Landsat-8 - 2017 to 2013

Landsat-8 Imagery in the period 2017 to June 2013

2017 2016 2015 2014 2013 References

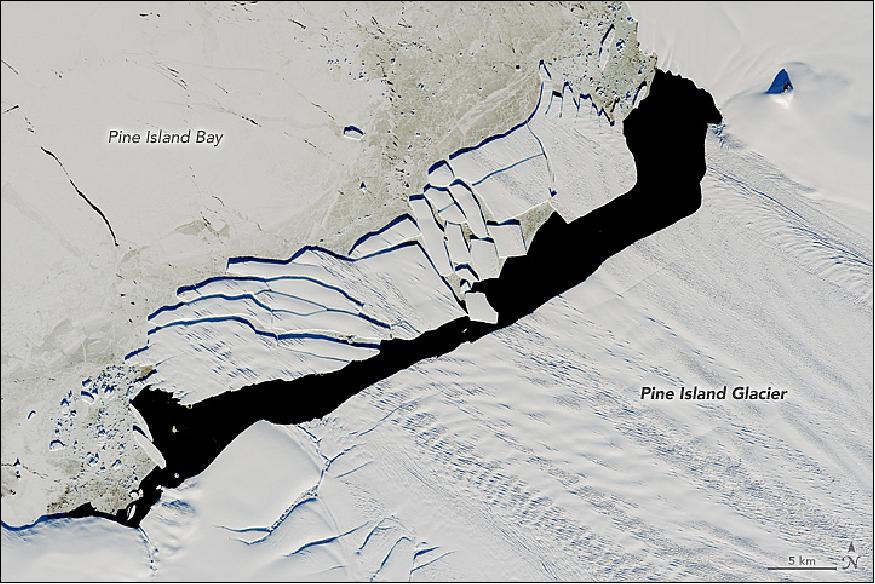

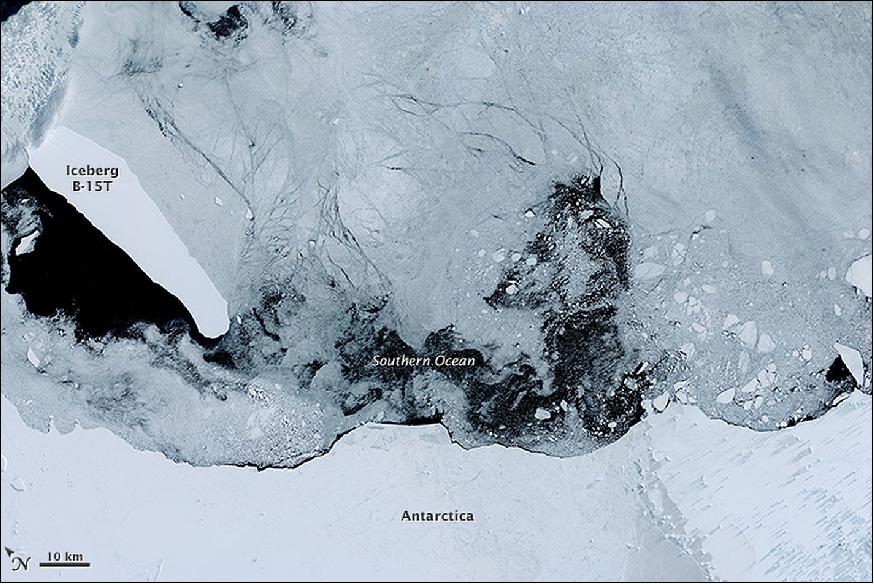

• December 26, 2017: In September 2017, a new iceberg calved from Pine Island Glacier—one of the main outlets where the West Antarctic Ice Sheet flows into the ocean. Just weeks later, the berg named B-44 shattered into more than 20 fragments. 1)

- On December 15, 2017, OLI (Operational Land Imager) on Landsat-8 acquired a natural-color image (Figure 1) of the broken iceberg. An area of relatively warm water, known as a polyna, has kept the water ice free between the iceberg chunks and the glacier front. NASA glaciologist Chris Shuman thinks the polynya's warm water could have caused the rapid breakup of B-44.

- The image of Figure 1 was acquired near midnight local time. Based on parameters including the azimuth of the Sun and its elevation above the horizon, as well as the length of the shadows, Shuman has estimated that the iceberg rises about 49 meters above the water line. That would put the total thickness of the berg—above and below the water surface—at about 315 meters.

• December 24, 2017: Before the opening of the Panama Canal in 1914, Cape Horn was a place that gave mariners nightmares. The waters off this rocky point, at the southern tip of Chile's Tierra del Fuego peninsula, pose a perfect storm of hazards. 2)

- Southwest of Cape Horn, the ocean floor rises sharply from 4,020 m to 100 m within a few kilometers. This sharp difference, combined with the potent westerly winds that swirl around the Furious Fifties, pushes up massive waves with frightening regularity. Add in frigid water temperatures, rocky coastal shoals, and stray icebergs—which drift north from Antarctica across the Drake Passage—and it is easy to see why the area is known as a graveyard for ships.

- Hundreds of ships have gone down near Cape Horn since Dutchman Willem Schouten, a navigator for the Dutch East India Company, first charted a course around the Horn in 1616. One vessel that narrowly escaped that fate was the HMS Beagle, with naturalist Charles Darwin aboard. In 'The Voyage of the Beagle', Darwin described the harrowing journey as the explorers tried to round the Horn just before Christmas 1832.

December 21st. — The Beagle got under way: and on the succeeding day, favored to an uncommon degree by a fine easterly breeze, we closed in with the Barnevelts, and running past Cape Deceit with its stony peaks, about three o'clock doubled the weather-beaten Cape Horn. The evening was calm and bright, and we enjoyed a fine view of the surrounding isles. Cape Horn, however, demanded his tribute, and before night sent us a gale of wind directly in our teeth. We stood out to sea, and on the second day again made the land, when we saw on our weather-bow this notorious promontory in its proper form—veiled in a mist, and its dim outline surrounded by a storm of wind and water. Great black clouds were rolling across the heavens, and squalls of rain, with hail, swept by us with such extreme violence, that the Captain determined to run into Wigwam Cove. This is a snug little harbor, not far from Cape Horn; and here, at Christmas-eve, we anchored in smooth water. The only thing which reminded us of the gale outside, was every now and then a puff from the mountains, which made the ship surge at her anchors. |

• December 15, 2017: For more than a hundred years, the fertile and forested patch between the Tennessee and Cumberland rivers was referred to as the "land between the rivers." In the 1960s, it became the "land between the lakes." 3)

- In an attempt to control flooding and to generate electricity in rural Kentucky and Tennessee, the TVA (Tennessee Valley Authority) built Kentucky Dam, thereby impounding the Tennessee River and creating Kentucky Lake in 1944. It became the largest manmade lake east of the Mississippi River.

- Two decades later, the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers blocked the flow of the nearby Cumberland River as well. With the completion of Barkley Dam in 1966, the waters of the Cumberland piled up into Lake Barkley. In the process of creating the two lakes, residents of several small towns along and between the rivers were moved, and parts of some towns were permanently flooded. A few local roads and railways had to be re-routed.

- Engineers also dug out Barkley Canal in order to bring the two rivers and lakes to the same water level. This allowed ships and barges to more easily move goods (without locks) from the Cumberland and Tennessee river valleys toward the mighty Mississippi River. By the time they were done, the TVA and Army Corps had created one of the largest inland peninsulas in the United States.

- In the years after the lakes were created, the new peninsula was slowly converted into a recreation area for hunting, fishing, boating, hiking, and camping. Now managed by the U.S. Forest Service, the Land Between the Lakes National Recreation Area includes one of the largest freshwater recreation complexes in the United States. The parkland and lakes attract roughly two million visitors per year. The Operational Land Imager (OLI) on Landsat 8 acquired this natural-color image of the region on October 7, 2016.

- Near Golden Pond, some forests have been cleared and re-seeded to return the land to what it likely looked in the 19th century. That grassland prairie also has been settled with elk and bison that once roamed the region. Recreational facilities also include a planetarium and a woodlands nature station. At the southern end of Land Between the Lakes, near the town of Dover, a re-creation of an 1850s homestead includes rare breeds of livestock and plants from that era.

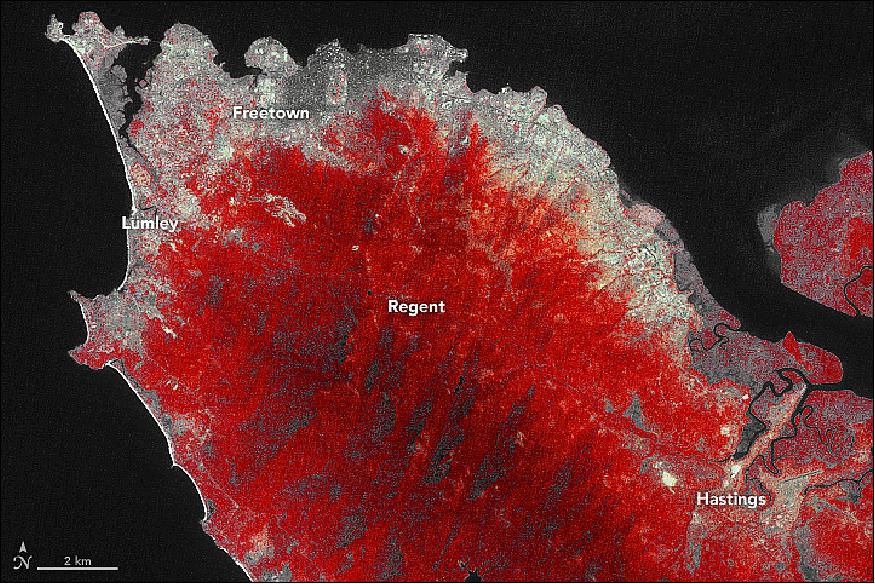

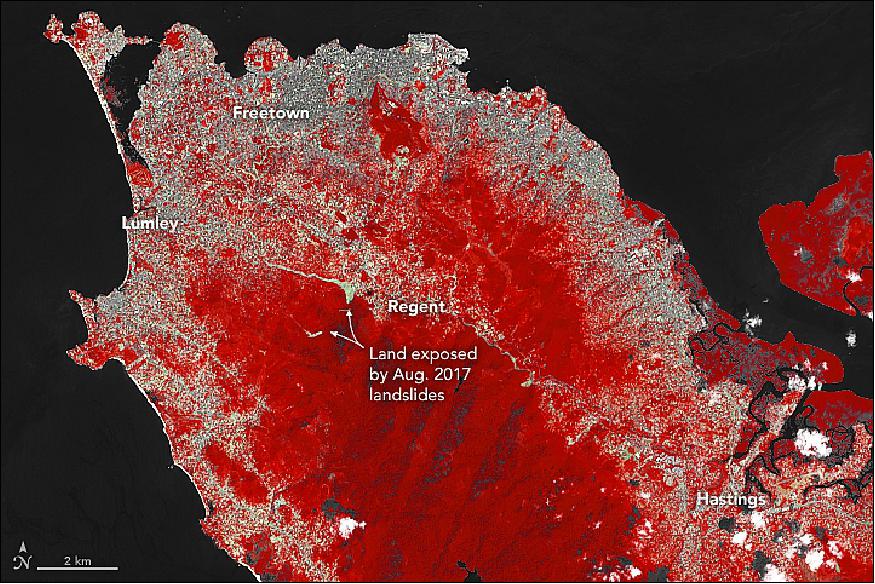

• December 5, 2017: At 6:50 a.m. on August 14, 2017, the people of Regent heard a low rumbling noise like the hum of a passing airplane. Then there was quiet. A hillside had failed in this mountainous area just beyond Freetown, Sierra Leone (Africa, located on the Atlantic Ocean). 4)

- Ten minutes later, an explosive sound came from the direction of nearby Mount Sugar Loaf. The Earth trembled and began to flow. Trees and boulders of all sizes tumbled chaotically. Sparks lit the morning air as metal and rock collided. A river of rust-colored soil plunged into the swollen stream valleys below, which were already filled with floodwater due to several days of intense rain. A destructive slurry of mud, boulders, and tree parts rushed down toward the stream valley, flowing more than three kilometers before draining into the sea near Lumley.

- When authorities tallied the loss of life and property, the numbers were sobering. More than 1,141 people died and 3,000 people lost their homes, according to a World Bank assessment. Damage to homes in the area totaled more than $14 million.

- Sustained downpours were the immediate trigger for the landslide. Between July 1 and August 14, Freetown received 1,040 mm of rain—about three times the norm for that period. However, decades of rapid urbanization in landslide-prone areas, as well as construction along streams where flooding was common, set the stage for the disaster. Joseph McCarthy, an urban planner at Njala University, went so far as to tell Thompson Reuters that: "The major cause of mudslides and flooding is the chaotic development caused by the rapid urbanization of Freetown."

- This pair of false-color Landsat images (Figures 5 and 6) illustrates the extent of the changes. Forested areas appear red, urban areas are gray, and landslide debris is tan. In 1986, most of the development was in low-lying, coastal areas. By 2017, development had spread widely into mountainous areas. For instance, the town of Regent had just a handful of buildings in 1986. By 2017, it had many more buildings and a population of 28,000 people.

- In addition to the spread of urban areas, the images also highlight the extent of deforestation—one of the factors that helps trigger landslides—to the south of Freetown. According to one analysis of Landsat imagery led by Lamin Mansaray of Zhejiang University, the Freetown region saw its densely forested areas drop from 113 km2 in 1986 to 59 km2 in 2015 — a 52 percent decline.

- The city's population increased from about 500,000 people in 1986 to about 1 million people today. A civil war between 1991–2002 accelerated the city's expansion. "Before 1991, there was minimal rural-urban migration in Sierra Leone. During the conflict, rural areas were most vulnerable to attacks, and Freetown was by far the safest place to be," explained Mansaray. "After the war ended in 2002, migration into the capital remained high because most people in rural areas had lost their homes and sources of livelihoods."

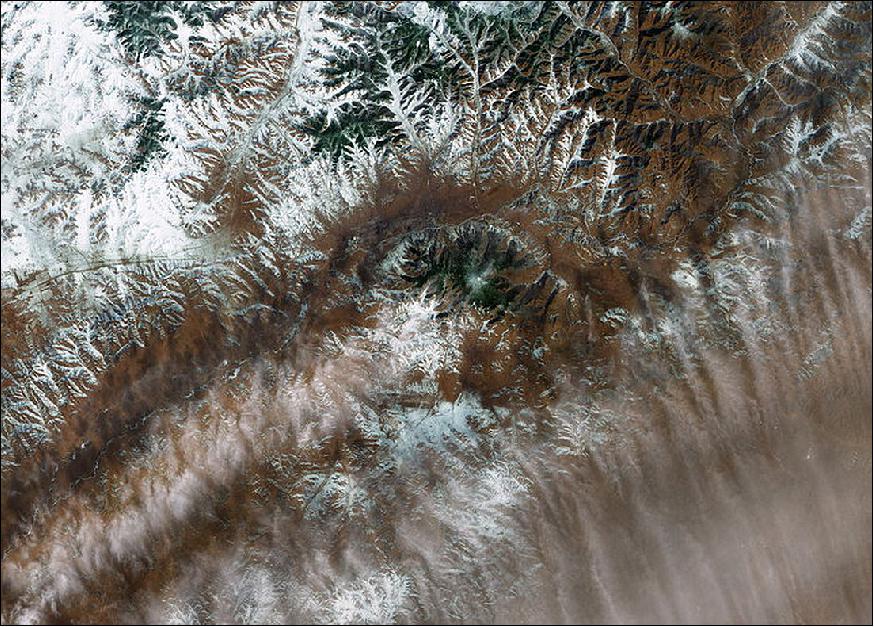

• December 2, 2017: In central Algeria, just above the Tropic of Cancer and about 1200 km south of the Algiers metropolis, lies a land as desolate as it is beautiful. 5)

- In this part of the Sahara, known as the Tanezrouft Basin, the land is especially parched, with annual rainfall measured in mm (less than 5 mm). This is a hyperarid place of soaring temperatures and scarce access to water or vegetation. There are no permanent residents here, only occasional Tuareg nomads. The basin's colloquial name is the "Land of Terror" because, for many, to traverse this land is to stare death in the face.

- The severe conditions that make this basin a barren expanse for life also lay bare its exquisite geology. Wind erosion—caused by constant sandblasting through millennia of frequent sandstorms—has exposed ancient folds in the Paleozoic rocks. This natural-color image, acquired on October 22, 2017, by OLI (Operational Land Imager) on Landsat 8, shows concentric rings of exposed sandstone strata that create stunning patterns across the Tanezrouft Basin. When viewed from 705 km above Earth, the exposed geologic features create an arresting work of abstract art.

- The sandstone canyons in this region have walls that rise as high as 500 m, and salt flats can be found in their lower reaches. The flats indicate that water played a role in sculpting this landscape. "Intermittent flooding has occurred often enough to mold the landscape pretty thoroughly over millions of years," explained P. Kyle House, a geologist with the U.S. Geological Survey. "There are numerous canyons in this region that both follow and abruptly cut directly across the grain of the tilted and folded strata," he added. "These patterns are striking and reminiscent of landscapes formed on folded strata in, for example, the Red Desert of southern Wyoming and even parts of the heavily forested Appalachian Mountains of the Eastern United States."

- On the ground, life is a rare. About 80 km east of this area, the trans-Saharan highway—known as one of the world's most brutal roads—makes its way through the desert.

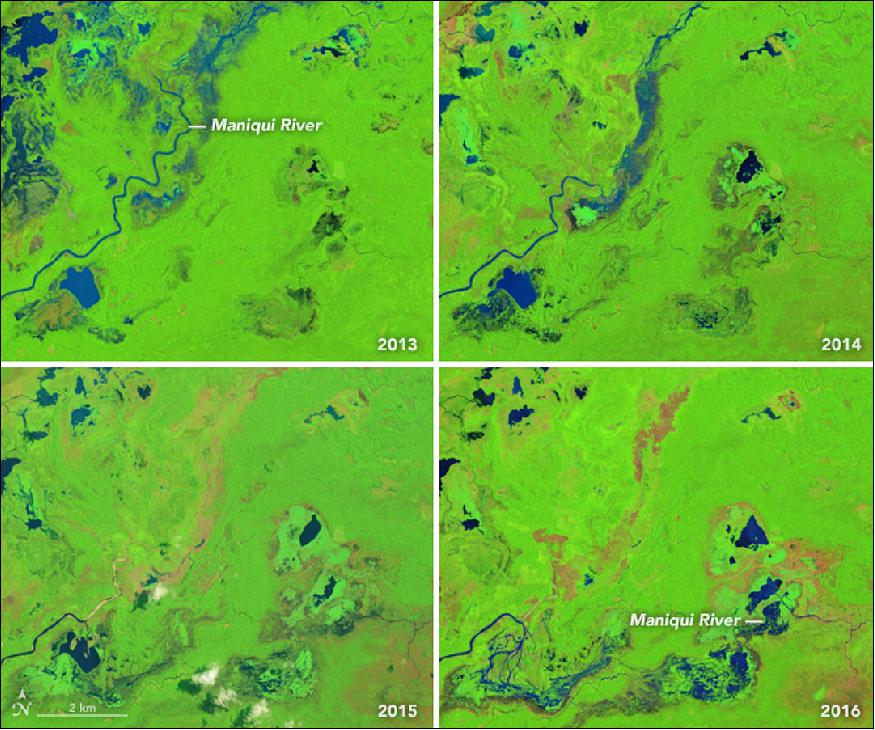

• November 25, 2017: Lake Chad sustains people, animals, fishing, irrigation, and economic activity in west-central Africa. But in the past half century, the once-great lake has lost most of its water and now spans less than a tenth of the area it covered in the 1960s. Scientists and resource managers are concerned about the dramatic loss of fresh water that is the lifeblood of more than 30 million people. 6) 7)

- Lake Chad sits within the Sahel, a semiarid strip of land dividing the Sahara Desert from the humid savannas of equatorial Africa. The Chad Basin is bordered by mountain ranges and spans more than 2.4 million km2 of Cameroon, Nigeria, Chad, and Niger. The water level is largely controlled by the inflow from rivers, notably the Chari River from the south and, seasonally, the Komodugu-Yobe from the northwest. Rainfall can also reach the lake by way of smaller tributaries and groundwater discharge.

