission) are comet–asteroid transition objects (CATs). “CATs are small objects that were once active comets but have become extinct and apparently indistinguishable from asteroids,” explains Dr. Miura. “Due to their similarities with both comets and asteroids, CATs could provide new insights into our solar system.”

- Hopefully, detailed compositional analyses of the samples from both Ryugu and Bennu will shed more light on these issues. Make sure to stay tuned!

• January 5, 2021: Last month, Japan’s Hayabusa-2 mission brought home a cache of rocks collected from a near-Earth asteroid called Ryugu. While analysis of those returned samples is just getting underway, researchers are using data from the spacecraft’s other instruments to reveal new details about the asteroid’s past. 16)

- In a study published in Nature Astronomy, 17) researchers offer an explanation for why Ryugu isn’t quite as rich in water-bearing minerals as some other asteroids. The study suggests that the ancient parent body from which Ryugu was formed had likely dried out in some kind of heating event before Ryugu came into being, which left Ryugu itself drier than expected.

- “One of the things we’re trying to understand is the distribution of water in the early solar system, and how that water may have been delivered to Earth,” said Ralph Milliken, a planetary scientist at Brown University and study co-author. “Water-bearing asteroids are thought to have played a role in that, so by studying Ryugu up close and returning samples from it, we can better understand the abundance and history of water-bearing minerals on these kinds of asteroids.”

- One of the reasons Ryugu was chosen as a destination, Milliken says, is that it belongs to a class of asteroids that are dark in color and suspected to have water-bearing minerals and organic compounds. These types of asteroids are believed to be possible parent bodies for dark, water- and carbon-bearing meteorites found on Earth known as carbonaceous chondrites. Those meteorites have been studied in great detail in laboratories around the world for many decades, but it is not possible to determine with certainty which asteroid a given carbonaceous chondrite meteorite may come from.

- The Hayabusa-2 mission represents the first time a sample from one of these intriguing asteroids has been directly collected and returned to Earth. But observations of Ryugu made by Hayabusa-2 as it flew alongside the asteroid suggest it may not to be as water-rich as scientists originally expected. There are several competing ideas for how and when Ryugu may have lost some of its water.

- Ryugu is a rubble pile — a loose conglomeration of rock held together by gravity. Scientists think these asteroids likely form from debris left over when larger and more solid asteroids are broken apart by a large impact event. So it’s possible the water signature seen on Ryugu today is all that remains of a previously more water-rich parent asteroid that dried out due a heating event of some kind. But it could also be that Ryugu dried out after a catastrophic disruption and re-formation as a rubble pile. It’s also possible that Ryugu had a few close spins past the sun in its past, which could have heated it up and dried out its surface.

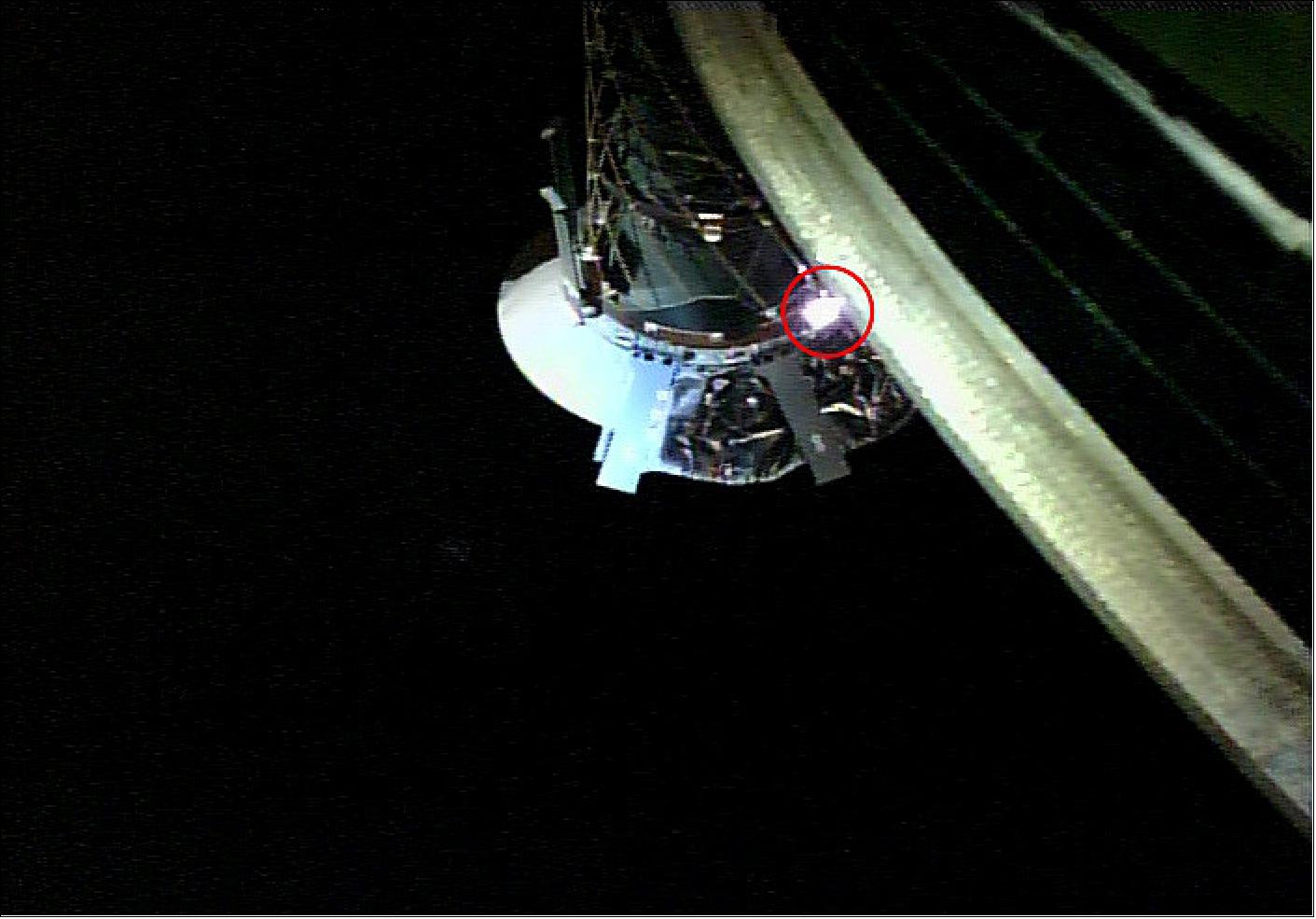

- The Hayabusa-2 spacecraft had equipment aboard that could help scientists to determine which scenario was more likely. During its rendezvous with Ryugu in 2019, Hayabusa-2 fired a small projectile into the asteroid’s surface. The impact created a small crater and exposed rock buried in the subsurface. Using a near-infrared spectrometer, which is capable of detecting water-bearing minerals, the researchers could then compare the water content of surface rock with that of the subsurface.

- The data showed the subsurface water signature to be quite similar to that of the outermost surface. That finding is consistent with the idea that Ryugu’s parent body had dried out, rather than the scenario in which Ryugu’s surface was dried out by the sun.

- “You’d expect high-temperature heating from the sun to happen mostly at the surface and not penetrate too far into the subsurface,” Milliken said. “But what we see is that the surface and subsurface are pretty similar and both are relatively poor in water, which brings us back to the idea that it was Ryugu’s parent body that had been altered.”

- More work needs to be done, however, to confirm the finding, the researchers say. For example, the size of the particles excavated from the subsurface could influence the interpretation of the spectrometer measurements.

- “The excavated material may have had a smaller grain size than what’s on the surface,” said Takahiro Hiroi, a senior research associate at Brown and study co-author. “That grain size effect could make it appear darker and redder than its coarser counterpart on the surface. It’s hard to rule out that grain-size effect with remote sensing.”

- Luckily, the mission isn’t limited to studying samples remotely. Since Hayabusa2 successfully returned samples to Earth in December, scientists are about to get a much closer look at Ryugu. Some of those samples may soon be coming to the NASA Reflectance Experiment Laboratory (RELAB) at Brown, which is operated by Hiroi and Milliken.

- Milliken and Hiroi say they’re looking forward to seeing if the laboratory analyses corroborate the team’s remote sensing results.

- “It’s the double-edged sword of sample return,” Milliken said. “All of those hypotheses we make using remote sensing data will be tested in the lab. It’s super-exciting, but perhaps also a little nerve-wracking. One thing is for certain, we’re sure to learn a lot more about the links between meteorites and their parent asteroids.”

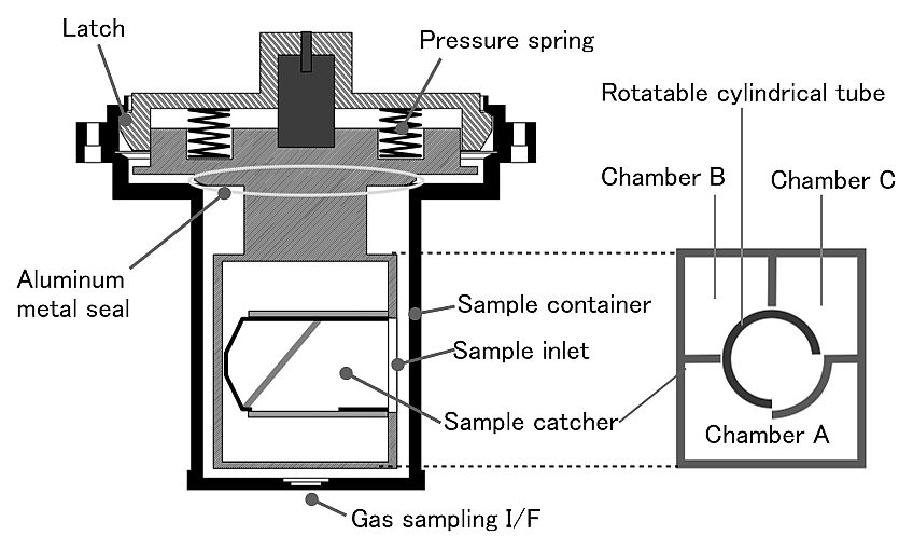

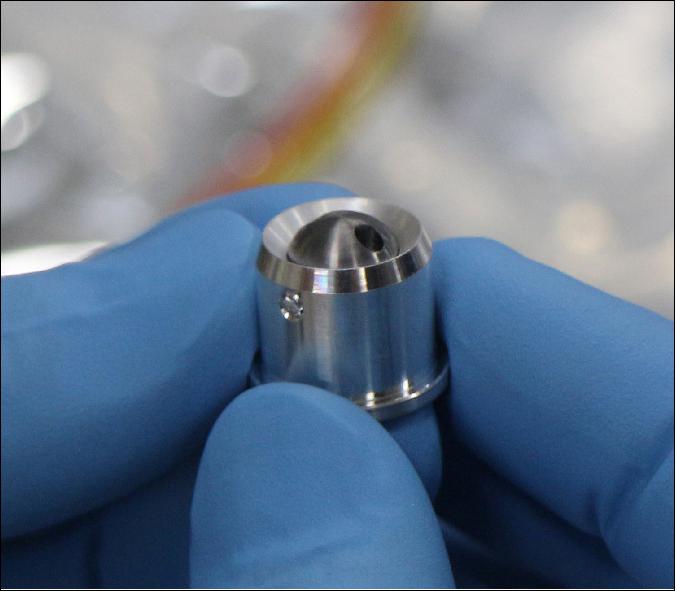

• December 15, 2020: JAXA has confirmed that the gas collected from the sample container inside the reentry capsule of the asteroid explorer, Hayabusa-2, is a gas sample originating from asteroid Ryugu. 18)

- The result of the mass spectrometry of the collected gas within the sample container performed at the QLF (Quick Look Facility) established at the Woomera Local Headquarters in Australia on December 7, 2020, suggested that the gas differed from the atmospheric composition of the Earth. For additional confirmation, a similar analysis was performed on December 10 – 11 at the Extraterrestrial Sample Curation Center on the JAXA Sagamihara Campus. This has led to the conclusion that the gas in the sample container is derived from asteroid Ryugu.

The grounds for making this decision are due to the following three points:

a) Gas analysis at the Extraterrestrial Sample Curation Center and at the Woomera Local Headquarters in Australia gave the same result.

b) The sample container is sealed with an aluminum metal seal and the condition of the container is as designed, such that the inclusion of the Earth’s atmosphere was kept well below the permissible level during the mission.

c) Since it was confirmed on the Sagamihara campus that gas of the same composition had been generated even after the removal of the container gas in Australia, it is considered that the collected gas must be due to the degassing from the sample.

- This is the world’s first sample return of a material in the gas state from deep space.

- The initial analysis team will continue with opening the sample container and performing a detailed analysis of the molecular and isotopic composition of the collected gas.

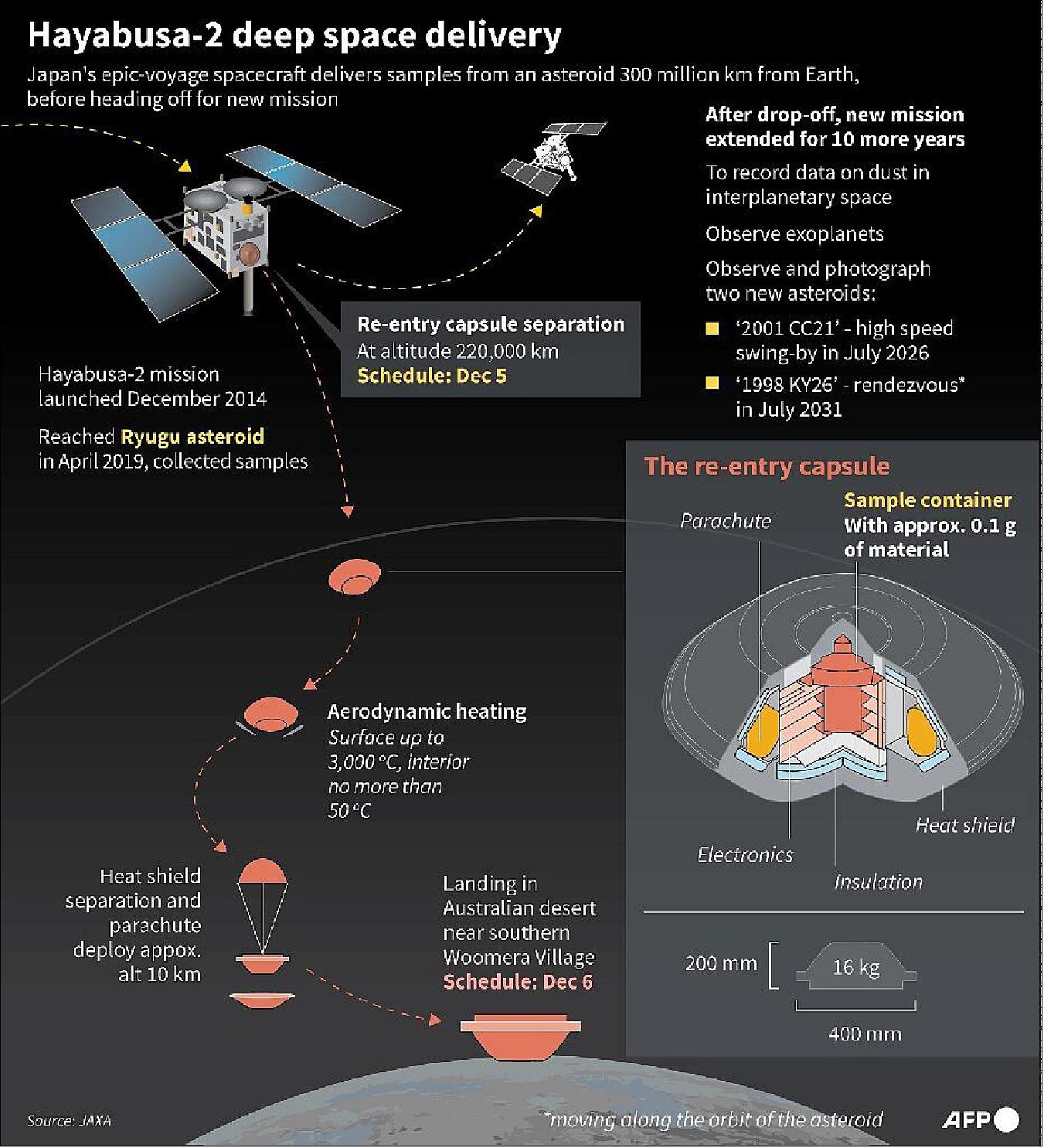

• On December 6, 2020 local time (Dec. 5 in the United States), the Japanese spacecraft Hayabusa-2 dropped a capsule to the ground of the Australian Outback from about 120 miles (or 200 km) above Earth’s surface. Inside that capsule is some of the most precious cargo in the solar system: dust that the spacecraft collected earlier this year from the surface of asteroid Ryugu. 19)

- By the close of 2021, JAXA (Japan Aerospace Exploration Agency) will disperse samples of Ryugu to six teams of scientists around the globe. These researchers will prod, heat, and inspect these ancient grains to learn more about their origins.

- Among the teams of Ryugu investigators will be scientists from the Astrobiology Analytical Laboratory at NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center in Greenbelt, Maryland. Researchers in the astrobiology lab use cutting-edge instruments that are similar to those used in forensic labs to solve crimes. Instead of solving crimes, though, NASA Goddard scientists probe space rocks for molecular evidence that can help them piece together the history of the early solar system.

- “What we’re trying to do is better understand how Earth evolved into what it is today,” said Jason P. Dworkin, director of the Goddard’s Astrobiology Analytical Laboratory. “How, from a disk of gas and dust that coalesced around our forming Sun, did we get to life on Earth and possibly elsewhere?” Dworkin serves as the international deputy of a global team that will probe a sample of Ryugu in search of organic compounds that are precursors to life on Earth.

- Ryugu is an ancient fragment of a larger asteroid that formed in the cloud of gas and dust that spawned our solar system. It is an intriguing type of asteroid that’s rich in carbon, which is an element essential to life.

- When Dworkin and his team receive their share of a Ryugu sample next summer, they will look for organic compounds, or carbon-based compounds, in order to better understand how these compounds first formed and spread throughout the solar system.

- Organic compounds of interest to astrobiologists include amino acids, which are molecules that make up the hundreds of thousands of proteins responsible for powering some of life’s most essential functions, such as making new DNA. By studying the differences in the types and amounts of amino acids preserved in space rocks scientists can build a record of how these molecules formed.

- Dust from Ryugu, which is currently 9 million miles, or 15 million km, from Earth, will be among the most immaculately preserved space material scientists have laid hands on. It’s only the second sample of an asteroid that has ever been collected in space and returned to Earth.

- Before the Ryugu delivery, JAXA brought back tiny samples of asteroid Itokawa in 2010 as part of the first asteroid sampling mission in history. Prior to that, in 2006, NASA obtained a small sample from comet Wild-2 as part of its Stardust mission. And next, in 2023, NASA’s OSIRIS-REx will return at least a dozen ounces, or hundreds of grams, of the asteroid Bennu, which has been traveling through space and largely unaltered for billions of years.

- “Our final objective is to understand how organic compounds formed in the extraterrestrial environment,” said Hiroshi Naraoka, professor of geochemistry at Kyushu University in Fukuoka, Japan, and the lead of the global Hayabusa-2 team that will analyze Ryugu’s organic composition. “So we want to analyze many organic compounds, including amino acids, sulfur compounds, and nitrogen compounds, to build a story of the types of organic synthesis that happens in asteroids.”

- After analyzing the makeup of Ryugu, scientists will get to compare it to Bennu, the site of a wildly successful sample grab by OSIRIS-REx, which briefly touched down on the asteroid’s surface on Oct. 20.

- “The two asteroids have similar shapes, but Bennu appears to have a lot more evidence of past water and of organic compounds,” said Dworkin, whose lab also is due to receive a tenth of an ounce, or several grams, of Bennu. “It’ll be very interesting to see how they compare, given they came from different parent bodies in the asteroid belt and have different histories.”

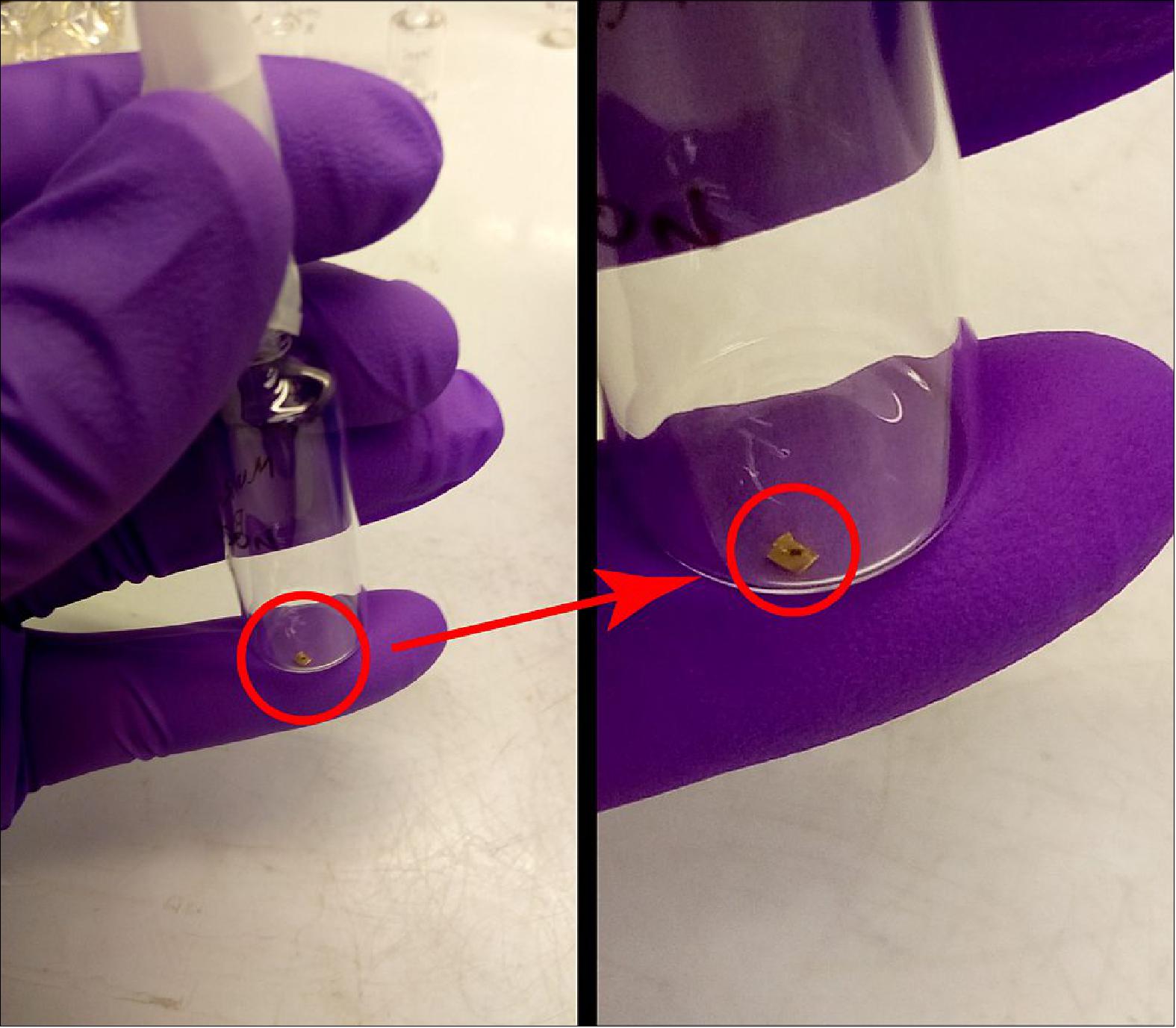

Analyzing Asteroid Particles

- Analyzing Ryugu dust will be one of the most demanding projects Goddard astrochemists have tackled. They will have to work with a miniscule amount of sample. Hayabusa-2 is expected to have collected no more than a few grams of dust (that’s about six coffee beans!) from Ryugu, although this is much more material than was returned from Itokawa. This tiny amount will be dispersed among many scientists, which means Dworkin and his colleagues will get only a fraction of the original sample — slightly more than a typical snowflake.

- “We’ll be dealing with much smaller sample allotments than we typically work with when we analyze meteorites,” said Eric T. Parker, a Goddard astrochemist who works with Dworkin.

- Parker said that the Goddard team, in collaboration with international colleagues, has been practicing working with tiny samples for more than a year. For example, they’ve analyzed dust grains from a carbon-rich meteorite called Murchison. Then, they used the identical technique to analyze a sample without any extraterrestrial material in it to make sure they could tell the difference between the two.

- After Goddard scientists receive Ryugu dust, they will suspend the particles in a water solution inside a glass tube. They will then heat the solution to the temperature of boiling water, or 212º Fahrenheit (100 º Celsius), for 24 hours in an attempt to extract any organic compounds that can dissolve in water.

- The researchers will run the solution through powerful analytical machines that will separate the molecules inside by shape and mass and identify each kind.

- “With really precious samples like Ryugu, of course you think, ‘I hope this test tube doesn’t break,’ or ‘I hope this reaction goes correctly,’” said Hannah L. McLain, a Goddard researcher on Dworkin’s Ryugu analysis team. “But at this point, we’ve fully established our technique to be sure nothing can go wrong and we are excited to analyze the real sample.”

• December 8, 2020: JAXA statement: ”We are pleased to announce that the Hayabusa-2 reentry capsule that was recovered in Woomera, Australia, arrived at the Extraterrestrial Sample Curation Center established on the JAXA Sagamihara Campus, at 11:27 (JST) on December 8, 2020.” 20)

• December 7, 2020: Officials of JAXA (Japan Aerospace Exploration Agency) hailed the arrival of rare asteroid samples on Earth after they were collected by the space probe Hayabusa-2 during an unprecedented mission. 21)

- In a streak of light across the night sky, a capsule containing the precious specimens taken from a distant asteroid arrived on Earth after being dropped off by the probe.

- "After six years of space travel, the box of treasures was able to land in Australia's Woomera this morning," Databus-2 project manager Yuichi Tsuda told a press conference.

- The capsule carrying samples entered the atmosphere just before 2:30 am Japan time (17:30 GMT Saturday, 5 December), creating a shooting-star-like fireball as it entered Earth's atmosphere en route to the landing site Down Under.

- A few hours later, JAXA confirmed the samples had been recovered, with help from beacons emitted by the capsule as it plummeted to Earth after separating from Hayabusa-2 on Saturday, while the fridge-sized probe was about 220,000 km away.

- The capsule, recovered in the southern Australian desert, will now be in the hands of scientists performing initial analysis including checking for any gas emissions. — It will then be sent to Japan.

- Megan Clark, chief of the Australian Space Agency, congratulated the "wonderful achievement — 2020 has been a difficult year all around the world" but the Hayabusa-2 helped "renew our faith in the world, and our trust (in) and appreciation" of the science of the outer universe, she said.

Samples with Organic Material?

- The samples were collected by Hayabusa-2, which launched in 2014, from the asteroid Ryugu, about 300 million kilometers from Earth.

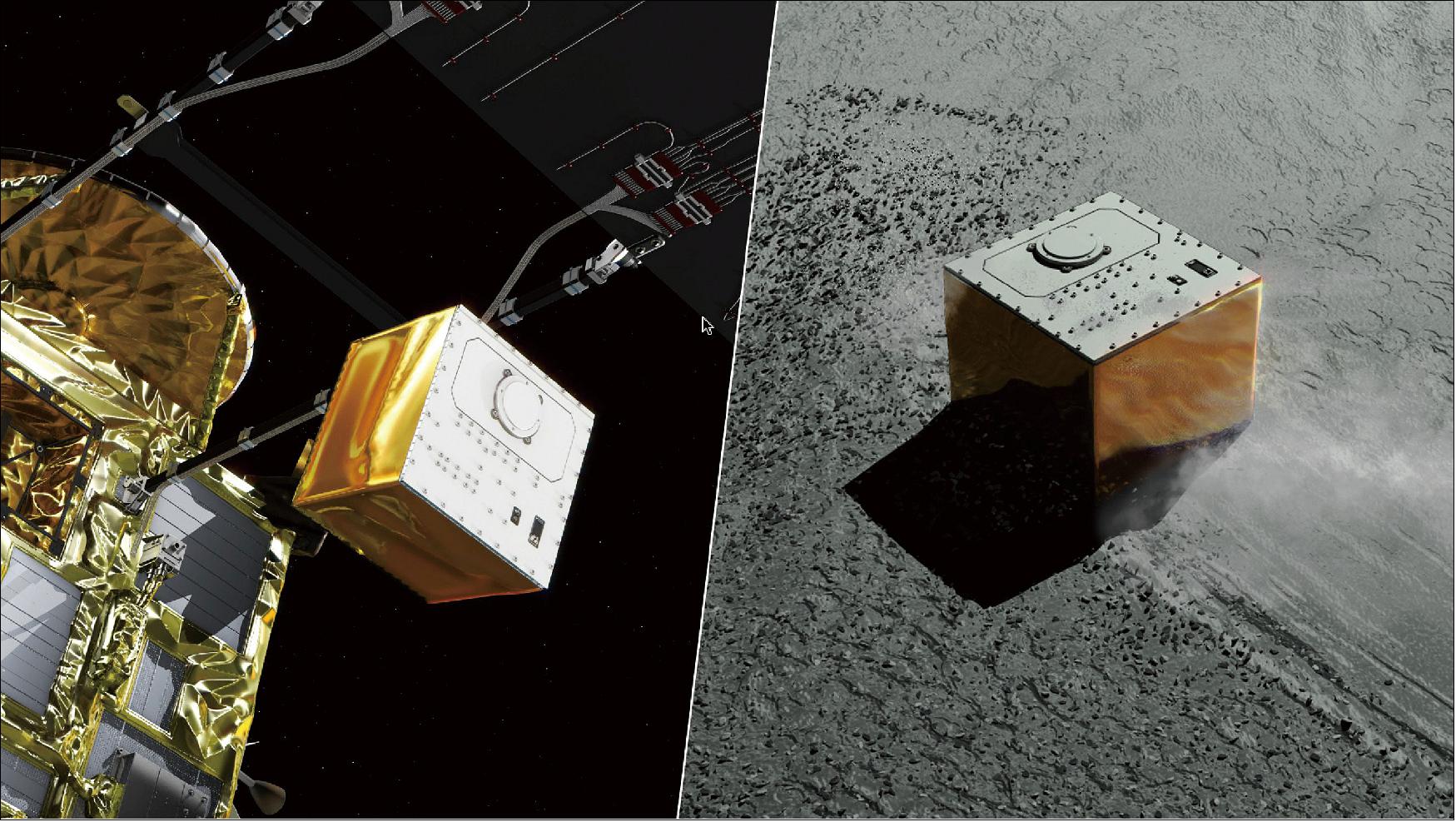

- The probe collected both surface dust and pristine material from below the surface that was stirred up by firing an "impactor" into the asteroid.

- The material is believed to be unchanged since the time the universe was formed.

- Larger celestial bodies like Earth went through radical changes including heating and solidifying, changing the composition of the materials on their surface and below.

- But "when it comes to smaller planets or smaller asteroids, these substances were not melted, and therefore it is believed that substances from 4.6 billion years ago are still there," Hayabusa-2 mission manager Makoto Yoshikawa told reporters before the capsule arrived.

- Scientists are especially keen to discover whether the samples contain organic matter, which could have helped seed life on Earth.

- "We still don't know the origin of life on Earth and through this Hayabusa-2 mission, if we are able to study and understand these organic materials from Ryugu, it could be that these organic materials were the source of life on Earth," Yoshikawa said.

- "We've never had materials like this before... water and organic matters will be subject to research, so this is a very valuable opportunity," said Motoo Ito, senior researcher at the Japan Agency for Marine-Earth Science and Technology.

- Half of Hayabusa-2's samples will be shared between JAXA, US space agency NASA and other international organizations, and the rest kept for future study as advances are made in analytic technology.

More Tasks

- The work is not over for Hayabusa-2, which will now begin an extended mission targeting two new asteroids.

- With half of the xenon fuel for its ion engine remaining, the Hayabusa-2 spacecraft is now headed back out into deep space to embark on an extended mission, using the visit to Earth to alter its orbit.

- It will complete a series of orbits around the sun for around six years before approaching the first of the asteroids—named 2001 CC21—in July 2026.

- Hayabusa-2 will then head towards its main target, 1998 KY26, a ball-shaped asteroid with a diameter of just 30 meters.

- When the probe arrives at the asteroid in July 2031, it will be approximately 300 million km from Earth.

- It will observe and photograph the asteroid, no easy task given that it is spinning rapidly, rotating on its axis about every 10 minutes.

- But Hayabusa-2 is unlikely to land and collect samples, as it probably would not have enough fuel to return them to Earth.

• On December 6, 2020, JAXA has recovered the body of the capsule, the heat shields, and the parachute of the "Hayabusa-2" reentry capsule in the Woomera Prohibited Area (WPA), Australia. 22)

- Tomorrow, the capsule recovery team will extract gas out of the capsule at the operation headquarters in Australia. Researchers considered the gas originates from the precious sample from Asteroid Ryugu.

- After the capsule separation, the spacecraft performed trajectory correction maneuvers three times every 30 minutes to depart from the Earth's sphere from 15:30 to 16:30 on December 5 (JST). The Hayabusa-2 team members confirmed the trajectory correction maneuvers' success at 16:31 on the same day (JST). The current status of the spacecraft is normal.

- We take this opportunity to show our deepest gratitude to the governments of Australia and Japan, NASA, and relevant parties for their cooperation in the recovery of the "Hayabusa-2" reentry capsule. Our appreciation extends to the people of Japan and the world for their generous support and encouragement.

• December 6, 2020: The team behind ESA’s Hera asteroid mission for planetary defence congratulates JAXA for returning Hayabusa-2’s capsule to Earth laden with pristine asteroid samples. They look forward to applying insights from this audacious space adventure to their own mission. 23)

- After 3.2 billion km of travel through space, Hayabusa-2’s reentry capsule parachuted down to Australia’s remote desert Woomera Prohibited Area on Saturday 5 December.

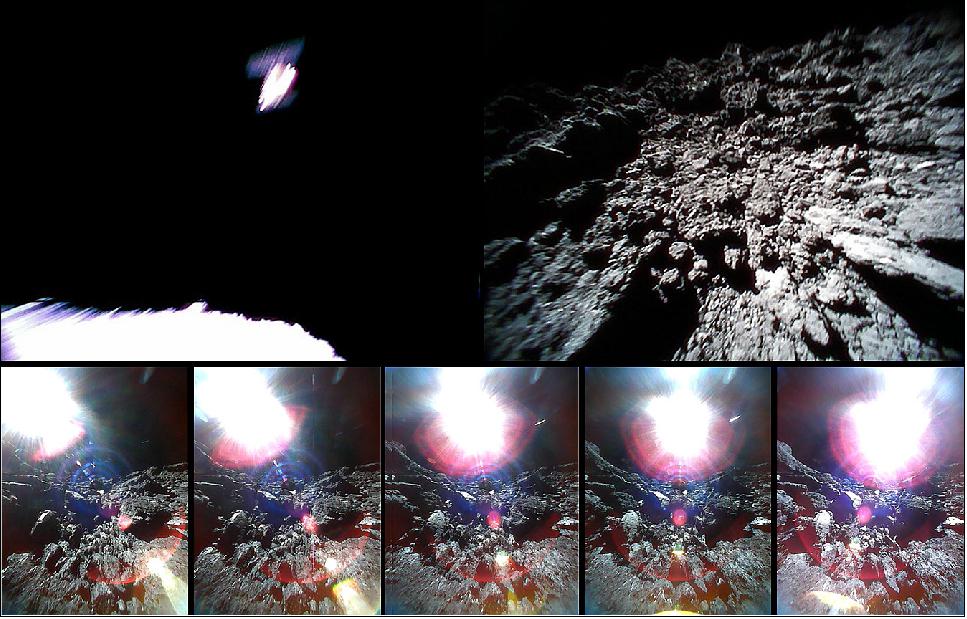

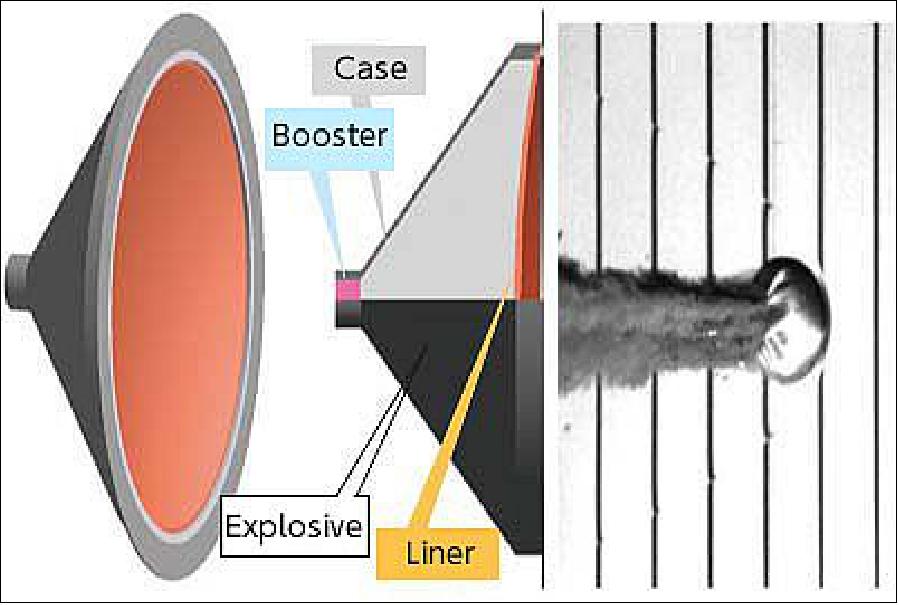

- Within the capsule is material gathered from the Ryugu near-Earth asteroid during two sampling operations: an initial touchdown sampling in February 2019 was followed by a second one in July that year that collected subsurface samples after blasting the face of the asteroid with an explosive impactor.

- Patrick Michel, CNRS Director of Research of France’s Côte d'Azur Observatory, serves as co-investigator and interdisciplinary scientist on the Japanese mission and as Principal Investigator on ESA’s Hera. He comments: “Hayabusa-2’s samples should give us an extraordinary opportunity to measure with high accuracy the composition and other material properties of its carbonaceous asteroid target.

- The 900-m diameter Ryugu has a spinning top shape; its density is very low and based on the results of the Small Carry-on Impactor (SCI) impact experiment performed in April 2019, its surface appears cohesionless. These findings are extremely relevant to planetary defense, which is the prime goal of the Hera mission.”

- Hera will not return any samples to Earth, but will be following Hayabusa2’s approach in one notable respect.

- When it arrives at its target Didymos asteroid system in late 2026 ESA’s desk-sized spacecraft will similarly examine subsurface material, this time excavated by a far more powerful explosive impact: NASA’s DART spacecraft will in the meantime have collided with the smaller of the two Didymos asteroids in 2022, which will attempt to shift the orbit of the asteroid in a measurable way.

- To give an idea, Hayabusa2’s SCI 2.5-kg copper projectile shot into the surface of the 900-m diameter Ryugu asteroid at a velocity of around 2 km per second. NASA’s DART will have a mass of 550 kg, and will strike Didymoon at 6 km/s.

- Patrick Michel adds: “Hayabusa-2’s impact represents a crucial first data point, in anticipation of DART’s impact, striking an asteroid five times smaller with an object more than 200 times larger while moving three times as fast, to move its orbit.”

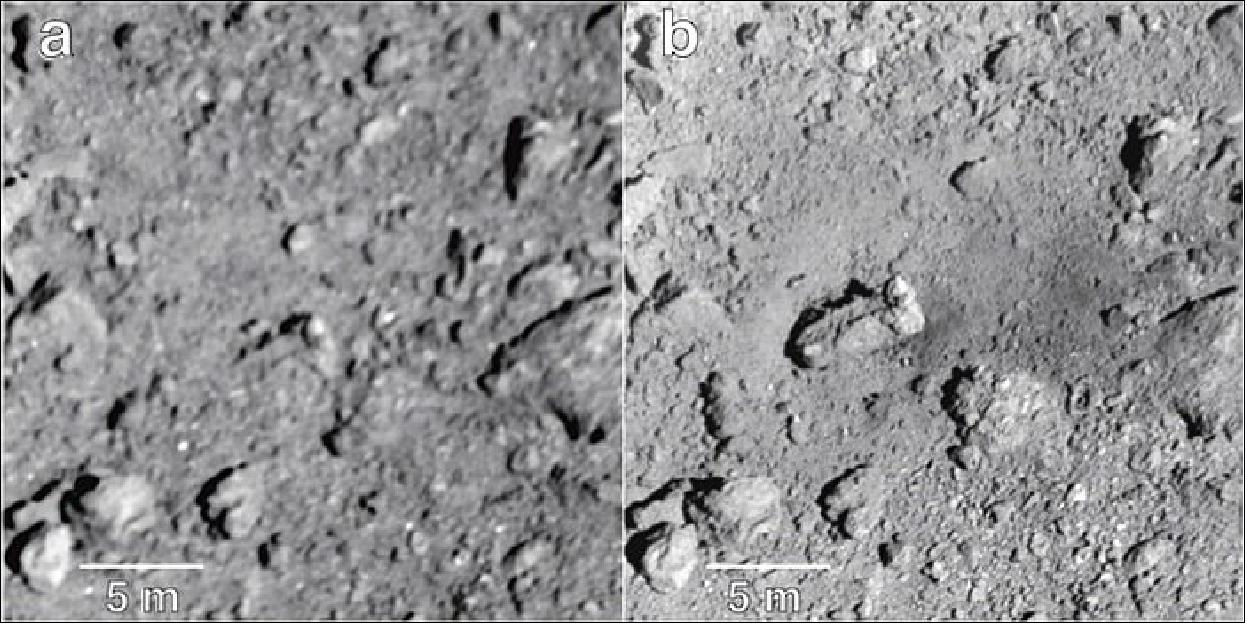

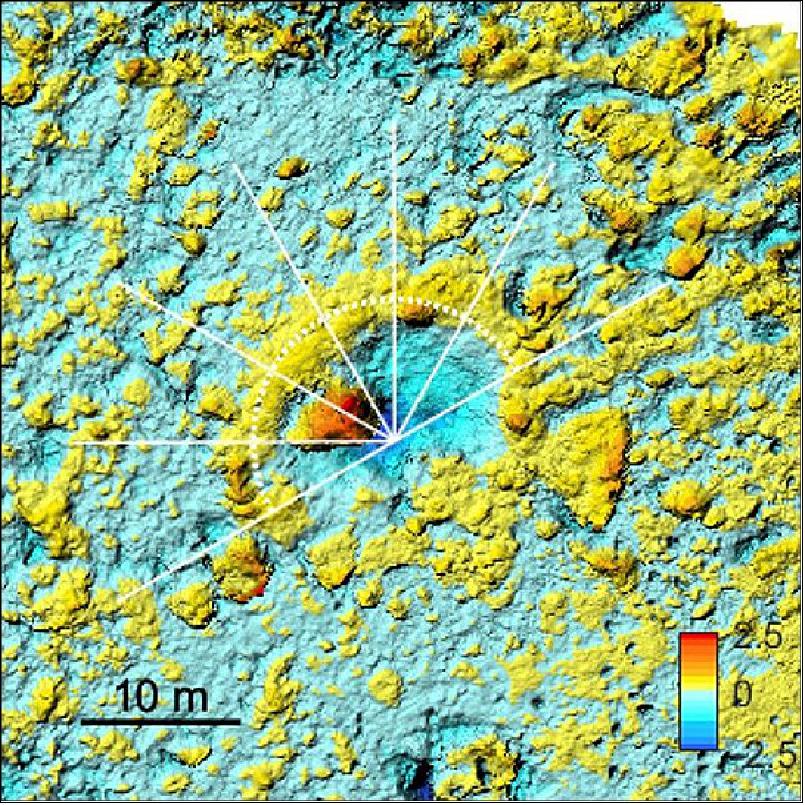

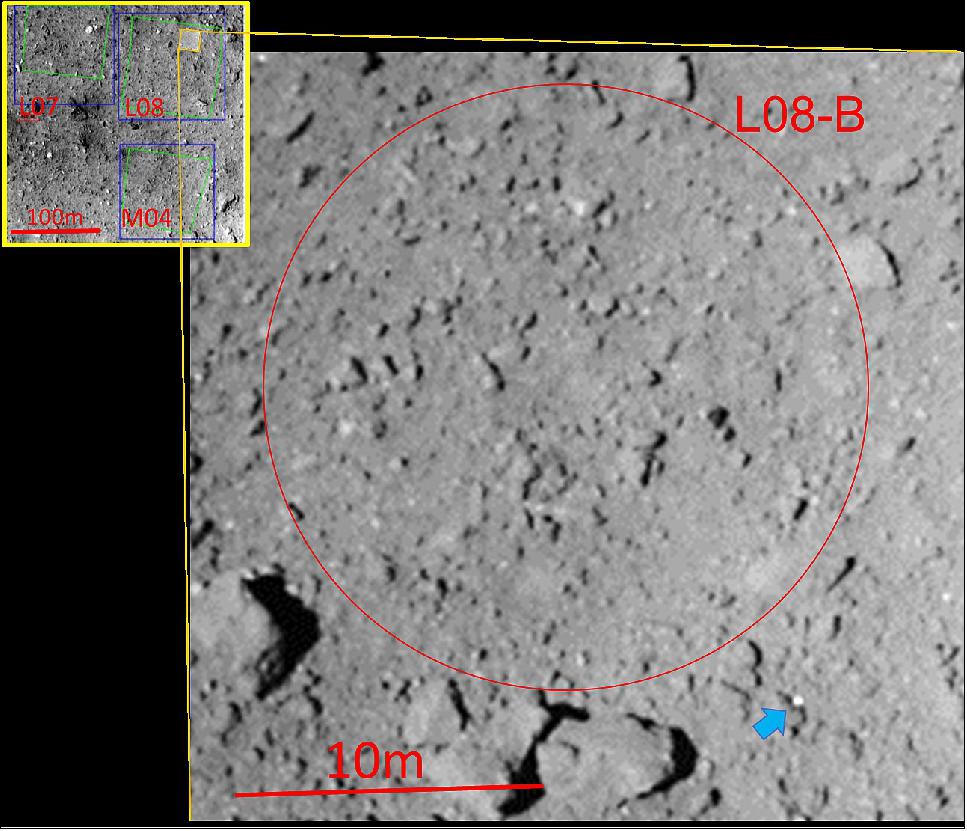

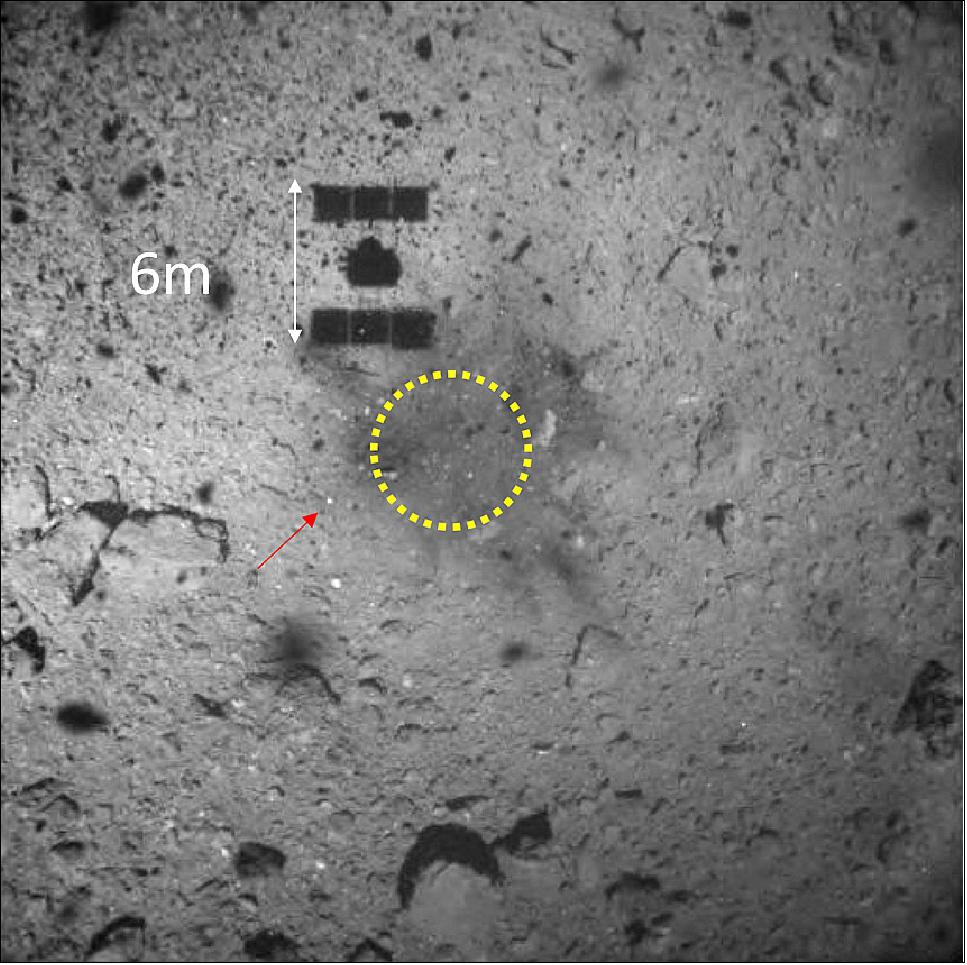

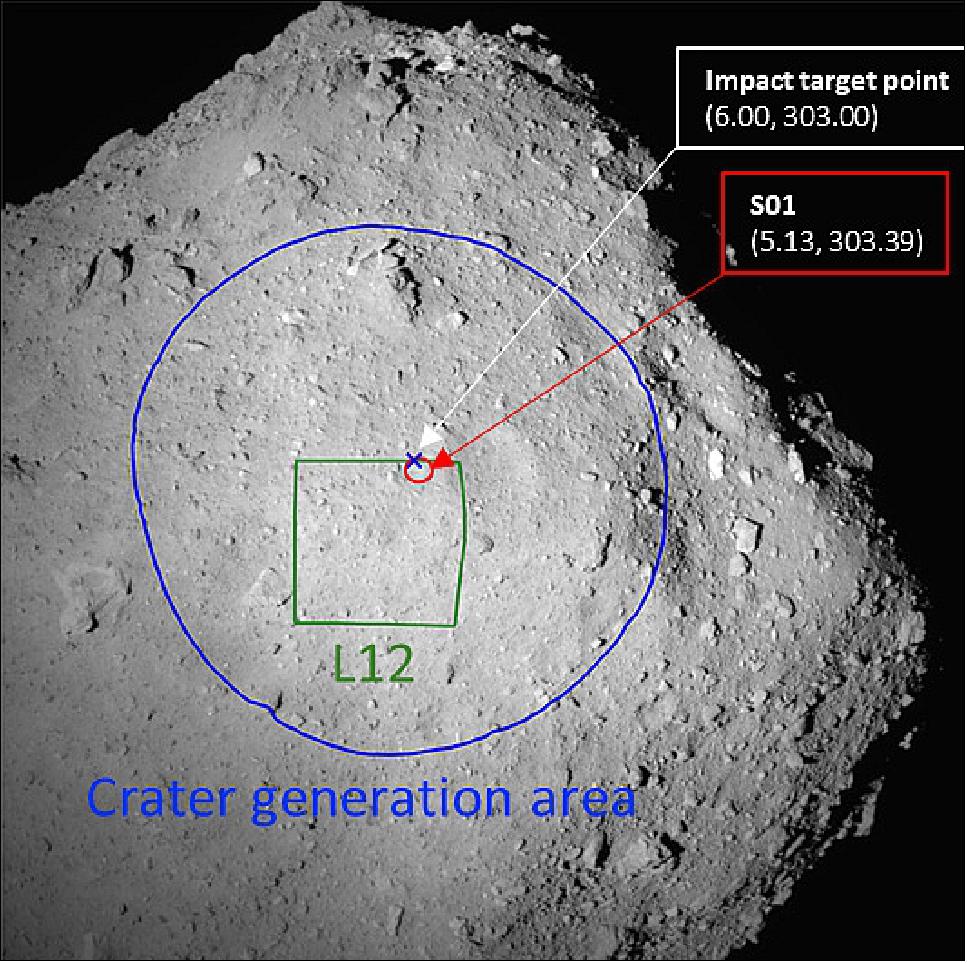

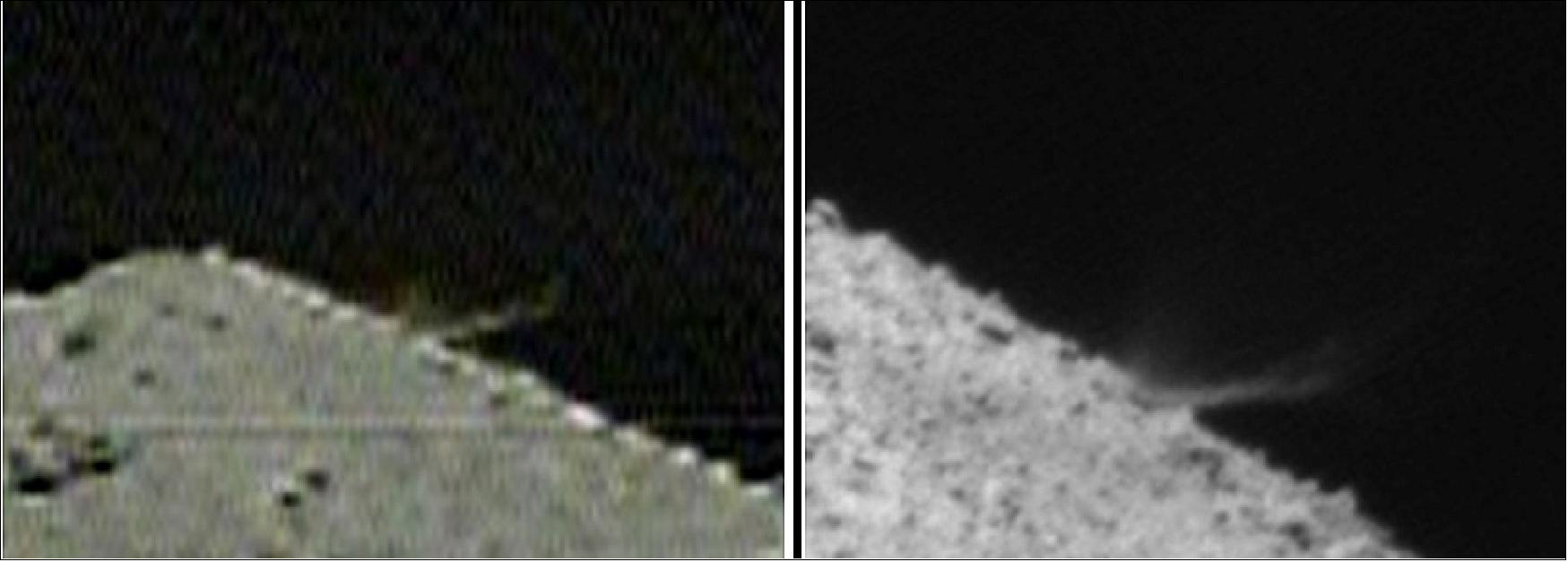

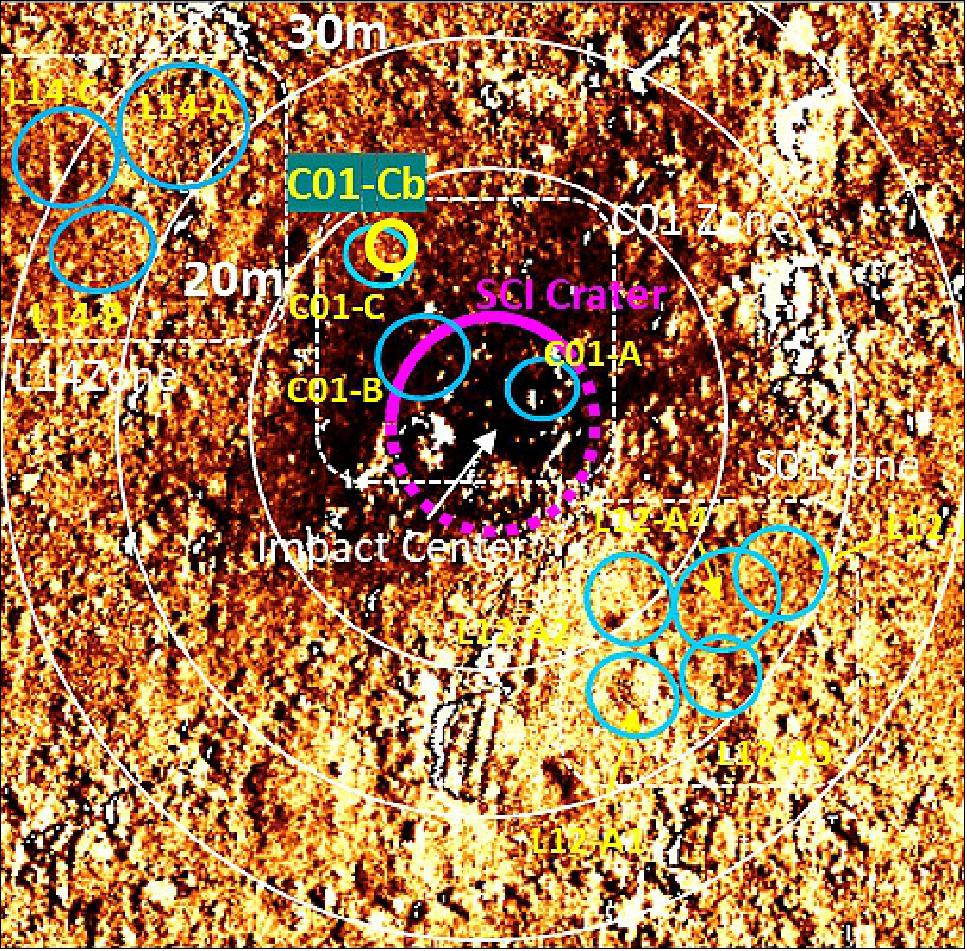

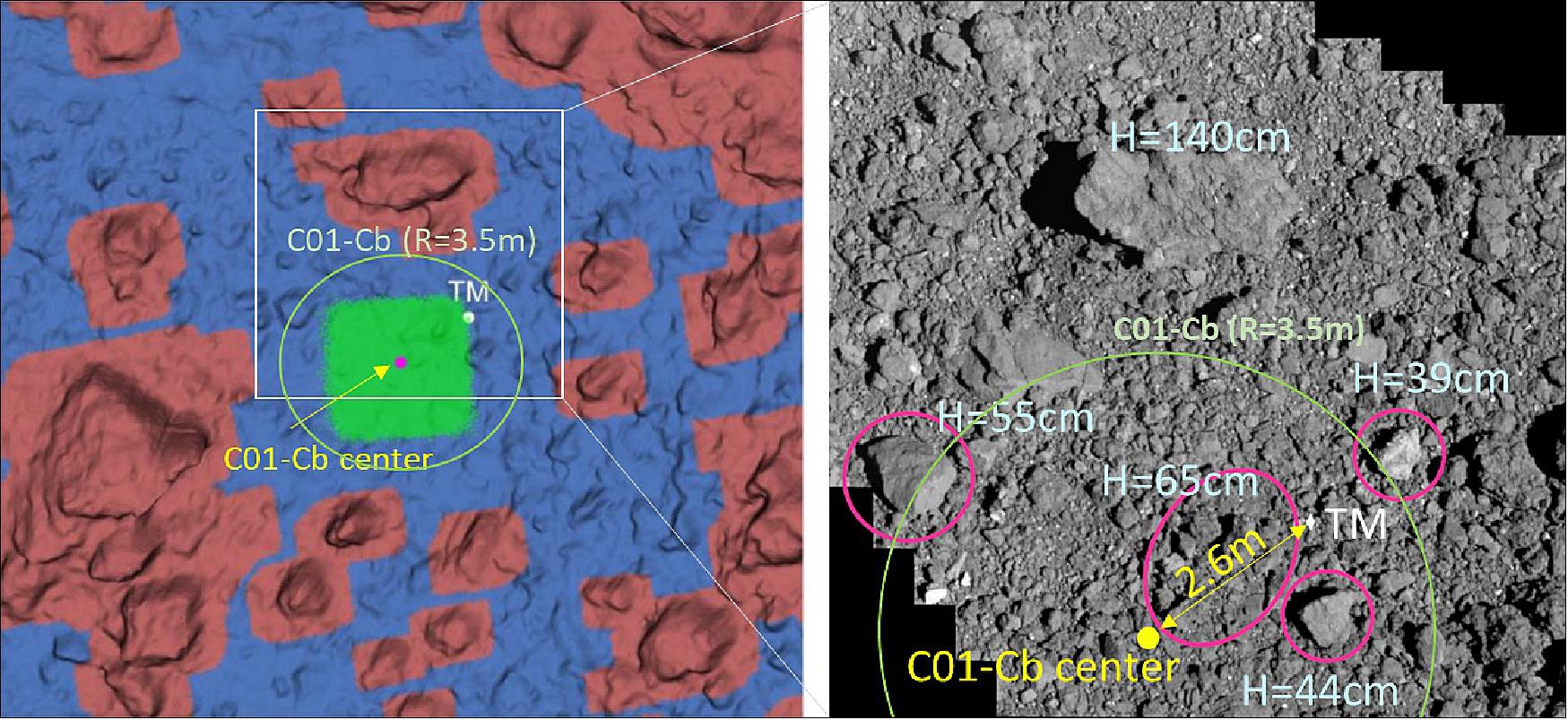

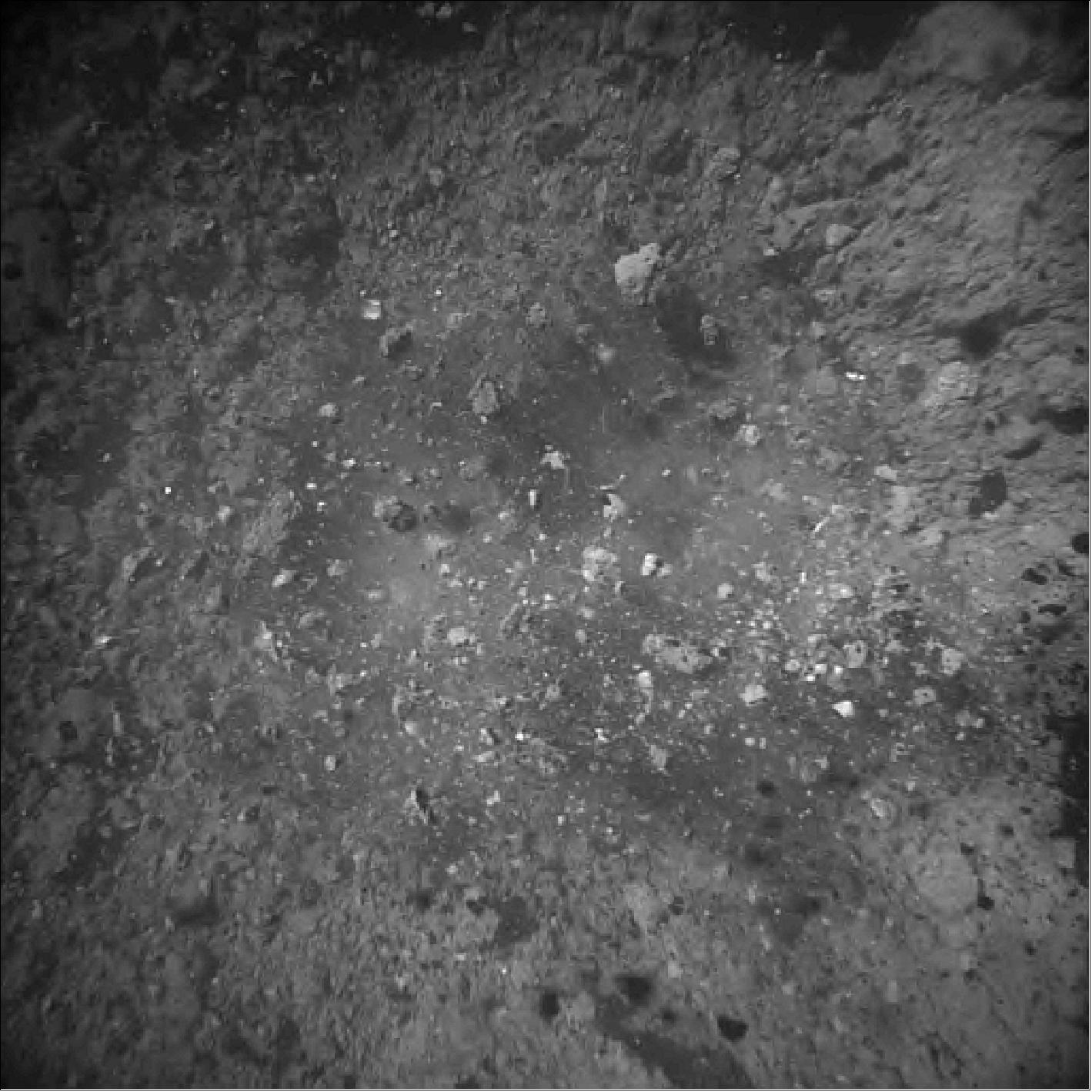

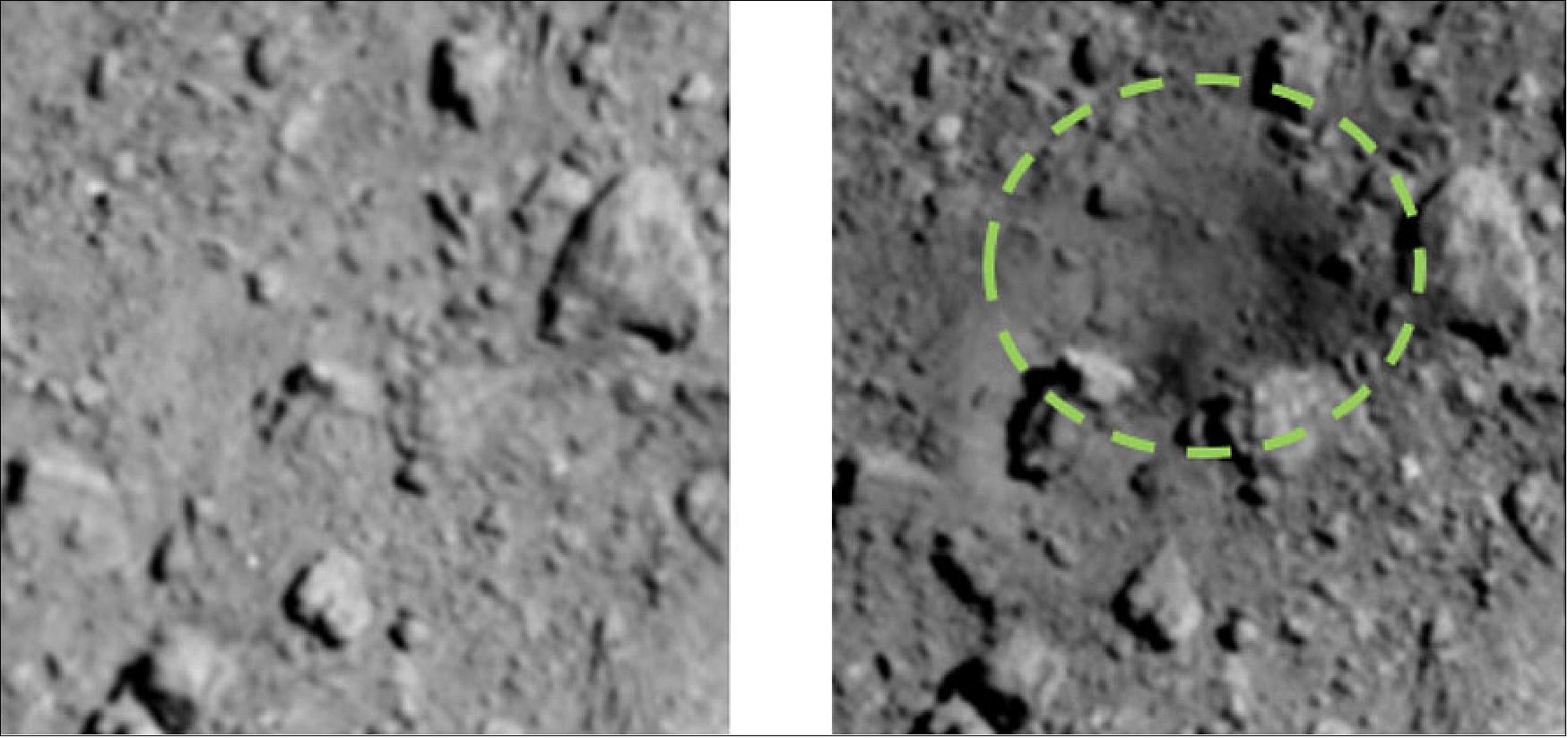

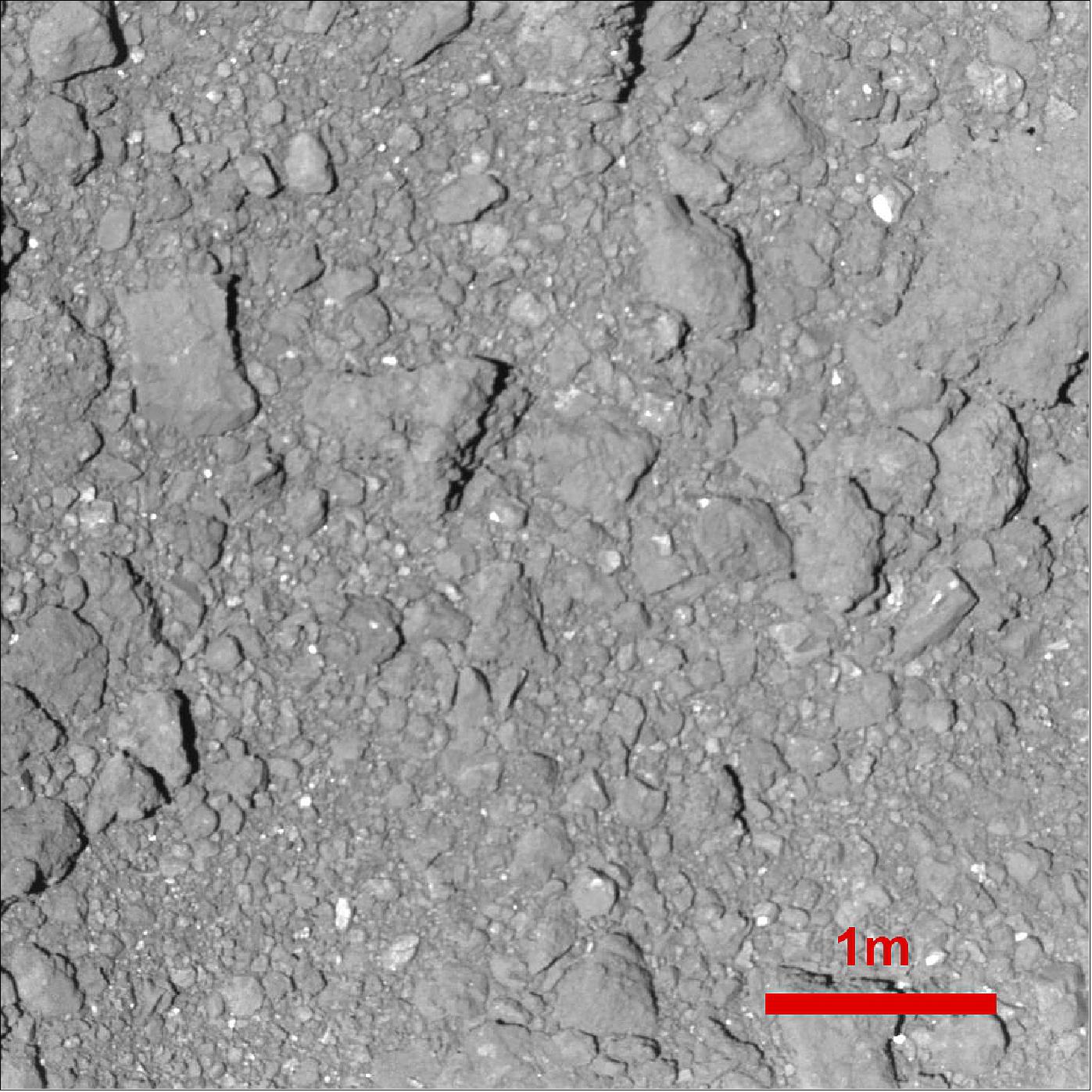

• October 30, 2020: The artificial impactor disturbed boulders within a 30m radius from the center of the impact crater- providing important insight into asteroids’ resurfacing processes. 24)

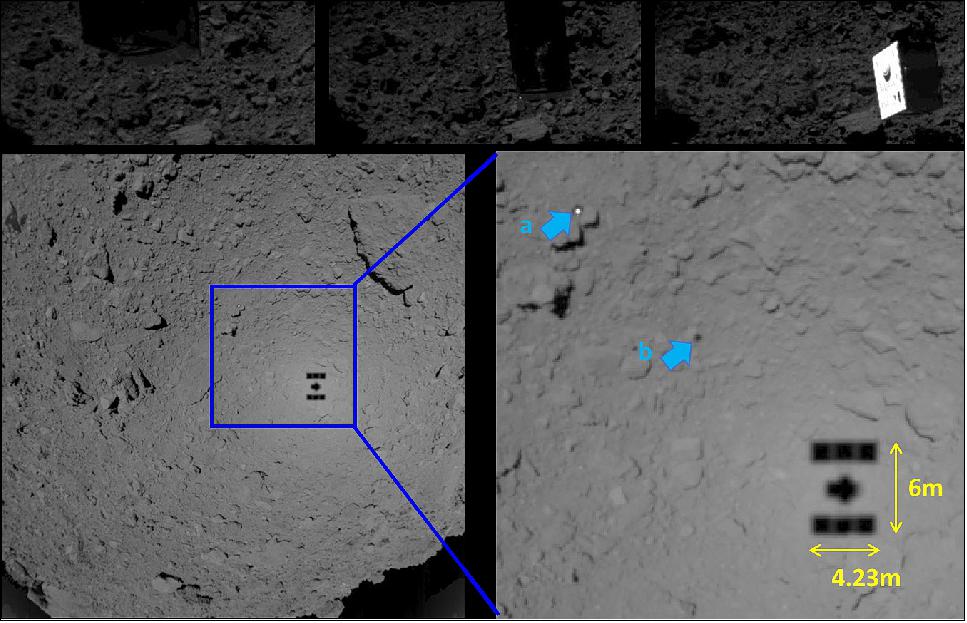

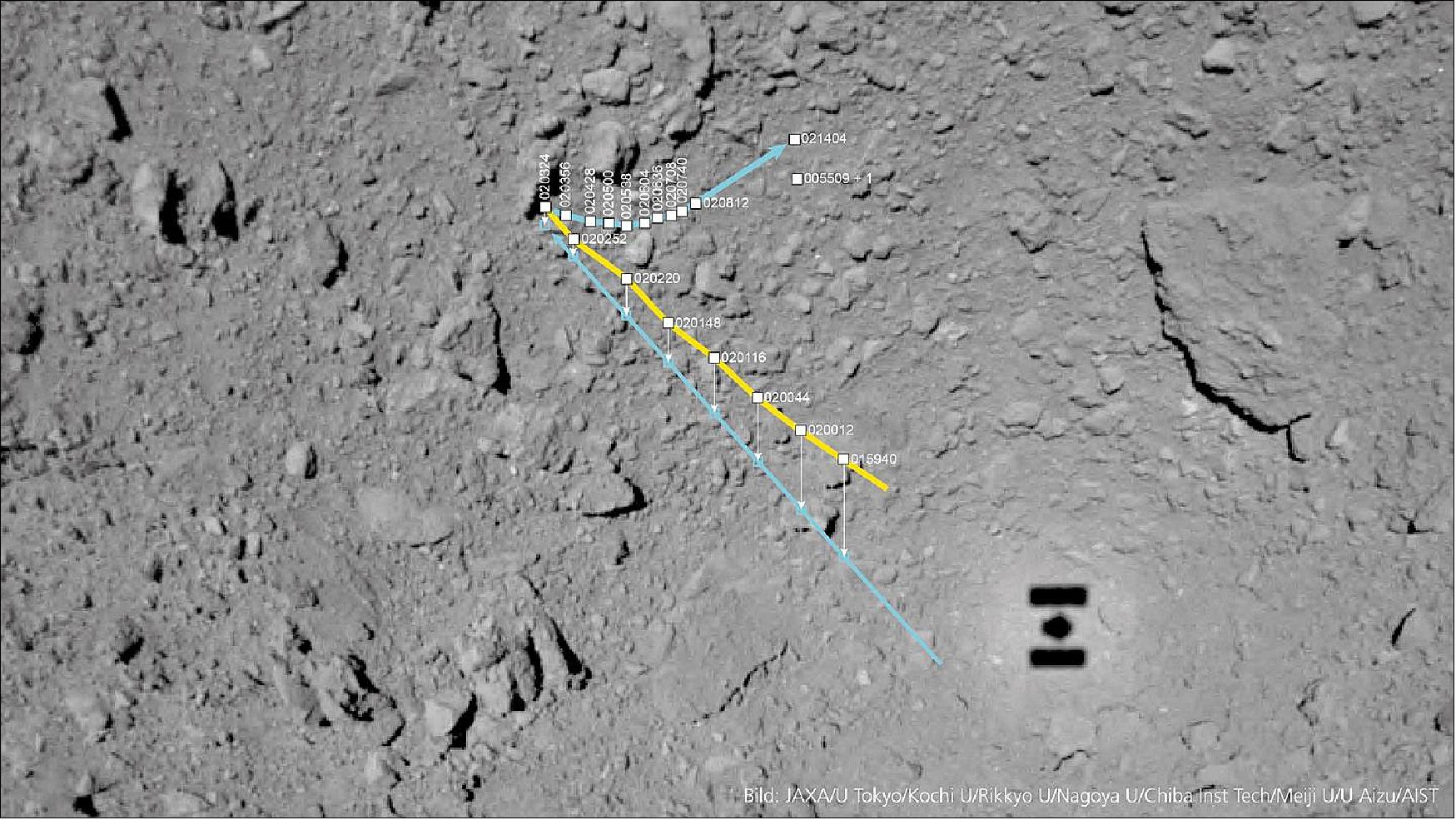

- Professor Masahiko Arakawa (Graduate School of Science, Kobe University, Japan) and members of the Hayabusa-2 mission discovered more than 200 boulders ranging from 30 cm to 6 m in size, which either newly appeared or moved as a result of the artificial impact crater created by Japanese spacecraft Hayabusa2’s SCI (Small Carry-on Impactor) on April 5th, 2019. Some boulders were disturbed even in areas as far as 40 m from the crater center. The researchers also discovered that the seismic shaking area, in which the surface boulders were shaken and moved an order of cm by the impact, extended about 30 m from the crater center. Hayabusa2 recovered a surface sample at the north point of the SCI crater (TD2), and the thickness of ejecta deposits at this site were estimated to be between 1.0 mm to 1.8 cm using a Digital Elevation Map (DEM). These findings on a real asteroid’s resurfacing processes can be used as a benchmark for numerical simulations of small body impacts, in addition to artificial impacts in future planetary missions such as NASA’s Double Asteroid Redirection Test (DART). The results will be presented at the 52nd meeting of the AAS Division of Planetary Science on October 29th in the session entitled Asteroids: Bennu and Ryugu 2.