- Inflow fluctuates with the shifting patterns of rainfall associated with the West African Monsoon, making the system very sensitive to drought. Most precipitation in the Sahel falls during the peak of a short rainy season from July through September. The dry season is most intense between November and March. Years with little precipitation can wreak havoc on the water supply.

- Extreme swings in Lake Chad's water levels are not new. The lake has experienced wet and dry periods for thousands of years, according to paleoclimate research. More recently, variations in depth and extent were noted by French explorer Jean Tilho, who reported in 1910 that parts of the lake had dried up. But what is new is the way researchers are studying changes in the lake.

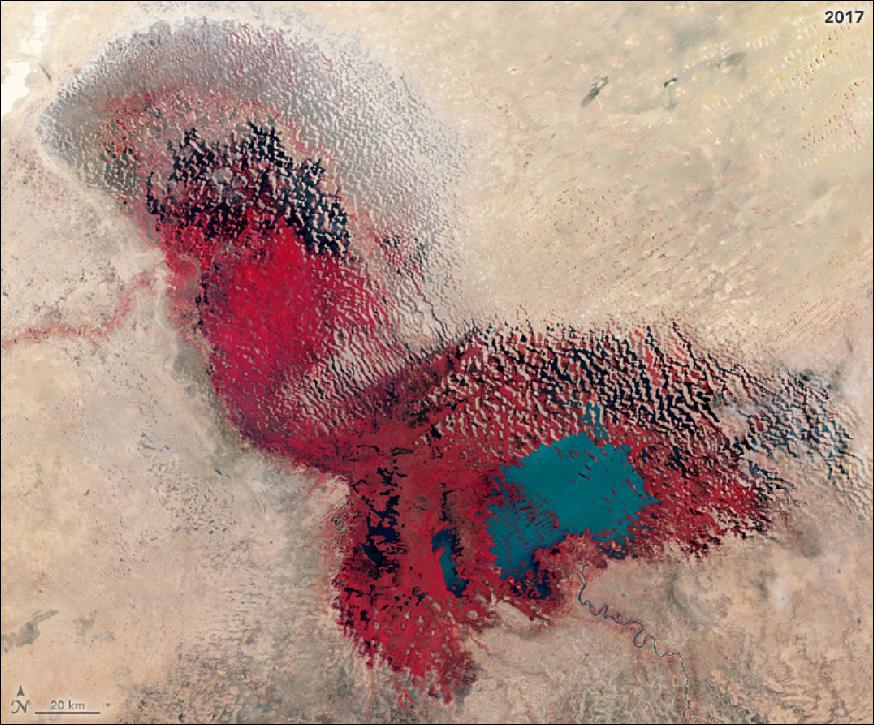

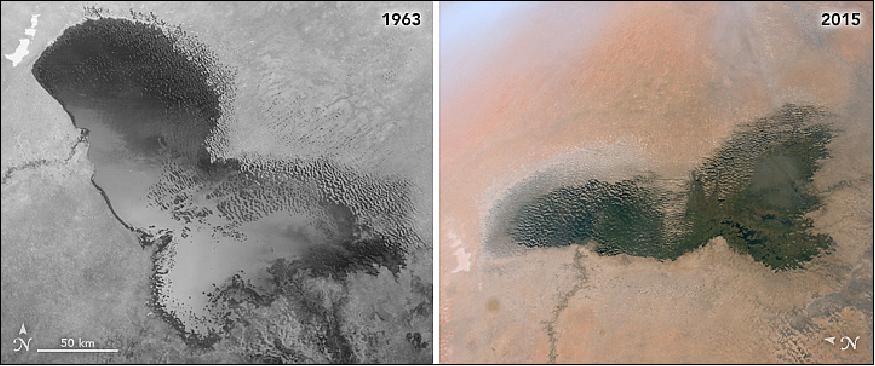

- The images of Figures 8 to 10 highlight the shrinking and growing in the recent life of Lake Chad. The false-color images were acquired by Landsat satellites—Landsat-1 in 1973 and Landsat-8 in 2017. The combination of visible and infrared light helps to better differentiate between vegetation (red) and water (blue and slate gray). The photographs of Figure 10 were captured by the Corona reconnaissance satellite in 1963 and by an astronaut on the International Space Station in 2015.

- In 1973, the lake was in a phase called "Normal Lake Chad"—a single body of water with an archipelago on the north side of the southern basin. Note how little vegetation was around the lake at that stage. Throughout the 1970s, severe droughts plagued the African Sahel, and water disappeared from the northern basin. Since then, water has come and gone from the northern lobe depending on the year and season. But the two lobes have never reconnected into a single lake.

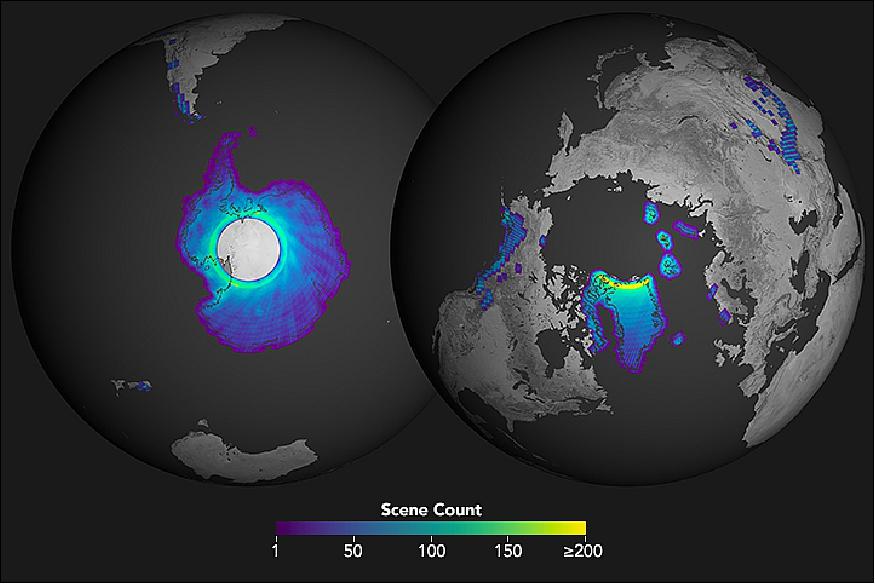

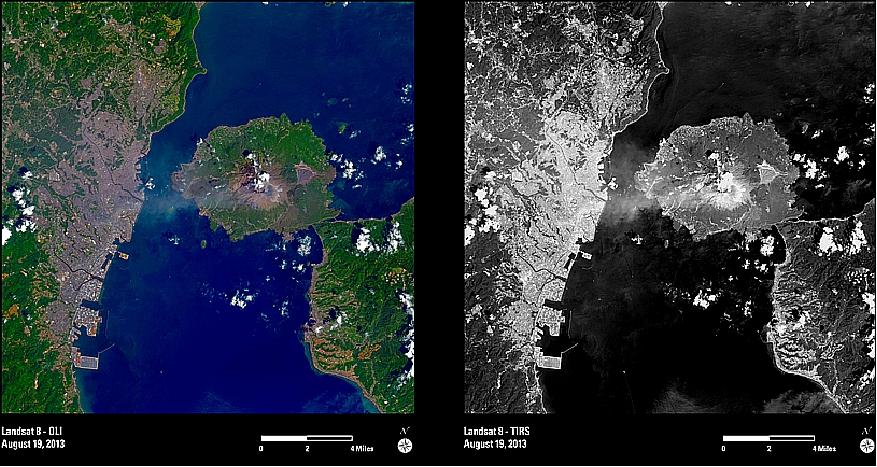

• November 2017: A lot happened on the Antarctic Peninsula under the cloak of the 2017 polar night—most notably, the calving of a massive iceberg from the Larsen C ice shelf. At the time (July), scientists had to rely on thermal imagery and radar data to observe the break and to watch the subsequent motion of the ice. 8) 9)

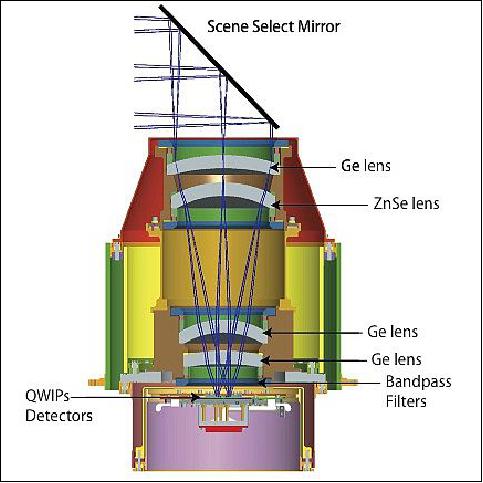

- By August, scientists started getting their first sunlit views of the new iceberg, which the U.S. National Ice Center named A-68. MODIS (Moderate Resolution Imaging Spectroradiometer) on NASA's Terra satellite captured a wide view of the berg on September 11. A few days later, on September 16, the OLI (Operational Land Imager) and TIRS (Thermal Infrared Sensor) on Landsat-8 captured these detailed images.

- The image on the left of Figure 11 shows the icebergs in natural color. The rifts on the main berg and ice shelf stand out, while clouds on the east side cast a shadow on the berg. The thermal image on the right shows the same area in false-color. Note that the clouds over the ice shelf do not show up as well in the thermal image because they are about the same temperature as the shelf. Thermal imagery has the advantage of showing where the colder ice ends and "warm" water of the Weddell Sea begins. It also indicates differences in the thickness of ice types. For example, the mélange is thicker (has a colder signal) than the frazil ice, but thinner (warmer signal) than the shelf and icebergs.

- Both images show a thin layer of frazil ice, which does not offer much resistance as winds, tides, and currents try to move the massive iceberg away from the Larsen C ice shelf. In a few weeks of observations, scientists have seen the passage widen between the main iceberg and the front of the shelf. This slow widening comes after an initial back-and-forth movement in July broke the main berg into two large pieces, which the U.S. National Ice Center named A-68A and A-68B. The collisions also produced a handful of pieces too small to be named.

• November 11, 2017: Ushuaia, Argentina, is many things to the growing number of people who live there: the southernmost city in the world, the gateway to Antarctica, and a gorgeous home along a rocky coast. For NASA, the city's southerly location makes it an ideal place to stage science flights to Antarctica. 10)

- The flights are part of Operation IceBridge, NASA's longest-running mission to map polar ice (now in its ninth year in the Southern Hemisphere). For the first time, flights over the icy continent are being staged from Ushuaia, instead of Punta Arenas, Chile. Read more about this campaign on our blog.

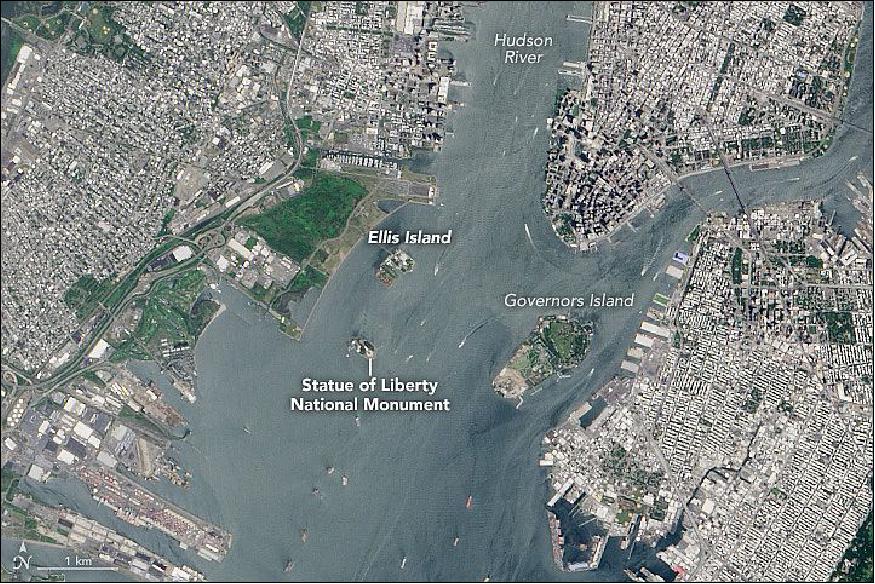

- OLI (Operational Land Imager) on Landsat-8 captured this image of Ushuaia on March 28, 2017. Located at the tip of South America, it is the capital city of Tierra del Fuego province. Port Williams lies across the channel from Ushuaia, but the village is too small to be visible in this natural-color image.

- Ushuaia is located about 250 km southeast of Punta Arenas, Chile. The city's proximity to the Antarctic Peninsula means that NASA's IceBridge campaign scientists gain an hour of extra flight time over science targets. That's important because the P-3 aircraft being flown during this campaign has a shorter range than the DC-8 aircraft flown during previous campaigns. The map of Figure 13 represents how flights from Ushuaia might cross the Southern Ocean to observe the Antarctic Peninsula and its surrounding seas and ice.

- Science flights began on October 29, and the spring weather in Ushuaia has been relatively mild for the first few weeks of the campaign. But as the locals say, you can get four seasons in any given day here. Strong winds, cold temperatures, and heavy rain are not out of the question. Living or visiting here means you should be ready for any kind of weather at all times.

- The extent of the urban area visible in the satellite image shows that, indeed, the city covers a sizeable area for such a remote part of the world (23 km2). Census information from 2010 reported the population in Ushuaia to be 56,956—almost double the population in 1991. Still, that's just a small fraction of the country's total population of more than 40 million people, most of whom live in Buenos Aires province.

- Ushuaia's port is partially used for industry; container ships dock here, and cargo boxes are stacked in tidy, colorful rows along the shore. Tourism is also important: People come from around the world to hike in Tierra del Fuego National Park, ski in the mountains, cruise to see penguins on Martillo Island, or catch a cruise ship to Antarctica.

Improvements to the quality and usability of Landsat satellite data have been made with the release of a new USGS product called Landsat Analysis Ready Data (ARD). This product will help reduce the time needed to process and analyze data and imagery, a significant advantage to scientists studying landscape changes, including changes from wildfires, hurricanes, vegetation cover, drought and other events. A fundamental goal for Landsat ARD is to significantly reduce the amount of data processing for scientists, who currently have to download and prepare large amounts of Landsat scene-based data for time-series investigative analysis. ARD provides users with notable flexibility in how they access customized Landsat data. For example, users will have the ability to tailor requests according to specific needs in terms of geospatial regions, spectral bands and collection dates. Landsat data are the world's longest continuously acquired collection of space-based land remote sensing data. ARD products represent over 30 years of Landsat data available at the highest scientific quality ever produced. This initial ARD release includes Landsat 4-8 imagery of the conterminous United States, Alaska and Hawaii. In the future, the USGS plans to add the earlier Landsat 1-5 Multispectral Scanner era imagery to the ARD product suite and eventually expand ARD to include the full global Landsat archive. ARD will serve many purposes such as the foundational dataset for the recent USGS Land Change Monitoring, Assessment, and Projection (LCMAP) initiative. The initiative aims to characterize historical and near-real time land-cover changes across the United States. The ARD products are based on the recently released Landsat Level-1 Collection structure. Landsat Level-1 products refer to the most basic level of processing that has been applied to a scene for them to be used in applications. This collection management structure ensures access to Landsat Level-1 products as they are acquired and a consistent archive of known data quality. The USGS generates ARD products from data acquired by the Landsat 4-5 Thematic Mapper, Landsat 7 Enhanced Thematic Mapper Plus and Landsat 8 Operational Land Imager and Thermal Infrared Sensor instruments. Landsat ARD is created after processing Landsat Level-1 Collection scenes into Albers Equal Area Conic projection. The USGS processes these products to create top of atmosphere reflectance, brightness temperature and atmospherically corrected surface reflectance. The USGS assembles these products into "tiles" adapted from the Web Enabled Landsat Data tiling scheme. This tiling scheme ensures that each pixel in an ARD tile represents the same location on the Earth's surface through the entire ARD time series record from 1982 to the present. In addition to this higher-level spectral band processing of geophysical parameters, ARD includes several pixel-level quality assessment bands. These bands document the presence of sensor, solar, atmospheric and topographic conditions and traceability to the Landsat Level-1 input source scenes used in ARD. Each ARD tile product is accompanied by comprehensive metadata that ensures full traceability to the Level-1 input source scenes as well as the versions of the algorithms and processing software used to generate them. The USGS has documented ARD product characteristics in the Landsat ARD Data Format Control Book. ARD results from a USGS-NASA decision to make Landsat data more relevant for the next generation of information applications. -Users can access Landsat ARD through the EarthExplorer data portal. |