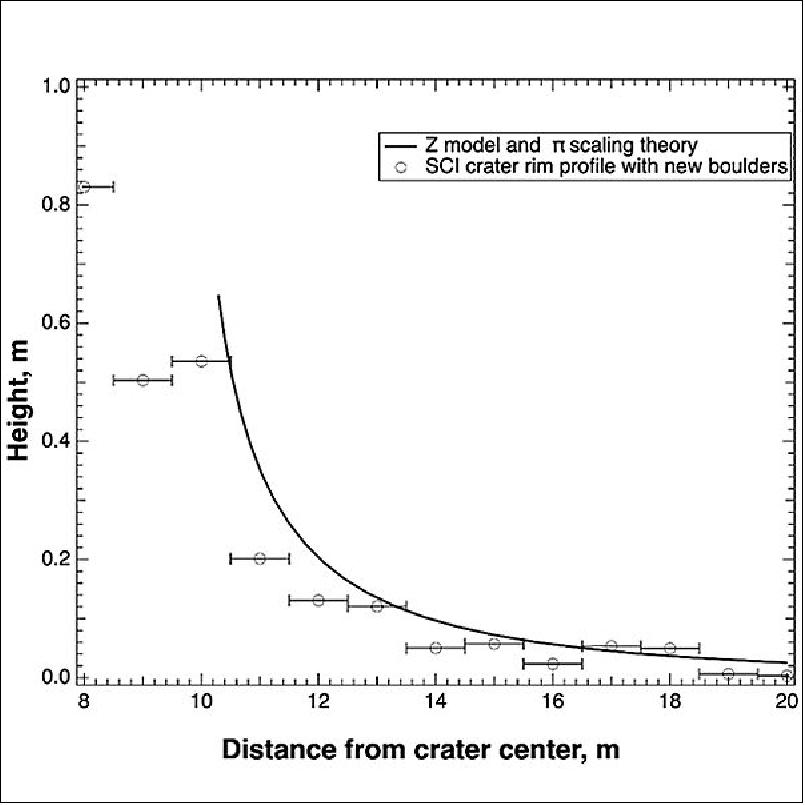

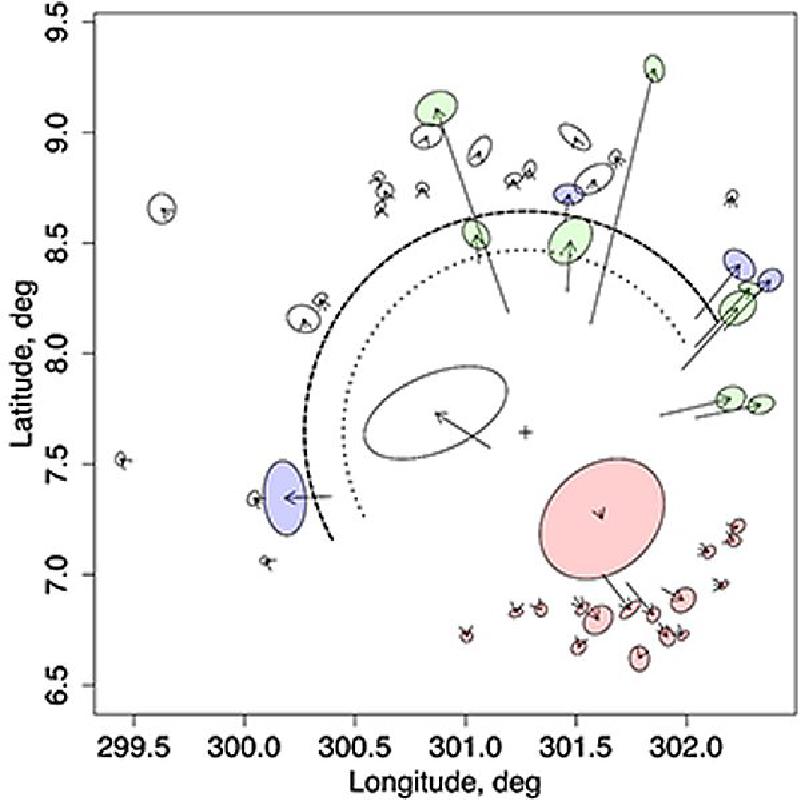

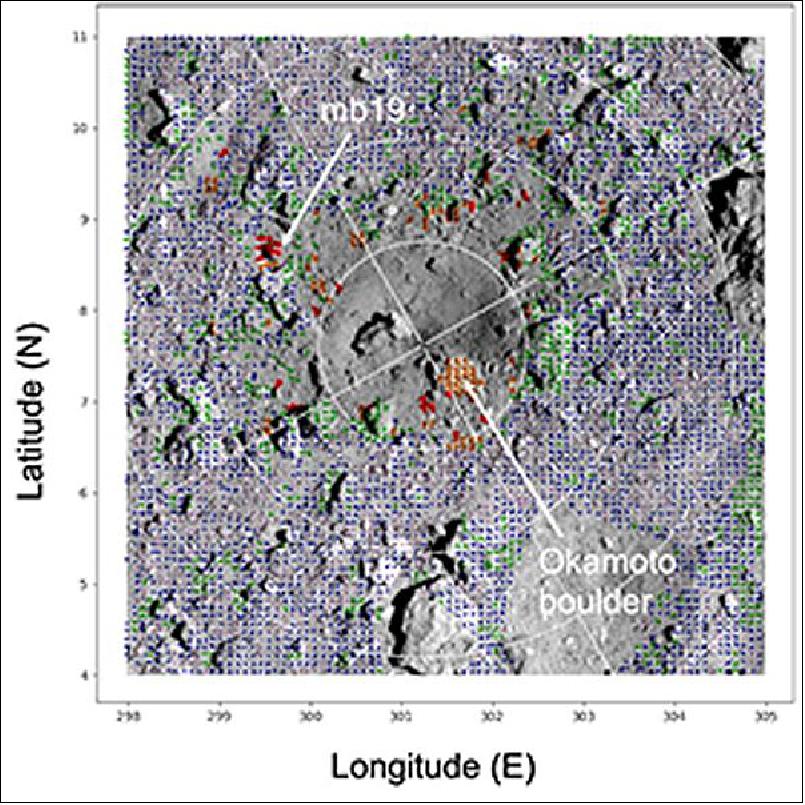

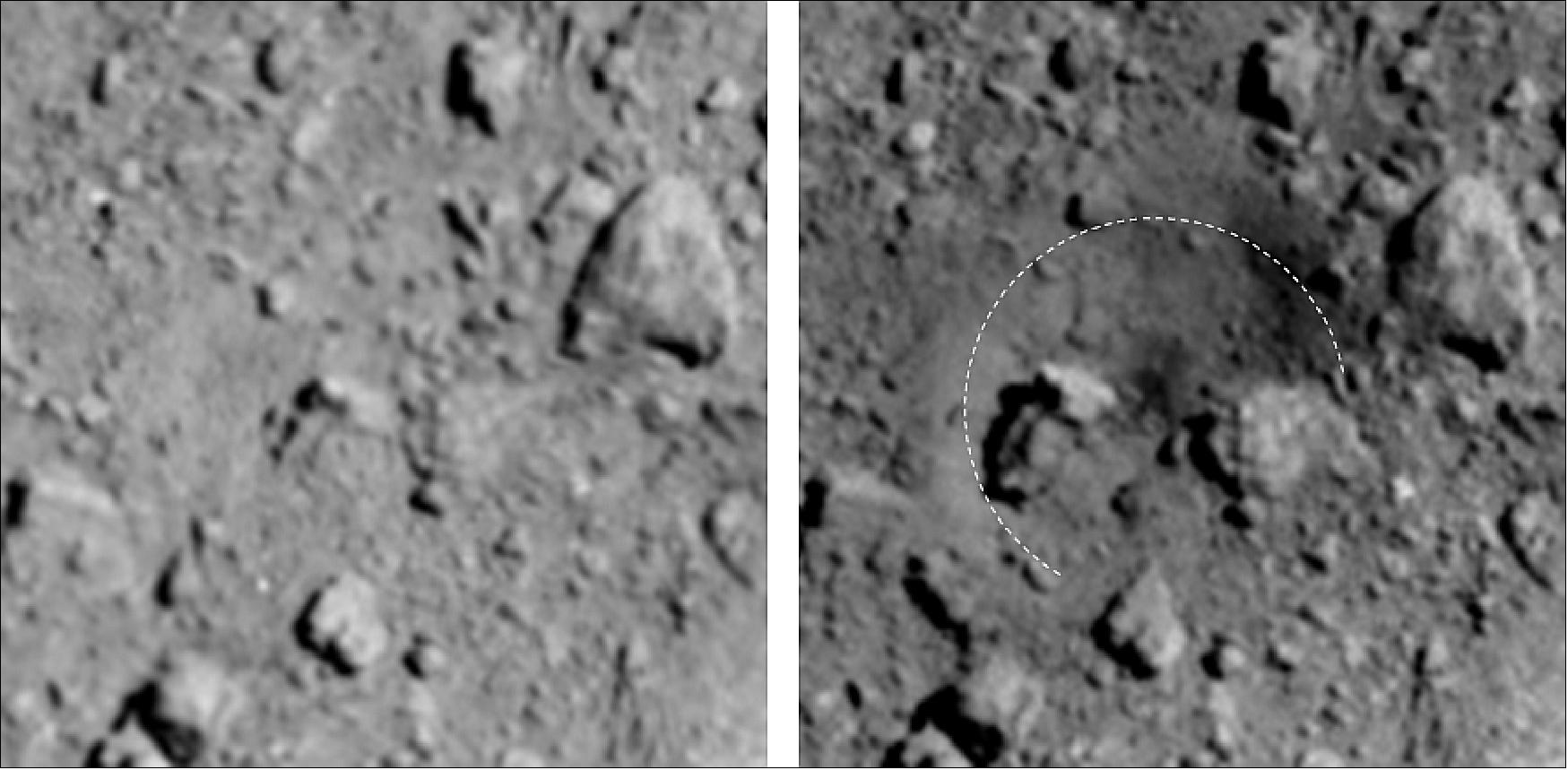

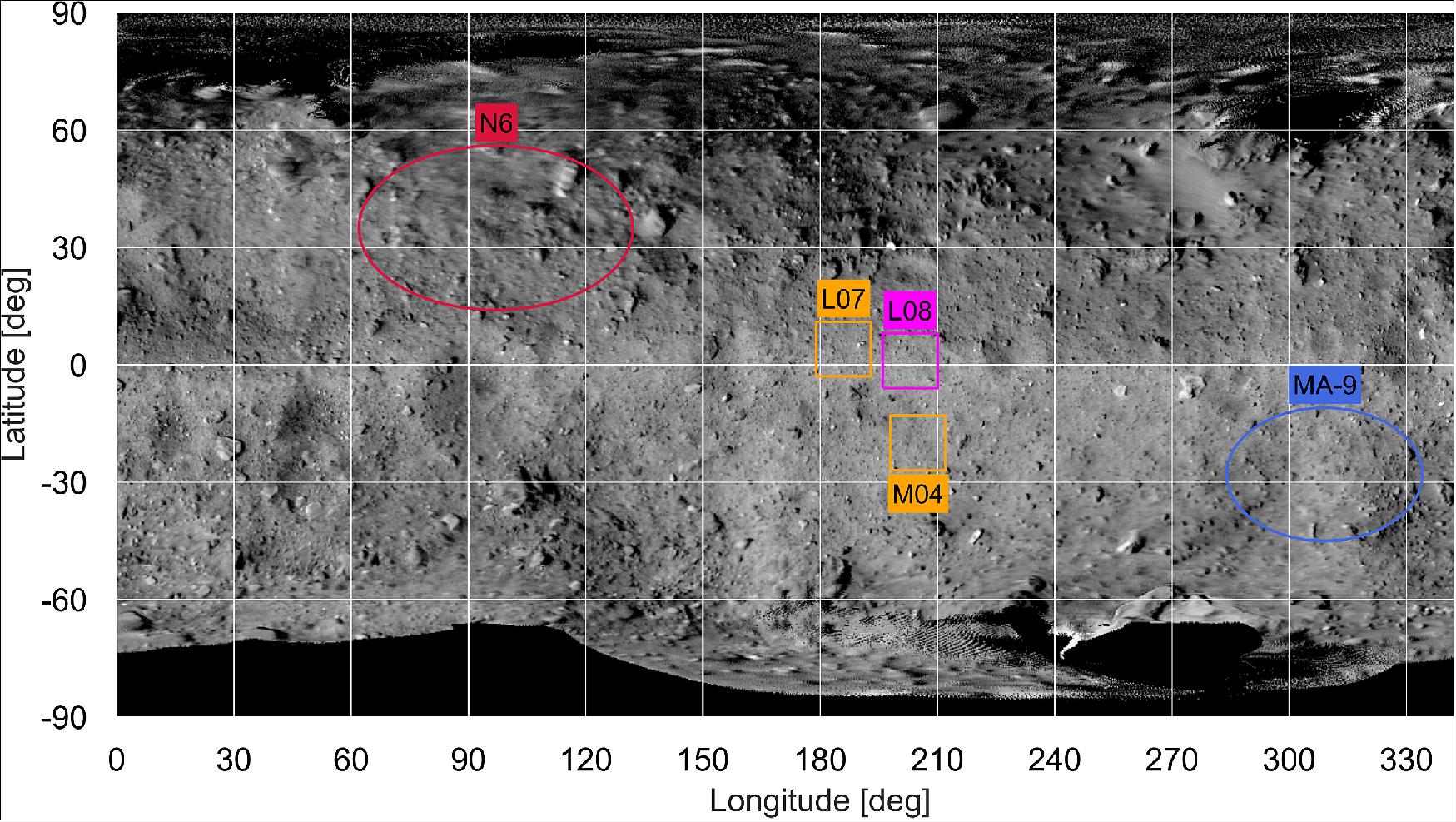

- The aim of impacting Ryugu with a ~13 cm SCI projectile was to recover a sample of the subsurface material. In addition, this provided a good opportunity to study the surface renewal processes (resurfacing) that result from an impact occurring on an asteroid with a surface gravity of 10-5 of the Earth’s gravity. The SCI succeeded in forming an impact crater, which was defined as a SCI crater with a diameter of 14.5 m (Arakawa et al., 2020), and the surface sample was recovered at TD2 (10.04°N, 300.60°E) (Figure 17). It was discovered that the crater center’s concentric area, which has a radius four times larger than the crater radius, was also disturbed by the SCI impact, causing boulder movement.

- The researchers subsequently compared surface images before and after the artificial impact in order to study the resurfacing processes associated with cratering, such as seismic shaking and ejecta deposition. To do this, they constructed SCI crater rim profiles using a Digital Elevation Map (DEM) consisting of the pre-impact DEM subtracted from the post-impact DEM (Figure 18). The average rim profile was approximated by the empirical equation of h=hr e[-(r/R rim - 1)/λrim] and the fitted parameters of hr and λrim were 0.475 m and 0.245 m, respectively. Based on this profile, the SCI crater’s ejecta blanket thickness was calculated and found to be thinner than that of the conventional result for natural craters, as well as that calculated from the crater formation theory. However, this discrepancy was solved by accounting for the effect of the boulders that appeared on the post-impact images because the crater rim profiles derived from the DEMs might fail to detect these new boulders (Figure 19). According to this crater rim profile, the thickness of the ejecta deposits at TD2 were estimated to be between 1.0 mm to 1.8 cm.

- The 48 boulders in the post-impact image could be traced back to their initial positions in the pre-impact image, and it was found that the 1 m-sized boulders were ejected several meters outside of the crater. They were classified into the following four groups according to their motion mechanisms: 1. excavation flow, 2. pushed by falling ejecta, 3. surface deformation dragged by the slight movement of the Okamoto boulder, and 4. seismic shaking caused by the SCI impact itself (Figure 20). In all groups, the motion vectors of these boulders seemed to radiate from the crater center.

- The 169 new boulders ranging from 30 cm to 3 m in size were found only in the post-impact images, and they were distributed up to ~40 m from the crater center. The histogram of the number of new boulders was studied in each radial width of 1m at a distance of 9–45 m from the crater center, with the maximum number of boulders being found at a distance of 17 m. Beyond 17 m, the number of boulders decreased in accordance with the increase in distance from the crater center.

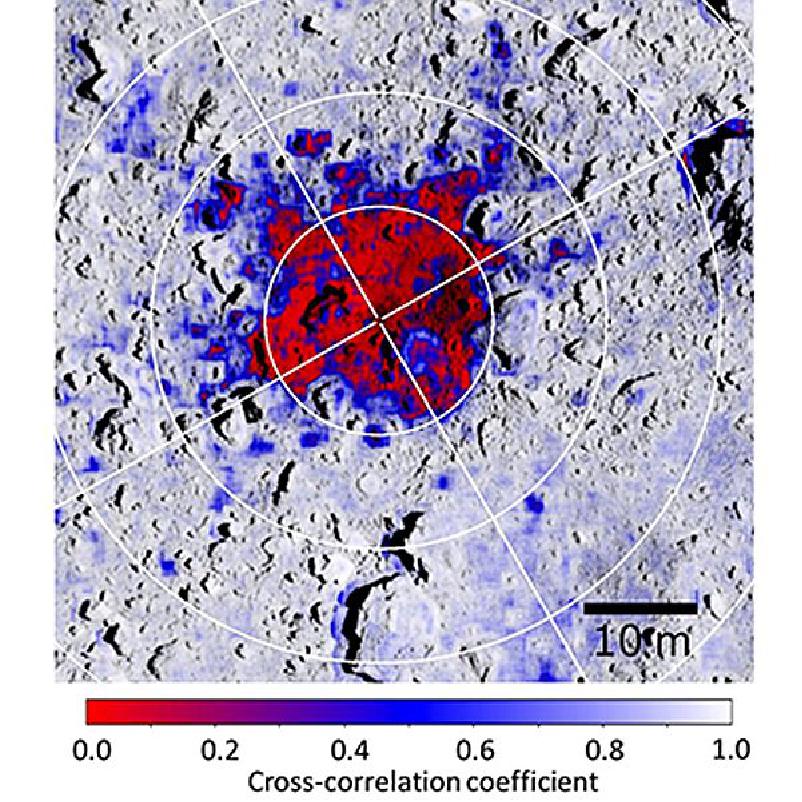

- To investigate this further, a correlation coefficient evaluation between the pre- and post-impact images was carried out. It was discovered that the low cross-correlation coefficient region outside the SCI crater has an asymmetric structure (Figure 21), which is very similar to the area around the impact point where ejecta were deposited (Arakawa et al., 2020, Ref. 25). Based on a template matching method using the correlation coefficient evaluation, the boulder displacements with cross-correlation coefficients above 0.8 were derived with a resolution of ~1 cm. This indicated that these displacements could be caused by the seismic shaking (Figure 22). Boulders were moved by more than 3cm in the area close to the SCI crater. This disturbance spans an area up to 15 m from the impact, with the motion vectors radiating out from the crater center. Disturbed areas that were displaced by 10 cm still exist in the regions farther than 15 m from the center, however they appeared as patches of a few meters in size and were distributed randomly. Furthermore, the direction of these motion vectors in the distant regions was almost random and there was no clear evidence indicating the radial direction from the crater center. 25)

- Displacements larger than 3 cm were detected within a 15 m distance with a probability of more than 50%, and between 15 m and 30 m with a probability of approximately 10%. Therefore, Arakawa et al. propose, in accordance with Matsue et al. (2020)’s experimental results, that the seismic shaking caused most of the area’s boulders to move at a maximum acceleration 7 times larger than Ryugu’s surface gravity (gryugu). Furthermore, they also discovered that the impact moved boulders at a maximum acceleration of between 7gryugu and 1gryugu in about 10% of the area. It is hoped that these results will inform future numerical simulations of small body collisions, as well as planetary missions involving artificial impacts.

• August 19, 2020: On August 10, 2020, JAXA was informed that the Authorization of Return of Overseas-Launched Space Object (AROLSO) for the re-entry capsule from Hayabusa-2 was issued by the Australian Government. The date of the issuance is August 6, 2020. 26)

- The Hayabusa2 reentry capsule will return to Earth in South Australia on December 6, 2020 (Japan Time and Australian Time). The landing site will be the Woomera Prohibited Area. The issuance of the AROLSO gave a major step forward for the capsule recovery.

- We will continue careful operation for return of Hayabusa-2 and recovery of the capsule, and the operation status will be announced in a timely manner.

- Comment from JAXA President, Hiroshi Yamakawa: The approval to carry out the re-entry and recovery operations of the Hayabusa-2 return sample capsule is a significant milestone. We would like to express our sincere gratitude for the support of the Australian Government as well as multiple organizations in Australia for their cooperation. We will continue to prepare for the successful mission in December 2020 in close cooperation with the Australian Government.

• July 14, 2020: Dr. Hiroshi Yamakawa, President, the Japan Aerospace Exploration Agency (JAXA) and Dr. Megan Clark AC, Head, the Australian Space Agency (the Agency) released a joint statement dated July 14 2020. The statement acknowledges that the capsule of ‘Hayabusa2’ containing the asteroid samples will land in South Australia on December 6, 2020. 27)

- JAXA and the Agency are working through JAXA’s plan for the re-entry and recovery of the capsule. The plan will be finalized by the issuance of Authorization of Return of Overseas Launched Space Object (AROLSO) from the Australian government.

- Joint Statement for Cooperation in the Hayabusa-2 Sample Return Mission by the Australian Space Agency and the Japan Aerospace Exploration Agency, 14 July 2020

- The Australian Space Agency (the Agency) and the Japan Aerospace Exploration Agency (JAXA) have been in close cooperation on JAXA’s asteroid sample-return mission, ‘Hayabusa-2’. The sample capsule is planned to land in Woomera, South Australia and the Agency and JAXA are working towards the planned safe re-entry and recovery of the capsule containing the asteroid samples.

- Recently, JAXA indicated that 6 December 2020 (Australia/Japan time) is its planned target date for the capsule re-entry and recovery. The Agency and JAXA are working through JAXA’s application for Authorization of Return of Overseas Launched Space Object (AROLSO), which will need to be approved under the Space Activities Act (1998).

- Successfully realizing this epoch-making sample return mission is a great partnership between Australia and Japan and will be a symbol of international cooperation and of overcoming the difficulties and crisis caused by the pandemic.

• May 13, 2020: The 2nd ion engine operation has begun. This is an important operation in the return journey of Hayabusa-2 back to Earth. On May 12, 2020, the ion engine ignited at 07:00 (onboard time, JST) and was confirmed to be operating stably at 07:25 (ground time, JST). Currently, only a single ion engine is operating as the spacecraft is far from the Sun, and receives a low level of solar power with which to operate the ion engines. 28)

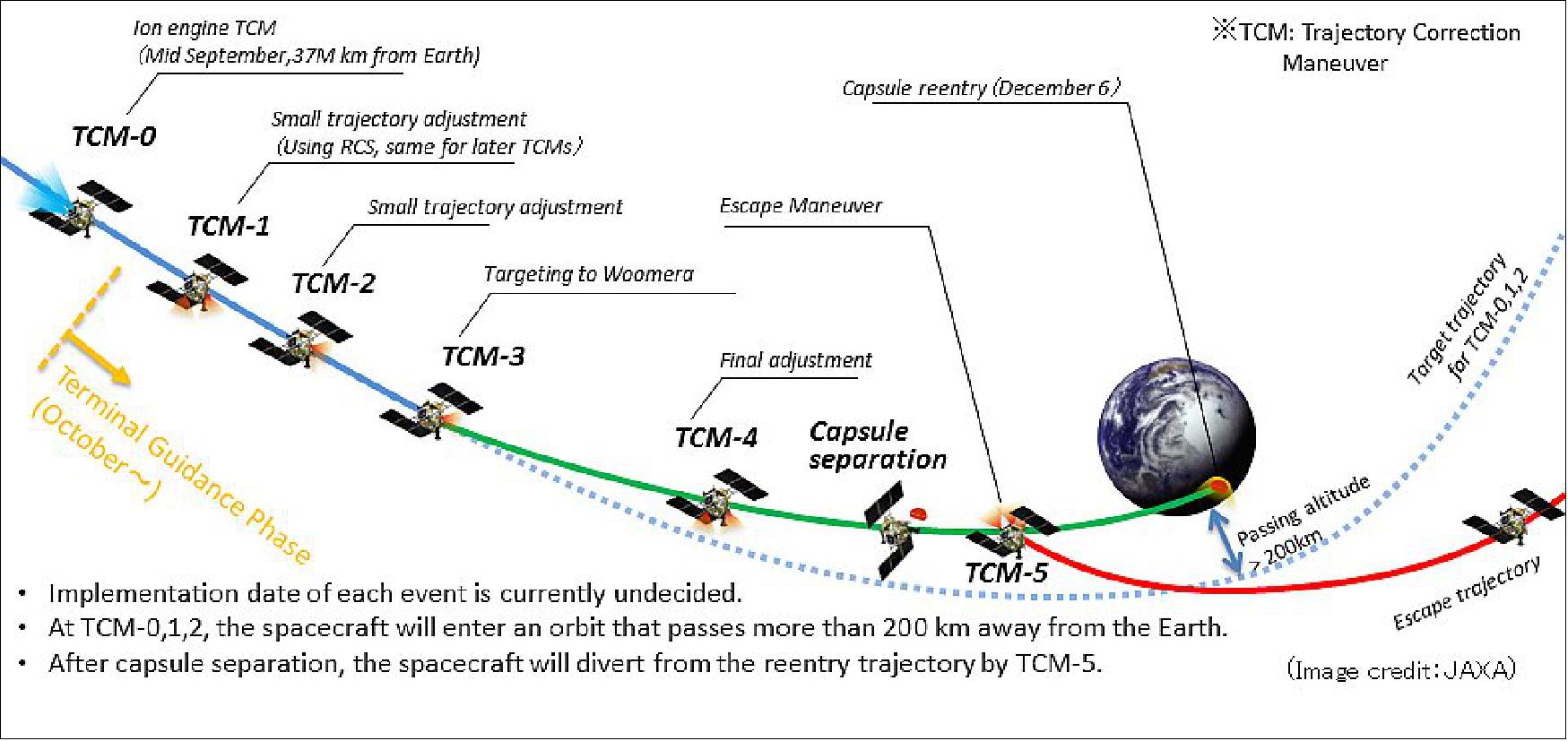

- The 2nd ion engine operation will continue until around September this year. At the end of the operation, the spacecraft will be in an orbit that can deliver the capsule to Earth. After that — from October of this year — we will perform precision guidance using the chemical thrusters (Figure 24).

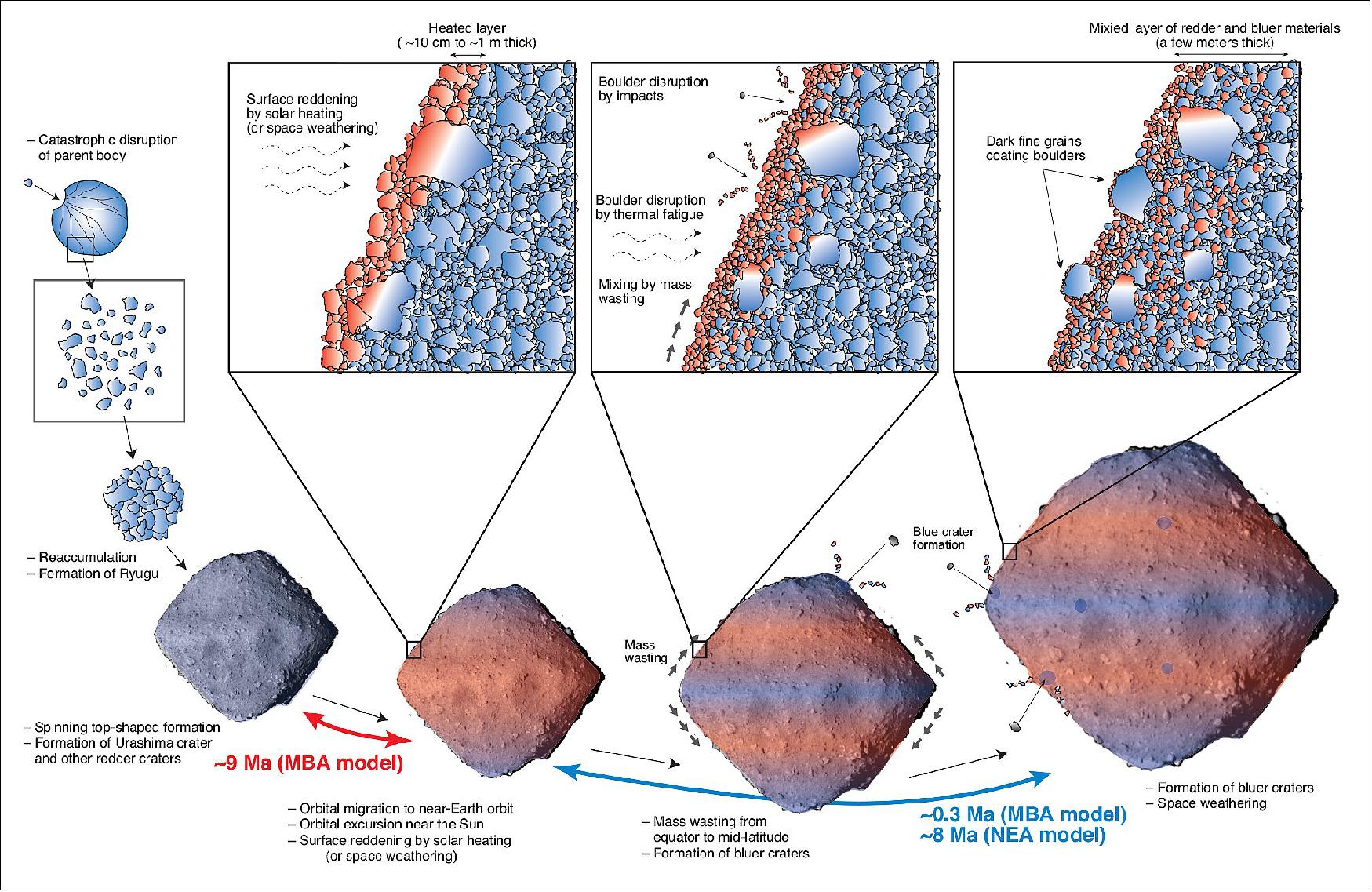

• May 11, 2020: In February and July of 2019, the Hayabusa-2 spacecraft briefly touched down on the surface of near-Earth asteroid Ryugu. The readings it took with various instruments at those times have given researchers insight into the physical and chemical properties of the 1-km-wide asteroid. These findings could help explain the history of Ryugu and other asteroids, as well as the solar system at large. 29)

- When our solar system formed around 5 billion years ago, most of the material it formed from became the sun, and a fraction of a percent became the planets and solid bodies, including asteroids. Planets have changed a lot since the early days of the solar system due to geological processes, chemical changes, bombardments and more. But asteroids have remained more or less the same as they are too small to experience those things, and are therefore useful for researchers who investigate the early solar system and our origins.

- “I believe knowledge of the evolutionary processes of asteroids and planets are essential to understand the origins of the Earth and life itself,” said Associate Professor Tomokatsu Morota from the Department of Earth and Planetary Science at the University of Tokyo. “Asteroid Ryugu presents an amazing opportunity to learn more about this as it is relatively close to home, so Hayabusa-2 could make a return journey relatively easily.”

- Hayabusa-2 launched in December 2014 and reached Ryugu in June 2018. At the time of writing, Hayabusa-2 is on its way back to Earth and is scheduled to deliver a payload in December 2020. This payload consists of small samples of surface material from Ryugu collected during two touchdowns in February and July of 2019. Researchers will learn much from the direct study of this material, but even before it reaches us, Hayabusa2 helped researchers to investigate the physical and chemical makeup of Ryugu.

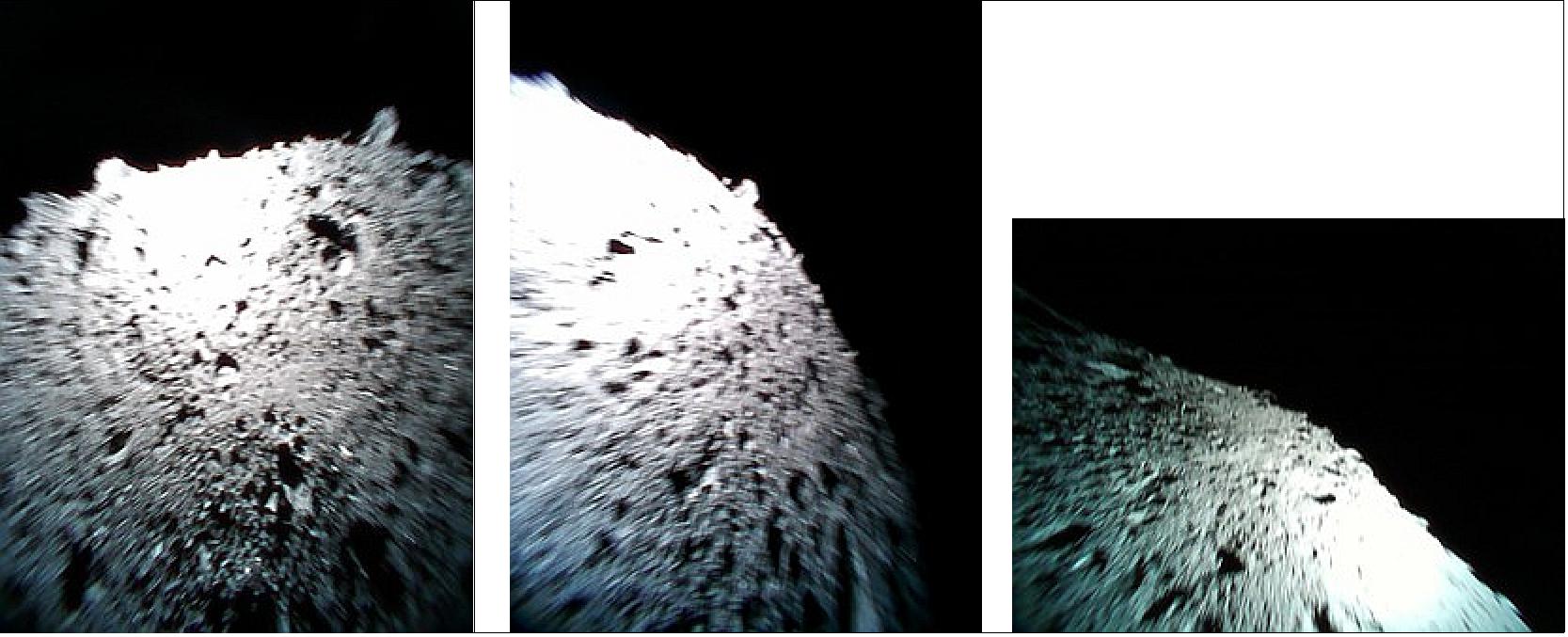

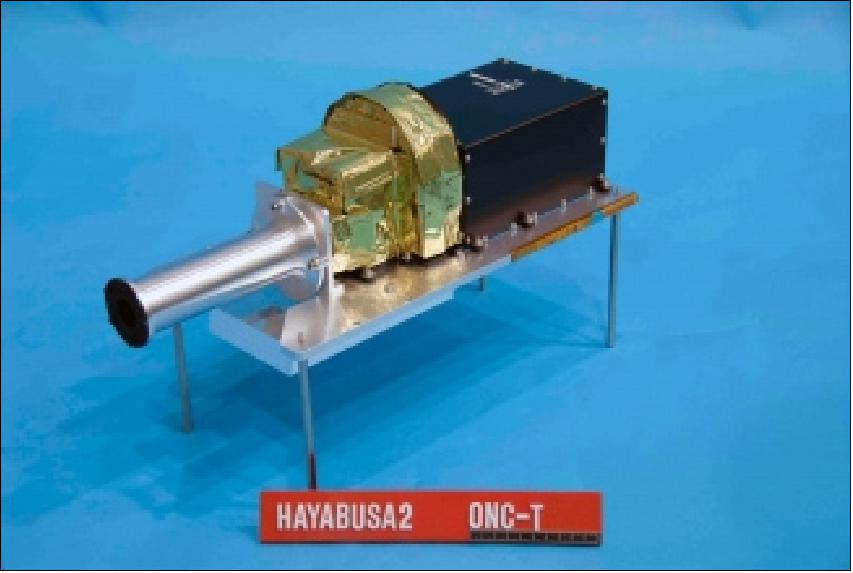

- “We used Hayabusa-2’s ONC-W1 and ONC-T imaging instruments to look at dusty matter kicked up by the spacecraft’s engines during the touchdowns,” said Morota. “We discovered large amounts of very fine grains of dark-red colored minerals. These were produced by solar heating, suggesting at some point Ryugu must have passed close by the sun.”

- Morota and his team investigated the spatial distribution of the dark-red matter around Ryugu as well as its spectra or light signature. The strong presence of the material around specific latitudes corresponded to the areas that would have received the most solar radiation in the asteroid’s past; hence, the belief that Ryugu must have passed by the sun.

- “From previous studies we know Ryugu is carbon-rich and contains hydrated minerals and organic molecules. We wanted to know how solar heating chemically changed these molecules,” said Morota. “Our theories about solar heating could change what we know of orbital dynamics of asteroids in the solar system. This in turn alters our knowledge of broader solar system history, including factors that may have affected the early Earth.”

- When Hayabusa-2 delivers material it collected during both touchdowns, researchers will unlock even more secrets of our solar history. Based on spectral readings and albedo, or reflectivity, from within the touchdown sites, researchers are confident that both dark-red solar-heated material and gray unheated material were collected by Hayabusa-2. Morota and his team hope to study larger properties of Ryugu, such as its many craters and boulders.

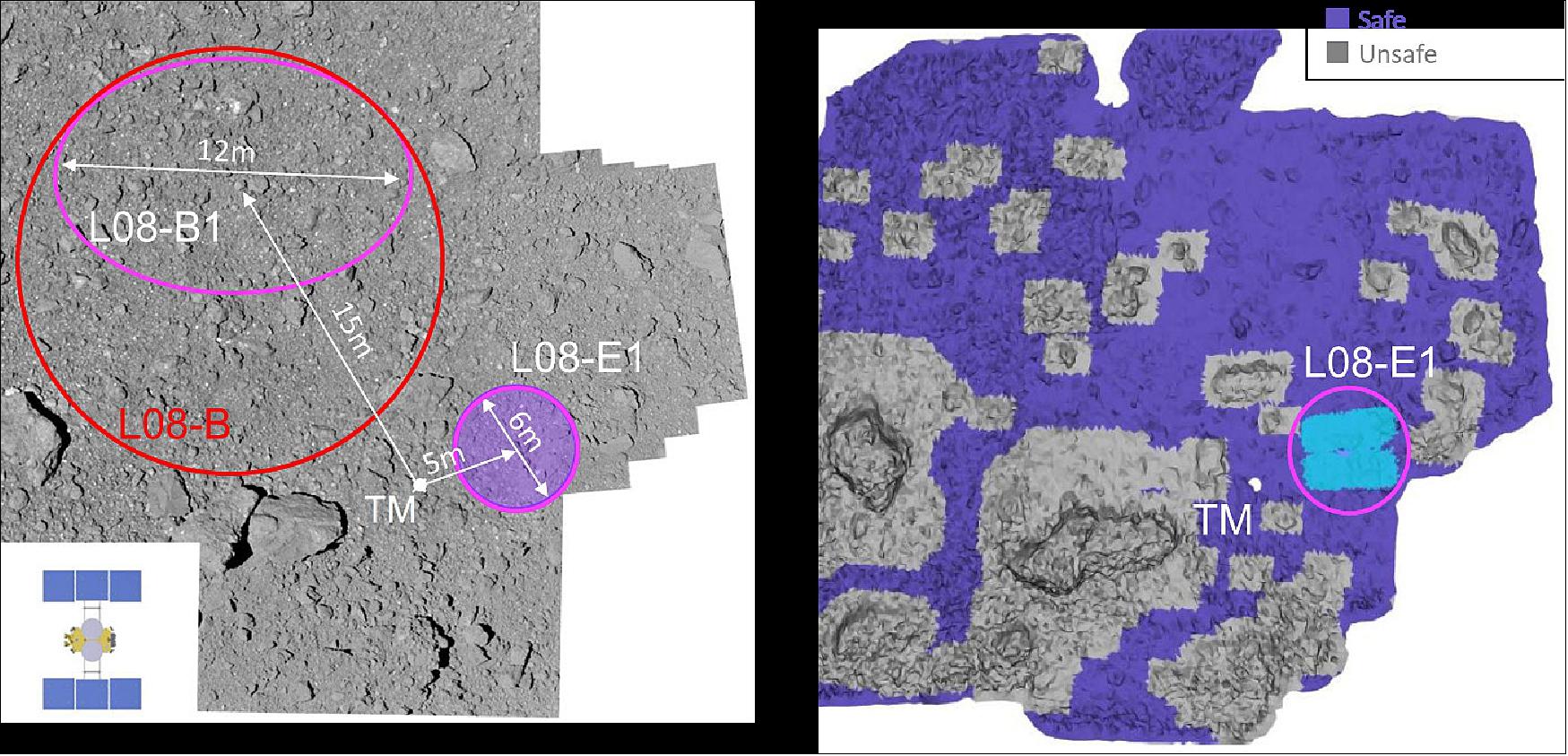

- “I wish to study the statistics of Ryugu’s surface craters to better understand the strength characteristics of its rocks, and history of small impacts it may have received,” said Morota. “The craters and boulders on Ryugu meant there were limited safe landing locations for Hayabusa-2. Finding a suitable location was hard work and the eventual first successful touchdown was one of the most exciting events of my life” (the paper is provided in Ref. 31).

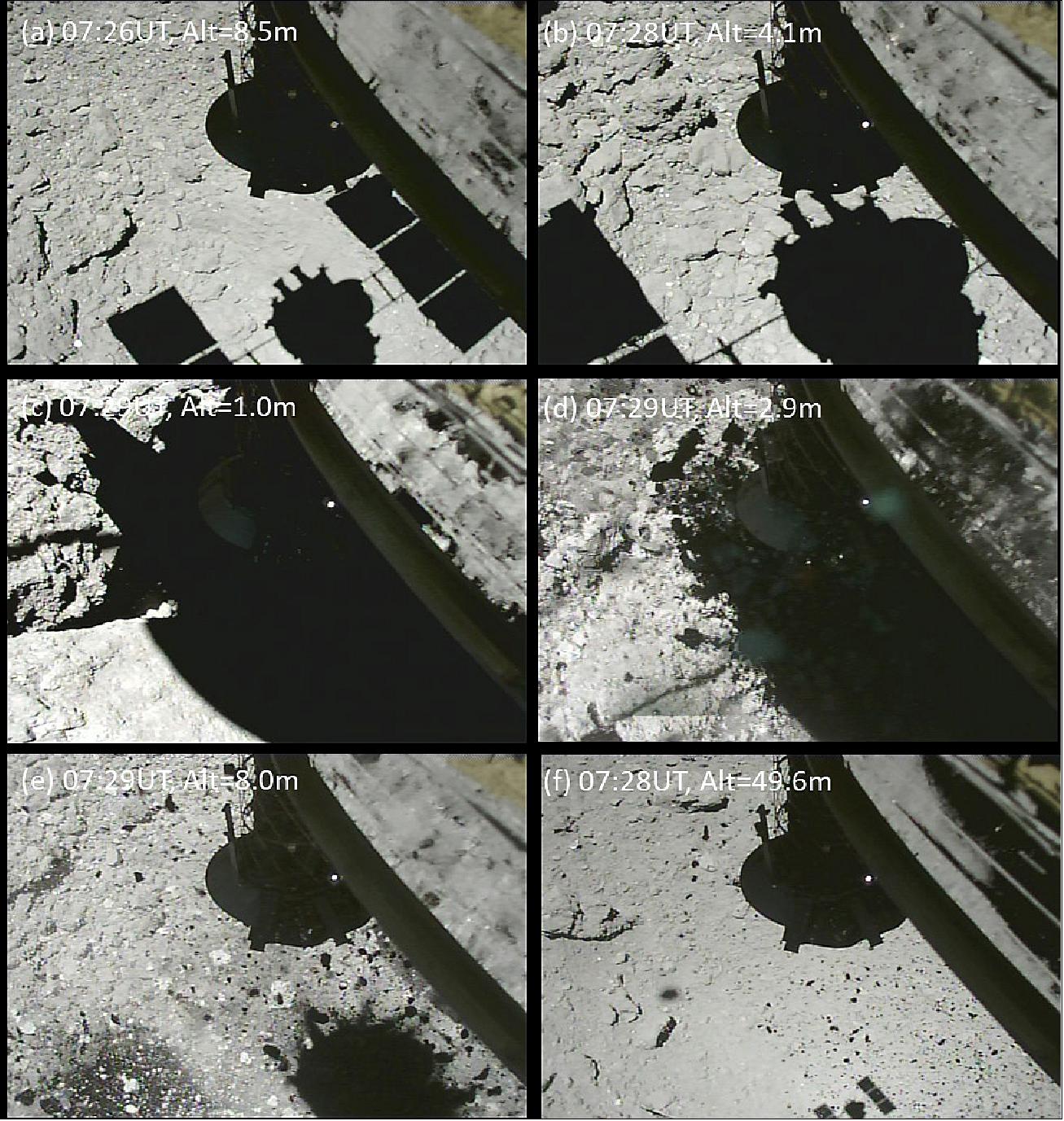

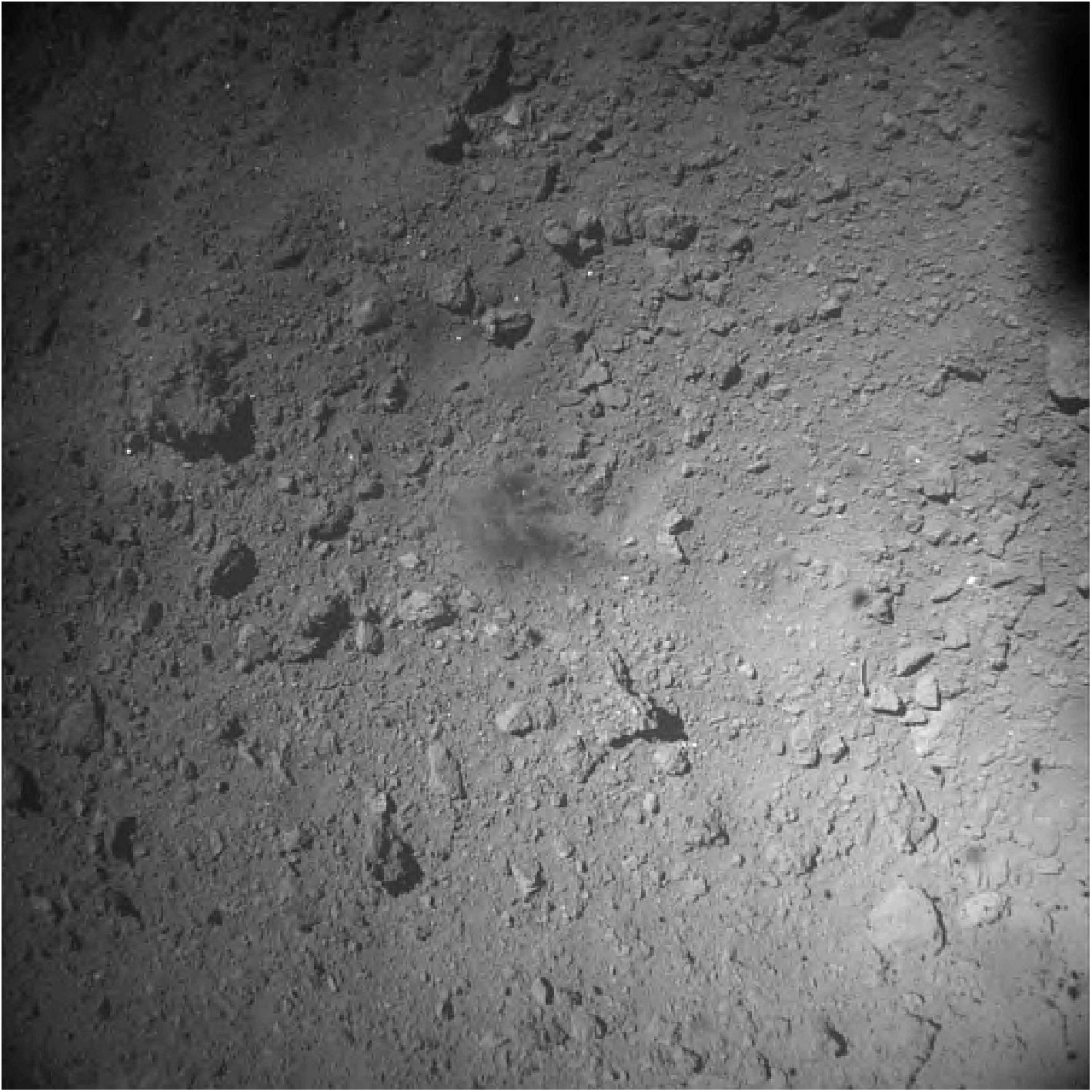

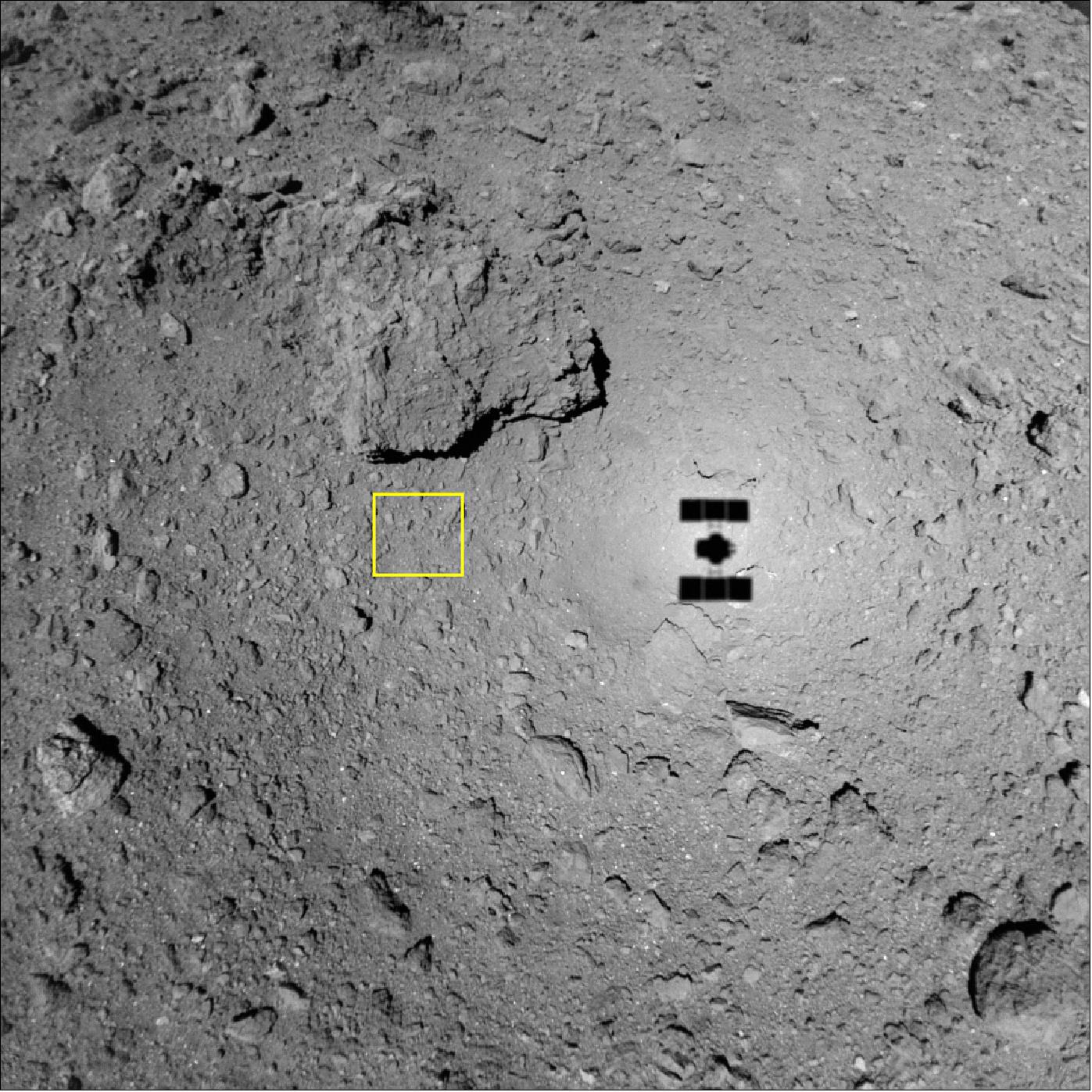

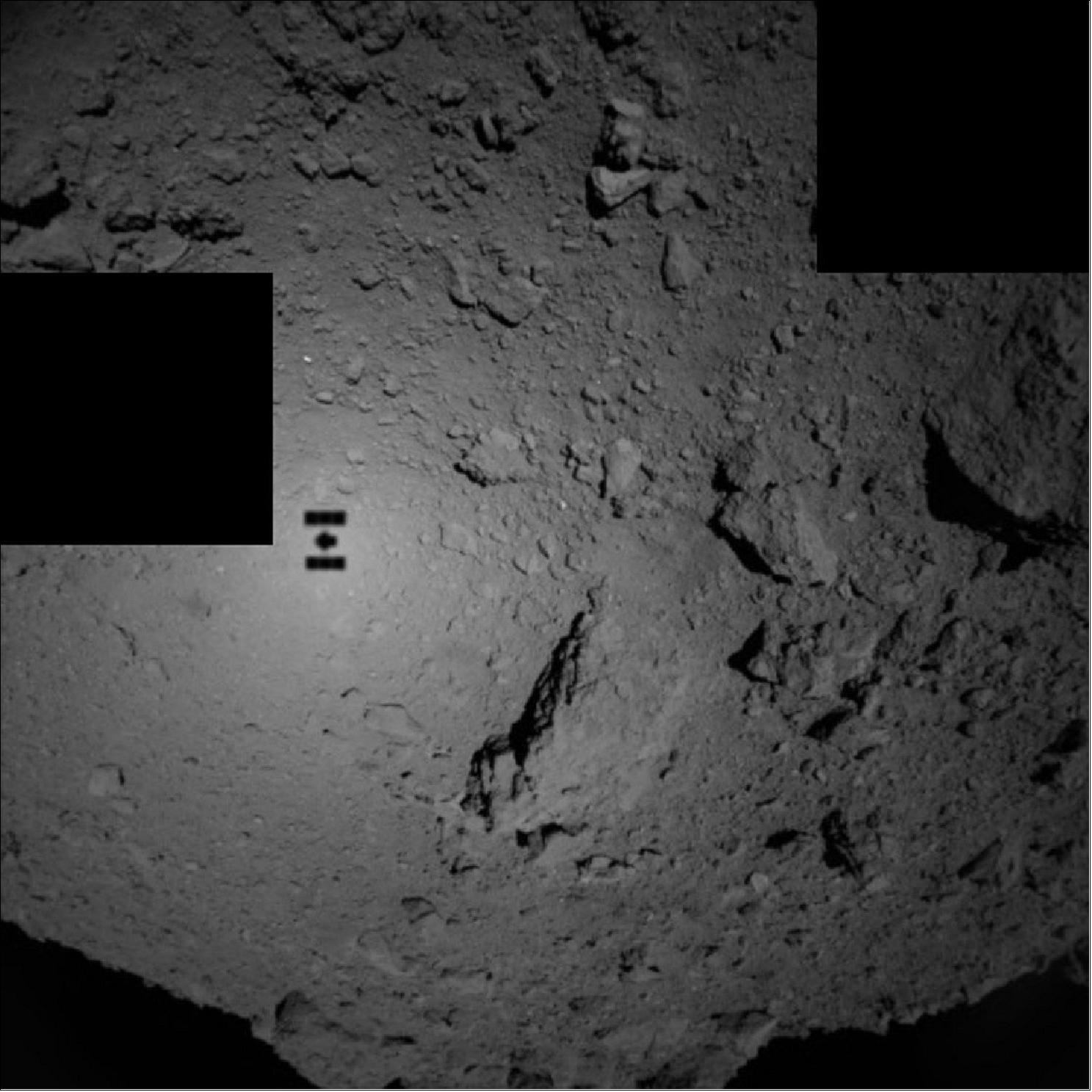

• May 8, 2020: High-resolution images and video were taken by the Japanese space agency's Hayabusa-2 spacecraft as it briefly landed to collect samples from Ryugu - a nearby asteroid that orbits mostly between Earth and Mars - allowing researchers to get an up-close look at its rocky surface, according to a new report. During the touchdown Hayabusa-2 obtained a sample of the asteroid, which it will bring back to Earth in December 2020. 30)

- The detailed new observations of Ryugu's surface during the touchdown operations help scientists understand the age and geologic history of the asteroid, suggesting that its surface color variations are likely due to rapid solar heating during a previous temporary orbital excursion near the Sun.

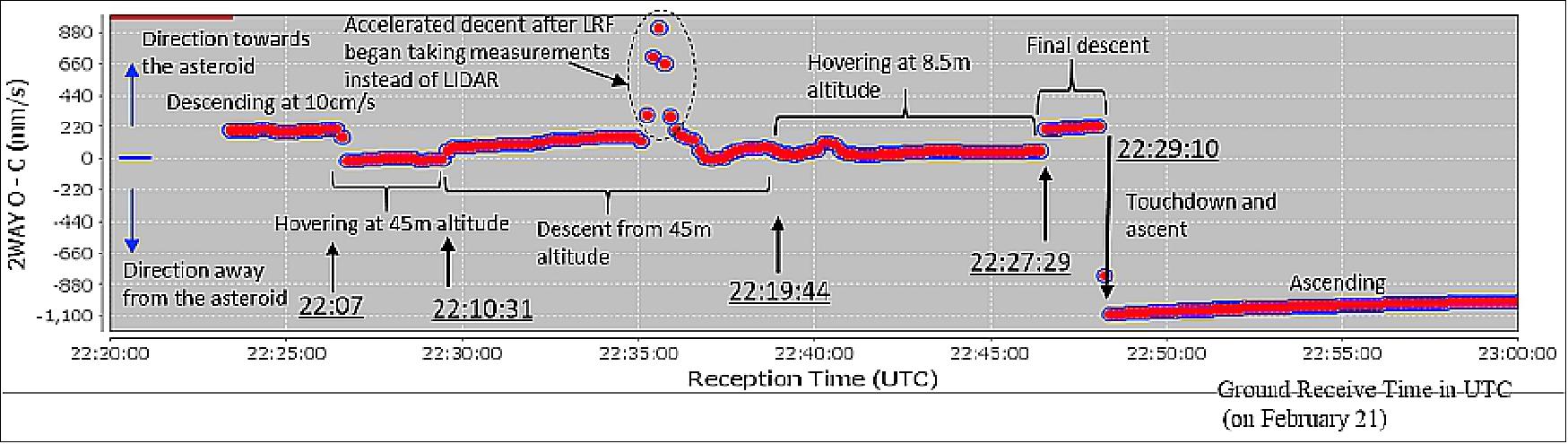

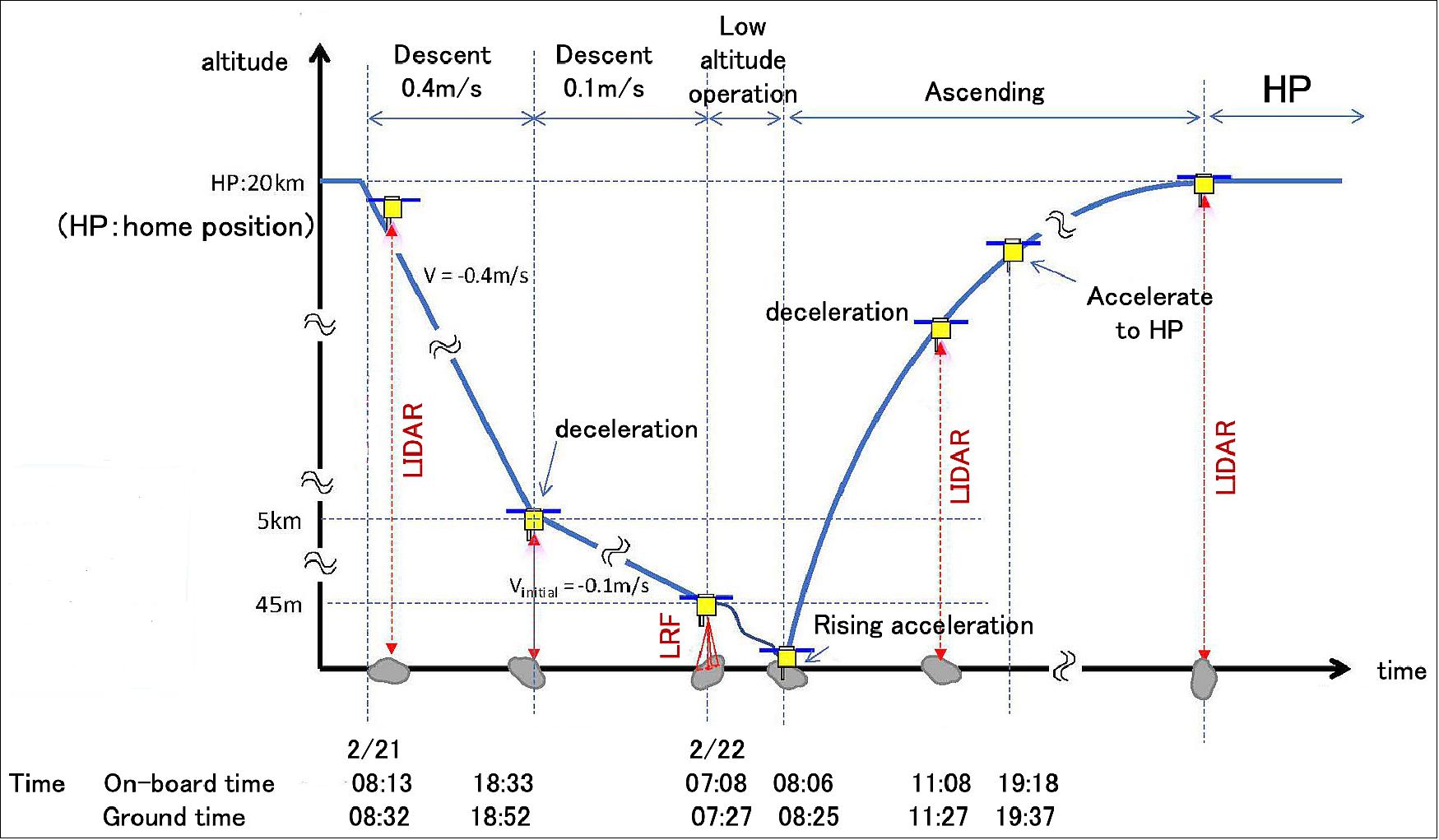

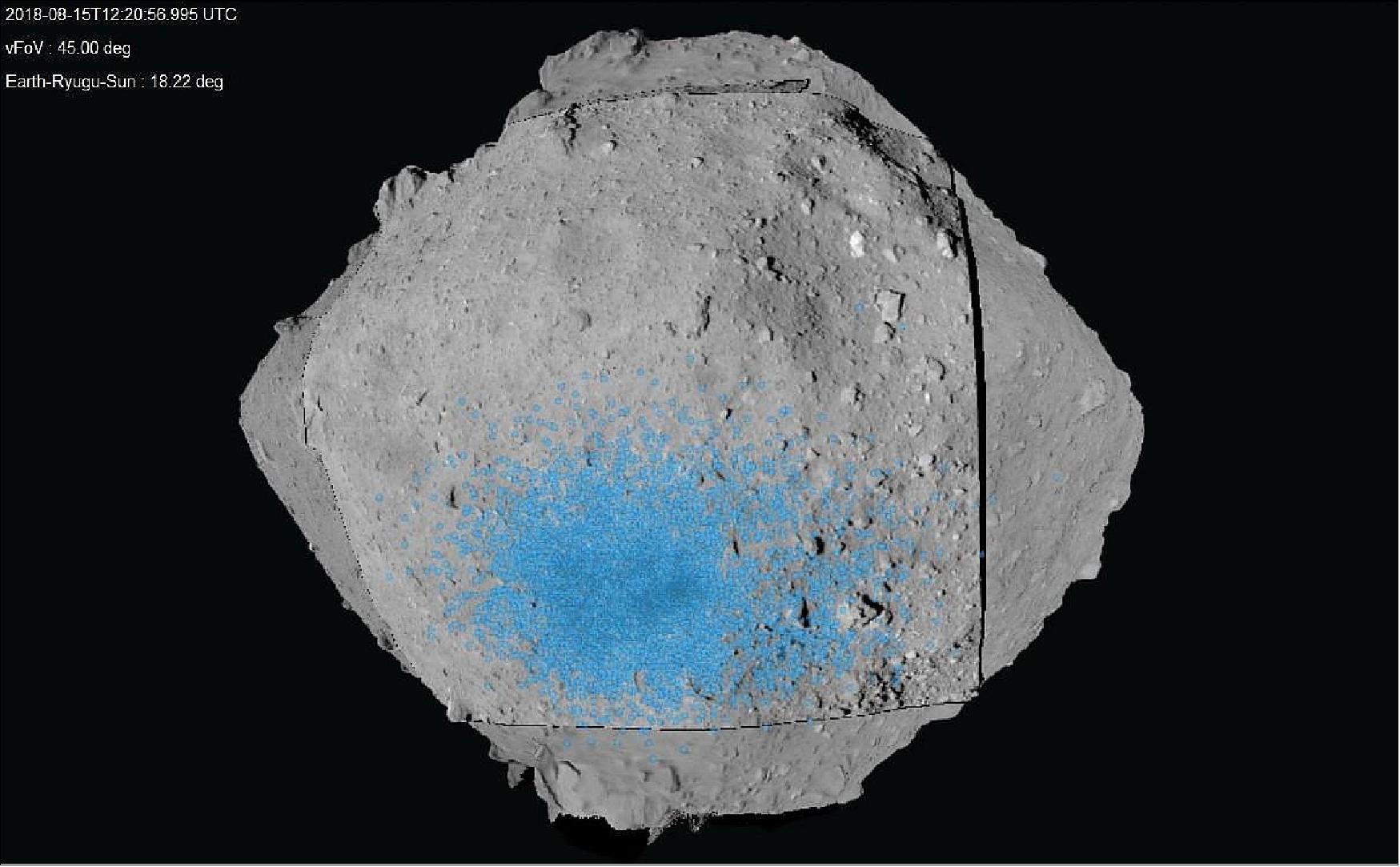

- On February 21, 2019, after months of orbital observations to select the target location, the Hayabusa-2 spacecraft descended to the surface of Ryugu to conduct its first sample collection, picking up surface material from the carbon-rich asteroid. Previous Hayabusa-2 observations have shown that Ryugu's surface is composed of two different types of material, one slightly redder and the other slightly bluer.

- The cause of this color variation, however, remained unknown. During Hayabusa-2's touchdown, onboard cameras captured high-resolution observations of the surface surrounding the landing site in exceptional detail - including the disturbances caused by the sampling operation. Tomokatsu Morota and colleagues used these images to investigate the geology and evolution of Ryugu's surface.

- Unexpectedly, Morota et al. observed that Hayabusa-2's thrusters disturbed a coating of dark, fine-grained material that appeared to correspond with the surface's redder materials. By relating these findings with the stratigraphy of the asteroid's craters, the authors conclude that surface reddening was caused by a short period of intense solar heating, which could be explained if Ryugu's orbit took a temporary turn towards the Sun. 31)

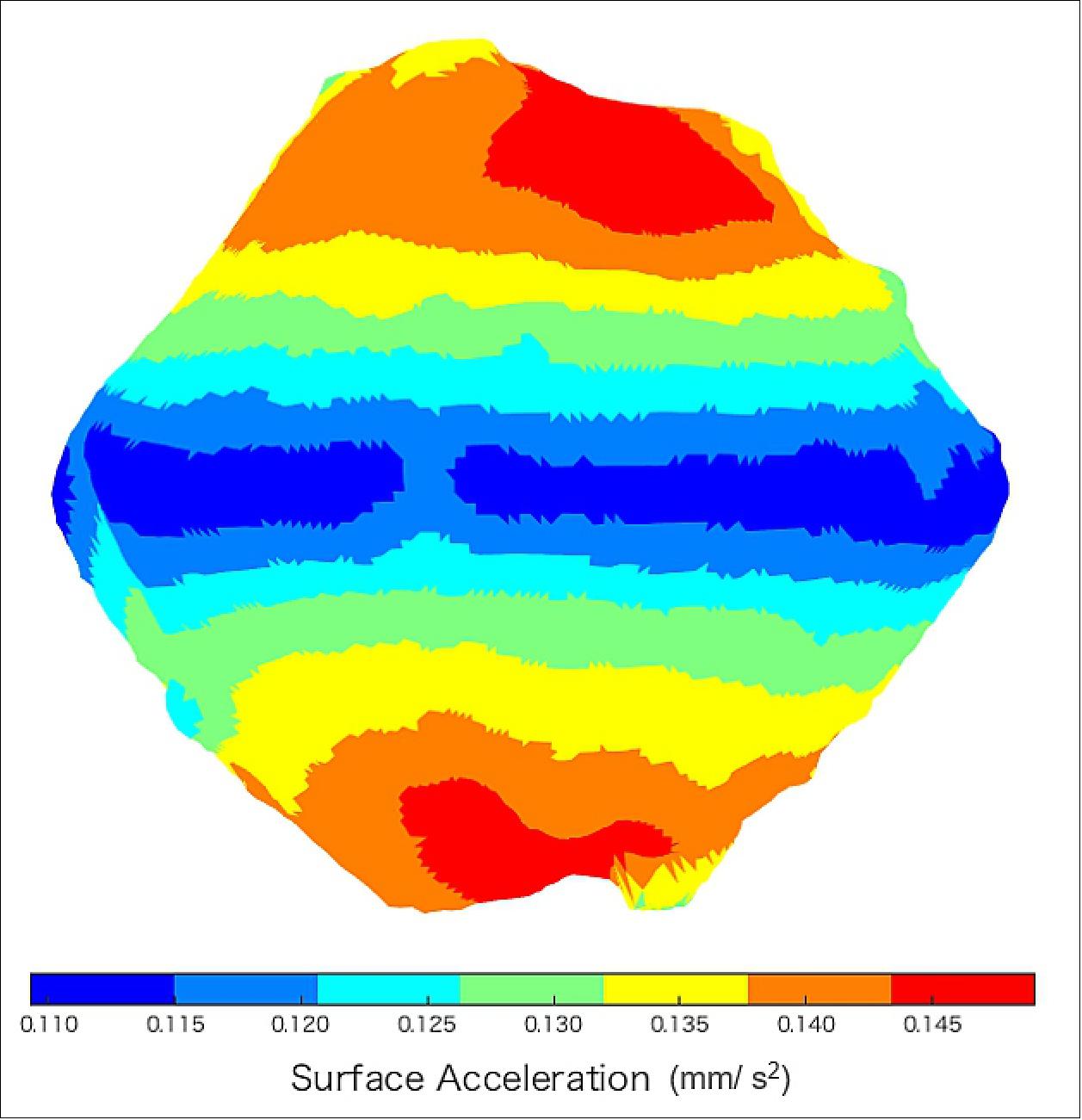

• March 16, 2020: Carbonaceous (C-type) asteroids are relics of the early Solar System that have preserved primitive materials since their formation approximately 4.6 billion years ago. They are probably analogues of carbonaceous chondrites and are essential for understanding planetary formation processes. However, their physical properties remain poorly known because carbonaceous chondrite meteoroids tend not to survive entry to Earth’s atmosphere. 32)

• March 16, 2020: The Solar System formed approximately 4.5 billion years ago. Numerous fragments that bear witness to this early era orbit the Sun as asteroids. Around three-quarters of these are carbon-rich C-type asteroids, such as 162173 Ryugu, which was the target of the Japanese Hayabusa2 mission in 2018 and 2019. The spacecraft is currently on its return flight to Earth. Numerous scientists, including planetary researchers from the German Aerospace Center (DLR), intensively studied this cosmic 'rubble pile', which is almost 1 km in diameter. Infrared images acquired by Hayabusa-2 have now been published in the scientific journal Nature. They show that the asteroid consists almost entirely of highly porous material. Ryugu was formed largely from fragments of a parent body that was shattered by impacts. The high porosity and the associated low mechanical strength of the rock fragments that make up Ryugu ensure that such bodies break apart into numerous fragments upon entering Earth's atmosphere. For this reason, carbon-rich meteorites are very rarely found on Earth and the atmosphere tends to offer greater protection against them. 33)

Thermal Behavior

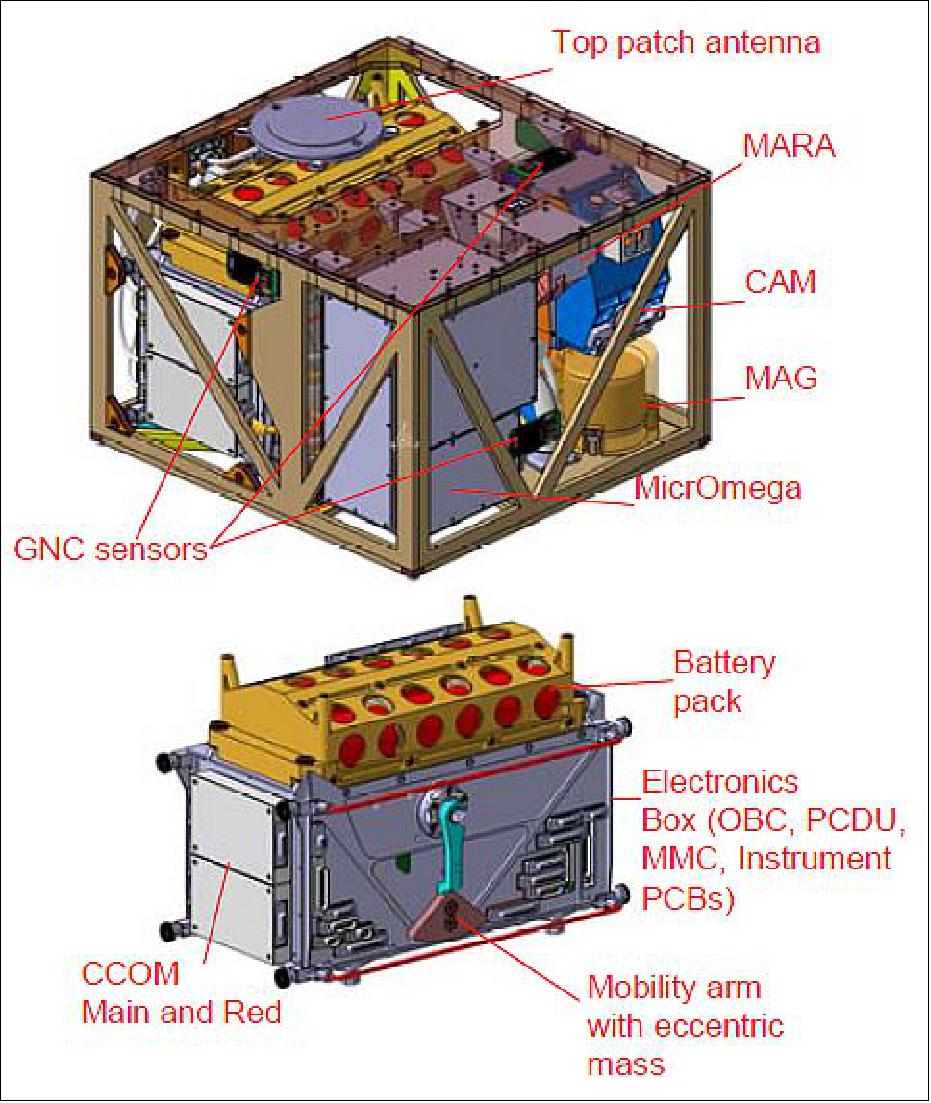

- This investigation of the global properties of Ryugu confirms and complements the findings of the landing environment on Ryugu obtained by the German-French 'Mobile Asteroid Surface SCOuT' (MASCOT) lander during the Hayabusa-2 mission. "Fragile, highly porous asteroids like Ryugu are probably the link in the evolution of cosmic dust into massive celestial bodies," says Matthias Grott from the DLR Institute of Planetary Research, who is one of the authors of the current Nature publication. "This closes a gap in our understanding of planetary formation, as we have hardly ever been able to detect such material in meteorites found on Earth."