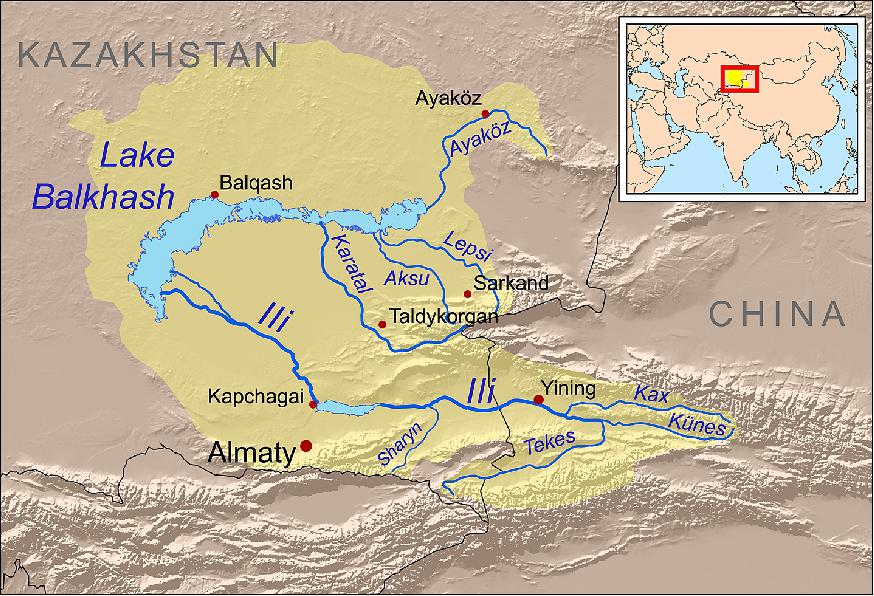

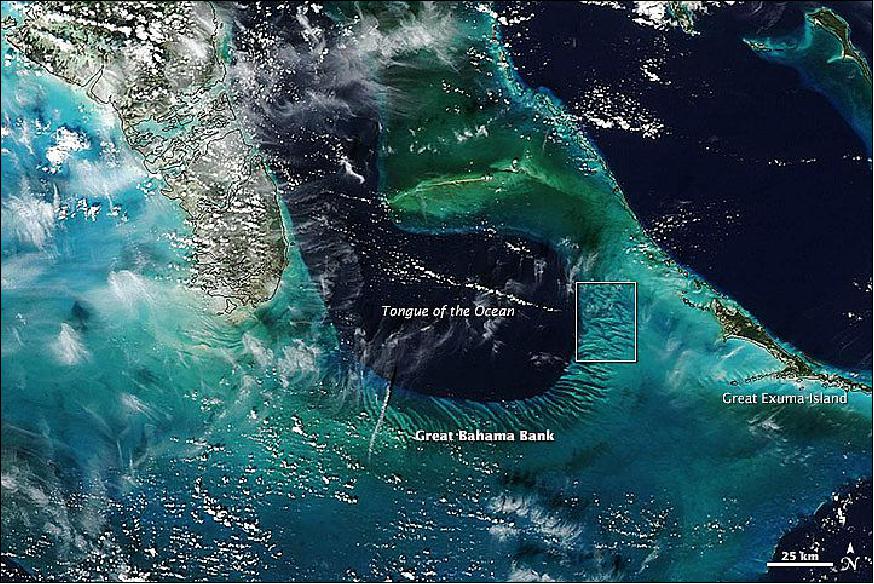

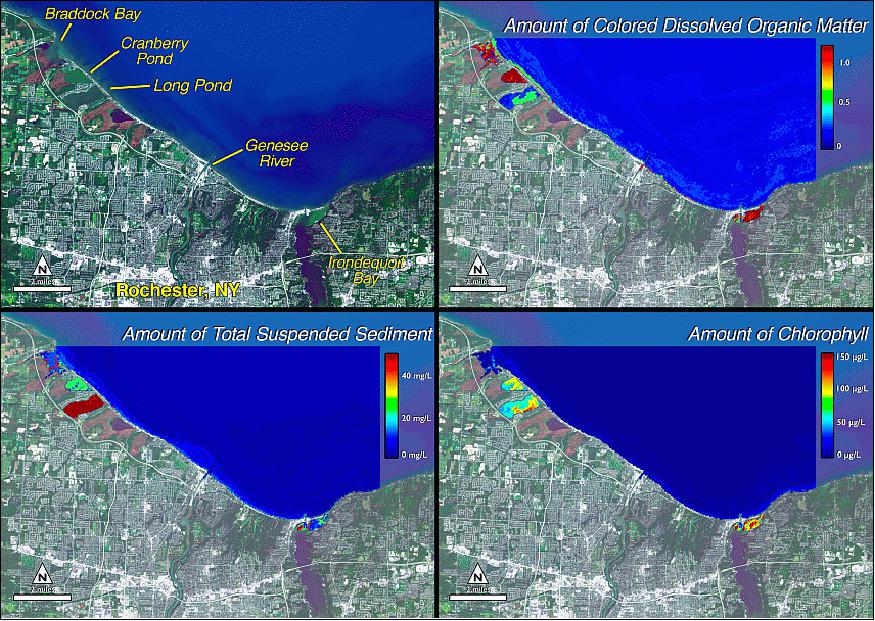

• November 4, 2017: The Aral Sea and Lake Balkhash have a lot in common. Both lakes are located in an arid part of Central Asia; both are somewhat saline; and neither has an outlet. But after the desiccation of the Aral Sea—once the fourth-largest lake in the world—Balkhash now covers a comparatively larger area. Spanning 17,000 km2 in Kazakhstan, Lake Balkhash is the largest lake in Central Asia and fifteenth-largest in the world (Figures 14 and 16). 12)

- Water in the western part of the lake is almost fresh—suitable for drinking and industrial uses—whereas the eastern side of the basin is brackish to salty. The western side is also murkier; visibility/light penetrates to about 1 meter, compared to more than 5 meters on the eastern side. This murkiness, and the water's milky, yellow-green color, is likely due to sediments suspended in the water. "The lake is very shallow, and it is windy nearly every day, so waves can stir up sediments from the bottom," said Niels Thevs of the University of Greifswald (Germany) and the Central Asia office of the World Agroforestry Center.

- Anywhere between 70 to 80 percent of the lake's water comes from the Ili River, which enters the lake along the eastern shoreline. The surrounding delta (green) is now one of the largest wetlands in Central Asia. "I imagine that the wetlands of the Ili Delta look like the wetlands around Aral Sea 50 years ago," Thevs said.

- Thevs describes large parts of the Ili Delta that are only accessible by boat, where you can cruise for hours amid 3-meter-high reeds. These reeds (Pharagmites australis) are considered invasive in the United States. Not so in the Ili Delta, where the plant is an important part of the ecosystem. Thevs also describes parts of the delta where the water is so crystal clear that you can see fish and water plants up to 7 to 8 meters below.

- If you were to cruise in a boat in the main part of the lake, you could count 43 islands with a total area of 66 km2, according to Zhanna Tilekova of Kazakh National Technical University, who has published research on the region's geoecology. However, those numbers can change. Tilekova noted that as water levels decline, new islands form and the area of existing islands grows. In the western part of the lake, Tasaral (north of this image) and Basaral islands are the largest. Ortaaral and Ayakaral islands are also relatively large (Figure 15). Vegetation, likely small brown shrubs (Saxaul), can grow on these islands. The white areas are likely salt pans.

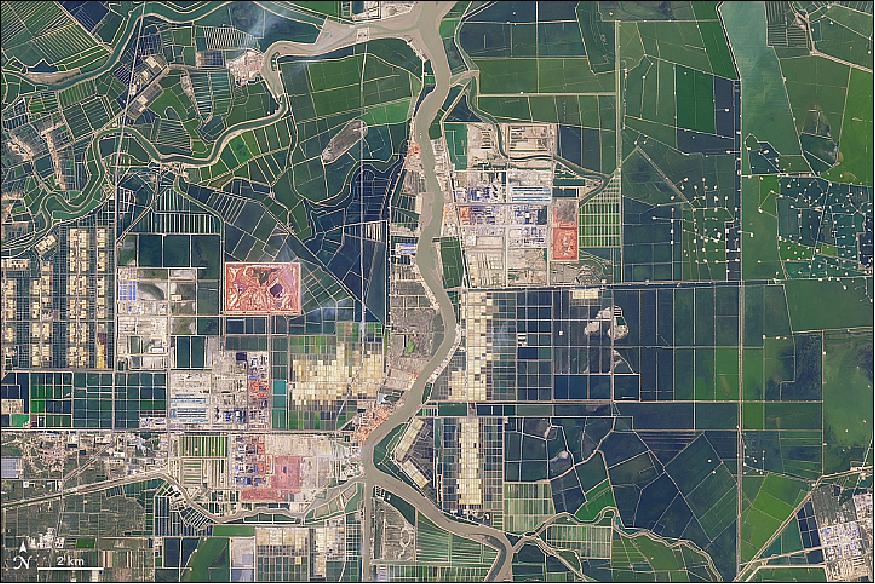

• October 29, 2017: In 1985, this part of Shandong Peninsula in eastern China was an open expanse of tidal mudflats frequented mainly by birds and other wildlife. By 2017, the landscape had been transformed into one that is intensely sculpted by human activity. 14)

- OLI (Operational Land Imager) on Landsat-8 captured this natural-color image on September 8, 2017 (Figure 17). The area falls within Binzhou, a prefecture in northern Shandong Province. Seen from above, the landscape is checkered with squares and rectangles, likely aquaculture ponds and brine pools used to produce salt. Dozens of drill pads for oil pumps are visible on the right side of the image. This area falls within the Shengli oil field, the second largest oil field in China.

- Heavy industry—likely oil-refining facilities—are visible near the center of the image. Landsat imagery shows that construction of these industrial facilities began in 2012. The drill pads were mostly established in the mid-1990s. Other major industrial products produced in Binzhou include garments, a fuel called coke, heavy machinery, and cement.

- In research that uses decades of Landsat imagery to determine where surface water has undergone the most change, this area stands out. Browse the Aqua Monitor and Surface Water Explorer to see how the distribution of surface water has changed in this part of China since the 1980s.

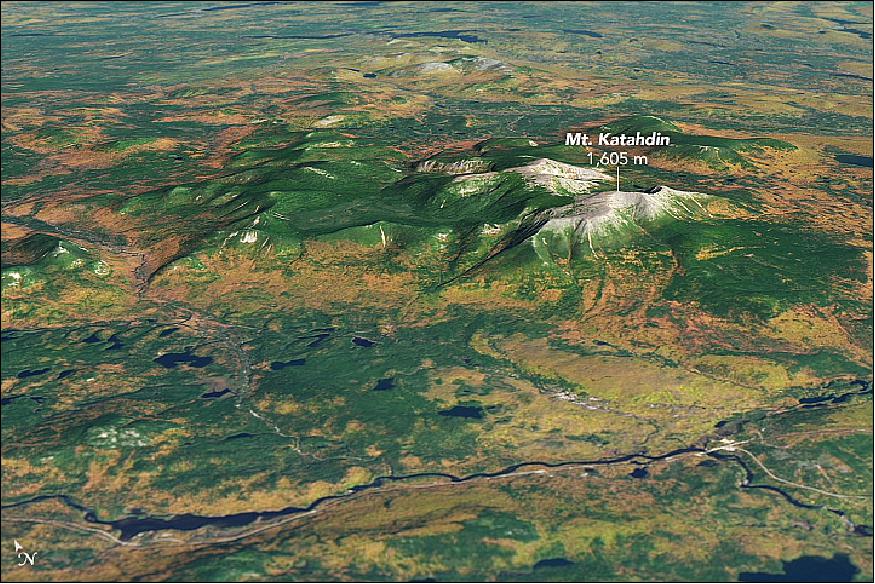

• October 22, 2017: As autumn progresses, so does the trail of color across New England. The reds, yellows, and oranges of the season typically emerge first on the deciduous trees and shrubs at higher latitudes and elevations. That was the case on October 13, 2017, when the Operational Land Imager (OLI) on Landsat-8 captured this natural-color image of foliage in north-central Maine. 15)

- The image of Figure 18 shows the mountainous part of Baxter State Park, an 200,000-acre (809 km2) area of protected wilderness. The summit of Mount Katahdin rises to 1,605 m, the tallest point in the state. Vegetation growth is stunted on the mountain's upper slopes and tablelands, which appear light tan. Moving down from the tree line you start to see evergreens, and then deciduous species with magnificent, colorful foliage. When the image was acquired, leaf color was at its local peak for 2017.

- "Typically, northern Maine reaches peak conditions the last week of September into the first week of October," according to the Maine Foliage Report. "The rest of the state's progression of color will start occurring from north to south in mid-October. Coastal Maine typically reaches peak conditions mid-to-late October."

- Leaf color appears around the same time every year, when daylight grows shorter and triggers plants to slow and stop the production of chlorophyll. But for the best color, leaves need dry weather and cooler temperatures. According to news reports, New England's foliage this year may not be as vibrant as other years. As of early October, many areas had not yet seen temperatures cool off much, causing leaves to go from green to brown.

- The Appalachian National Scenic Trail, generally known as the Appalachian Trail or simply the A.T., is a marked hiking trail in the Eastern United States extending between Springer Mountain in Georgia (Southern terminus) and Mount Katahdin in Maine (Northern Terminus). The trail is about 3500 km in length, claimed to be the longest longest hiking-only trail in the world. More than 2 million people are said to do at least a one day-hike on the popular trail each year. "Thru-hikers" attempt to hike the trail in its entirety in a single season — more than 2,700 people thru-hiked the trail in 2014. 16)

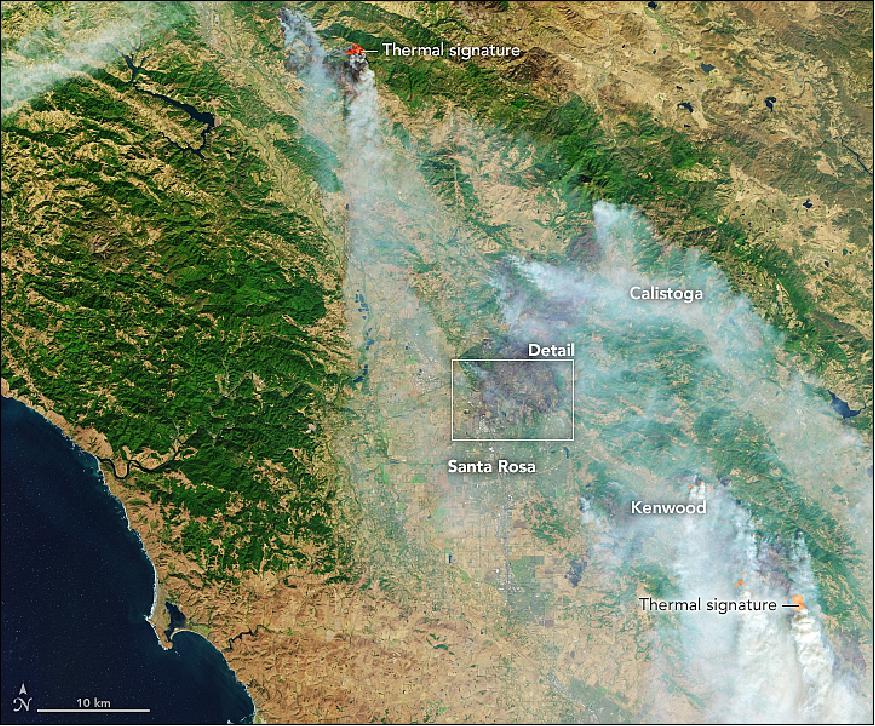

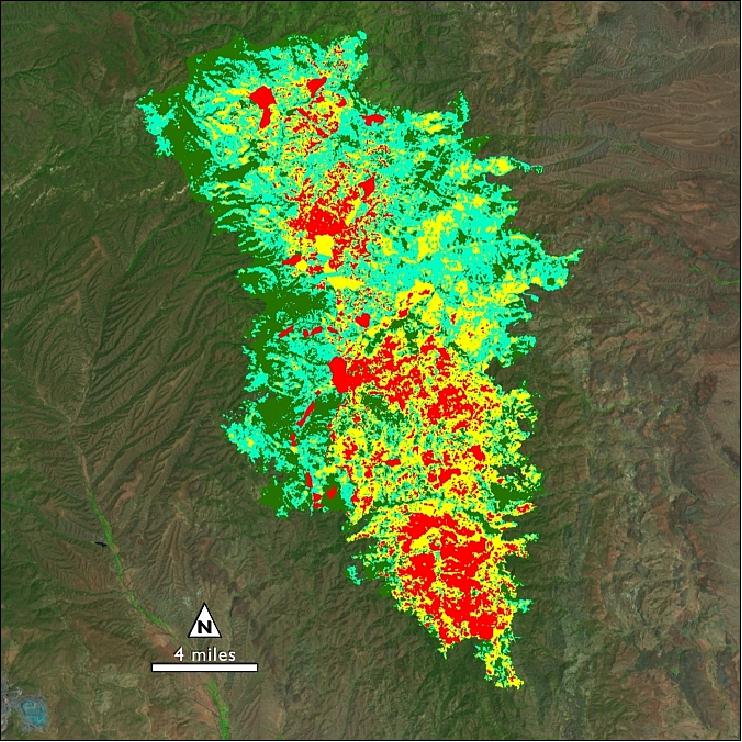

• October 13, 2017: Devastating wildfires have burned through California's wine country since October 8, 2017, taking dozens of lives and leaving thousands of people homeless. Even communities distant from the fires have been plagued by poor air quality, as the smoke plumes have darkened skies and canceled school and other activities across the region. 17)

- On October 11, OLI on Landsat-8 acquired the data for these false-color images of the fires near Santa Rosa and other communities in Northern California. The images are composites combining shortwave infrared, near-infrared, and green (OLI bands 6-5-3) with natural color (bands 4-3-2) and a thermal infrared signature (TIRS, band 10). These combinations make it easier to see through the smoke to the burn scars and the still-active fires.

- In the past week, 21 wildfires have ignited in Napa, Sonoma, Solano, and Mendocino counties and other communities north and east of San Francisco Bay. Fanned by northeasterly Diablo winds, the fires have collectively consumed at least 170,000 acres (265 square miles) of land—an area about half the size of the city of Los Angeles.

- The most prominent events include the Tubbs fire (between Santa Rosa and Calistoga, Figure 20), which has burned more than 34,000 acres; the Atlas fire (near Lake Berryessa, off the lower right of our image), which torched 44,000 acres; and the Redwood/Potter fires (near Mendocino National Forest, north of this scene) with 32,000 acres burned. Part of the Adobe fire (about 8,000 acres) appears in the lower right of the image, near Kenwood.

- CalFire and local officials reported that at least 3,500 homes and businesses have been destroyed, and thousands more are being threatened. Tens of thousands of people have evacuated, and thousands of firefighters have been sent to stop the spreading flames. As of the morning of October 12, most of the fires had little or no containment, according to CalFire bulletins, and "red flag warnings" were still being raised for fire weather with low humidity and high winds.