- In autumn 2018, the scientists working with first author Tatsuaki Okada of the Japanese space agency JAXA analyzed the asteroid’s surface temperature in several series of measurements performed with the Thermal Infrared Imager (TIR) on board Hayabusa-2. These measurements were made in the 8 to 12 µm wavelength range during day and night cycles. In the process, they discovered that, with very few exceptions, the surface heats up very quickly when exposed to sunlight. "The rapid warming after sunrise, from approximately minus 43 degrees Celsius to plus 27 degrees Celsius suggests that the constituent pieces of the asteroid have both low density and high porosity," explains Grott. About one percent of the boulders on the surface were colder and more similar to the meteorites found on Earth. "These could be more massive fragments from the interior of an original parent body, or they may have come from other sources and fallen onto Ryugu," adds Jörn Helbert from the DLR Institute of Planetary Research, who is also an author of the current Nature publication.

From Planetesimals to Planets

- The fragile porous structure of C-type asteroids might be similar to that of planetesimals, which formed in the primordial solar nebula and accreted during numerous collisions to form planets. Most of the collapsing mass of the pre-solar cloud of gas and dust accumulated in the young Sun. When a critical mass was reached, the heat-generating process of nuclear fusion began in its core.

- The remaining dust, ice and gas accumulated in a rotating accretion disk around the newly formed star. Through the effects of gravity, the first planetary embryos or planetesimals were formed in this disc approximately 4.5 billion years ago. The planets and their moons formed from these planetesimals after a comparatively short period of perhaps only 10 million years. Many minor bodies – asteroids and comets – remained. These were unable to agglomerate to form additional planets due to gravitational disturbances, particularly those caused by Jupiter – by far the largest and most massive planet.

- However, the processes that took place during the early history of the Solar System are not yet fully understood. Many theories are based on models and have not yet been confirmed by observations, partly because traces from these early times are rare. "Research on the subject is therefore primarily dependent on extraterrestrial matter, which reaches Earth from the depths of the Solar System in the form of meteorites," explains Helbert. It contains components from the time when the Sun and planets were formed. "In addition, we need missions such as Hayabusa2 to visit the minor bodies that formed during the early stages of the Solar System in order to confirm, supplement or – with appropriate observations – refute the models."

A Rock Like Many on Ryugu

- Already in the summer of 2019, results from the MASCOT lander mission showed that its landing site on Ryugu was mainly populated by large, highly porous and fragile boulders. "The published results are a confirmation of the results from the studies by the DLR radiometer MARA on MASCOT," said Matthias Grott, the Principal Investigator for MARA. "It has now been shown that the rock analyzed by MARA is typical for the entire surface of the asteroid. This also confirms that fragments of the common C-type asteroids like Ryugu probably break up easily due to low internal strength when entering Earth’s atmosphere."

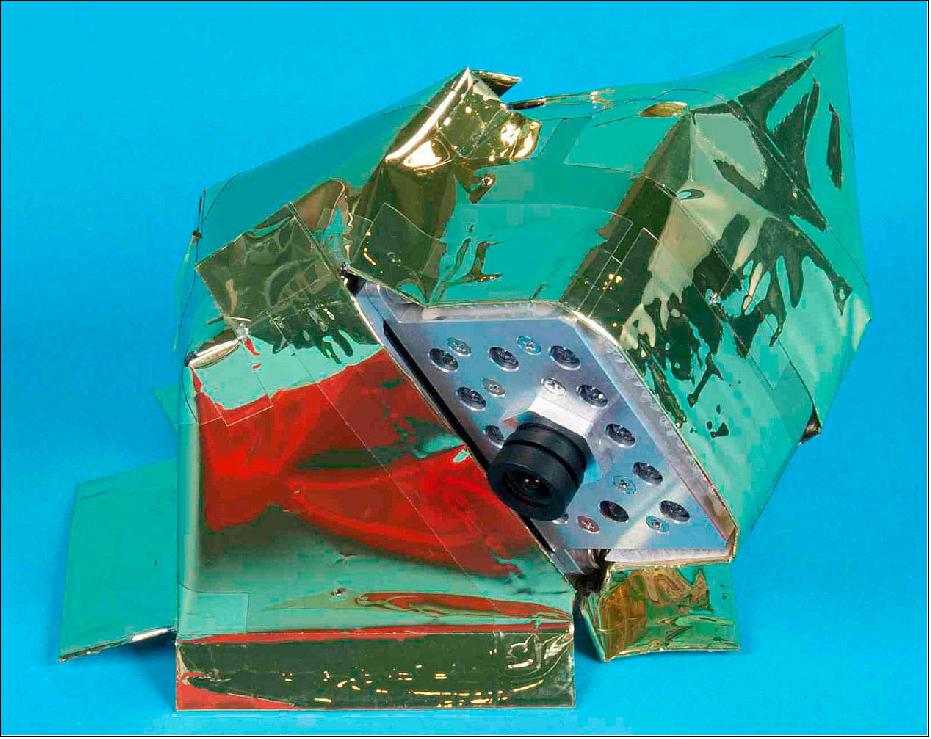

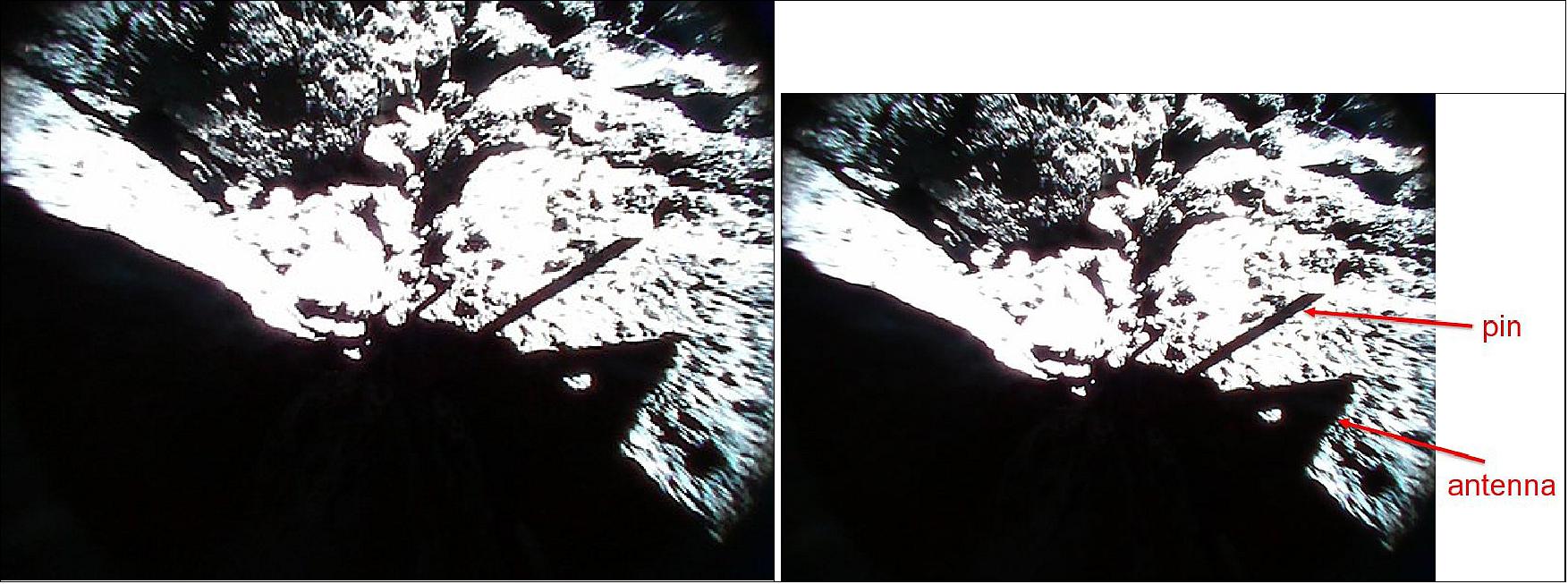

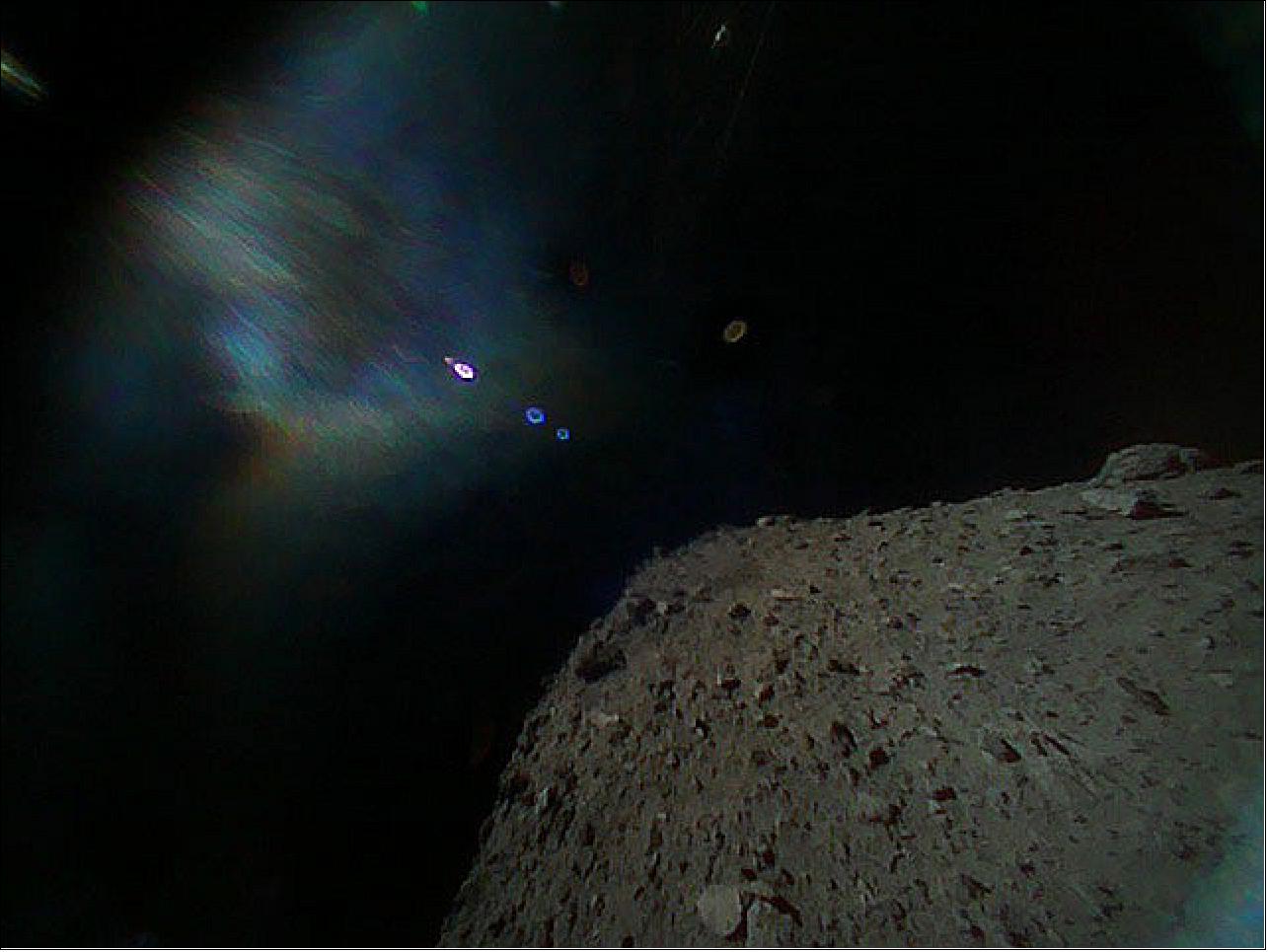

- On 3 October 2018, MASCOT landed on Ryugu in free fall at walking pace. Upon touchdown, it 'bounced' several meters further before the approximately 10-kilogram experiment package came to a halt. MASCOT moved on the surface with the help of a rotating swing arm. This made it possible to turn MASCOT on its 'right' side and even perform jumps on the asteroid’s surface due to Ryugu's low gravitational attraction. In total, MASCOT performed experiments on Ryugu for approximately 17 hours.

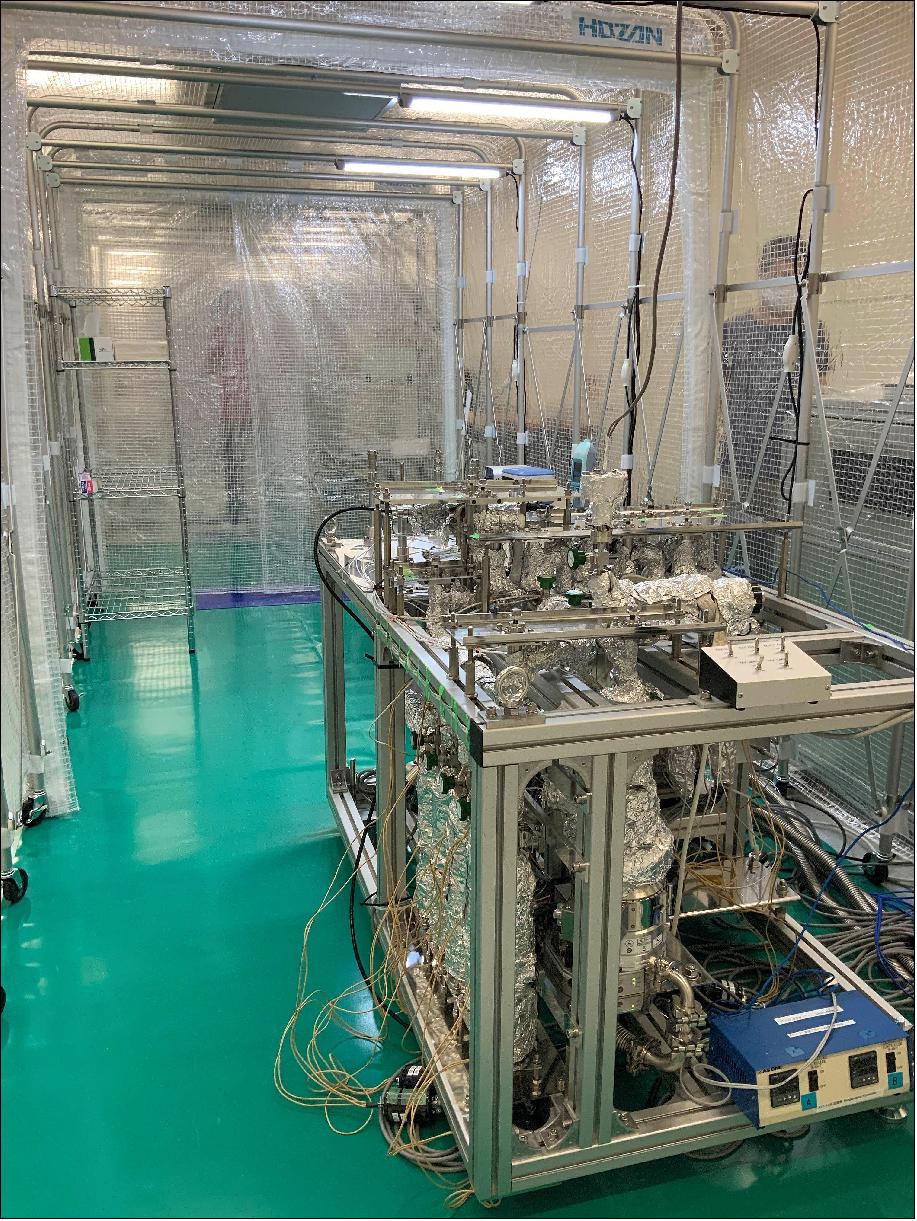

Samples From Asteroid Ryugu

- Hayabusa-2 mapped the asteroid from orbit at high resolution, and later acquired samples of the primordial body from two landing sites. These are currently sealed in a transport capsule and are traveling to Earth with the spacecraft. The capsule is scheduled to land in Australia at the end of 2020. So far, the researchers assume that Ryugu's material is chemically similar to that of chondritic meteorites, which are also found on Earth. Chondrules are small, millimeter-sized spheres of rock, which formed in the primordial solar nebula 4.5 billion years ago and are considered to be the building blocks of planetary formation. So far, however, scientists cannot rule out the possibility that they are made of carbon-rich material, such as that found on comet 67P/ Churyumov-Gerasimenko as part of ESA's Rosetta mission with the DLR-operated Philae lander. Analyses of the samples from Ryugu, some of which will be carried out at DLR, are eagerly awaited. "It is precisely for this task – and of course for future missions such as the Japanese 'Martian Moons exploration' (MMX) mission, in which extraterrestrial samples will be brought to Earth – that we at DLR's Institute of Planetary Research in Berlin began setting up the Sample Analysis Laboratory (SAL) last year," says Helbert. The MMX mission, in which DLR is participating, will fly to the Martian moons Phobos and Deimos in 2024 and bring samples from the asteroid-sized moons to Earth in 2029. A mobile German-French rover will also be part of the MMX mission.

Hayabusa-1

Some background of Hayabusa-1: This rather important result of the Hayabusa-1 mission of JAXA was inserted in the Hayabusa-2 file due to a lack of a Hayabusa-1 file on the eoPortal. The MUSES-C (Mu Space Engineering Satellite) mission; launch May 9, 2003) with the nickname ”Hayabusa”, was a deep space asteroid sample return mission of JAXA. - In Nov. 2005, the spacecraft performed five descents, among which two touch-down flights were included. Actually Hayabusa made three touch-downs and one long landing on the surface of asteroid Itokawa during those two flights.

- After overcoming multiple serious glitches, and a three-year delay in its round-trip journey of over 5 billion km (or 5 x 109 km), JAXA's Hayabusa sample return canister landed in South Australia (Woomera) on June 13, 2010. The canister separated from the spacecraft about three hours before reaching Earth, and returned to Earth via parachute. The canister has been recovered by JAXA engineers, and will be taken to Japan where scientists will open it to find out if there is anything inside. 34)

- On Nov. 16, 2010, JAXA confirmed that the tiny particles inside the Hayabusa spacecraft‘s sample return container are in fact from the asteroid Itokawa. 35) Based on the results of the scanning electron microscope (SEM) observations and analyses of samples that were collected with a special spatula from sample catcher compartment "A", about 1,500 grains were identified as rocky particles, and most of them were judged to be of extraterrestrial origin, and definitely from Asteroid Itokawa. Their size is mostly less than 10 µm, and handling these grains requires very special skills and techniques. - These are the first samples from an asteroid ever returned to Earth.

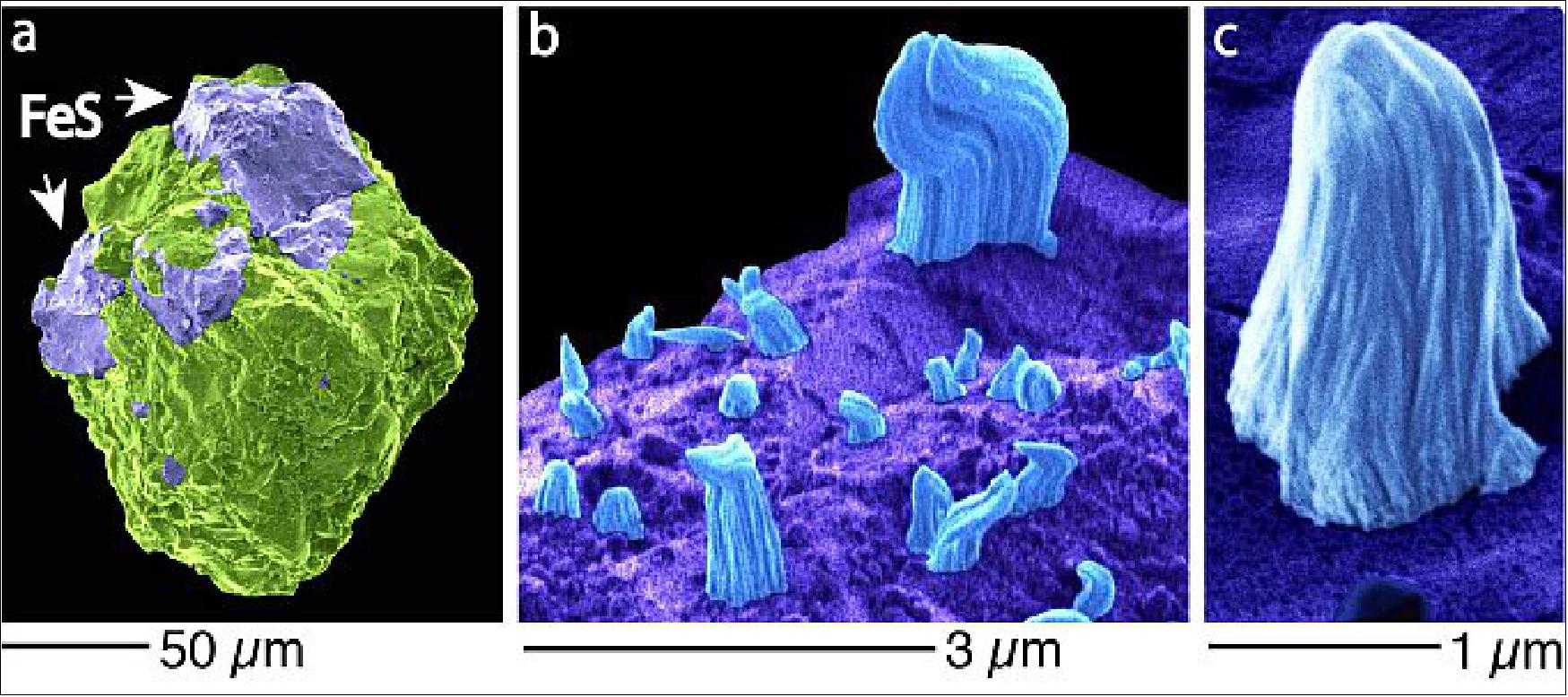

• February 28, 2020: Mineralogists from FSU (Friedrich Schiller Universität) Jena, Germany, and Japan discover a previously unknown phenomenon in soil samples from the asteroid ‘Itokawa’: the surface of the celestial body is covered with tiny hair-shaped iron crystals. The team provides an explanation of how these were formed, and why asteroids can be unusually low in sulphur compounds, in the current issue of ‘Nature Communications’. 36) 37)

Itokawa would normally be a fairly average near-Earth asteroid - a rocky mass measuring only a few hundred meters in diameter, which orbits the sun amid countless other celestial bodies and repeatedly crosses the orbit of the Earth. But there is one fact that sets Itokawa apart: in 2005 it became a visit from Earth. The Japanese space agency JAXA sent the Hayabusa probe to Itokawa, which collected soil samples and brought them safely back to Earth — for the first time in the history of space travel. This valuable cargo arrived in 2010 and since then, the samples have been the subject of intensive research.

A team from Japan and Jena has now succeeded in coaxing a previously undiscovered secret from some of these tiny sample particles: the surface of the dust grains is covered with tiny wafer-thin crystals of iron. This observation surprised Prof. Falko Langenhorst and Dr Dennis Harries of Friedrich Schiller University in Jena. After all, over the last 10 years, research teams all over the world have exhaustively studied the structure and chemical composition of the dust particles from Itokawa, and no one had noticed the iron ‘whiskers’. It was only when Japanese researcher Dr Toru Matsumoto, who is spending a year as a visiting scientist with the Analytical Mineralogy group at the Institute of Geosciences in Jena, examined the particles with a transmission electron microscope that he was able to locate the crystals using high-resolution images.

Solar Wind Weathers Celestial Bodies

This discovery is exciting not only because the tiny iron ‘whiskers’ - which have since been shown on other particles from the asteroid as well - had previously been missed. Of particular interest is how they were formed. "These structures are the consequence of cosmic influences on the surface of the asteroid," explains Falko Langenhorst. In addition to rocks, high-energy particles from the solar wind also strike the asteroid’s surface, thus weathering it. An important constituent of the asteroid is the mineral troilite, in which iron and sulphur are bound. "As a result of space weathering, the iron is released from the troilite and deposited on the surface in the form of the needles that have now been discovered," says the mineralogist Langenhorst. The sulphur from the iron sulphide then evaporates into the surrounding vacuum in the form of gaseous sulphur compounds.

From the size and number of the ice crystals detected, the researchers can also estimate how quickly the asteroid loses sulphur. "The process is incredibly fast from a cosmic perspective," explains Toru Matsumoto. The crystals he analyzed are up to two-and-a-half micrometers long, which is around one-fiftieth of the thickness of a human hair. "The tiny whiskers have already reached these sizes after around 1,000 years," adds the researcher from Kyushu University in Fukuoka. Over the long term, the analysis of the ice crystals can be used to gain a better understanding of weathering processes on other celestial bodies as well, and to determine their age.

To this end, the researchers already have specific asteroids in their sights. NASA’s OSIRIS-REx probe is currently preparing to take samples from asteroid Bennu, while JAXA’s Hayabusa2 is already on its way back to Earth. The Japanese probe visited the Ryugu asteroid last year and, as with Itokawa, it collected dust particles. The samples should land on Earth at the end of 2020 and the international team of Jena mineralogists and Toru Matsumoto are awaiting them with anticipation

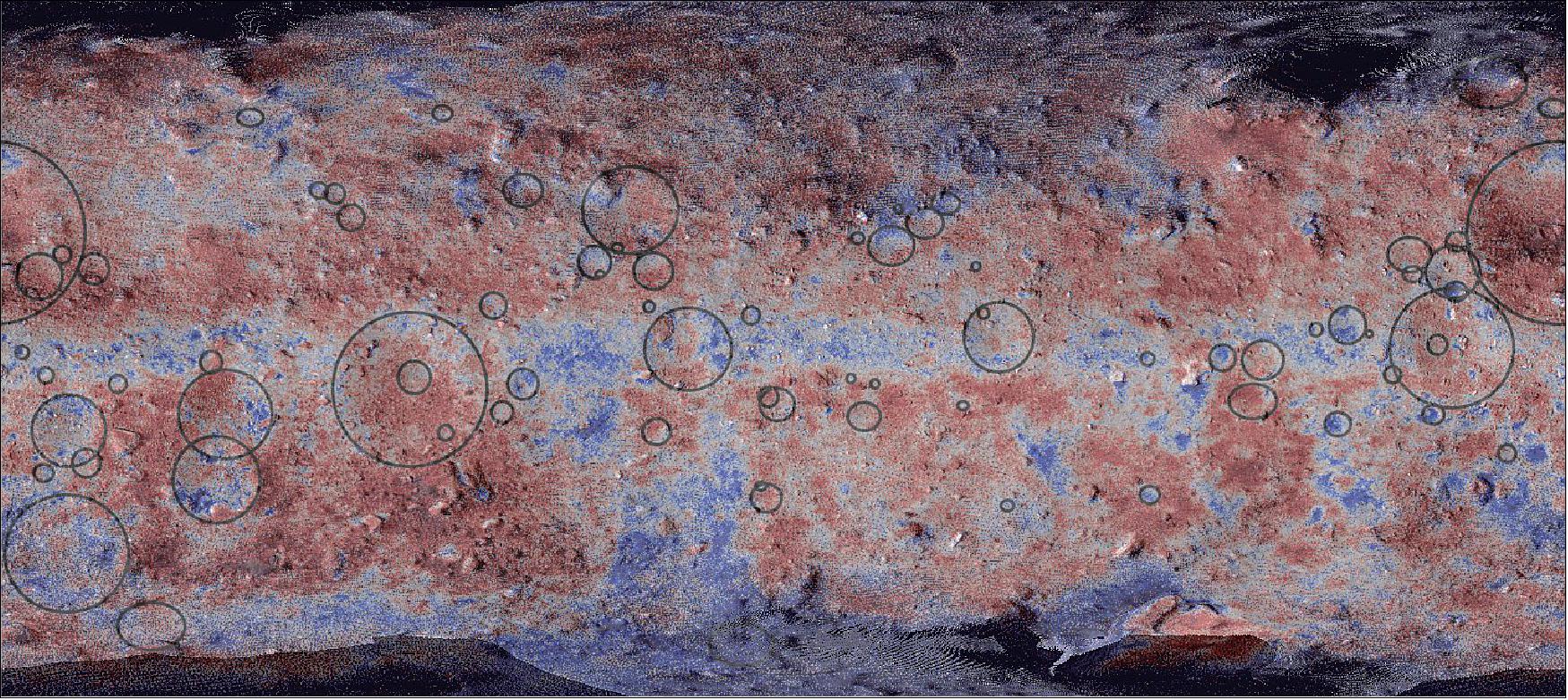

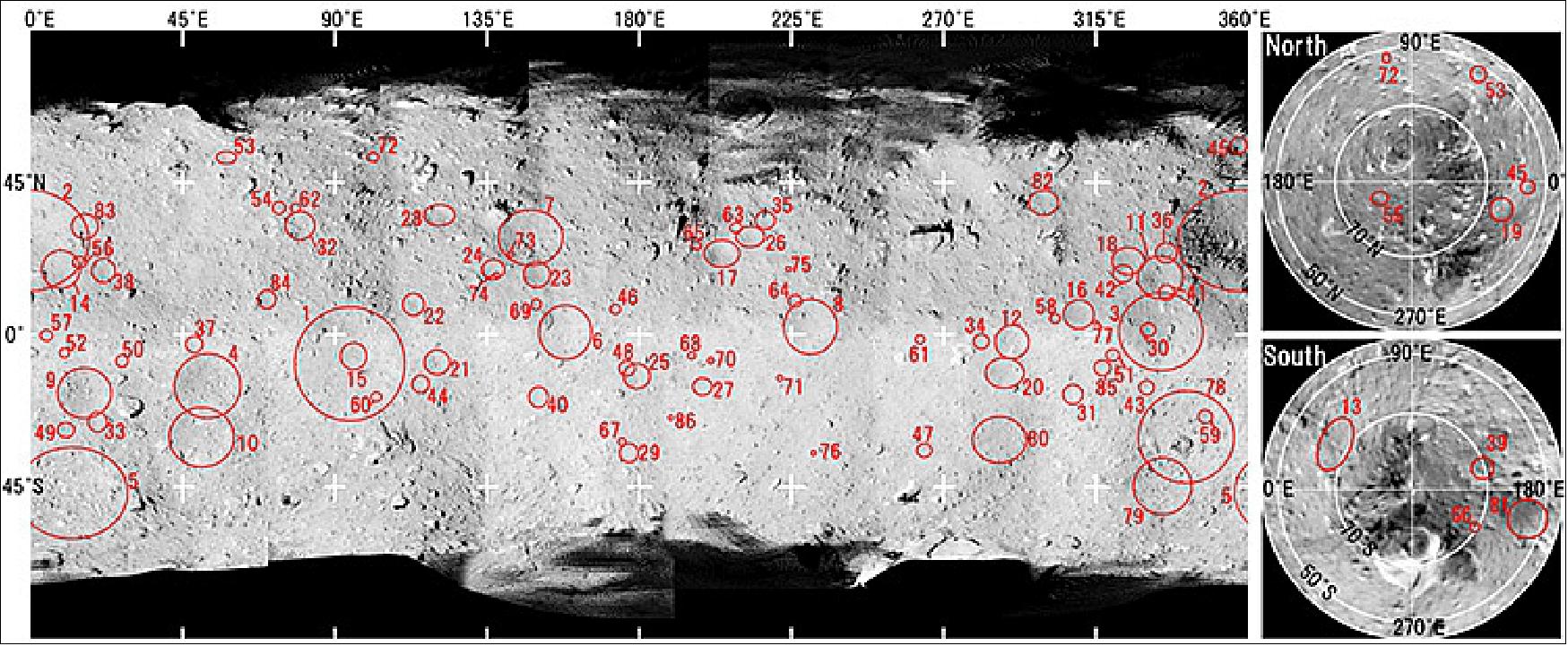

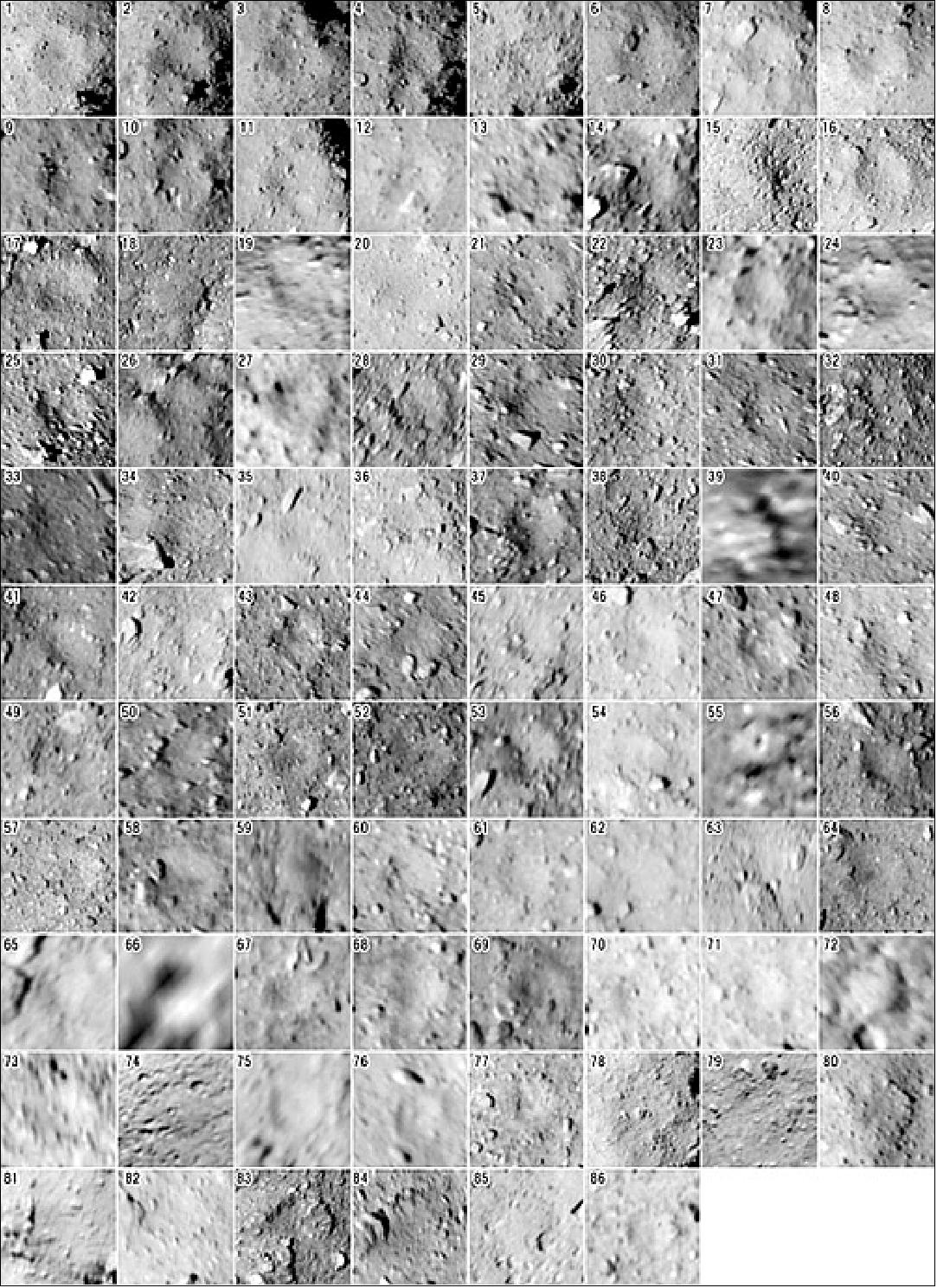

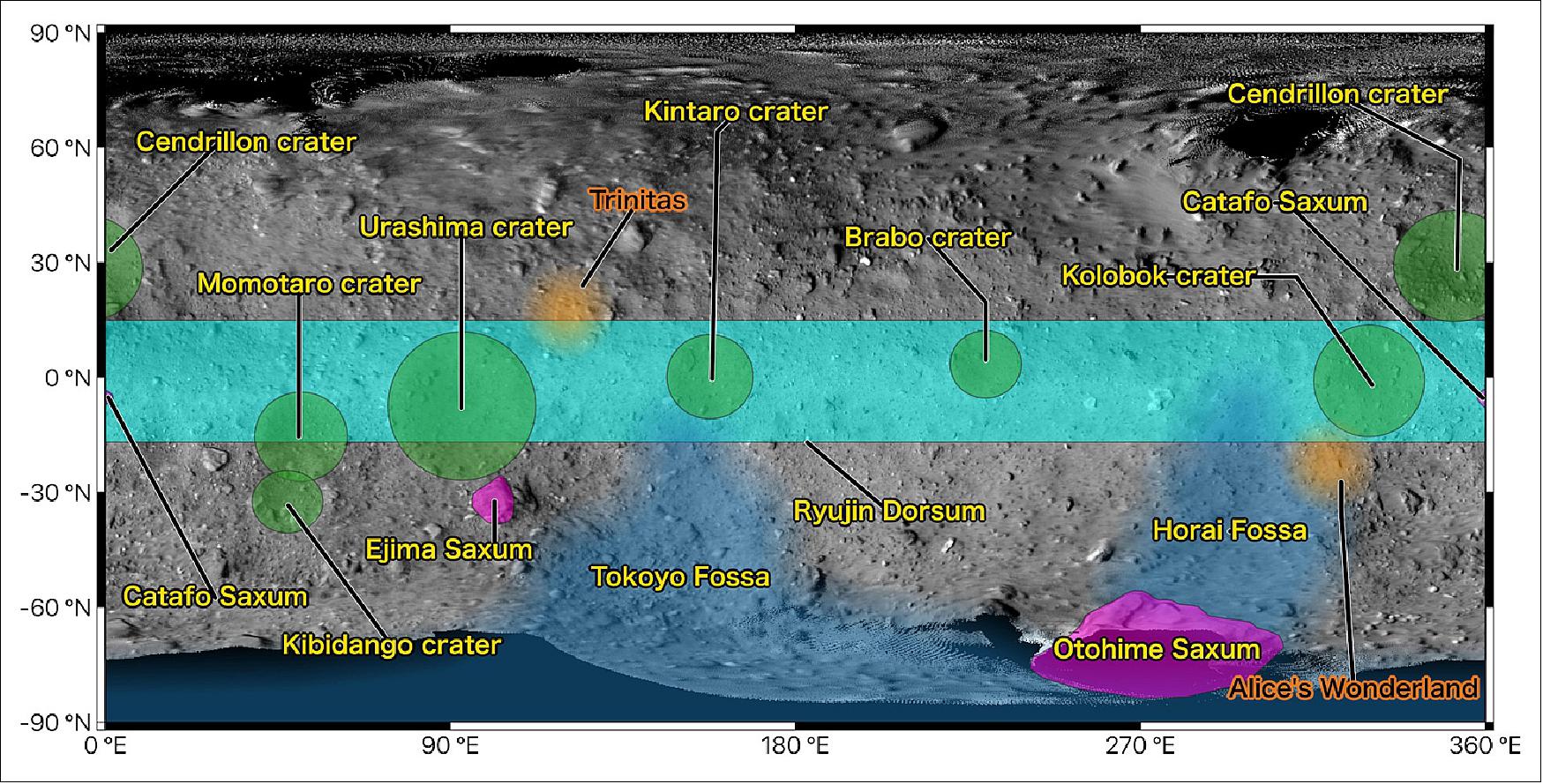

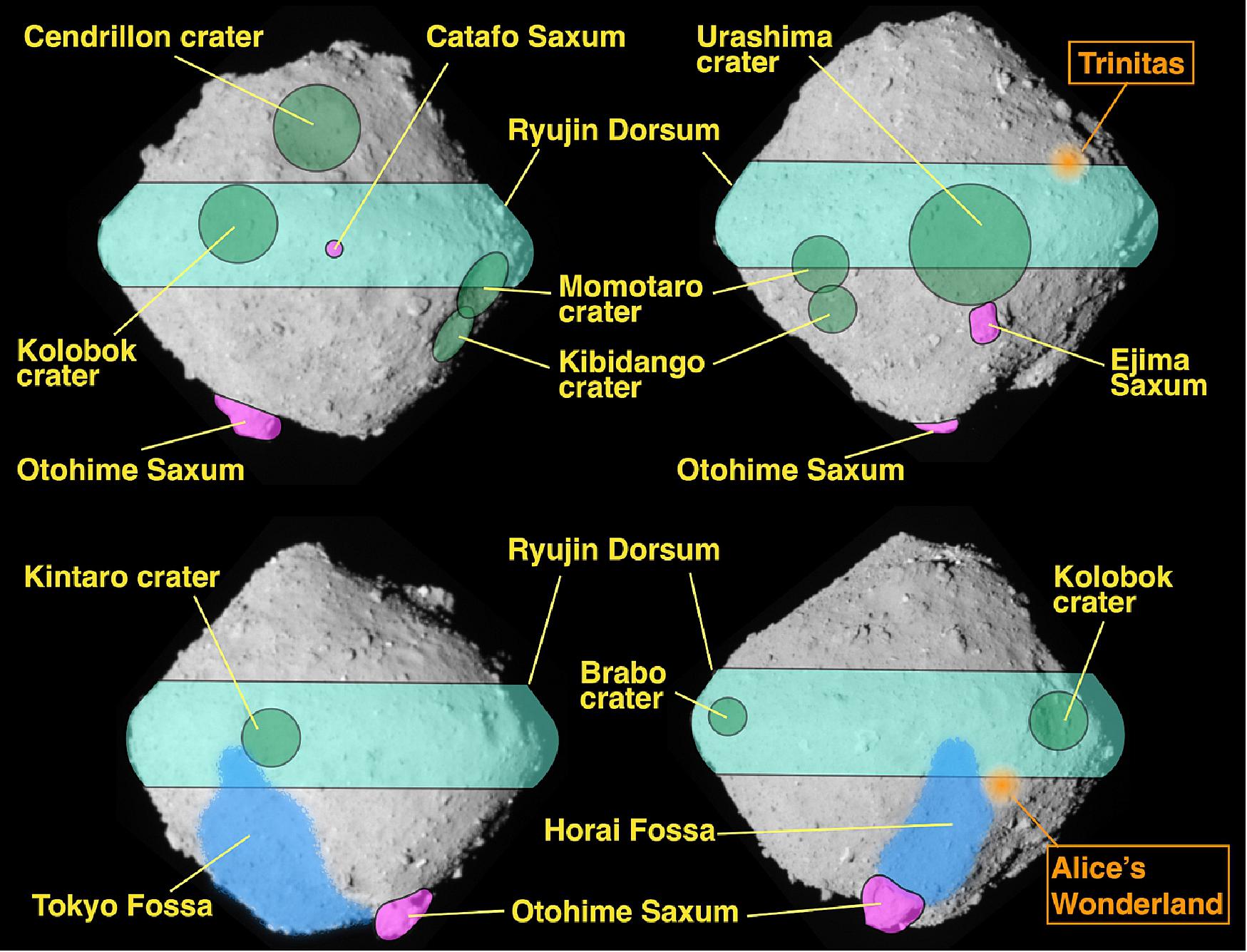

• November 27, 2019: Analysis of the impact craters on Ryugu using the spacecraft Hayabusa 2's remote sensing image data has illuminated the geological history of the Near-Earth asteroid. 38)

- A research group led by Assistant Professor Naoyuki Hirata of the Department of Planetology at Kobe University's Graduate School of Science revealed 77 craters on Ryugu. Through analyzing the location patterns and characteristics of the craters, they determined that the asteroid's eastern and western hemispheres were formed at different periods of time.

- It is hoped that the collected data can be used as a basis for future asteroid research and analysis. These results were first published in the American Scientific Journal 'Icarus' on November 5 2019.

- JAXA's Hayabusa-2 has been used to carry out various missions to increase our understanding of the spinning top-shaped, Near-Earth asteroid Ryugu. Since arriving in June 2018, the unmanned spacecraft has taken samples and a great number of images of the asteroid. It is hoped that these can reveal more about Ryugu’s formation and history.

- This research group focused on using the image data to determine the number and location of impact craters on the asteroid. Impact craters are formed when a smaller asteroid or a comet hits the surface of the asteroid. Analyzing the spatial distribution and the number of impact craters can reveal the frequency of collisions and aid researchers in determining the age of different surface areas.

Research Methodology

- First of all, the image data from Hayabusa-2 was analyzed. Hayabusa 2 has many different types of camera including Optical Navigation Cameras (ONC). The ONC team has been able to take around 5000 images of Ryugu, which have revealed many surface features- including impact craters. For this study, image data obtained from the ‘ONC-T’ camera between July 2018 and February 2019 was utilized. The research group had to determine which of these images showed craters. 340 images were used for crater counting, with stereopair images making it easier to identify the craters. A global image mosaic map was constructed from the ONC images and rendered onto the computer model of Ryugu’s shape. Small Body Mapping Tool software was then used to measure the size, latitude and longitude of the craters. A LiDAR (Light Detection and Ranging pulsed laser) was also utilized to determine the overall size of Ryugu.

- The depressions identified on Ryugu were divided into four categories- depending on how evident their circular appearance was. Category I to III depressions were classified as distinct craters. Category IV depressions only had quasi-circular features, therefore it was hard to determine whether they were craters or not. Many craters were filled with boulders or lacked a distinct shape. Depressions that were too vague to determine were left out of the results.

Research Results

- The research team were able to identify all impact craters over 10 to 20m in diameter on Ryugu’s entire surface- a total of 77 craters. Furthermore, a pattern was discovered in their distribution. The section of the eastern hemisphere near the meridian was found to have the most craters. This is the area near the large crater named Cendrillon - which is one of Ryugu’s biggest. In contrast, there are hardly any craters in the western hemisphere- suggesting that this part of the asteroid was formed later. The analysis also revealed that there are more craters at lower latitudes than at higher latitudes on Ryugu. In other words, there are very few craters in Ryugu’s polar regions.

- The equatorial ridge in the eastern hemisphere was determined to be a fossil structure. When asteroids like Ryugu rotate at high speeds, this can alter their shape. It is thought that this ridge formed in the distant past during a period when it only took Ryugu 3 hours to rotate. As the eastern hemisphere and western hemisphere were formed at different periods of the asteroid’s history- this suggests that there have been at least two instances where Ryugu’s rotational speed has increased.

• November 13, 2019: JAXA confirmed Hayabusa-2, JAXA's asteroid explorer, left the target asteroid Ryugu. 40)

- On November 13, 2019, JAXA operated the Hayabusa-2 chemical propulsion thrusters for the spacecraft's orbit control. The confirmation of the Hayabusa-2 departure made at 10:05 a.m. [JST (Japan Standard Time), 01:05 GMT] was based on the following data analyses:

a) The thruster operation of Hayabusa-2 occurred nominally

b) The velocity leaving from Ryugu is approximately 9.2 cm/s

c) The status of Hayabusa2 is nominal.

- The project is planning to conduct performance tests of onboard instruments, including the electric propulsion system, for the return to Earth. According to JAXA, the probe is expected to drop off its precious samples some time in late 2020.