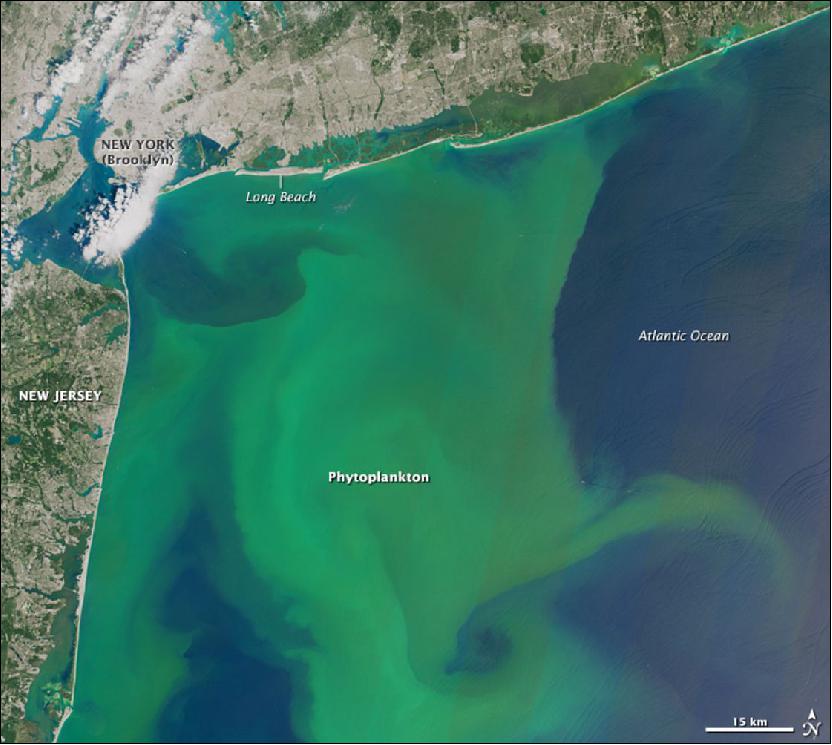

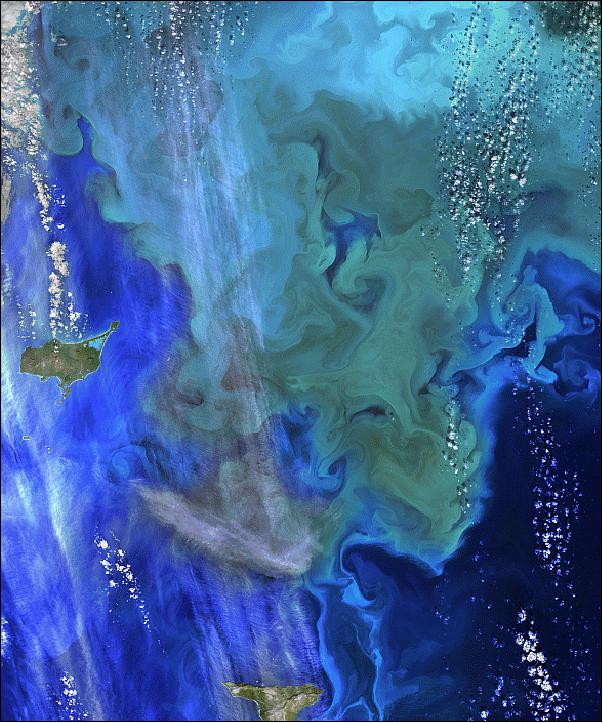

• September 10, 2017: In early September 2017, ocean scientists noticed something swirling in the waters off the coast of the Brazilian state of São Paulo. The sinuous threads of darkness amid the blue Atlantic Ocean were not caused by oil; they were the result of a phytoplankton bloom. 18)

- OLI on Landsat-8 captured the image of Figure 21 on September 5, 2017. Figure 21 is a wide view showing blooms spanning more than 100 km off of São Paulo state. The image of Figure 22 shows details of the bloom near Caraguatatuba. The dark colors are probably high concentrations of dinoflagellates, according to researchers at the University of São Paulo. Analyzing water samples collected from Caraguatatuba Bay and from the channel between the Ilhabela archipelago and the mainland, they identified the species as likely to be Gymnodinium aureolum.

- "But, this is a complicated species to identify," said Aurea Maria Ciotti, a scientist at the university's Center for Marine Biology. She and others are awaiting the results of additional tests to confirm the identification. "Blooms here are very uncommon—this is the first time for this species as far as we know."

- In January 2014, a bloom of a different species—Myrionecta rubra—appeared as dark patches that spanned about 800 km of the waters near Rio de Janeiro. Both the 2014 and 2017 blooms appear dark in satellite images for the same reason; the high concentration of heavily pigmented cells darken the water and less light is reflected directly back toward the satellite.

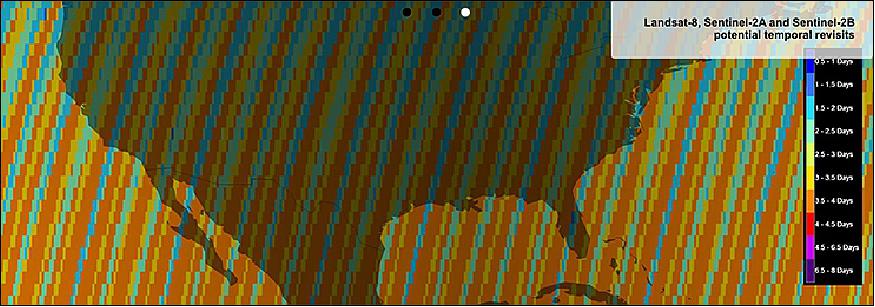

• September 8, 2017: The HLS (Harmonized Landsat Sentinel-2) project has released a new and improved version of its data sets. Landsat-8 and Sentinel-2 satellites have spectral and spatial similarities that make using their data together possible. When the data are used together observations can be more timely and accurate. Note: Sensor co-calibration efforts were underway prior to Sentinel-2A's launch. 19)

- Sentinel-2 and Landsat products represent the most widely accessible medium-to-high spatial resolution multispectral satellite data. Following the recent launch of the first out of two Sentinel-2 satellites, the potential for synergistic use of the two sources creates unprecedented opportunities for timely and accurate observation of Earth status and dynamics. Thus, harmonization of the distributed data products is of paramount importance for the scientific community. Activities to harmonize data products are on their way, yet more coordination is needed to allow the majority of users to easily and effectively include both data types into their work.

- The HLS project is an effort to "harmonize" the data of the two satellite programs so that they can be more easily used in unison. The ultimate goal is to obtain seamless 2-3 day global surface reflectance coverage at 30 meters that removes residual differences between the sensors due to spectral bandpass and view geometry. Currently the v1.3 HLS data set encompasses 82 global test sites that cover about 7% of the global land area.

- Using the processing power of the NASA Earth Exchange (NEX) computer cluster at NASA Ames, the HLS workflow atmospherically corrects data from the satellites, geographically tiles the Landsat data in a manor matching the Sentinel-2 tiling, and then corrects for different sensor view angles BRDF (Bidirectional Reflectance Distribution Function) and does a slight band pass adjustment for the Sentinel-2 data to create the harmonized 30 meter product.

- The new HLS version 1.3 expanded the number of geographic test sites, fixed a bug that was causing incorrectly calibrated coefficients to be used when calculating spectral reflectance and another bug in the BRDF calculation. Version 1.3 also changed the band combination of its quick-look browse images to follow the USGS standard format (SWIR-1, NIR, Red) and it added quality assessments on a per-site basis in addition to the previous per-tile availability.

- Currently, HLS data are only available for dates through April 30, 2017 because the HLS process relies on pre-collection L1T data.

- The next version of HLS will include a wall-to-wall harmonized product for North America, and will migrate to routine weekly processing. The project anticipates releasing the new version (v1.4) by early 2018.

- The HLS team includes researchers from NASA Goddard Space Flight Center, the University of Maryland, and NASA Ames Research Center.

• September 5, 2017: On January 17, 2017, a fire lit by a farmer in a swampy area along the Peruaçu River burned out of control and moved into the Peruaçu Environmental Preservation Area, a national park in the state of Minas Gerais, Brazil. From there, it proceeded to burn amidst grass, bushes, and palm trees (Mauritia flexuosa) for the past eight months. 20)

- Rather than producing big, orange flames and billowing plumes of smoke, this fire smoldered underground in dried out, carbon-rich soil and likely peat. In this part of the world, swampy soils near rivers are often drained to make them more suitable for growing crops. On August 11, 2017, OLI (Operational Land Imager) on Landsat-8 captured this image of the charred landscape (gray) that the fire left behind.

- "The fire spread slowly through soil and roots without any visible flames, but it was able to move up the hollow trunks of the Mauritia flexuosa and jump to the palm tree canopy," explained Jose Eugenio Cortes Figueira, a biologist at the Federal University of Minas Gerais who has been monitoring the fire.

- In mid-August 2017, the burn scar was still smoldering and hundreds of palm trees had toppled over. The photograph of Figure 25, taken by Figueira, shows smoke seeping from the ground with several downed palm trunks behind it. As of mid-August, the fire had burned roughly 600 hectares of palm swamp along the river—in roughly the same area that had burned during a similar fire in 2014.

![Figure 24: The OLI image, acquired on Aug. 11, 2017, shows the burn scar left by a palm swamp fire in Brazil along the Peruaçu River. Rather than producing big, orange flames and billowing plumes of smoke, this fire smoldered underground in dried out, carbon-rich soil and likely peat. The fire spread slowly through soil and roots, but it was able to move up the hollow trunks of palm trees in the area and burn off the canopy [image credit: NASA Earth Observatory, image by Joshua Stevens, using Landsat data from the USGS, Story by Adam Voiland, with information from Jose Eugenio Cortes Figueira (Federal University of Minas Gerais) and Geraldo Wilson Fernandes (Federal University of Minas Gerais)].](/api/cms/documents/163813/4588098/LS82017-2013_Auto67.jpeg)

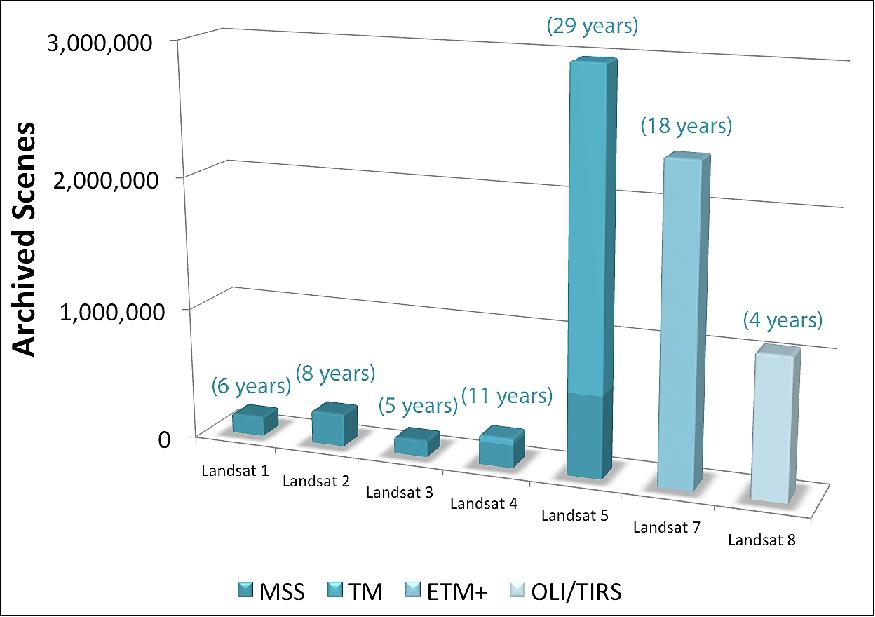

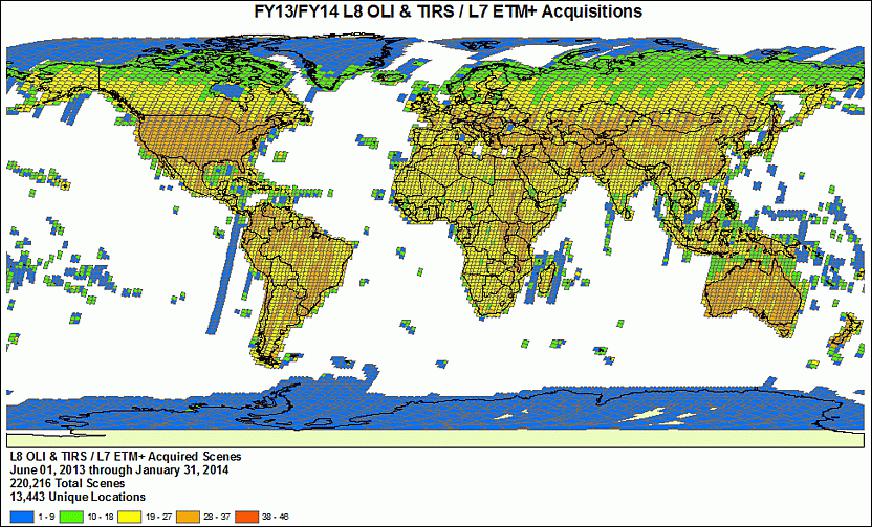

• September 1, 2017: Landsat-8, after collecting data for 4.5 years, has already added over a million images to the archive—this represents 14.8 percent of the entire 45-year Landsat data collection—and each day Landsat-8 adds another ~700 new scenes. 21)

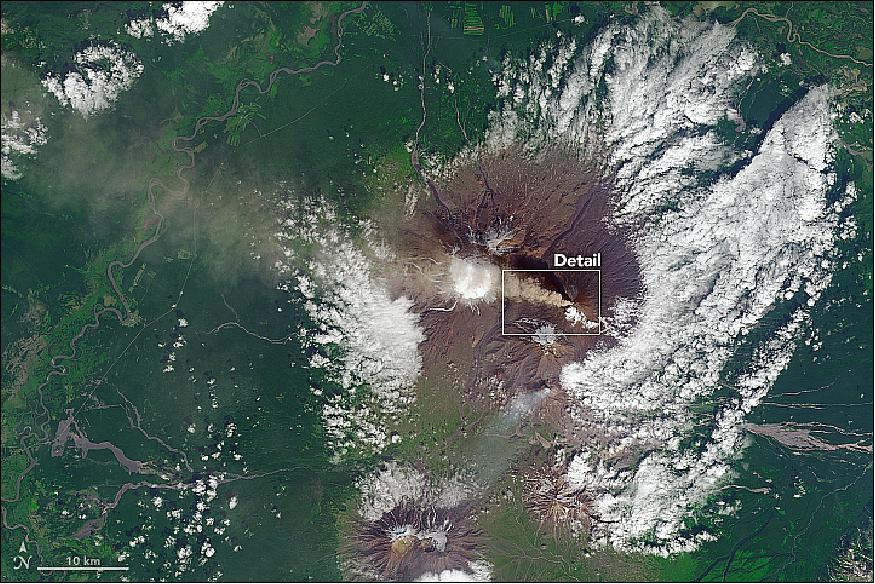

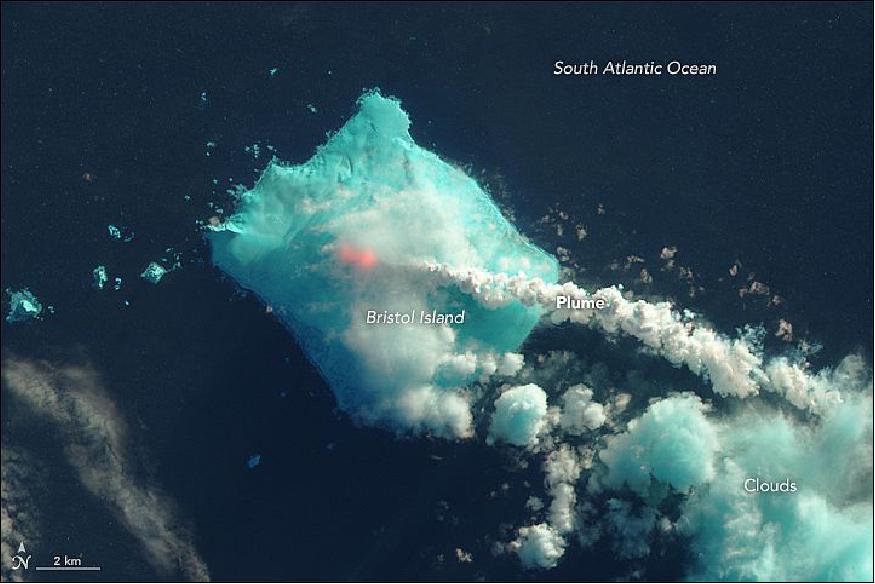

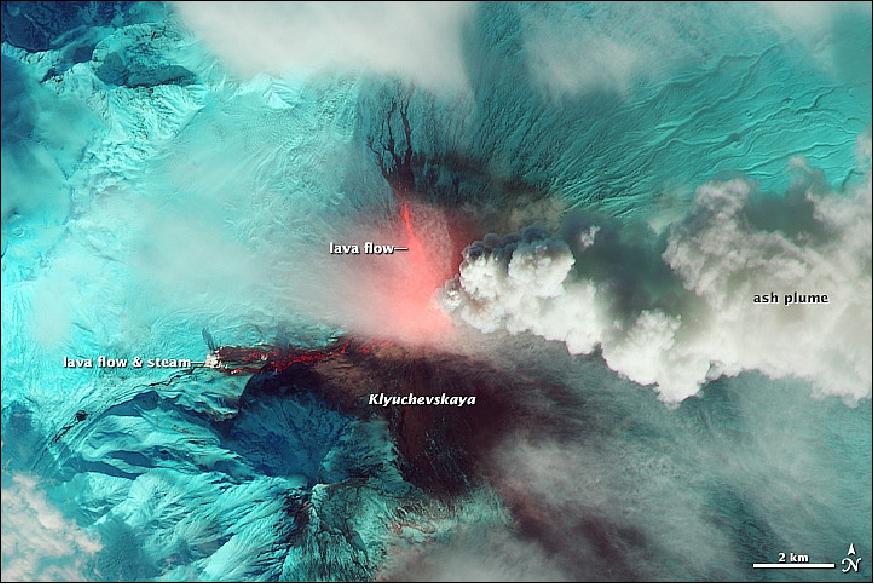

• August 24, 2017: The Kamchatka Peninsula's location along the Pacific Ring of Fire puts the peninsula in one of the most geologically restless areas on the planet. There are more than 100 active volcanoes on the peninsula, one of the highest concentrations of active volcanoes anywhere. 22)

- The most restless of these is Klyuchevskoy (also spelled Kliuchevskoi), a stratovolcano that rises 4,835 meters (15,862 feet) above sea level. According to geological and historical records, Klyuchevskoy has rarely been quiet since it formed about 6,000 years ago. Smithsonian's Global Volcanism Program details a steady stream of activity at Klyuchevskoy punctuated by eruptions every few years that often span months.

- True to form, satellites observed ash and volcanic gases puffing from Klyuchevskoy throughout much of August 2017. The Operational Land Imager (OLI) on Landsat 8 captured this image of a volcanic plume streaming west from the volcano on August 19, 2017. The plume is brown; clouds are white. Note in the broader view that there is also a smaller plume streaming from Bezymianny, a volcano to the south of Klyuchevskoy.

- Fewer than 300 people live within 30 km of Klyuchevskoy, so eruptions do not pose much risk to people on the ground. However, they can represent a hazard to aircraft if ash clouds rise to heights between 8 and 15 km. The ash plume was at a height of roughly 6 km on the day this image was collected, according to the KVERT (Kamchatka Volcanic Eruption Response Team).