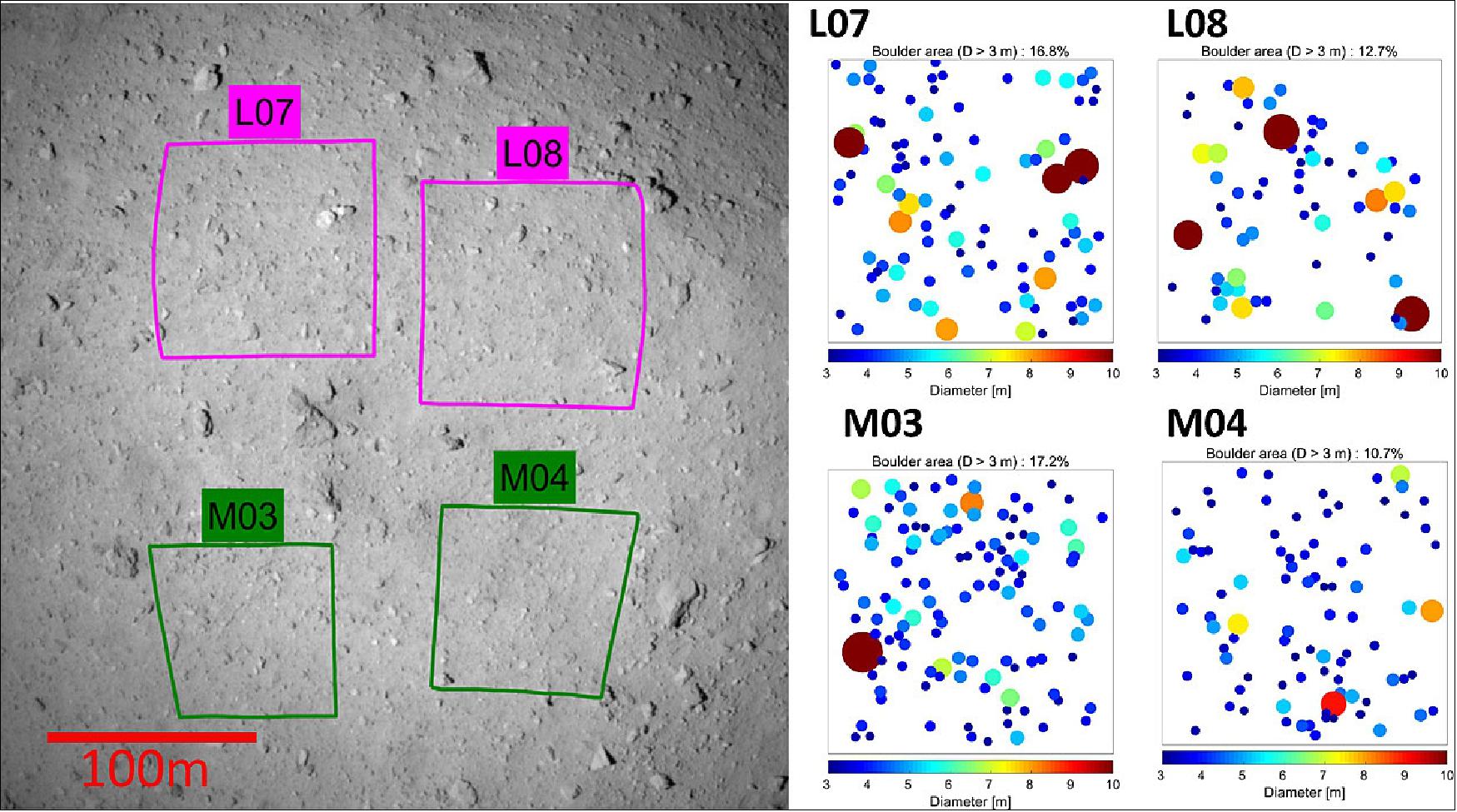

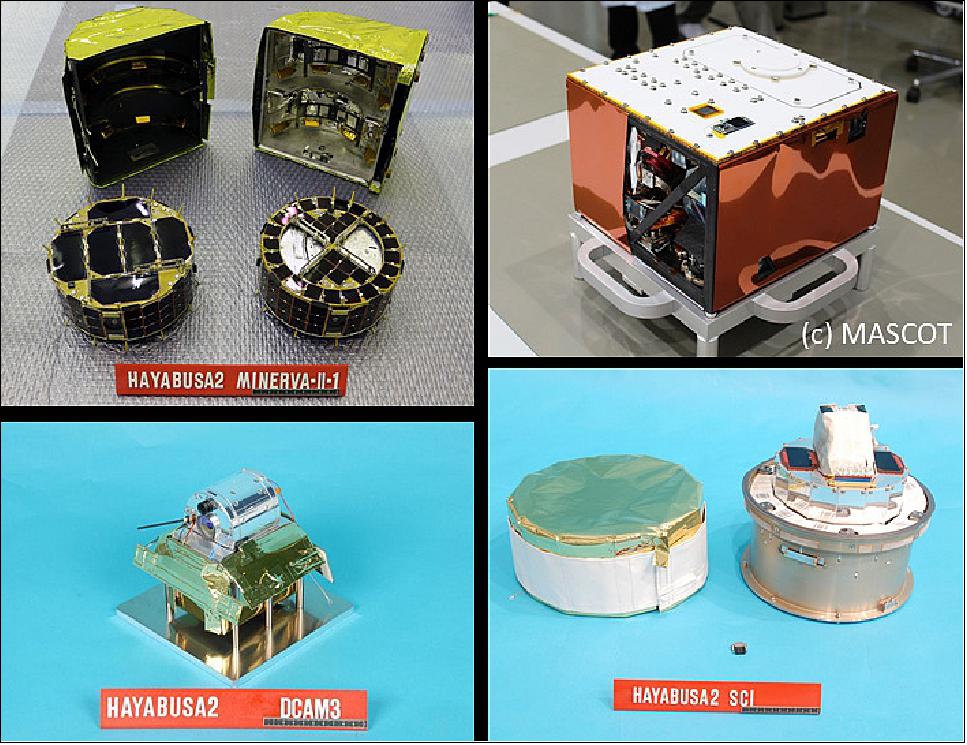

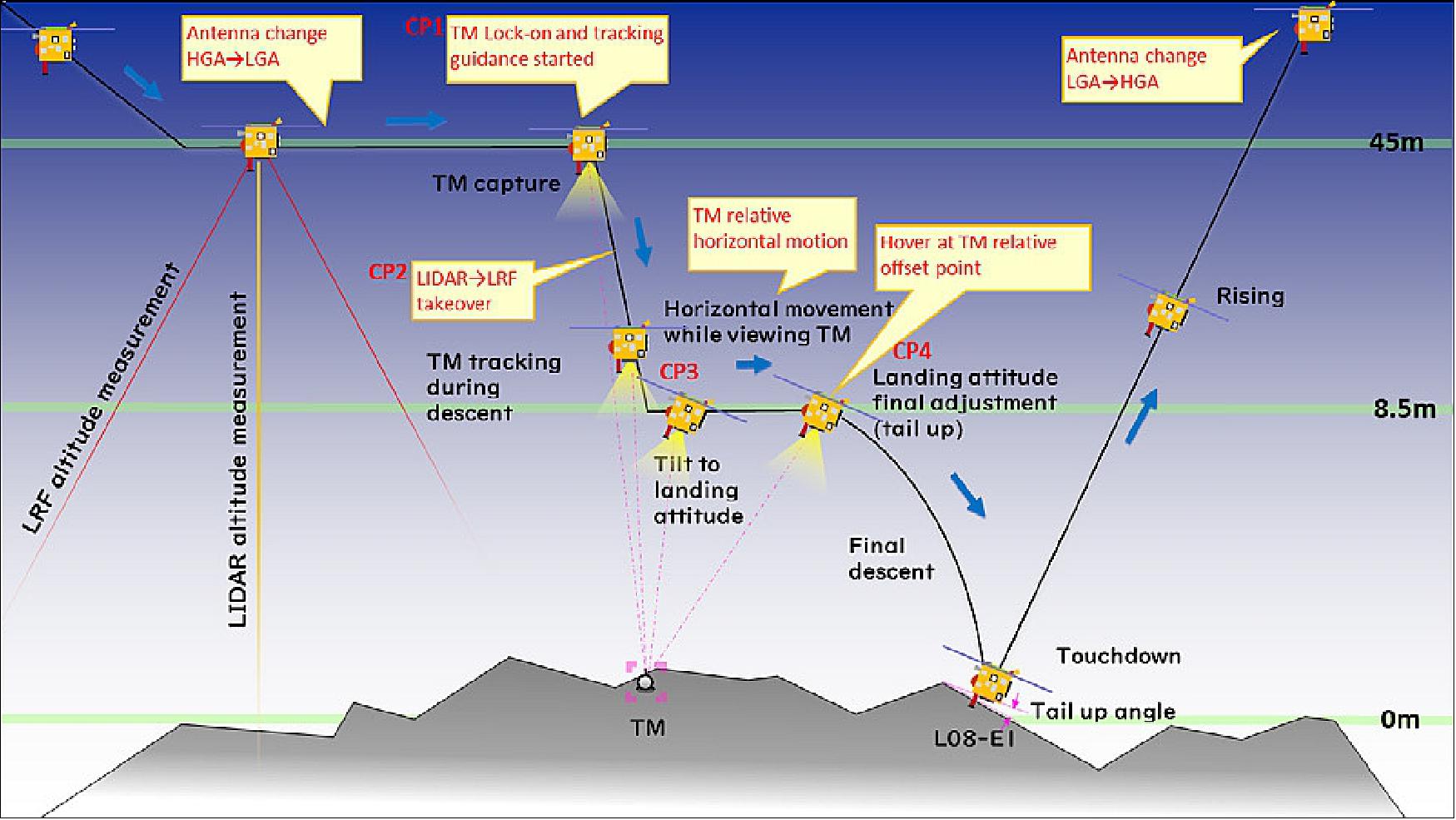

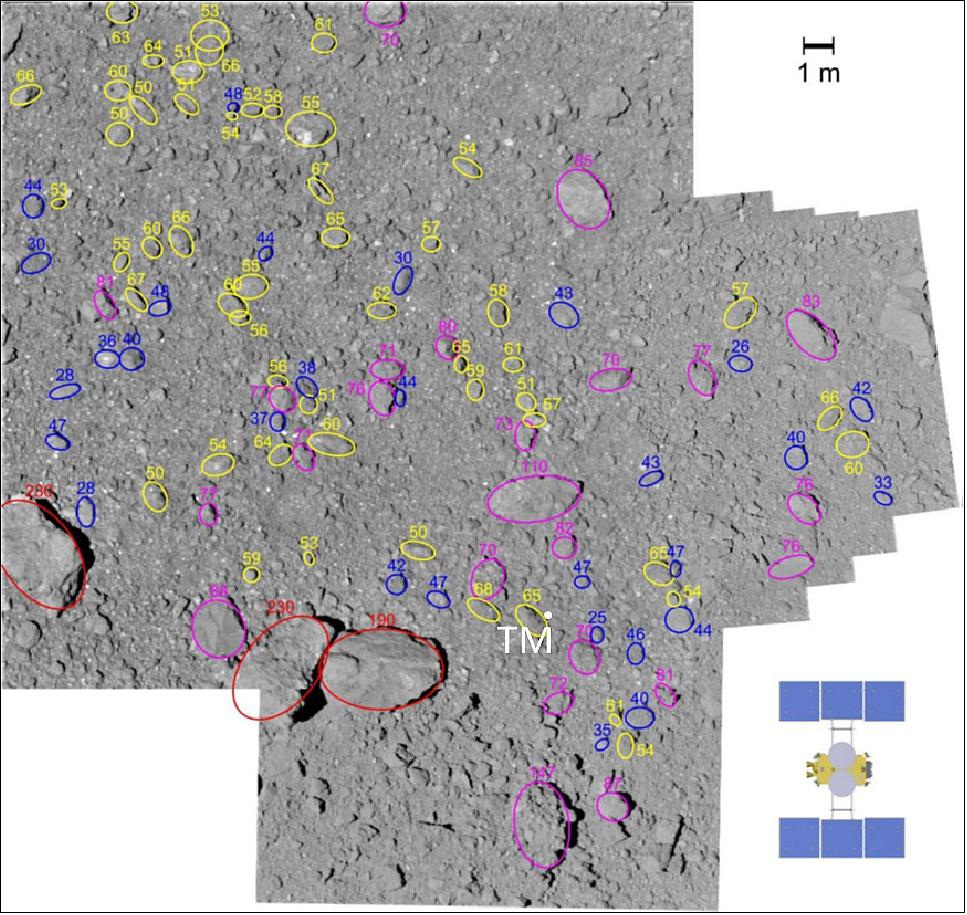

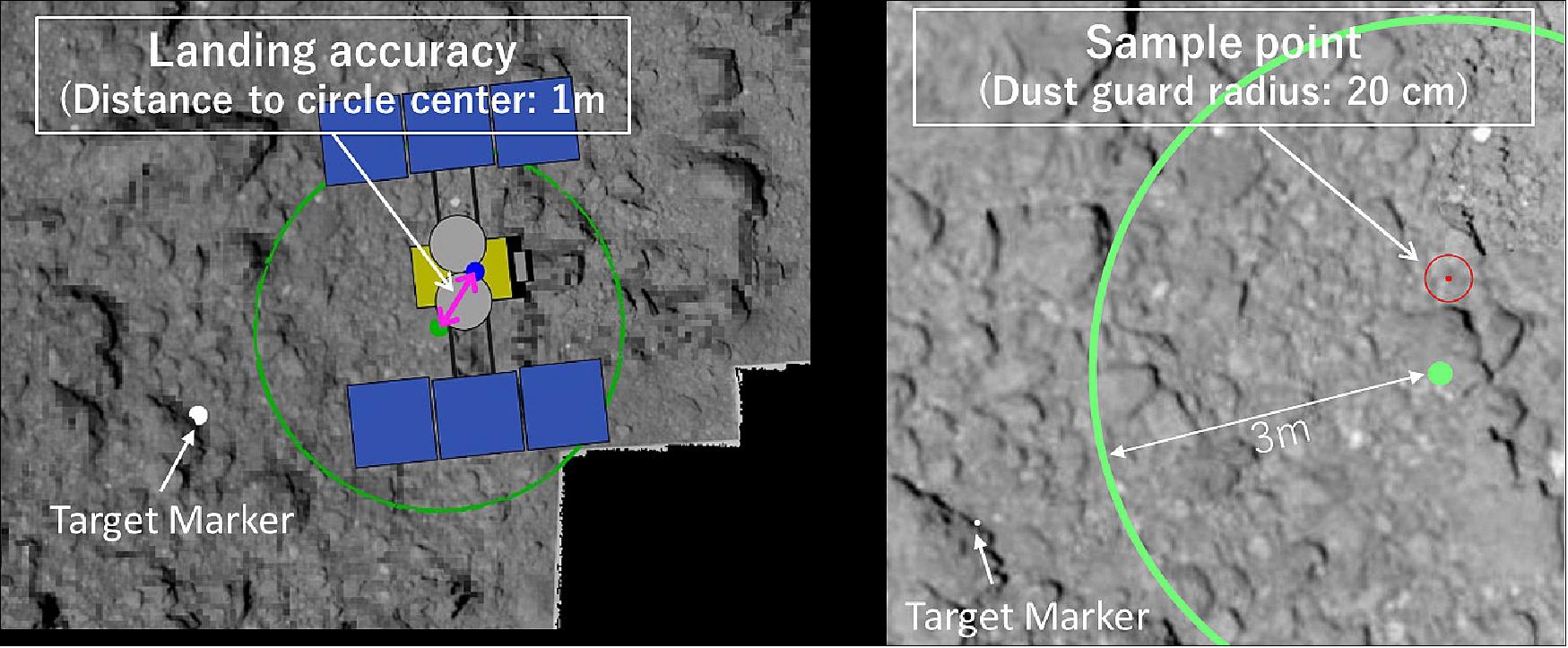

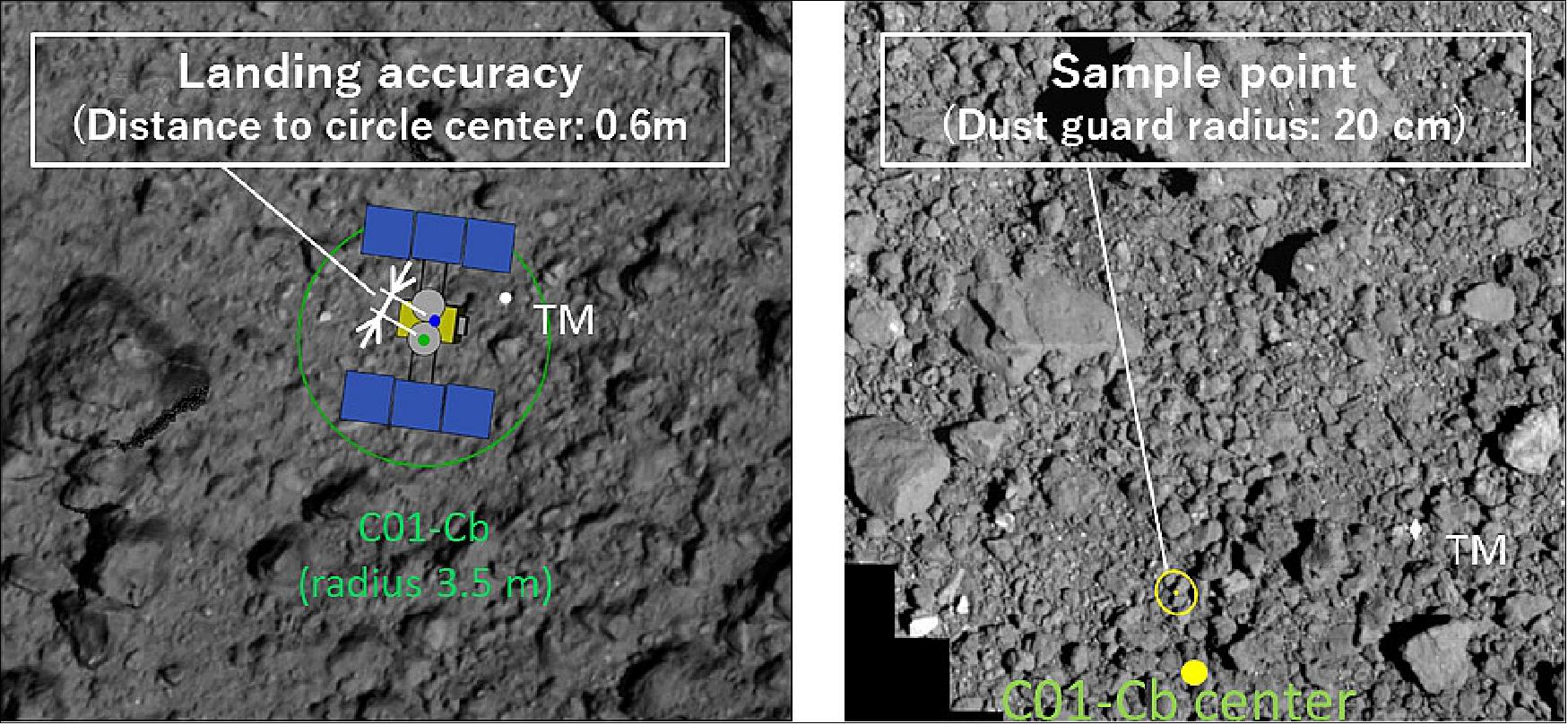

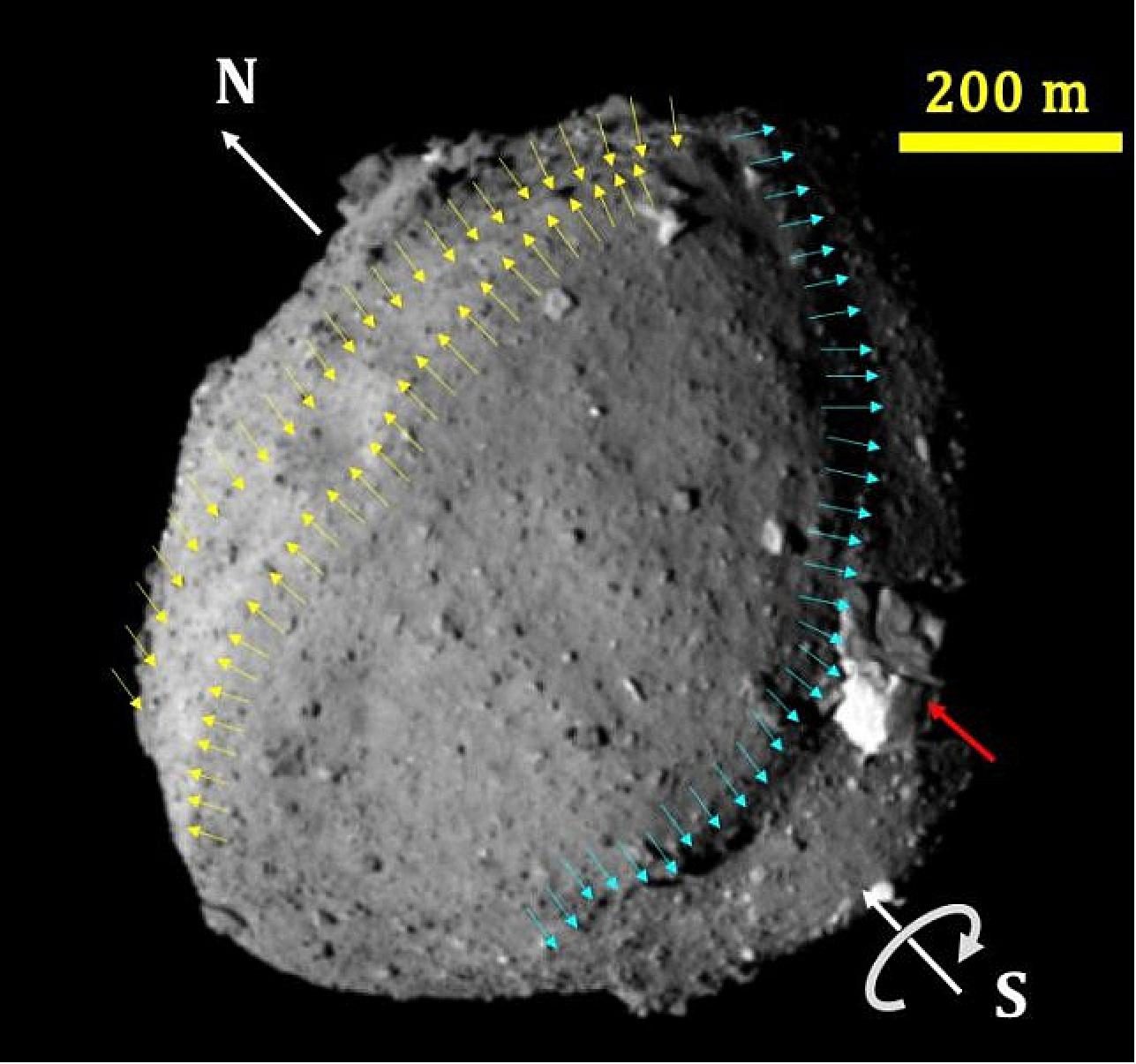

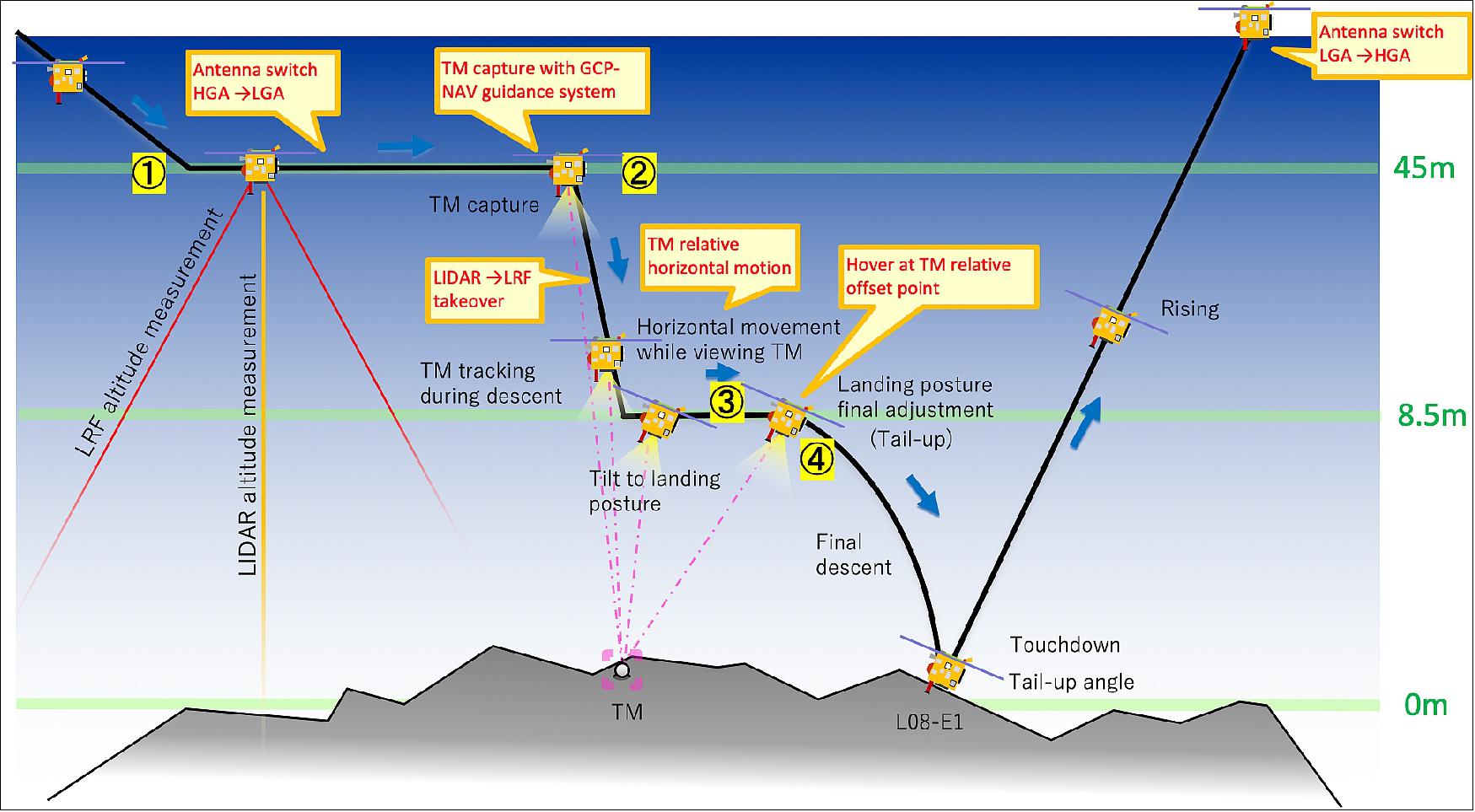

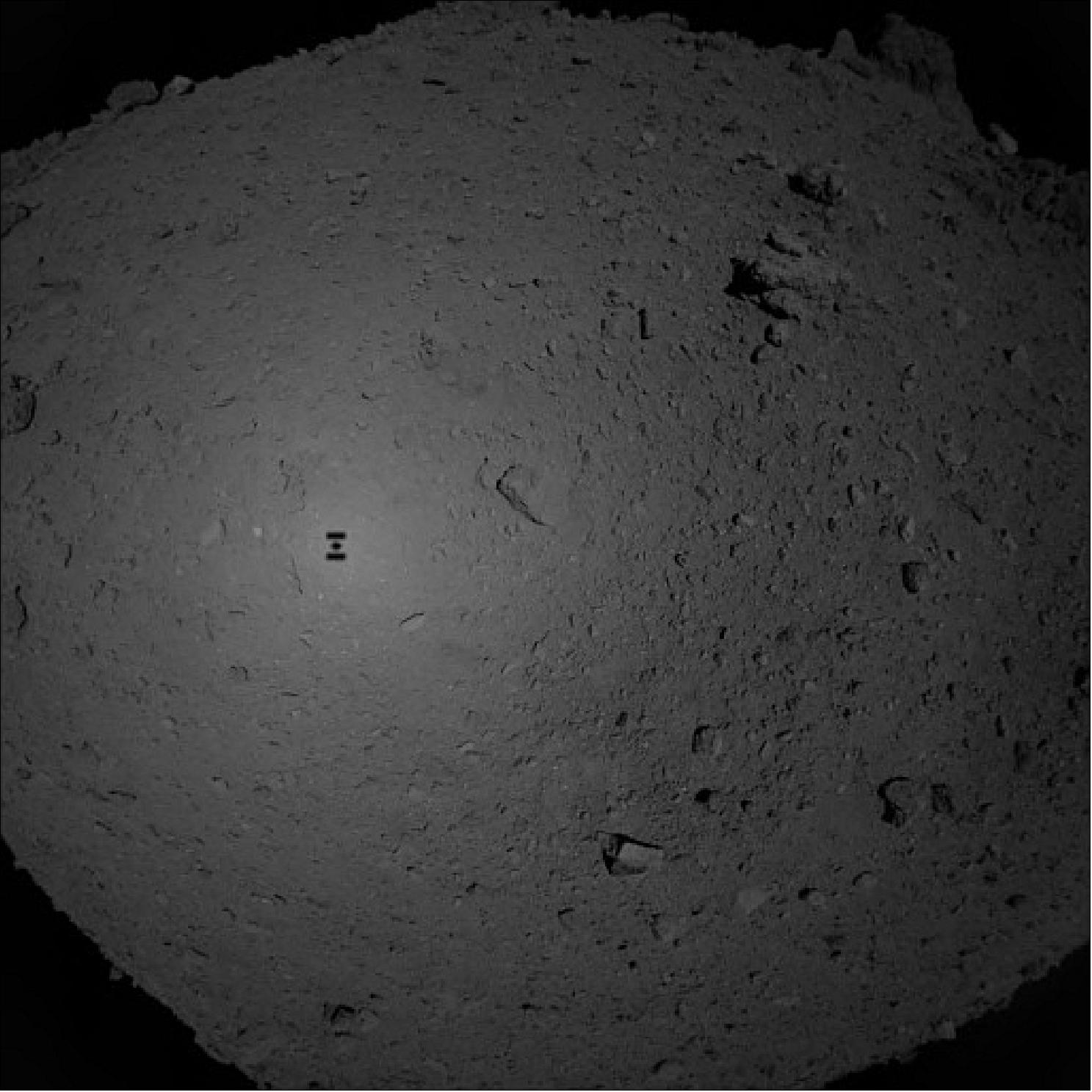

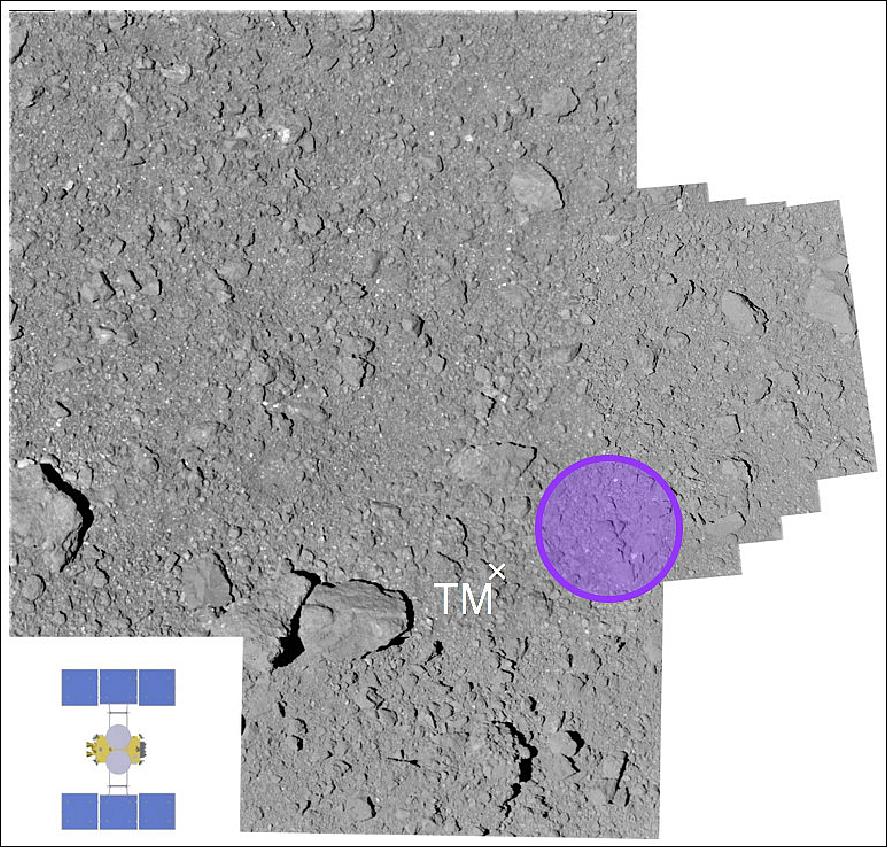

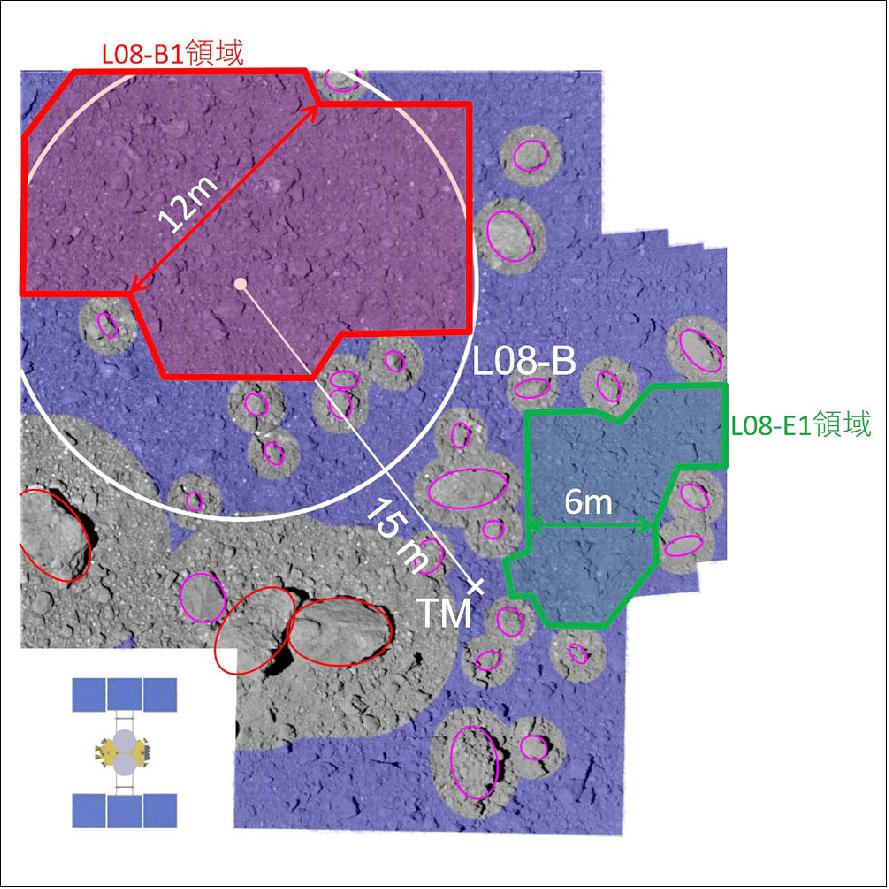

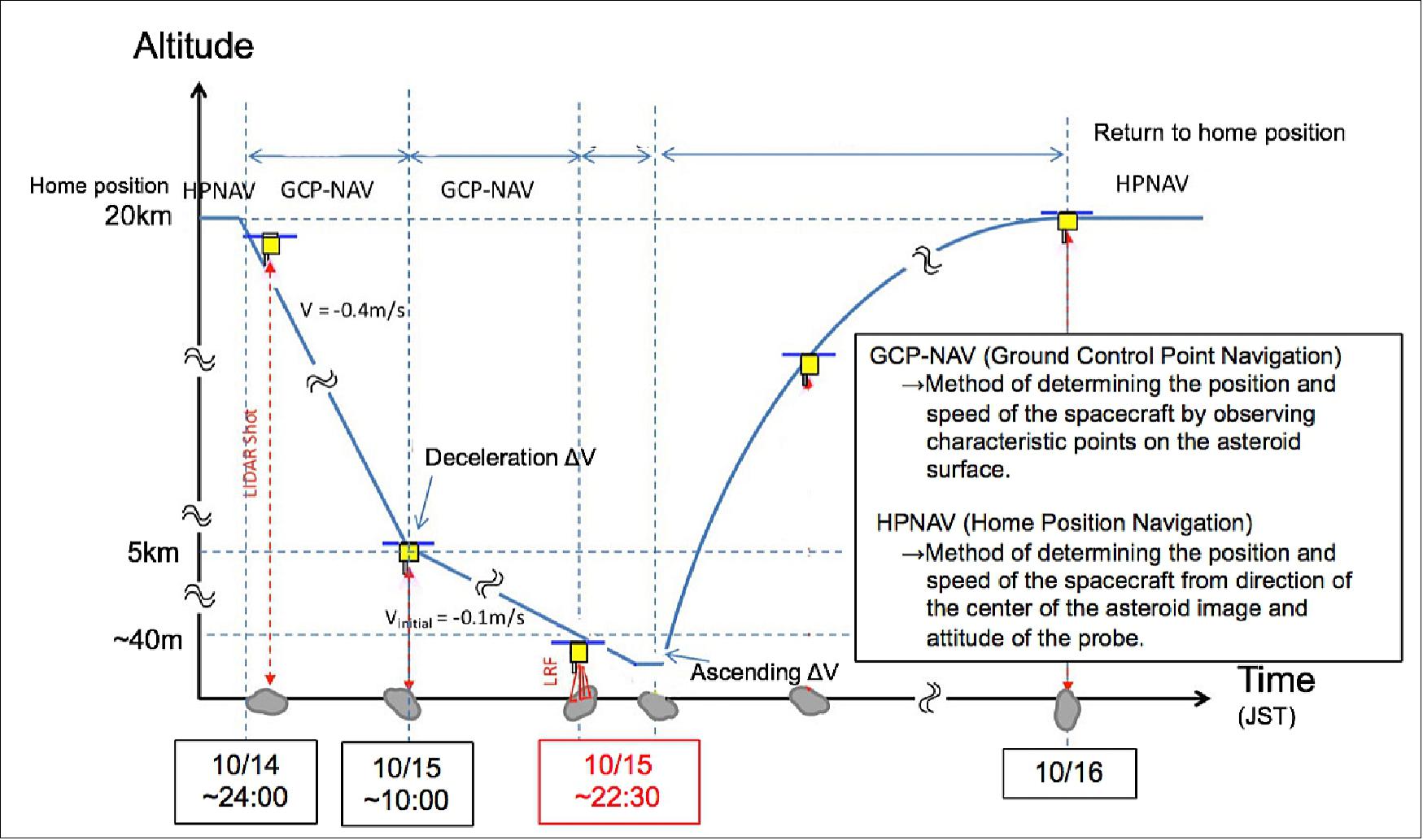

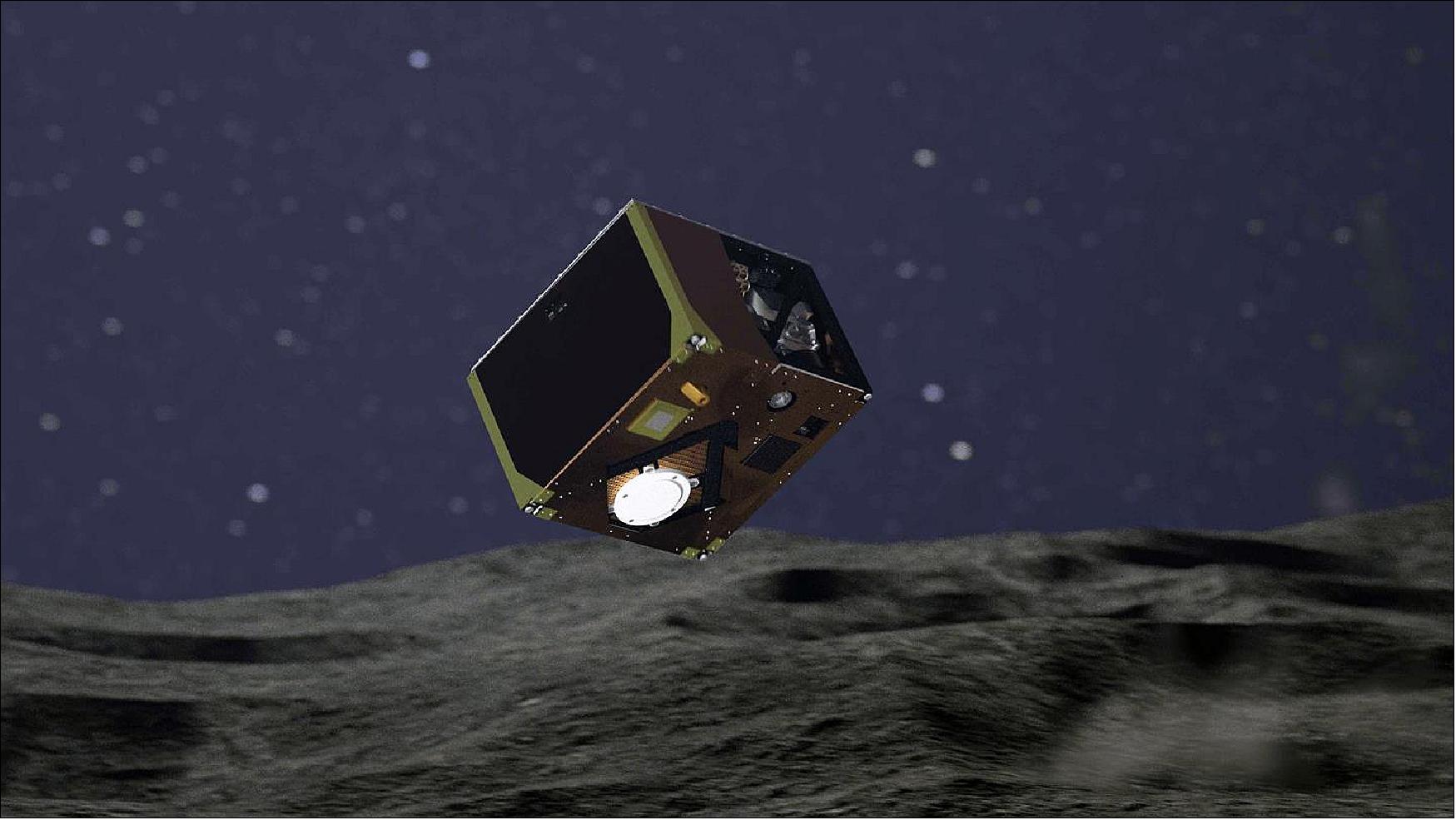

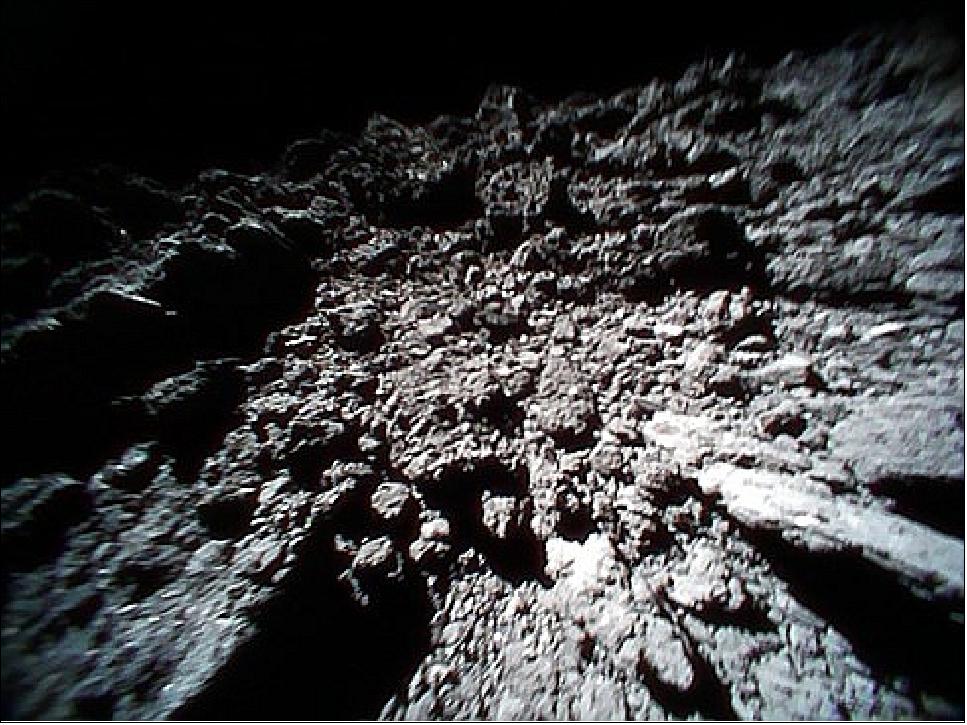

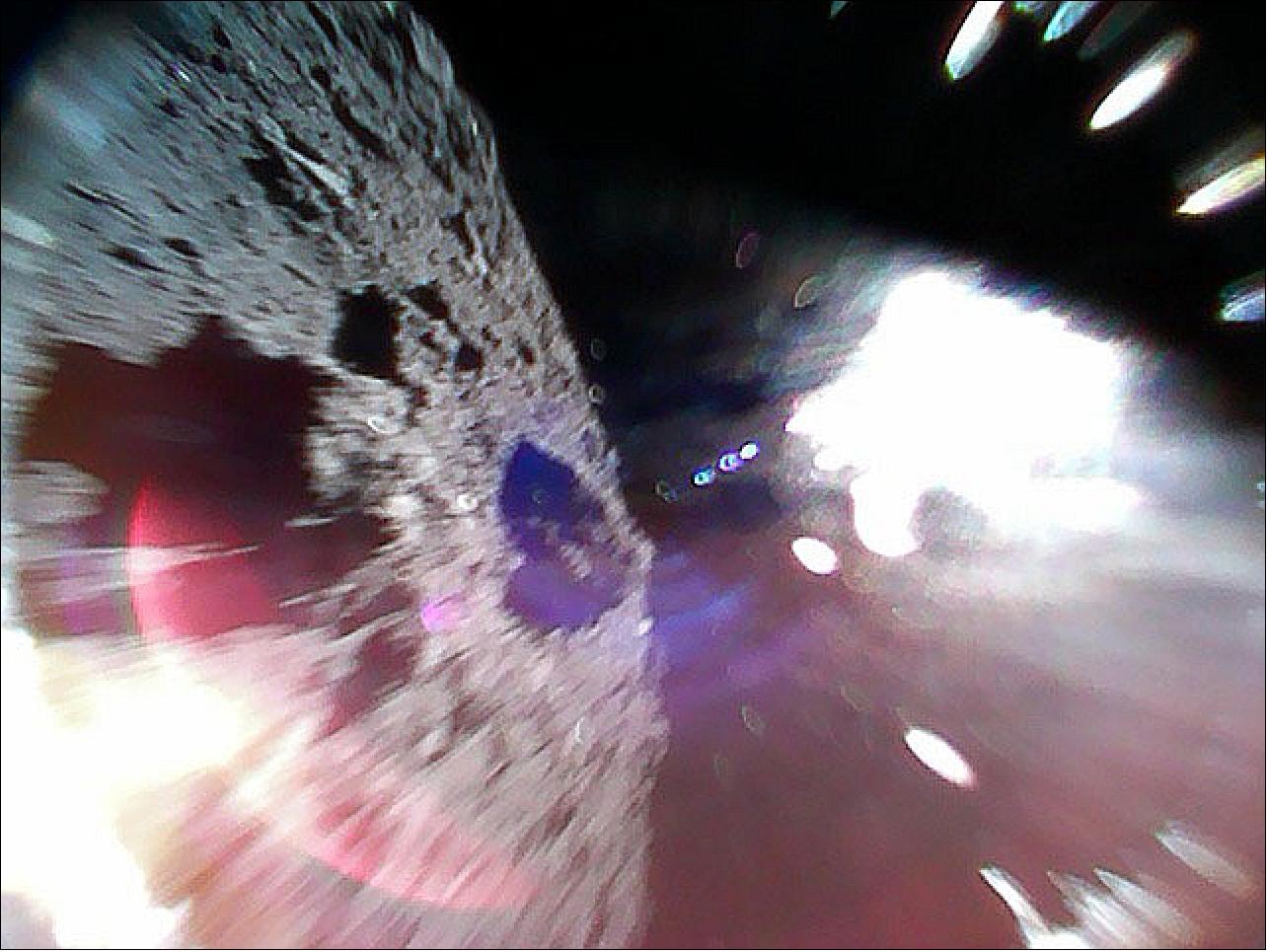

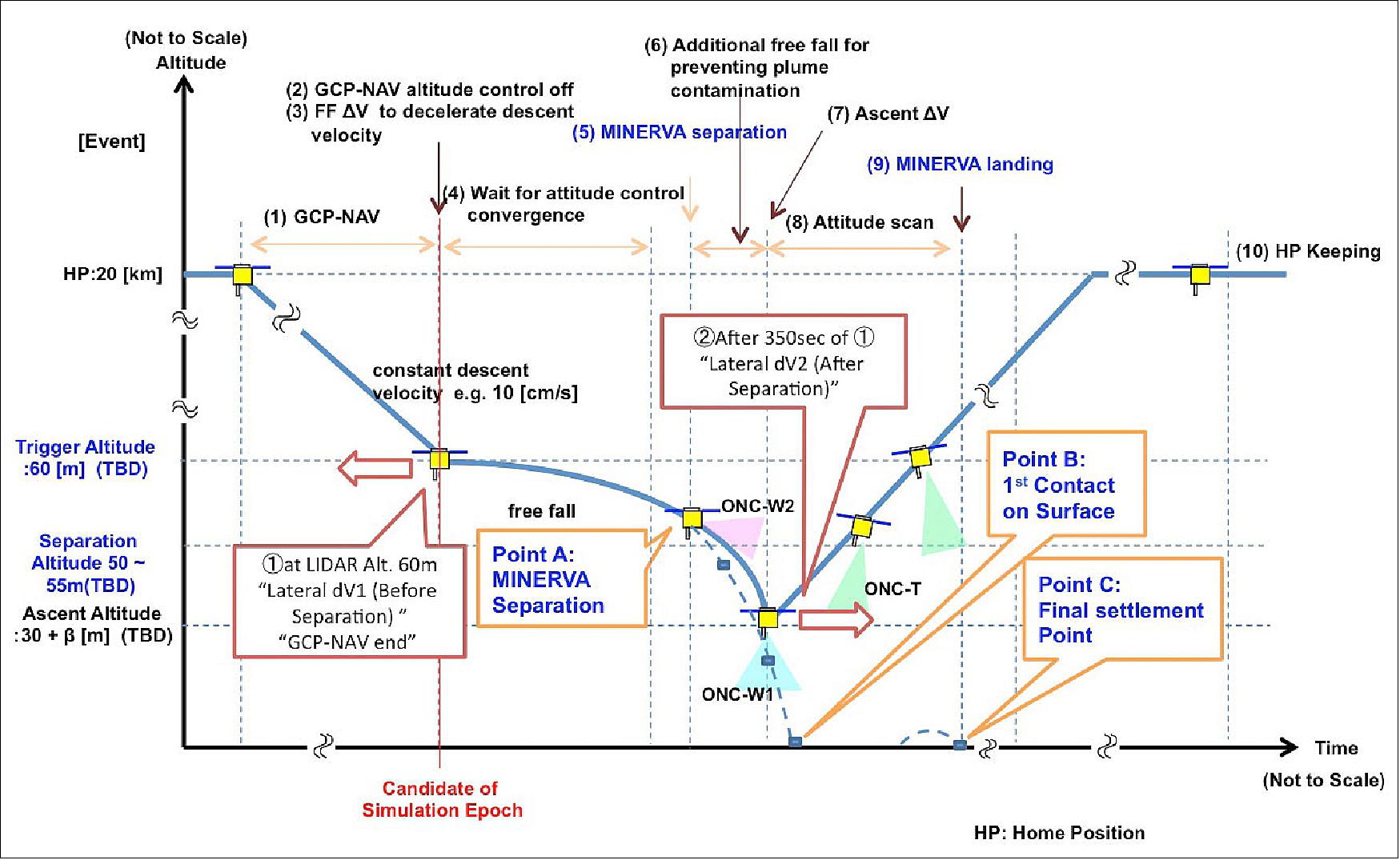

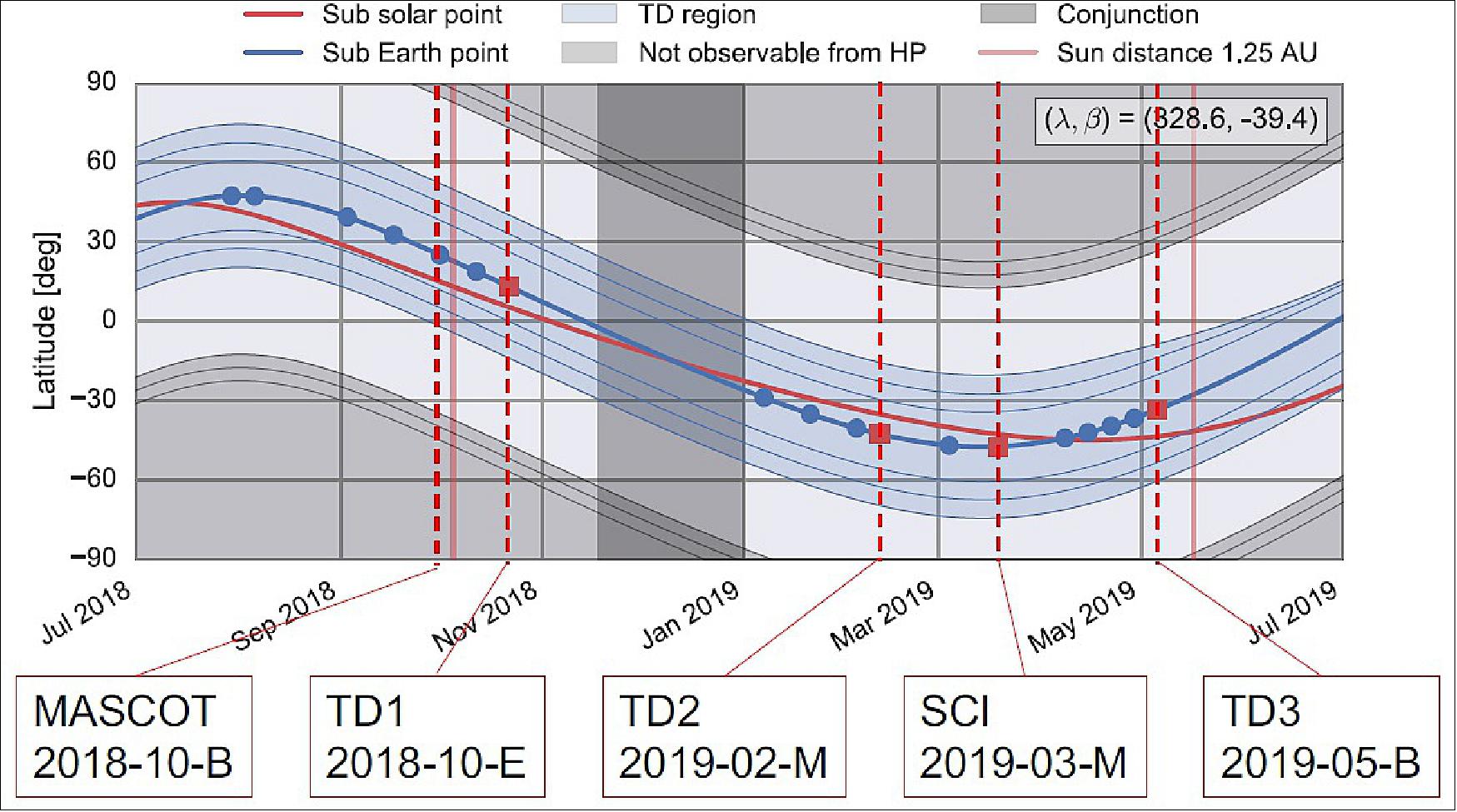

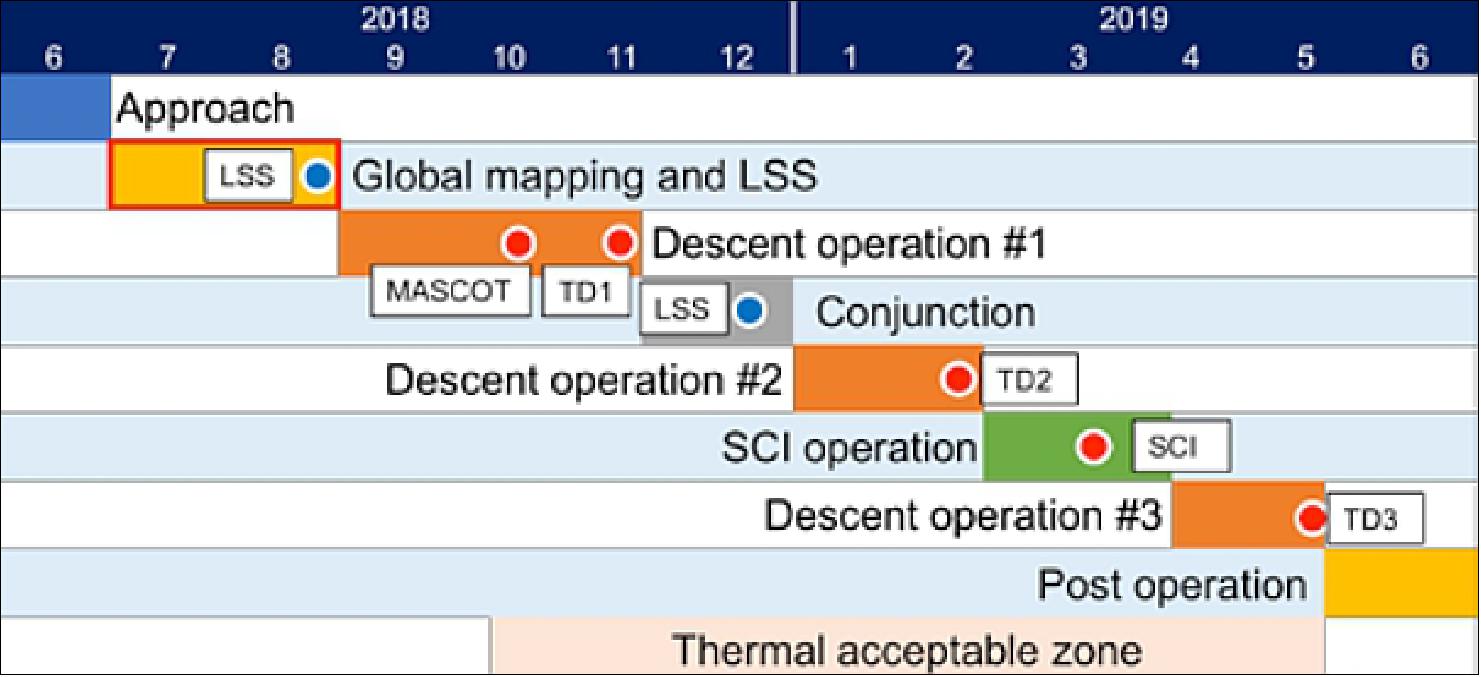

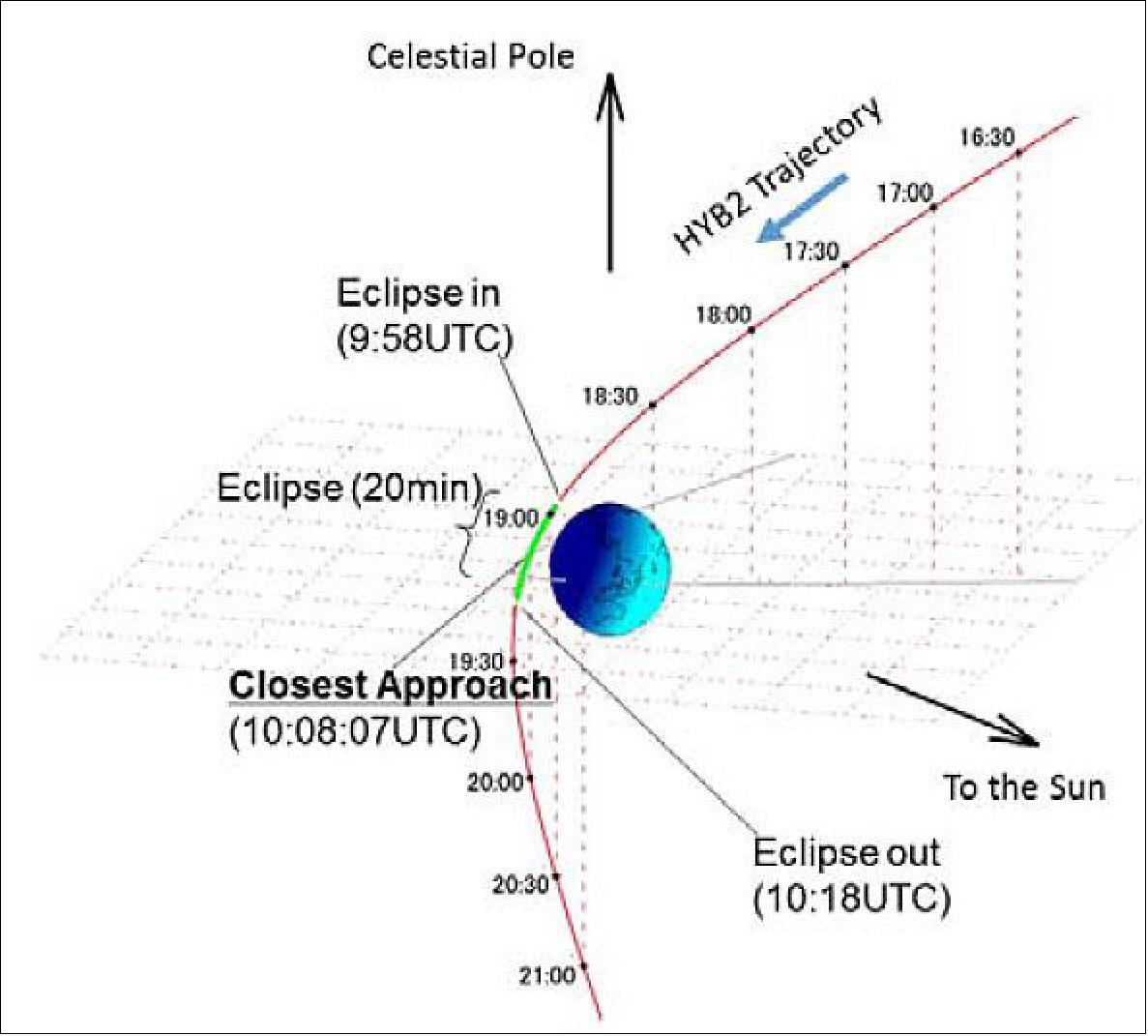

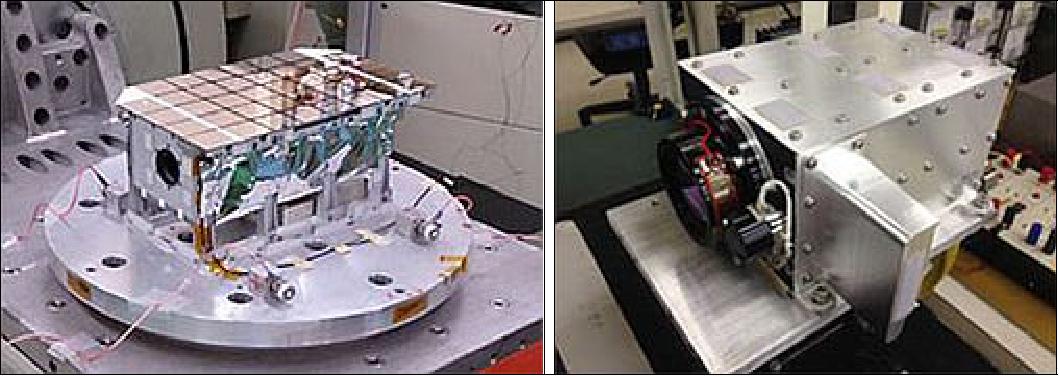

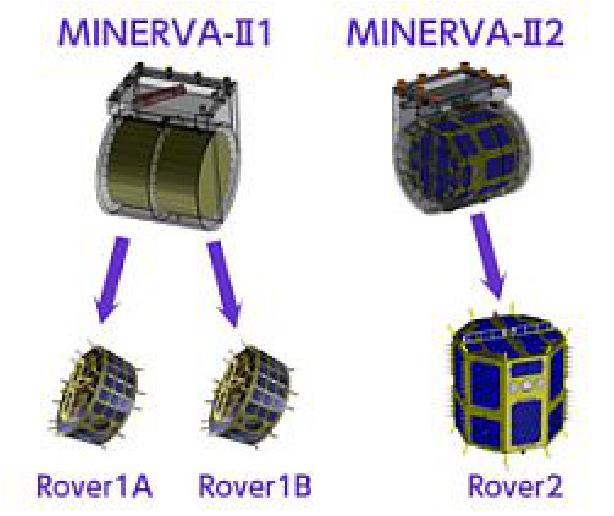

• October 2019: Hayabusa-2 arrived at the C-type asteroid Ryugu in June 2018. During one and a half year of the Ryugu-proximity operation, we succeeded in two rovers landing, one lander landing, two spacecraft touchdown/sample collection, one kinetic impact operation and two tiny reflective balls and one rover orbiting. Among the two successful touchdowns, the second one succeeded in collecting subsurface material exposed by the kinetic impact operation. This paper describes the asteroid proximity operation activity of the Hayabusa-2 mission, and gives an overview of the achievements done so far. Some important engineering and scientific activities, which have been done in synchronous operations with the spacecraft to tackle the unexpected Ryugu environment, are also described. 41)

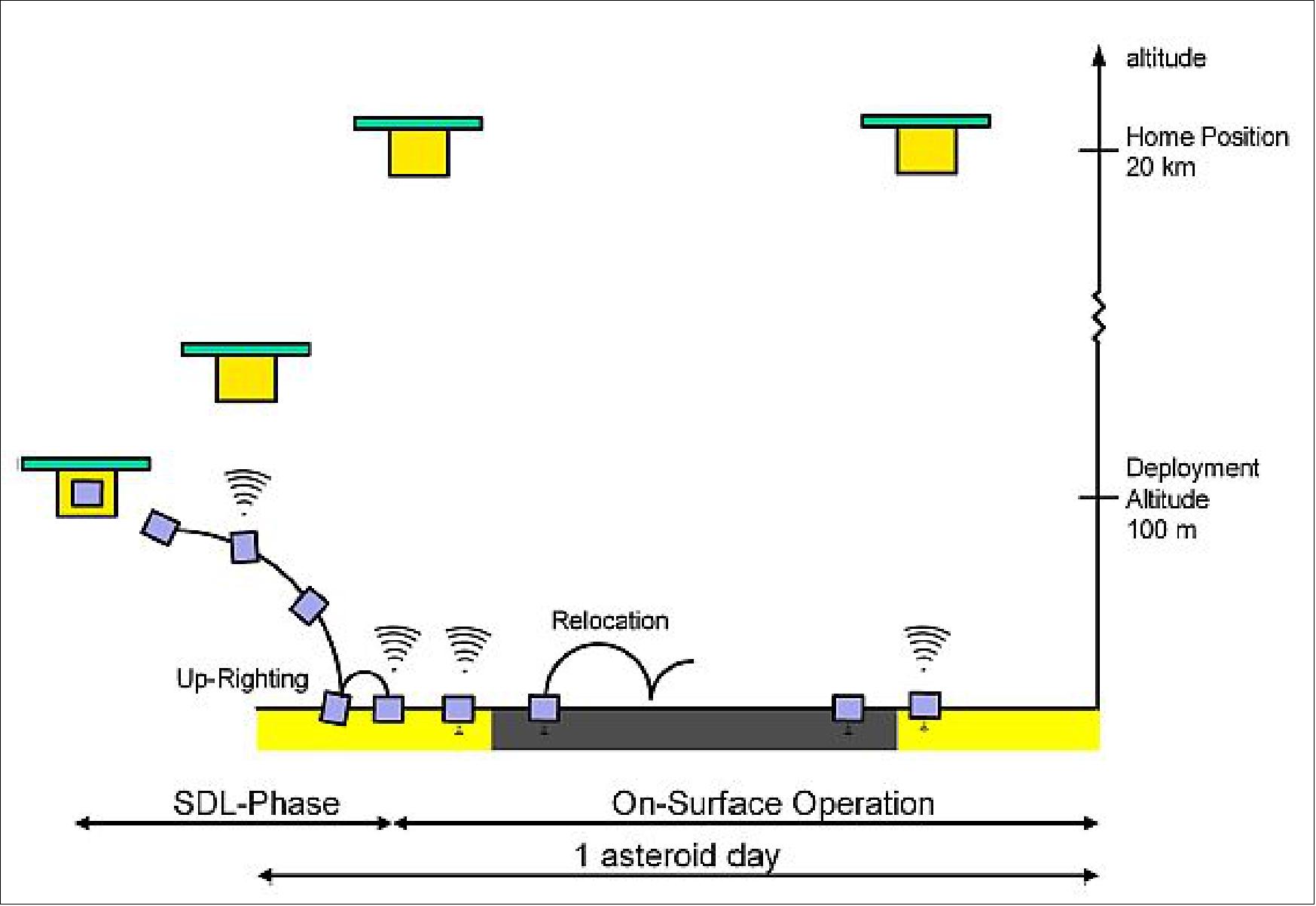

Asteroid Proximity Operation

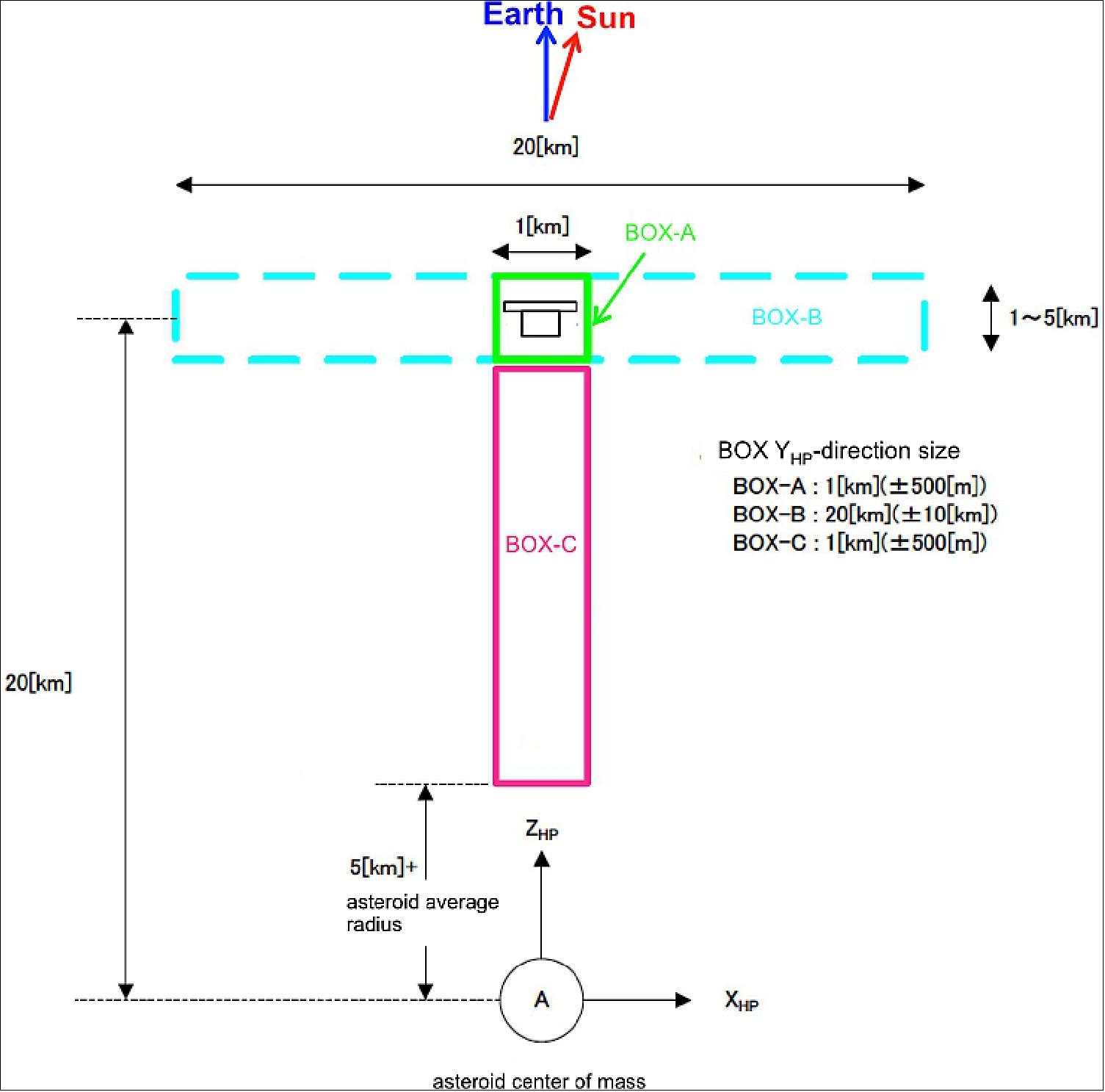

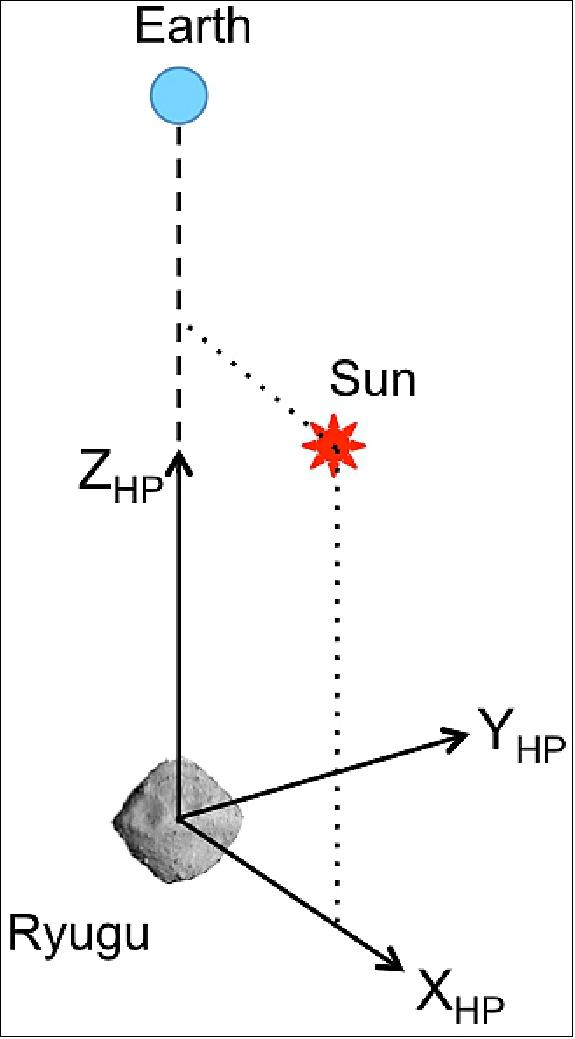

- Summary of Asteroid-Proximity Activity: Hayabusa2 arrived at HP (Home Position) on 27 June 2018, when the asteroid proximity phase began. The HP is defined as the position 20 km from the asteroid center toward asteroid-Earth (sub-Earth) line. The HP is always located on the day side of the asteroid, since the Sun-asteroid-Earth angle varies between 0 to 39º during the 1.5 years of the asteroid proximity phase. The Sun-asteroid distance during the asteroid proximity phase varies between 0.96-1.4AU, and the Earth-asteroid distance varies between 2.0-2.4 AU, which corresponds to the round trip light time of 33-40 minutes.

- All the descent operations to lower altitude is defined as “critical operation” in the project, which were managed by a large operation team participated by 20-40 specifically-trained operators. Table 4 shows the list of the descent operations and the other important operations performed by Hayabusa-2. Overall, the asteroid-proximity activity proceeded as planned despite the fact that the environment of Ryugu was found to be unexpectedly severe, and some operations were aborted (i.e. the spacecraft detected a failure and ascent back to HP while descending).

Year | Date | Event | Status |

2018 | June 3 | Approach Guidance Start (Dist.=3100 km) | Complete |

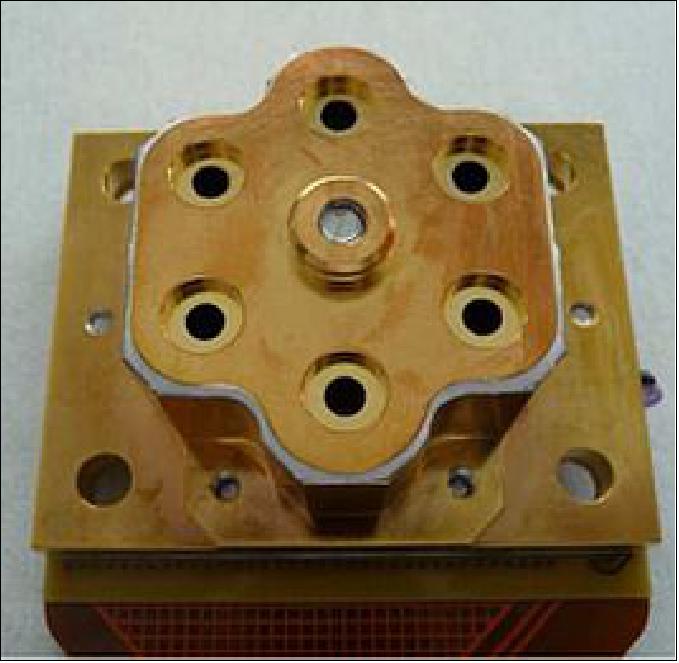

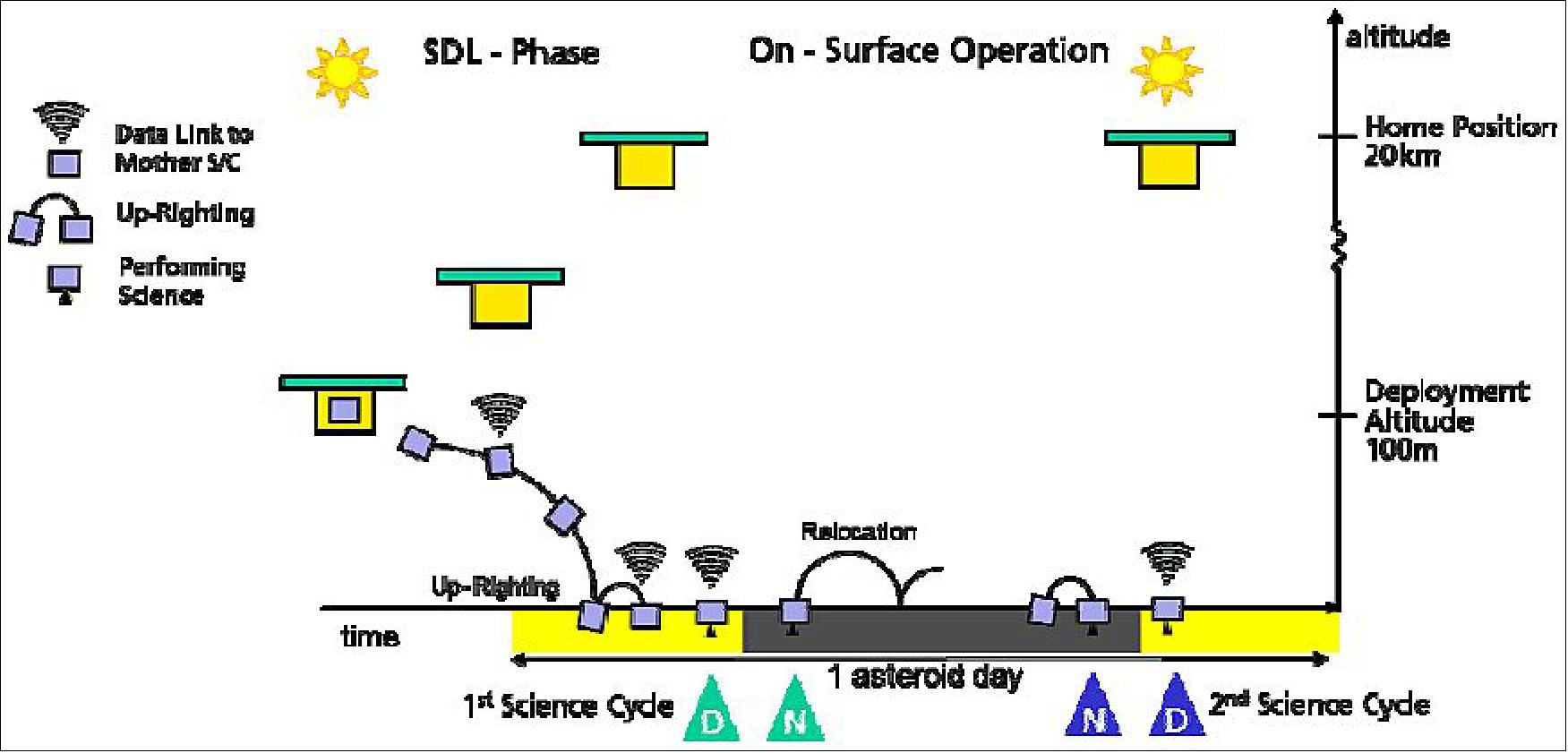

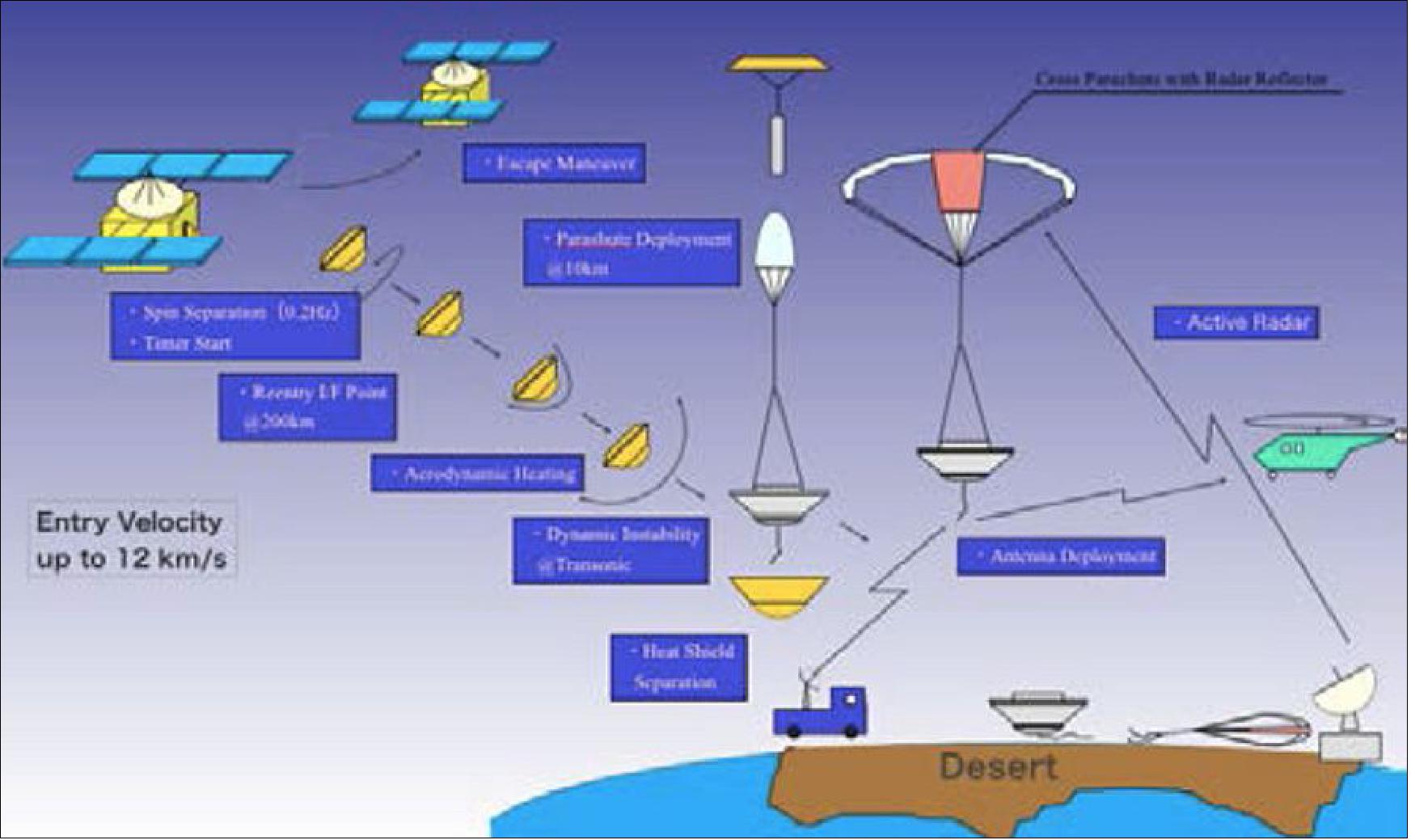

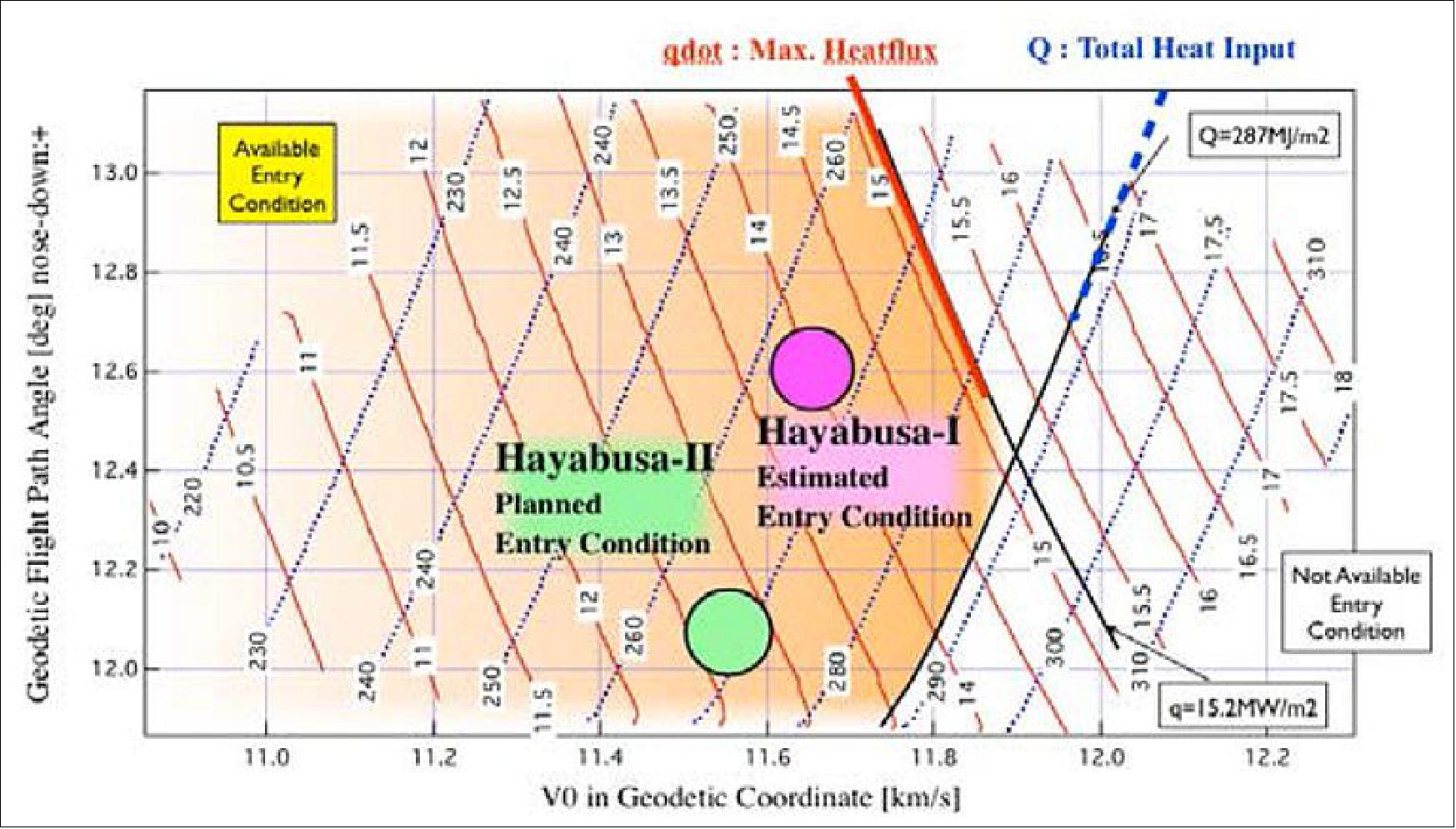

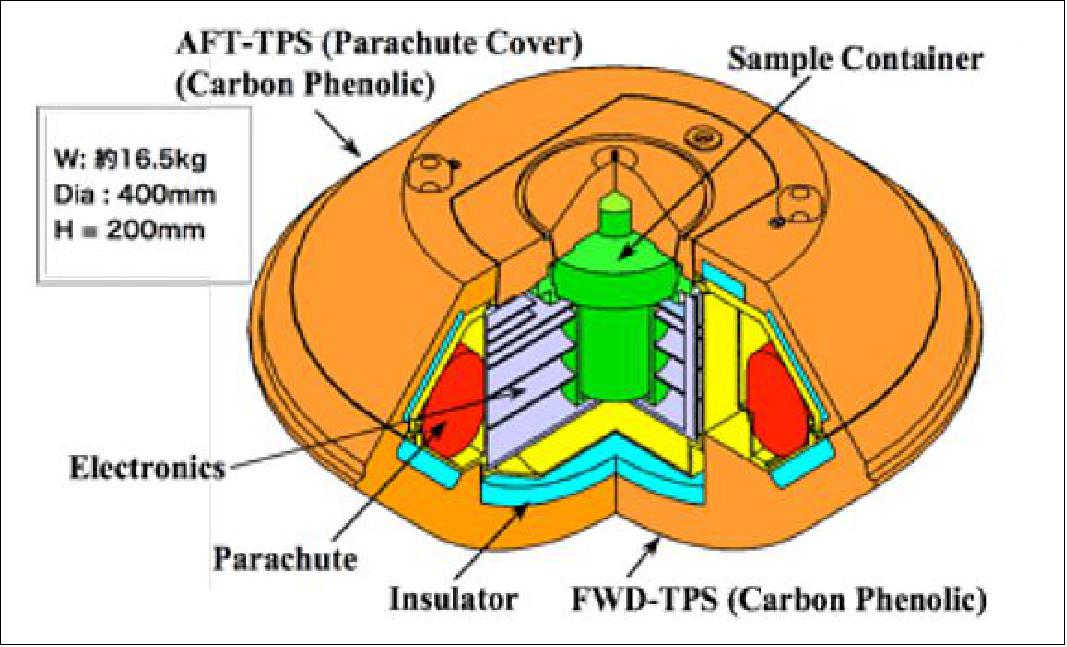

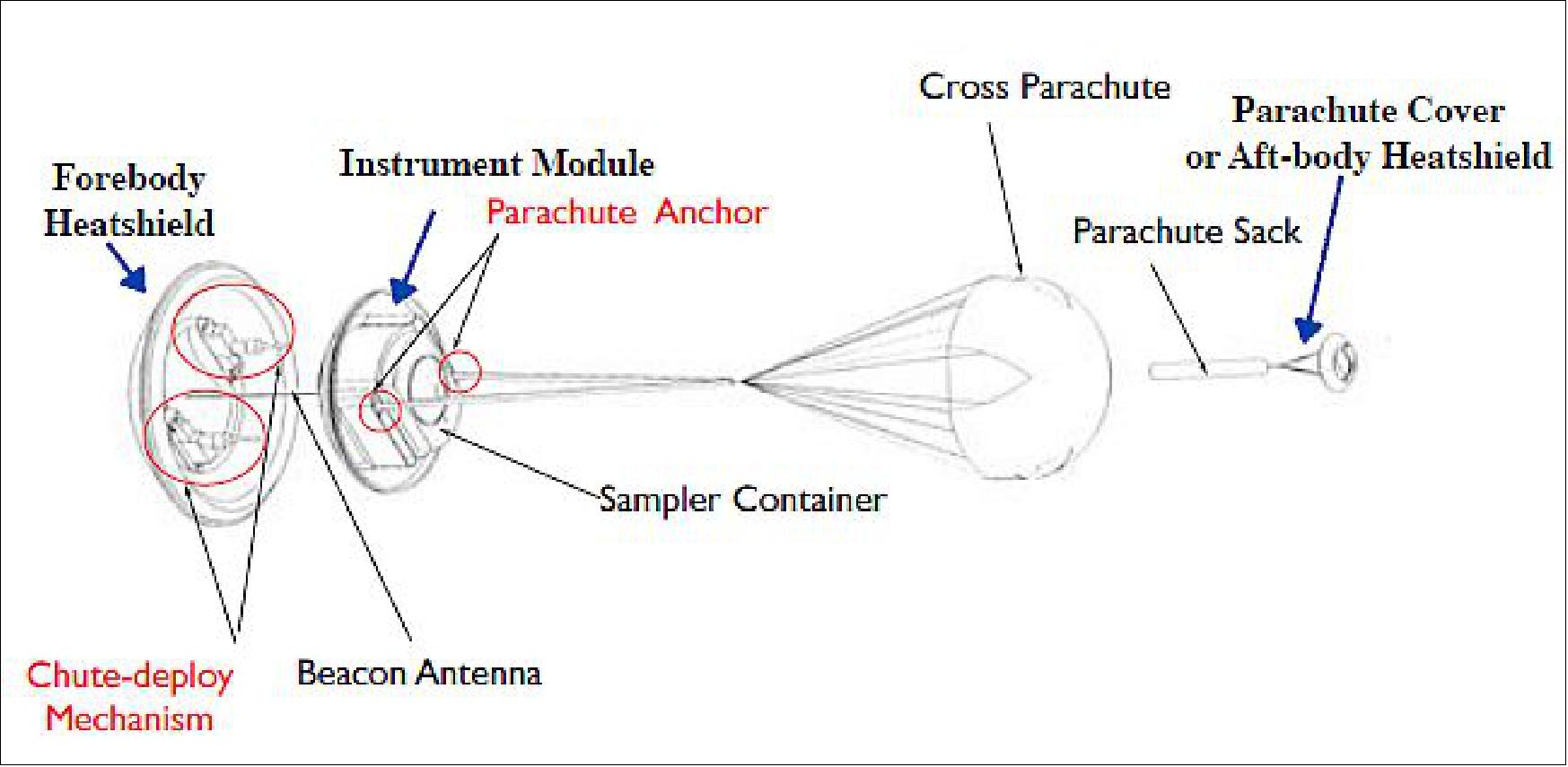

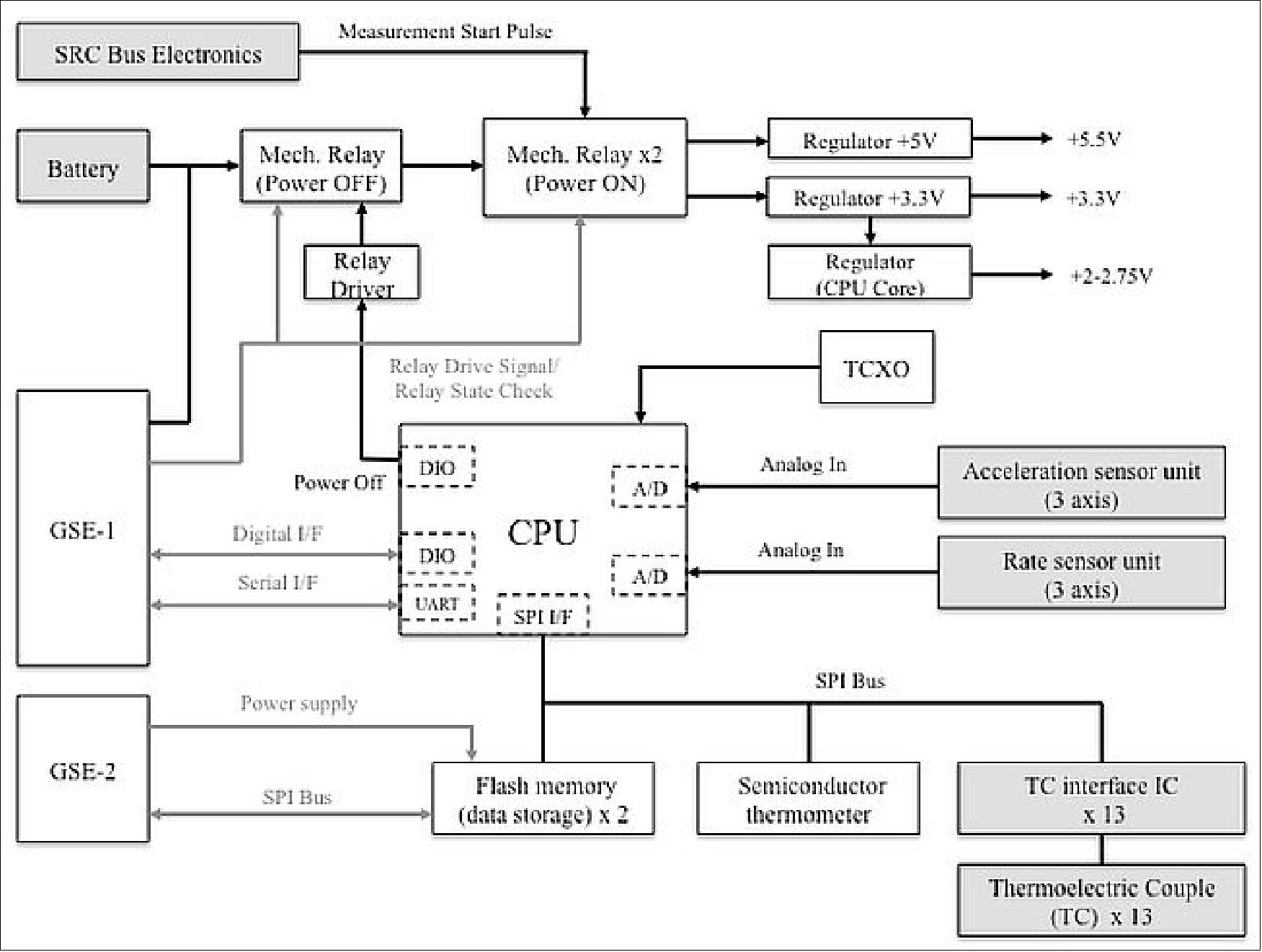

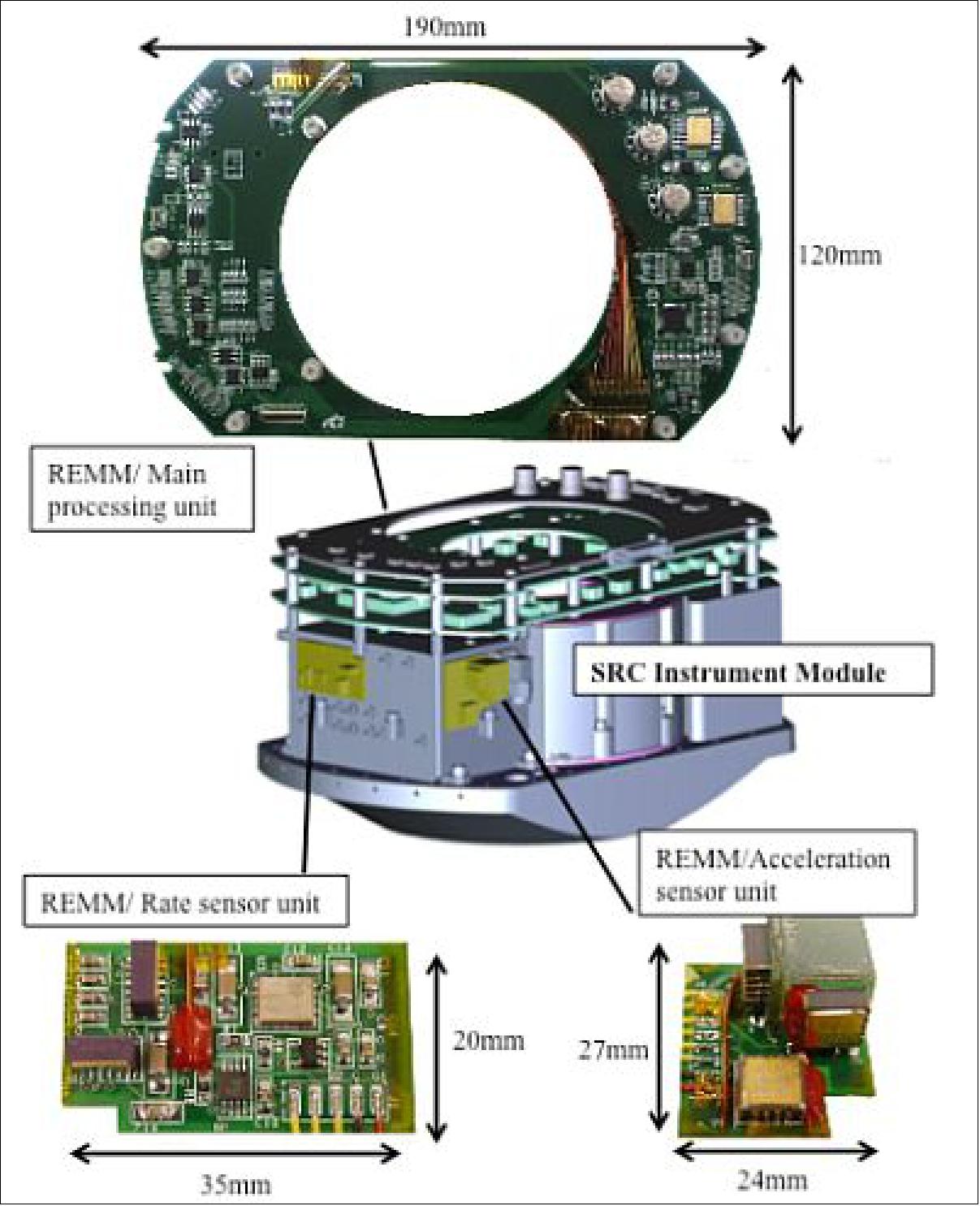

2019 | February 20-22 | [TD1-L08E1] Touch Down Operation 1 | Success |