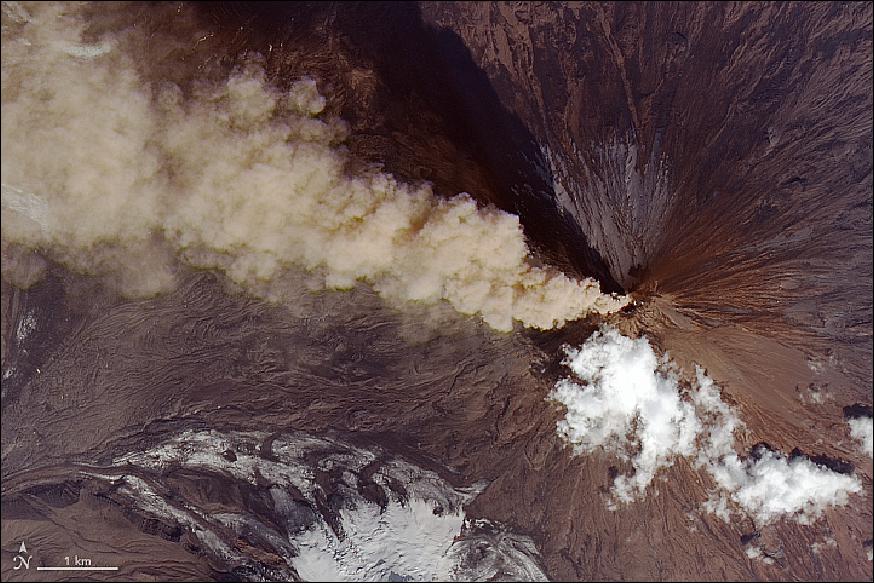

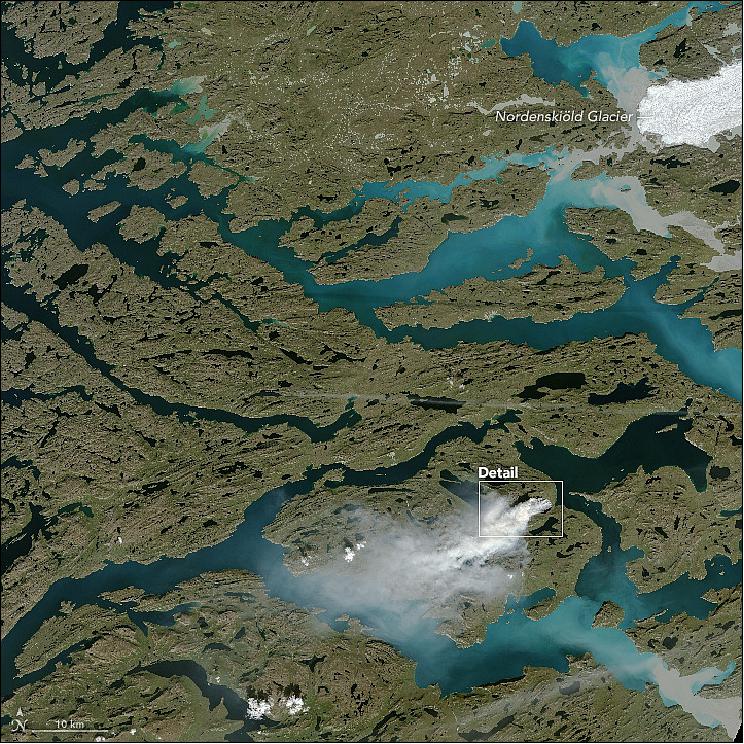

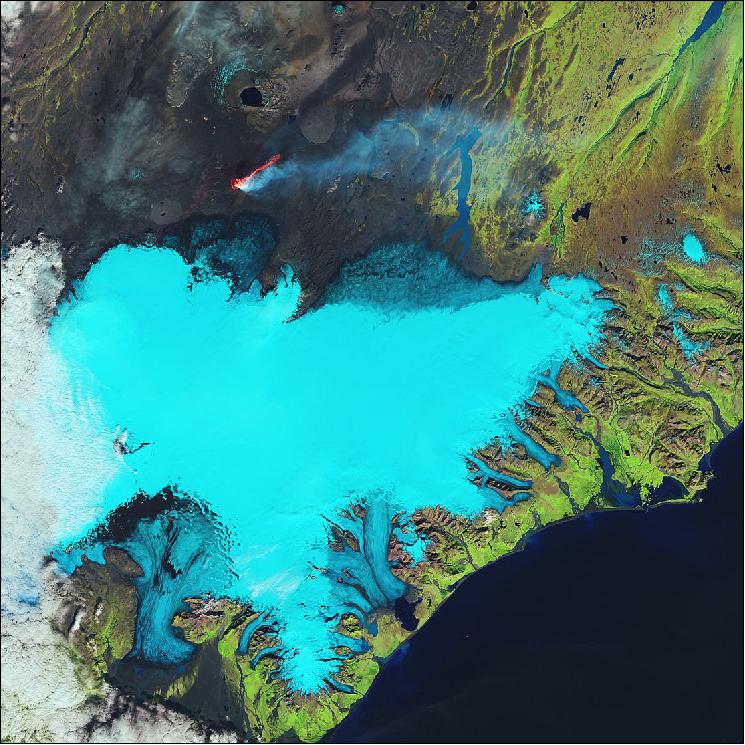

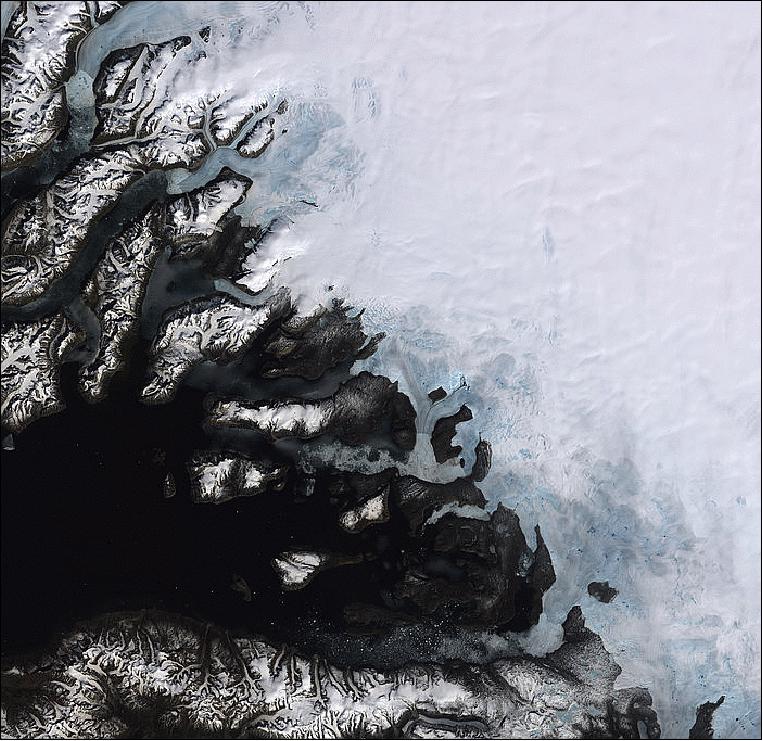

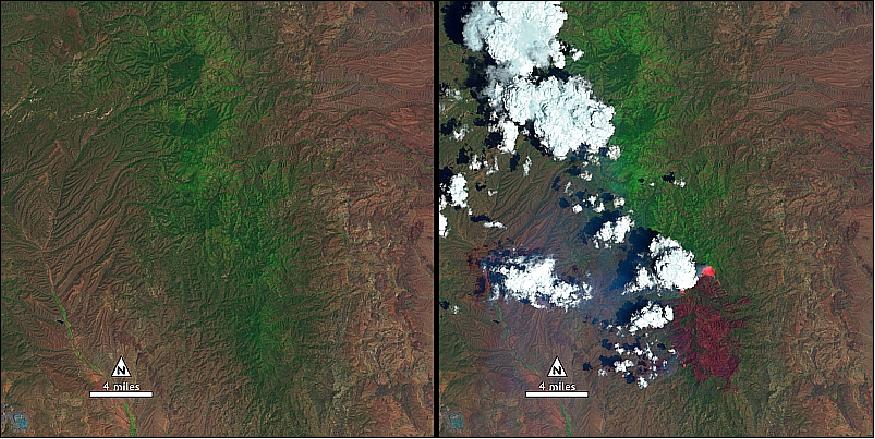

• August 12, 2017: Greenland is best known for its ice, but some remote sensing scientists found themselves closely tracking a sizable wildfire burning along the island's coast in August 2017. The fire burned in western Greenland, about 150 km northeast of Sisimiut. 23)

- Satellites first detected evidence of the fire on July 31, 2017. MODIS (Moderate Resolution Imaging Spectroradiometer) and VIIRS (Visible Infrared Imaging Radiometer Suite) on Suomi NPP collected daily images of smoke streaming from the fire over the next week. OLI (Operational Land Imager) on Landsat-8 captured these more detailed images (Figures 29 and 30) of the fire on August 3, 2017.

- While it is not unprecedented for satellites to observe fire activity in Greenland, a preliminary analysis by Stef Lhermitte of Delft University of Technology in the Netherlands suggests that MODIS has detected far more fire activity in Greenland in 2017 than it did during any other year since the sensor began collecting data in 2000.

- Fires detected in Greenland by MODIS are usually small, most likely campfires lit by hunters or backpackers. But Landsat did capture imagery of another sizable fire in August 2015. According to Ruth Mottram of the Danish Meteorological Institute (DMI), neither DMI nor other scientific groups maintain detailed records of fire activity in Greenland, but many meteorologists at the institute have heard anecdotal reports of fires.

- The blaze appears to be burning through peat, noted Miami University scientist Jessica McCarty. That would mean the fire likely produced a sharp increase in wildfire-caused carbon dioxide emissions in Greenland for 2017, noted atmospheric scientist Mark Parrington of the European Commission's Copernicus program.

- It is not clear what triggered this fire, though a lack of documented lightning prior to its ignition suggests the fire was probably triggered by human activity. The area is regularly used by reindeer hunters, and is not too far from a town with a population of 5,500 people.

- The summer has been quite dry. Sisimiut saw almost no rain in June and half of the usual amount in July. That may have parched dwarf willows, shrubs, grasses, mosses, and other vegetation that commonly live in Greenland's coastal areas and made them more likely to burn.

- Fires emit a soot-like material called black carbon. It is likely that winds will transport some of this material east to the ice sheet where it will contribute to a line of darkened snow and ice along the western edge of Greenland's ice sheet. This area is of interest to climate scientists because darkened snow and ice tends to melt more rapidly than when it is clean.

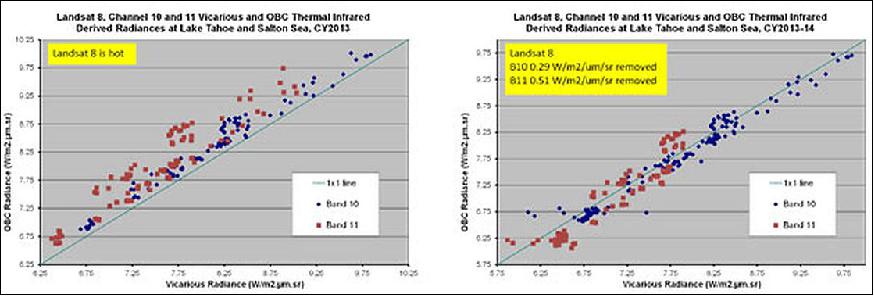

• July 2017: The Landsat-8 OLI instrument continues to be remarkably stable over its four years on orbit. Significant change is only apparent in the Coastal Aerosol band (band 1) and this approximately 1% change in response is currently being corrected in operational data processing. 24)

- In addition, all the on-board calibration devices are working well, and with the exception of a few small (<1%) degradations in the devices used most frequently, have not degraded. The availability of the multiple devices allows identifying the degrading devices and deciphering instrument change from calibrator change.

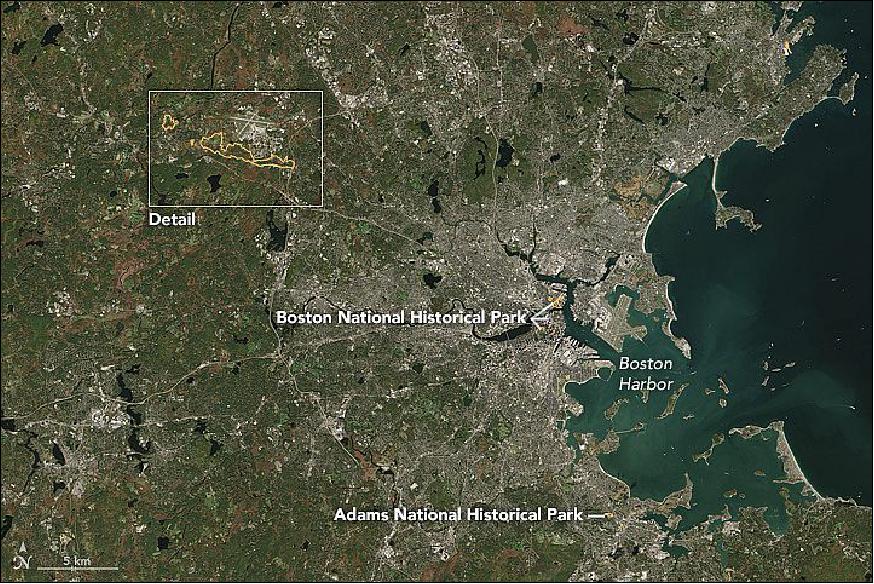

• On July 23, 2017, the Landsat Program celebrateed forty-five years of continuous Earth observation. NASA — working in cooperation with the U.S. Department of the Interior (DOI) and its science agency, the USGS — launched the first Landsat satellite (originally named Earth Resources Technology Satellite 1) on July 23, 1972. 25)

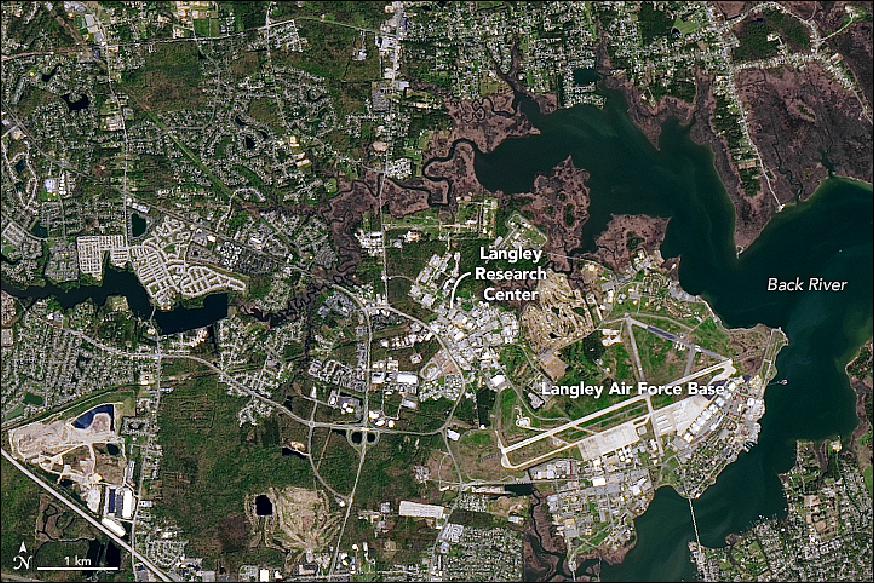

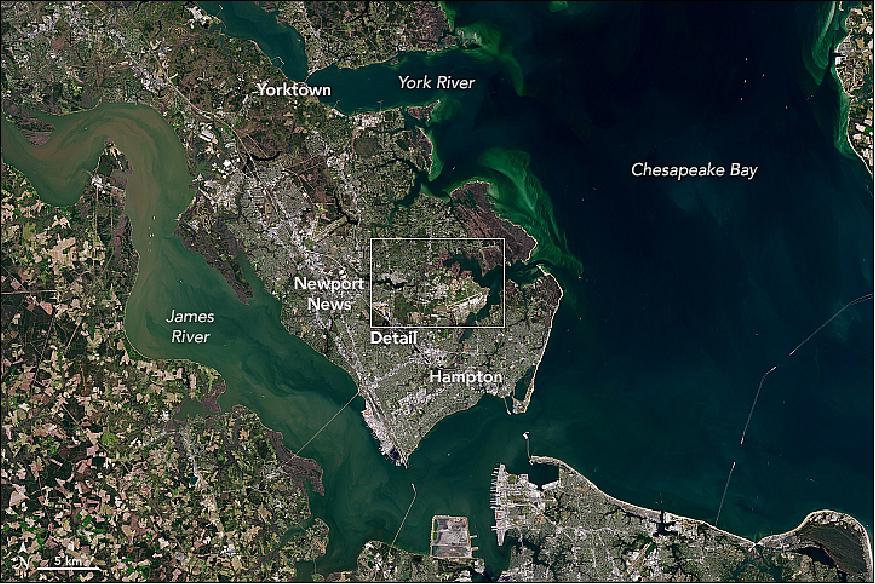

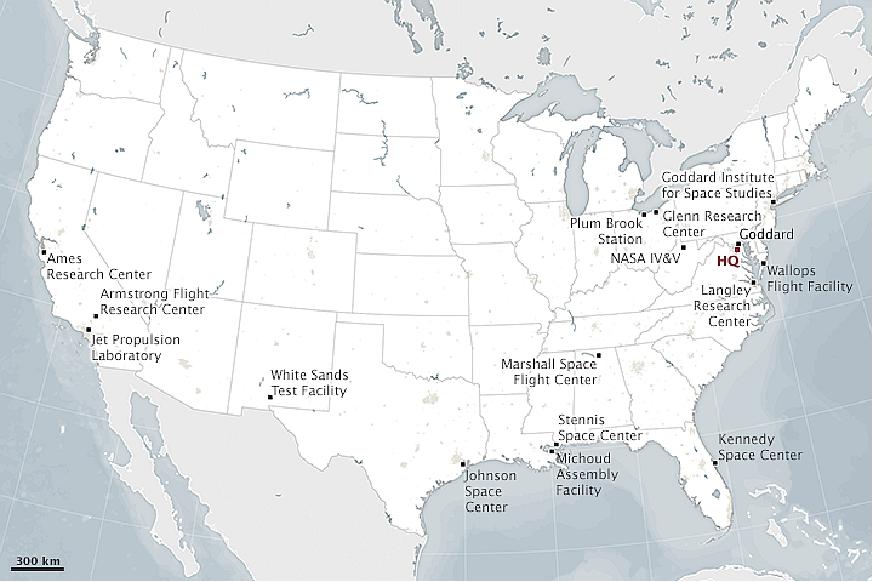

• July 18, 2017: Something happened 100 years ago that changed forever the way we fly. And then the way we explore space. And then how we study our planet. That something was the establishment of what is now known as NASA Langley Research Center (LRC), which is commemorating its 100th anniversary in 2017. 26)

- Just three months after the United States entered into World War I, Langley Memorial Aeronautical Laboratory was carved out of coastal farmland near Hampton, Virginia, as the nation's first civilian facility focused on aeronautical research. The goal was, simply, to "solve the fundamental problems of flight." Under the direction of the National Advisory Committee for Aeronautics (NACA), ground was broken for the center on July 17, 1917.

- From the beginning, Langley engineers devised technologies for safer, higher, farther, and faster air travel. More than 40 state-of-the-art wind tunnels and supporting infrastructure have been built over the years, and researchers use those facilities to develop many of the wing shapes still used today in airplane design. Better propellers, engine cowlings, all-metal airplanes, new kinds of rotorcraft and helicopters, faster-than-sound flight—these were among Langley's many groundbreaking aeronautical advances.

- During World War II, Langley tested planes like the P-51 Mustang in the nation's first wind tunnel built for full-sized aircraft. Langley later partnered with the military on the Bell X-1, an experimental aircraft that would fly faster than the speed of sound. Follow-on research would extend the reach of American aeronautics into supersonics and hypersonics. By 1958, NACA would become NASA, and Langley's accomplishments would soar from air into space.

- Over the past half century, LRC has contributed significantly to the development of rockets and to the spacecraft testing and astronaut training of the Mercury, Gemini, and Apollo programs. In particular, astronauts practiced Moon landings here with the lunar lander. Langley also led the unmanned Lunar Orbiter initiative, which not only mapped the Moon, but helped choose the spot for the first human landing. With the Viking 1 landing in 1976, Langley led the first successful U.S. mission to the surface of Mars. All along, the center and its researchers have contributed to the study of Earth via satellite and through instruments flown on the space shuttles, space station, and NASA aircraft.

- Over the past half century, LRC has contributed significantly to the development of rockets and to the spacecraft testing and astronaut training of the Mercury, Gemini, and Apollo programs. In particular, astronauts practiced Moon landings here with the lunar lander. Langley also led the unmanned Lunar Orbiter initiative, which not only mapped the Moon, but helped choose the spot for the first human landing. With the Viking 1 landing in 1976, Langley led the first successful U.S. mission to the surface of Mars. All along, the center and its researchers have contributed to the study of Earth via satellite and through instruments flown on the space shuttles, space station, and NASA aircraft.

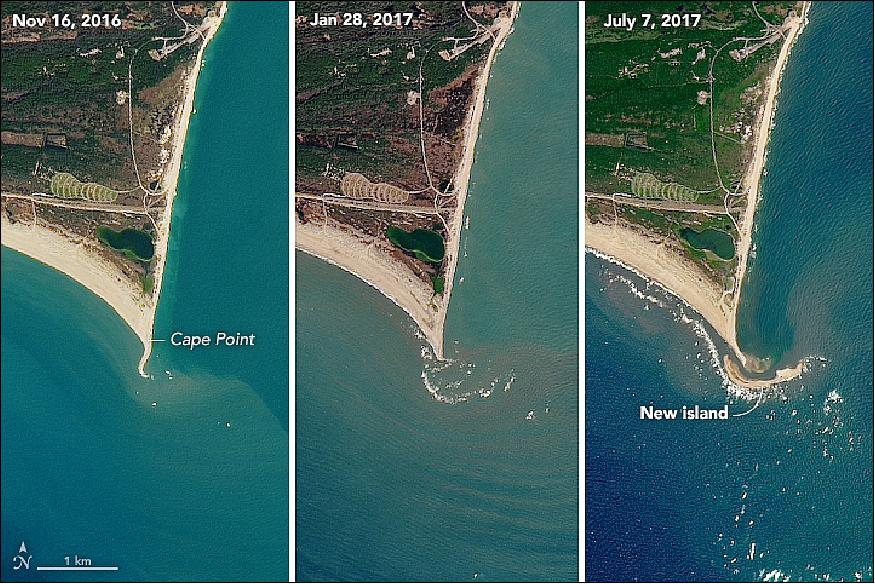

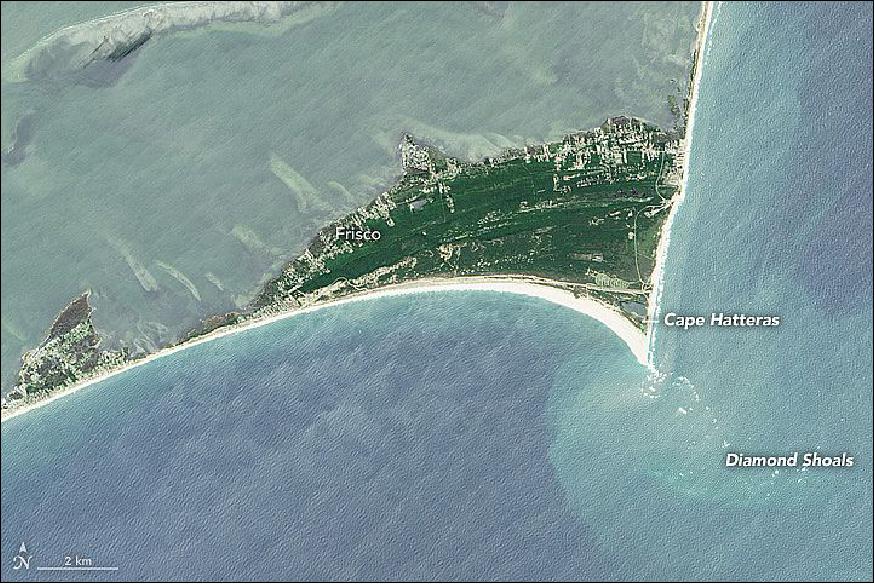

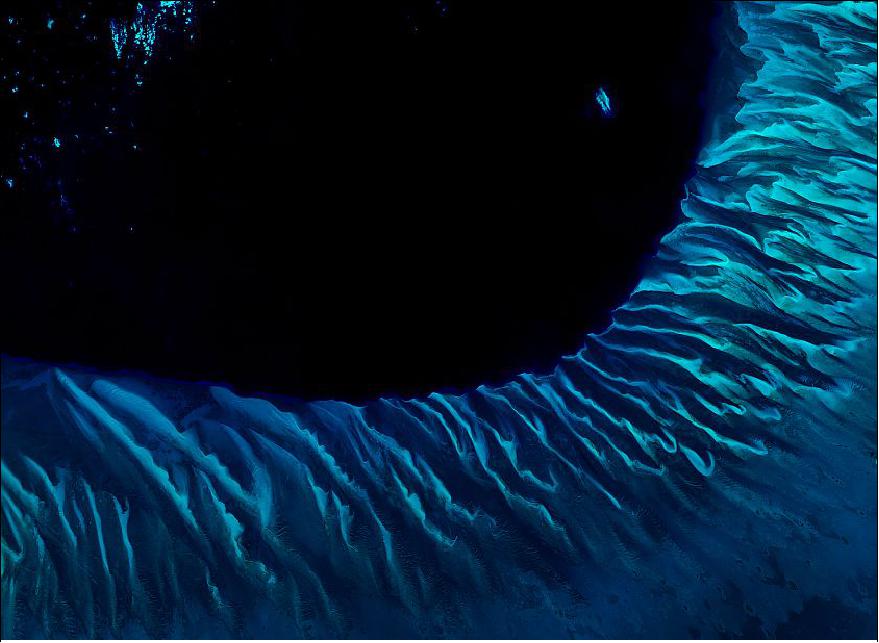

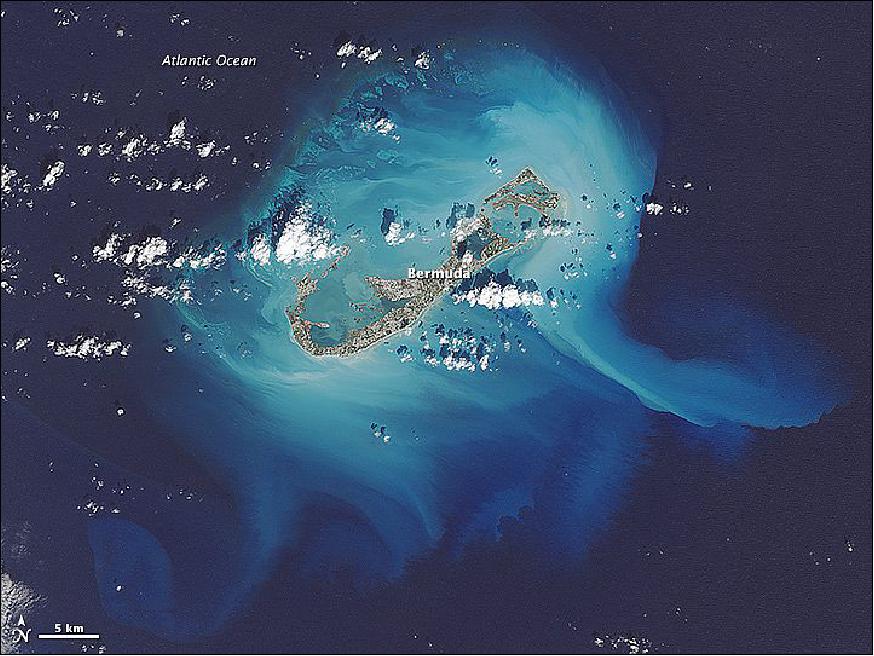

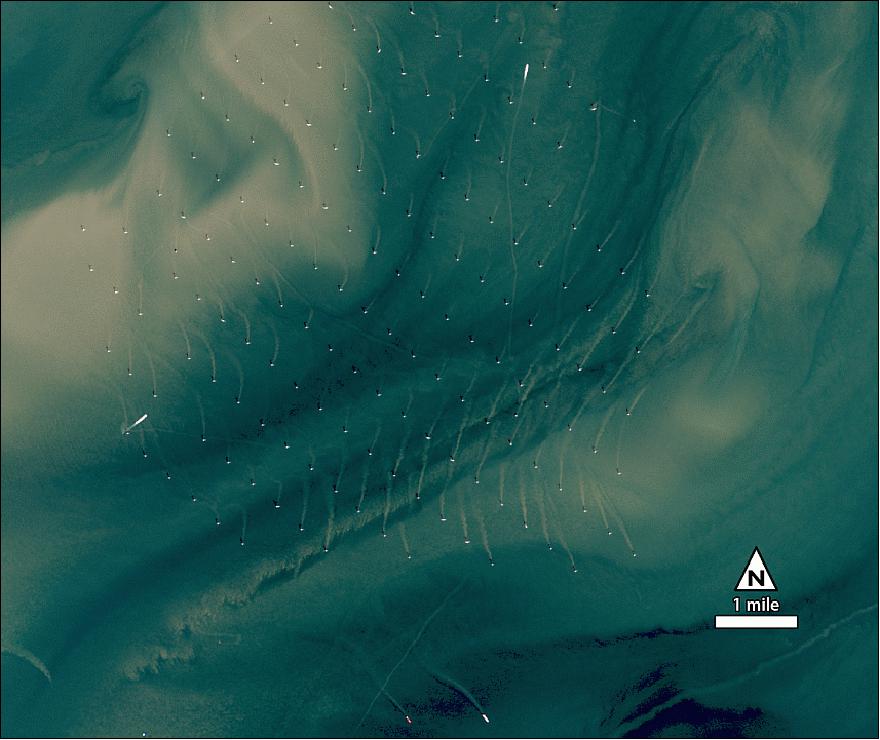

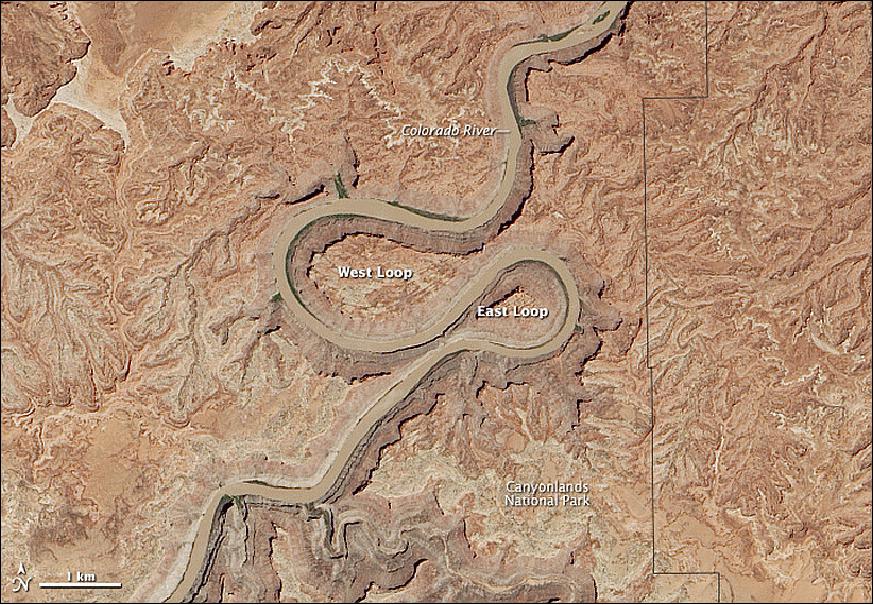

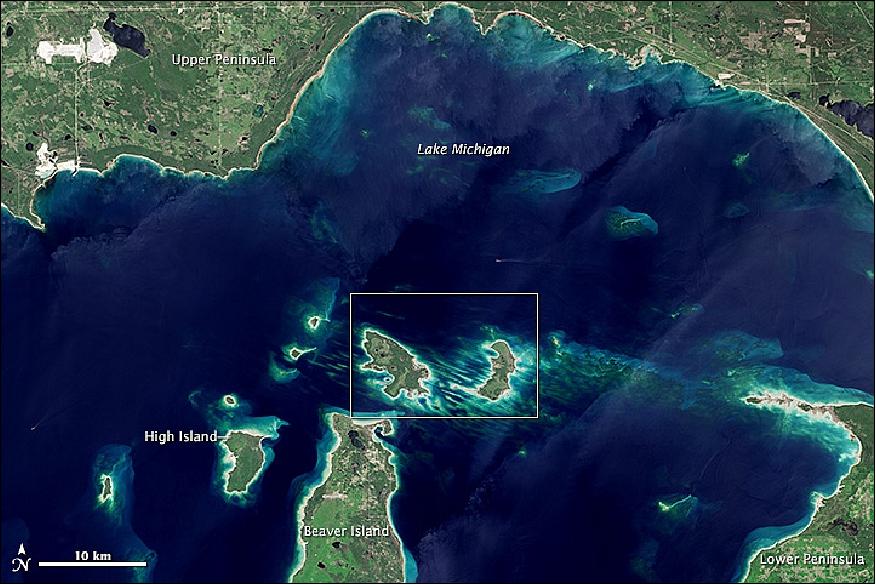

• July 12, 2017: The waters off of North Carolina's barrier islands have been called a "graveyard of the Atlantic." Countless ships have wrecked here, due to the area's treacherous weather and currents and its expansive shoals. These shoals are, by definition, usually submerged. But occasionally parts of them can rise above sea level. 27)

- These natural-color images, acquired by OLI (Operational Land Imager) on the Landsat-8 satellite, show the shoal area off of Cape Point at Cape Hatteras National Seashore—the site of a newly exposed shoal nicknamed "Shelly Island." The first image was captured in November 2016. When the second image was acquired in January 2017, waves were clearly breaking on the shallow region off the cape's tip. The site of those breakers is where the island eventually formed, visible in the third image captured in July 2017. The new island measures about a mile long, according to news reports.

- "What exactly causes a shallow region to become exposed is a deep question, and one that is difficult to speculate on without exact observations," said Andrew Ashton, a geomorphologist at the Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution. "A likely process would be a high tide or storm-driven water elevation that piled up sediment to near the surface, and then water levels went down exposing the shoal. Waves then continue to build the feature while also moving it about."

- While the exact mechanism for the formation of Shelly Island this year is mostly unknown, the phenomenon is not uncommon. Cape Lookout, the next cape down the barrier islands (to the southwest, beyond this image) has had several islands form on its shoal over the past decade or two.

- The shoreline and cape tips along North Carolina's barrier islands are constantly in motion. Cape tips are sculpted by waves and currents that hit from all directions. Meanwhile, sediment is carried up and down the coastline and often deposited near the cape tips. Each cape has a so-called "cape-associated shoal" lurking underwater. These submerged mounds of sand can extend for tens of kilometers. They are also very shallow, rising to anywhere from 10 meters to a few meters below the surface in places.

- "Tidal flows moving up and down the coast are diverted by the capes and result in a net offshore current at cape tips and deposition at the shoals," Ashton said. "Occasionally, a portion of the shoal becomes exposed and forms an island."

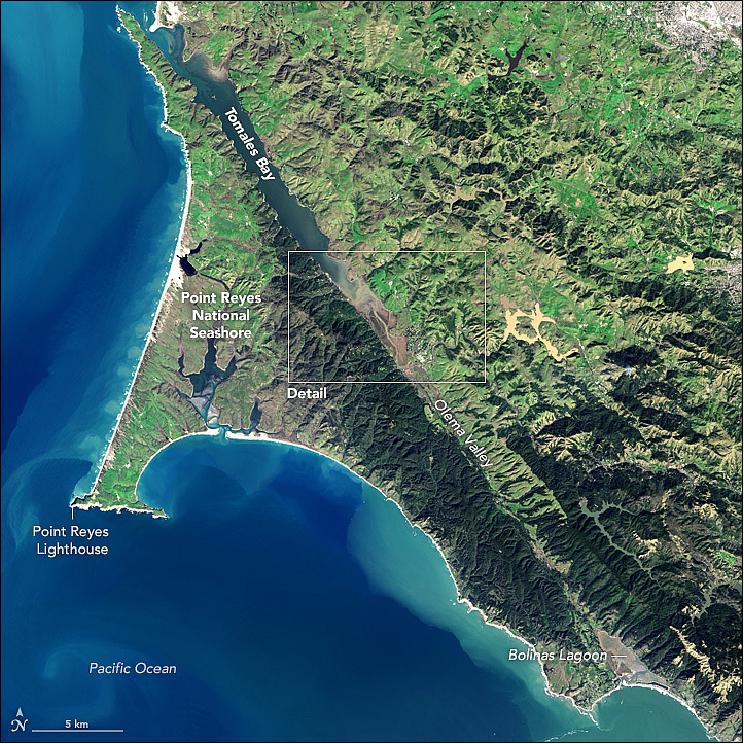

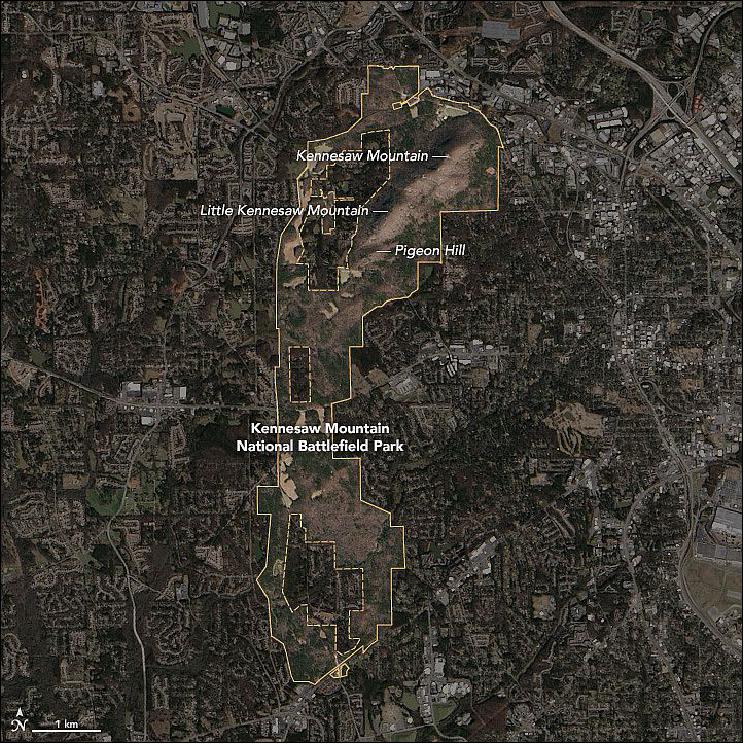

• June 17, 2017: There is an obvious difference between the dark green coniferous forests that dominate the western shore of Tomales Bay and the lighter green grasslands on the east side (Figure 35). But the differences between the two shores run much deeper than the vegetation. - Tomales Bay lies about 50 km northwest of San Francisco, along the edges of two tectonic plates that are grinding past each other. The boundary between them is the San Andreas Fault, the famous rift that partitions California for hundreds of miles. 28)

- To the west of the Bay is the Pacific plate; to the east is the North American plate. The rock on the western shore of the Bay is granite, an igneous rock that formed underground when molten material slowly cooled over time. On the opposite shore, the land is a mix of several types of marine sedimentary rocks. In Assembling California, John McPhee calls that side "a boneyard of exotica," a mixture of rock of "such widespread provenance that it is quite literally a collection from the entire Pacific basin, or even half of the surface of the planet."

- As the plates shift, the ground west of the San Andreas Fault moves northward. On average, movement along the fault averages about 3 to 5 cm per year—about the speed that fingernails grow. However, that movement is anything but steady. The two plates tend to lock together until extreme amounts of pressure build up. When the pressure reaches a breaking point, an earthquake sends the plates lurching. During the Great 1906 San Francisco Earthquake, a road at the head of Tomales Bay was offset by nearly 6 meters.

- In Figure 36, you can see that the direction of the fault follows the orientation of Tomales Bay, running from the head of the Bay through Olema Valley toward Bolinas Lagoon.

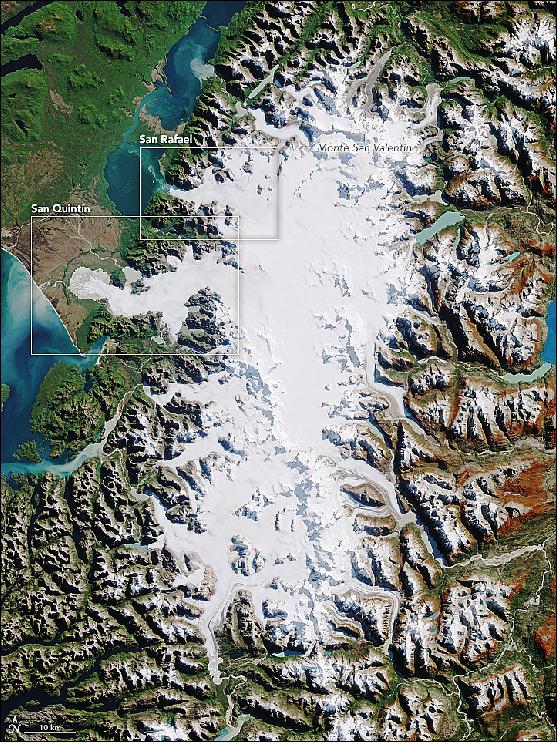

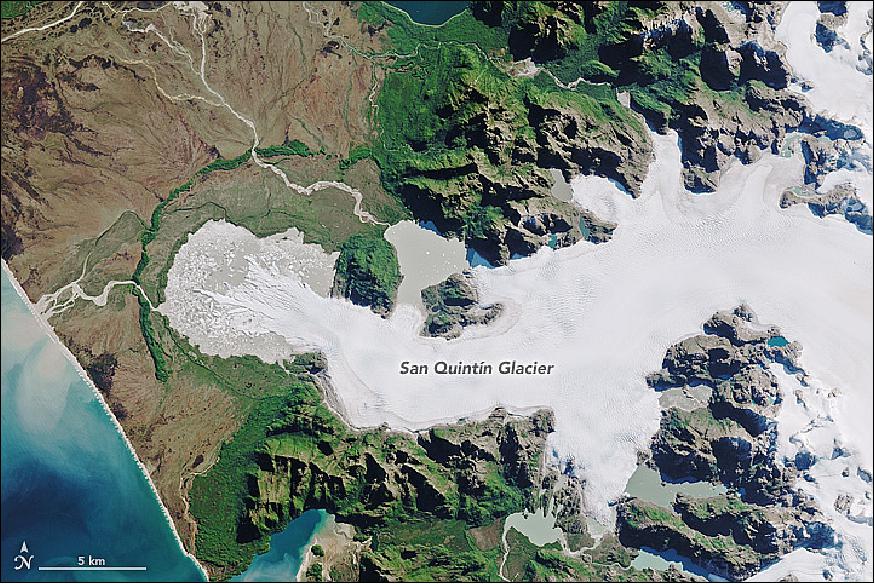

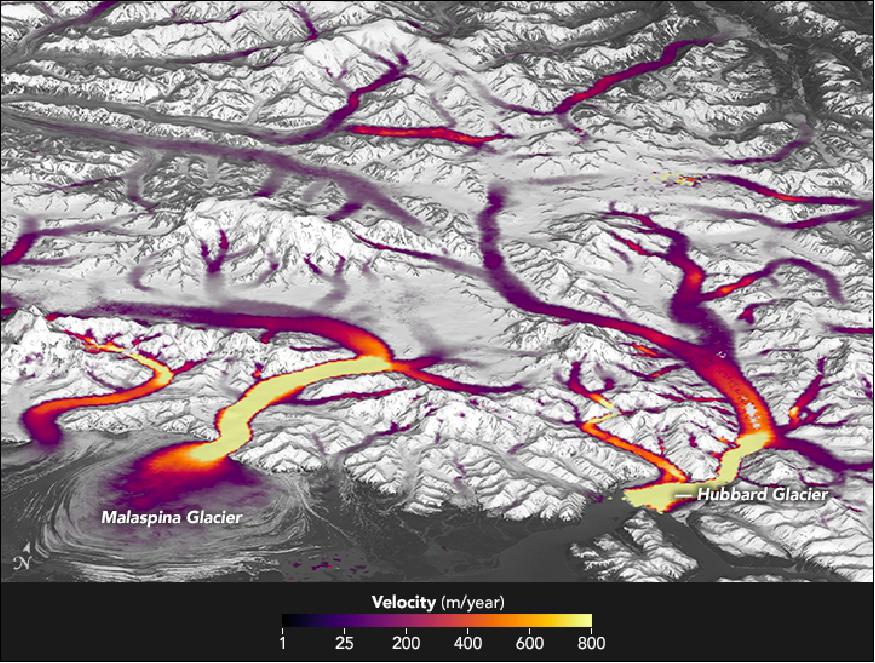

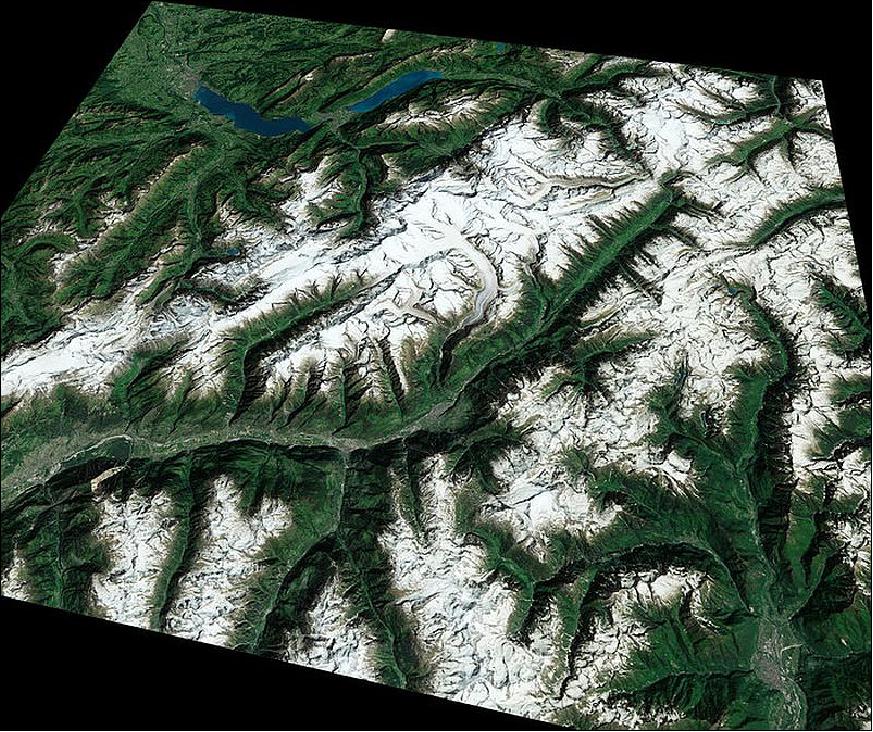

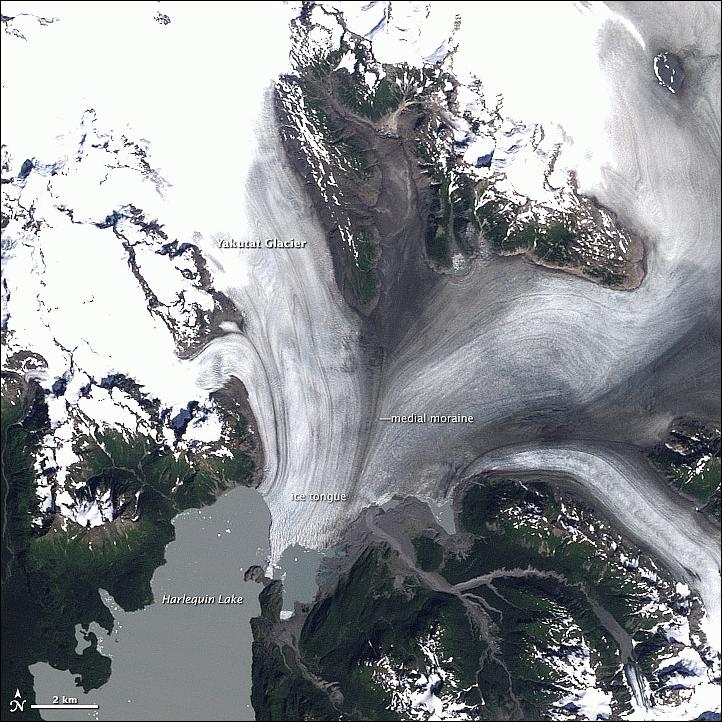

• June 7, 2017: Forests, grasslands, deserts, and mountains are all part of the Patagonian landscape that spans more than a million km 2 of South America. Toward the western side, expanses of dense, compacted ice stretch for hundreds of kilometers of the Andes mountain range in Chile and Argentina. Glaciologist Eric Rignot described these icefields as "one of the most beautiful places on the planet." Their beauty is also apparent from space. 29)

- The two lobes of the Patagonian icefields—north and south—are what's left of a much more expansive ice sheet that reached its maximum size about 18,000 years ago. The modern icefields are just a fraction of their previous size, though they remain the southern hemisphere's largest expanse of ice outside of Antarctica.

- "The rapid thinning of the icefield's glaciers illustrates the global impact of climate warming," said Rignot, of NASA's Jet Propulsion Laboratory and the University of California-Irvine. "We have shown that Patagonia glaciers experience some of the world's most dramatic thinning per unit area, more than Alaska or Iceland or Svalbard or Greenland."

- The northern remnant is the smaller of the two icefields, covering about 4,000 km2 (about a quarter the size of the southern icefield). On April 16, 2017, the Operational Land Imager (OLI) on Landsat 8 captured this rare cloud-free image of the entire North Patagonian Icefield (Figure 37).

- While the northern icefield is smaller than its southern counterpart, it still has 30 significant glaciers along its perimeter. Ice creeps downslope through mountain valleys and exits the through so-called "outlet glaciers." Many come to an abrupt end on land, while others terminate in water. The water-terminating glaciers San Rafael and San Quintín are the icefield's largest.

- The San Rafael Glacier starts near the western flank of Monte San Valentin—the tallest summit in Patagonia—and drains westward into Laguna San Rafael. The lagoon is ringed by a ridge of debris, called a moraine, shoveled into place by the glacier in the past when it was much larger. Visitors to the area in the late 1800s described the glacier as having a large bulbous front, called a piedmont lobe, that spread out well into the lagoon. Since then, the glacier has receded and is no longer lobe-like, though it still actively sheds icebergs from its front in a process known as calving. San Rafael is one of the most actively calving glaciers in the world.

- Part of the reason why this glacier sheds so many bergs is because of its speed. "Flowing" at a speed of 7.6 km/year, San Rafael is the fastest-moving glacier in Patagonia and among the fastest in the world.

- It is also the icefield's only glacier to come into contact with ocean water. Seawater from the Pacific enters the lagoon through the Golfo Elefantes, which connects to the lagoon via the Rio Tempanos (Iceberg River). At 46.7 degrees south latitude, San Rafael is the closest glacier to the equator in the world to connect to the sea.

- There was a point when seawater did not reach the glacier. "It used to be a lagoon with fresh water," said Rignot. "Then an earthquake in the 1960s lowered the ground and connected the lagoon with the ocean waters (the passage for seawater is only a few meters deep)."

- San Rafael's "twin" is the San Quintín glacier immediately to the southwest. This glacier currently ends in a piedmont lobe, and illustrates what San Rafael looked like before it receded. Until 1991, the glacier terminated on land, but with the glacier's retreat, the basin has filled in with water to form a proglacial lake. (Note that the lake water is barely distinguishable from the ice due to its milky color).

- San Quintín does not flow as fast (1.1 km/ year) or calve as many bergs as San Rafael, but it is an impressive glacier on its own, standing as the second-largest in the North Patagonian Icefield. Together with San Rafael, the glaciers drain 37 percent of the icefield.

- Like its twin, San Quintín has been receding dramatically. Researchers have shown that between 1870 and 2011, the glacier lost 14.6 percent of its area. For comparison, San Rafael lost 11.5 percent during the same period.

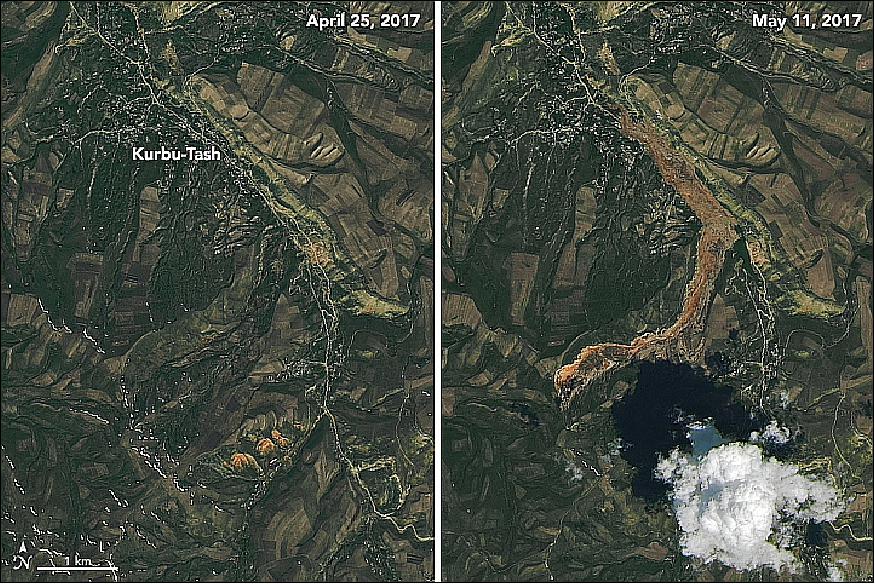

• May 30, 2017: In April 2017, a hillside saturated by melting snow and rainfall collapsed near the village of Kurbu-Tash in southern Kyrgyzstan. Over the following weeks, a slow-moving river of fine-grained soil flowed down a valley and engulfed dozens of homes. 30)

- On May 11, 2017, the OLI (Operational Land Imager) on the Landsat-8 satellite captured an image (right) of the landslide deposit. Freshly exposed soil is tan. For comparison, the image on the left shows the same area on April 25, 2017. The landslide transported 2.8 million m3 of soil, according to Kyrgyzstan's Ministry of Emergency Situations.

- People living in the foothills of the Tien Shan mountains in southern Kyrgyzstan face an unusually high risk of landslides. Several factors contribute to the elevated risk, including the presence of active faults, steep terrain, and the presence of landslide-prone soil types. Loess, for instance, is involved in many landslides in this region because the fine-grained soil becomes quite unstable when saturated with water. Heavy bouts of rain, the melting of snow, and small earthquakes often trigger slides. The risk is particularly high in the spring, when heavy rainfall is most likely. Since the area is densely populated, landslides take lives and destroy many homes each year.

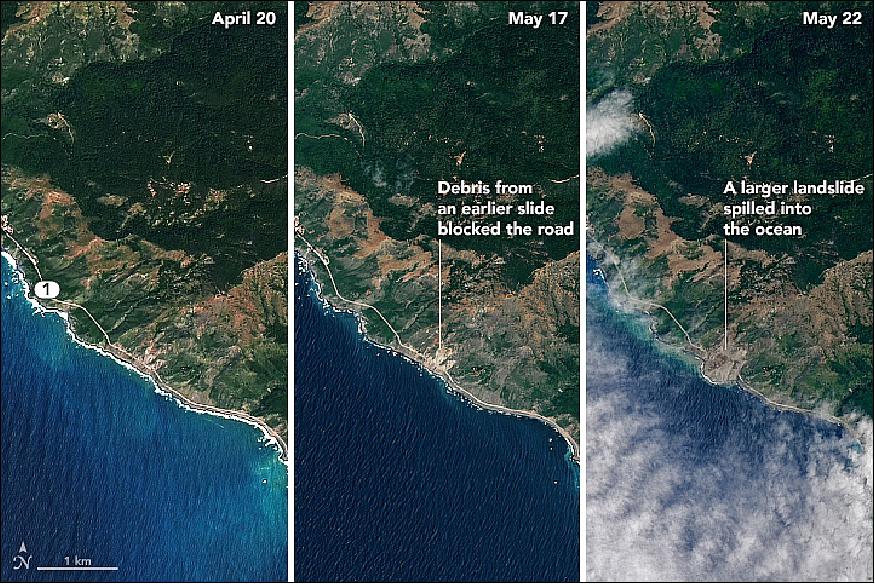

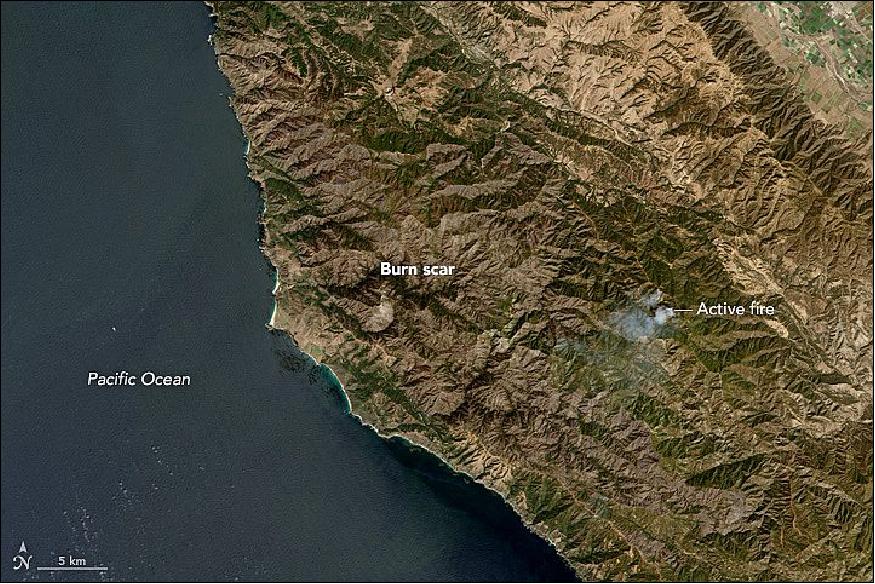

• May 25, 2017: A large landslide has strewn debris over a stretch of California's Highway 1. On the night of May 20, 2017, more than a million tons of rocks and dirt spilled over the roadway, according to the California Department of Transportation. 31)

- OLI ( Operational Land Imager) on Landsat 8, acquired images of the area on April 20 and May 22, 2017. The center image, acquired by a the MSI (Multispectral Imager) on the European Space Agency's Sentinel-2 satellite, shows the same location as it appeared after a previous, smaller landslide this spring.

- "This is a large slide preceded by smaller slides, which is not uncommon," said Thomas Stanley, a geologist and researcher for NASA, in an email. "Much of the California coastline is prone to collapse, so it's fortunate that this landslide happened in an unpopulated location." In 2015, the Monterey County Environmental Resource Policy Department rated parts of the nearby coast as highly susceptible to landslides.

- The latest landslide covered roughly one-third of a mile of the scenic route in 10 to 12 meters of rubble. The highway will remain closed for the foreseeable future, according to Caltrans.

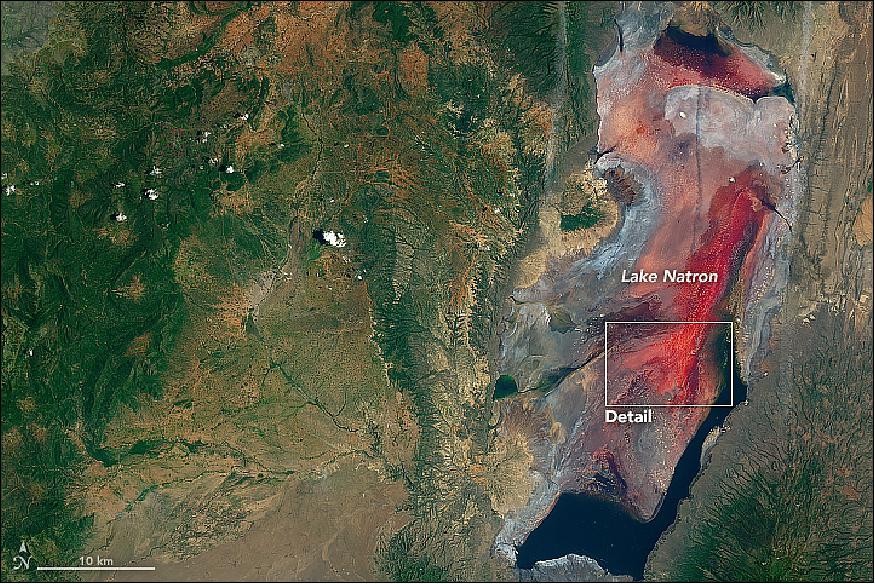

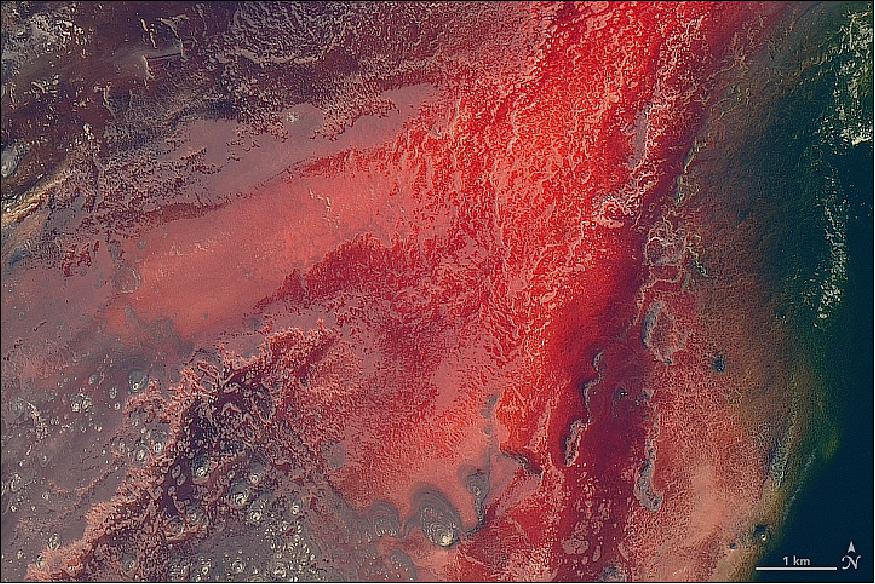

• May 8, 2017: Not many people venture near the shores of Lake Natron in northern Tanzania. The lake is mostly inhospitable to life, except for a few species adapted to its warm, salty, and alkaline water. 32)

- But you don't need to visit the lake in person to see its stunning, seasonal color. OLI (Operational Land Imager) on Landsat 8 captured these natural-color images of Lake Natron and its surroundings. They show the lake on March 6, 2017, very early in the rainy season that runs from March to May. In these images, you can see the deepest water along the perimeter of the lake bed, the location of lower-elevation lagoons.

- The lake is a maximum of 57 km long and 22 km wide. The climate here is arid. High levels of evaporation have left behind natron (sodium carbonate decahydrate) and trona (sodium sesquicarbonate dihydrate). The alkalinity of the lake can reach a pH level of greater than 12. In a non-El Niño year, the lake receives less than 500 mm of rain. Evaporation usually exceeds that amount, so the lake relies on other sources—such as the Ewaso Ng'iro River at the north end—to maintain a supply of water through the dry season.

- But it's the region's volcanism that leads to the lake's unusual chemistry. Volcanoes, such as Ol Doinyo Lengai (about 20 km to the south), produce molten mixtures of sodium carbonate and calcium carbonate salts. The mixture moves through the ground via a system of faults and wells up in more than 20 hot springs that ultimately empty into the lake.

- While the environment is too harsh for most common types of life, there are some species that take advantage of it. Small, salty pools of water can fill with blooms of haloarchaea—salt-loving microorganisms that impart the pink and red colors to the shallow water. And when the waters recede during the dry season, flamingos favor the area as a nesting site, as it is mostly protected from predators by the perennial moat-like channels and pools of water.

- Lake Natron is a salt and soda lake in the Arusha Region of northern Tanzania. The lake is close to the Kenyan border and is in the Gregory Rift, which is the eastern branch of the East African Rift. The lake is within the Lake Natron Basin, a RAMSAR Site wetland of international significance.

- The lake is the only regular breeding area in East Africa for the 2.5 million lesser flamingoes, whose status of "near threatened" results from their dependence on this one location. When salinity increases, so do cyanobacteria, and the lake can also support more nests. These flamingoes, the single large flock in East Africa, gather along nearby saline lakes to feed on Spirulina (a blue-green algae with red pigments). Lake Natron is a safe breeding location because its caustic environment is a barrier against predators trying to reach their nests on seasonally forming evaporative islands. Greater flamingoes also breed on the mud flats.

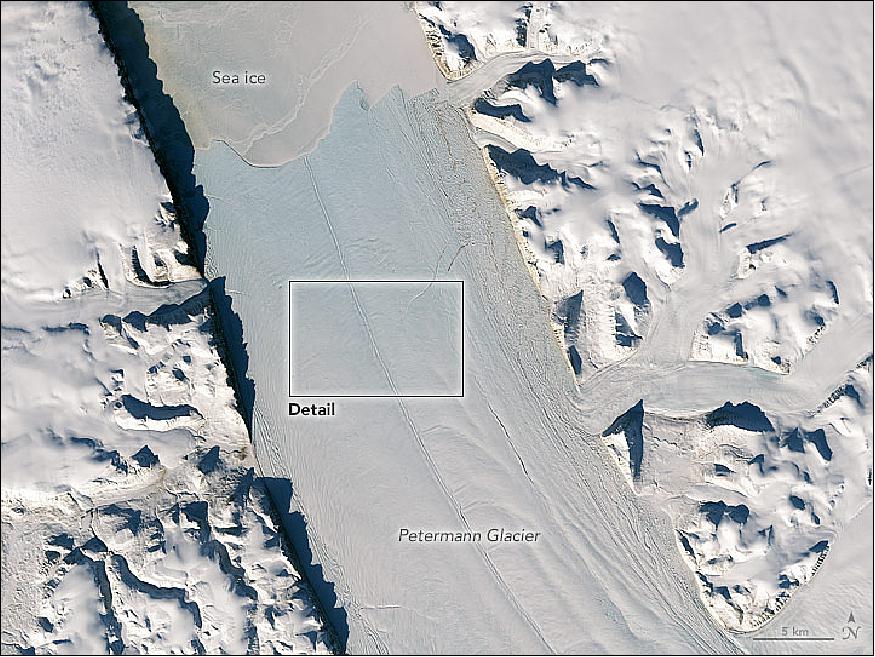

• April 19, 2017: The ice atop Greenland is not static. It slowly flows toward the coast and enters the ocean via outlet glaciers that ring the giant island. Petermann Glacier is one such "river" of ice. Like most glaciers that come in contact with the sea, Petermann has been known to periodically shed, or calve, icebergs. A new crack on the glacier has glaciologists watching Greenland's northwest coast closely. 33)

- The new crack, or "rift," is visible in these images acquired on April 15, 2017, with OLI (Operational Land Imager) on Landsat 8. The image of Figure 44 shows a wide view of the glacier, including its front—where the glacier's floating tongue meets the fjord's ice-covered sea water. The image of Figure 45 shows a detailed view of the rift.

- "Rifting and calving are normal," said Kelly Brunt, a glaciologist at NASA/GSFC ( Goddard Space Flight Center). "However, if this new rift crosses Petermann and calves a good chunk of ice, it would be the third such relatively large iceberg from this system in about seven years." It remains to be seen whether that will happen. Brunt points out that the rift currently appears to end at a feature running down the center of the glacier. "That's pretty typical," she said, citing similar occurrences on ice shelves in Antarctica.

- This new rift could eventually work its way through the feature in the center of the glacier. Or, the new rift could be met by an old rift—visible in the upper-right part of the detailed image—as it works its way from the northeast side of the glacier fjord. "But there is really no telling at this point," Brunt said.

- The day before the satellite images were acquired, Brunt flew with NASA's Operation IceBridge, an airborne science mission that conducts important surveys of snow and ice near Earth's poles. The flight had a number of goals, including an overflight of the recently discovered rift.

• April 16, 2017: This remote volcanic island has intrigued generations of scholars. Famed for its monolithic statues, Easter Island is shrouded in mystery. Its population, once sizable, collapsed (Figure 46). 34)

- "The clearest example of a society that destroyed itself by overexploiting its own resources," is how University of California Los Angeles geographer Jared Diamond once described it. But the island's history may not be as clear-cut as Diamond suggests. While scientists agree that broad-scale deforestation occurred here at some point, the verdict is still out on what exactly caused the downfall of the Rapanui people.

- Scholars do agree on one thing: the island once looked very different than it does today. Called Rapa Nui by its original inhabitants, it takes its English name from the day Europeans arrived: April 5, 1722—Easter Sunday. Dutch navigator Jacob Roggeveen reported a few thousand people living there at the time. He described this island, more than 3,000 km west of South America, as "exceedingly fruitful, producing bananas, potatoes, sugar-cane of remarkable thickness."

- Unbeknownst to Roggeveen, the indigenous population he encountered was just a fraction of its former size. Scholars estimate that between 15,000 to 20,000 people lived on Rapa Nui at the peak of its habitation. A thick cover of palm trees once shaded its hills, which are now fringed by low-lying vegetation.

- The extinct Terevaka volcano dominates the landscape, which also includes Poike and Rano Kau volcanoes and a number of smaller volcanic features such as lava tubes. Tufts of clouds pepper the sky overhead and a thick white outline along the island's southern edge indicates strong waves crashing against its shores. The Poike Peninsula, which juts out to the east, appears orange in places, a result of erosion exposing the brightly colored volcanic soil. The largest stand of trees, a eucalyptus plantation, was planted by people. Authorities hope reforestation efforts will help protect the island against the scouring wind.

- About 5,000 people live on Easter Island today, and thousands of tourists come to see the anthropomorphic "moai" statues each year. Amid strain from a rising population, the island faces challenges ahead. It has no sewer system and continues to draw on a limited freshwater supply.

• March 31, 2017: This month, 20 Landsat scenes were ingested by the USGS Hazard Data Distribution System to provide data for Charter activations: 35)

The International Charter is a system that supplies free satellite imagery to emergency responders anywhere in the world. The Charter concept is this: a single phone number is made available to authorized parties providing 24/7 contact to a person who can activate the charter. Once activated, a project manager takes charge. The project manager knows what satellite resources are available, how to task them to collect data, and how to quickly analyze the collected data to create impact maps for first responders. These maps, provided to responders for free, often show where the damage is and where crisis victims are, allowing responders to plan and execute relief support.

You can think of the Charter as a one-stop-shop for impact maps—an essential resource, since in many cases satellite data are the only practical method to assess current ground conditions after a disaster.

• March 18, 2017: Several hundred lakes dot the expansive Tibetan Plateau. With the average plateau elevation exceeding 4,500 meters above sea level, its lakes are among the highest in the world.

- Puma Yumco in Lhozhag County is one of the larger lakes in southern Tibet. A small village along the eastern edge of the lake—Tuiwa—is reportedly one of the highest administered settlements in the world, sitting at an elevation of 5,070 meters. Tuiwa's economy centers on raising livestock (sheep and yaks), tourism, and textiles. Though there are fish in the lake, they are considered sacred and are not eaten by most Tibetans. - Lake Puma Yumco is 32 km long and 14 km wide and covers an area of 880 km2.

- Every winter, villagers herd thousands of sheep across the lake's frozen surface to two small islands, where the soil is more fertile and the forage is better in the winter.

- While the rhythms of life have remained largely unchanged in Tuiwa for many decades, researchers have used satellites to track subtle changes at Puma Yumco and other lakes throughout the plateau. One team has found that the number of lakes on the Tibetan Plateau has increased by 48 percent, and the surface area of the water has increased by 27 percent between the 1990s and 2015. For Puma Yumco, the size of the lake dropped a bit between the 1970s and 1990s, but has risen since then, primarily because of an increase in precipitation.

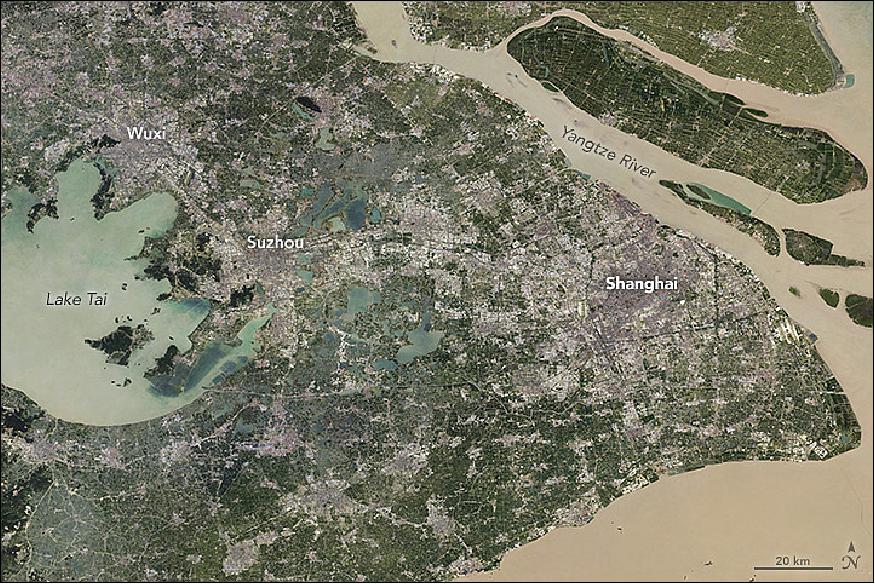

• March 17, 2017: Geographers who have studied the growth of China's cities over the past four decades tend to sum up the pace of change with one word: unprecedented. In 1960, about 110 million Chinese people—or 16% of the population—lived in cities. By 2015, that number had swollen to 760 million and 56%. -For comparison, the entire population of the United States was about 325 million people as of March 2017. 36)

- The surge in urbanization began in the 1980s when the Chinese government began opening the country to foreign trade and investment. As markets developed in "special economic zones," villages morphed into booming cities and cities grew into sprawling megalopolises. Perhaps no city epitomizes the trend better than Shanghai. What had been a relatively compact industrial city of 12 million people in 1982, had swollen to 24 million in 2016, making it one of the largest metropolitan areas in the world.

- For more than four decades, Landsat satellites have collected images of Shanghai. The composite images of Figures 48 and 49 show how cities in the Yangtze River Delta have expanded since 1984. Note how Suzhou and Wuxi have merged with Shanghai to create one continuous megalopolis (Figure 49).

- These "best-pixel mosaics" are made up of small parts of many images captured over five-year periods. The first image is a mosaic of scenes captured between 1984 and 1988; the second shows the best pixels captured between 2013 and 2017. This technique makes it possible to strip away clouds and haze, which are common in Shanghai.

- A 2015 World Bank report noted that 7,734 km2 in the Yangtze River Delta Economic Zone—which includes Shanghai, Suzhou, Wuxi, and several other cities—became urban between 2000 and 2010. That is an area equivalent to 88 Manhattans. During that period, population in that zone increased by 21 million people.

• March 15, 2017: Along the western border of Virginia, two roughly parallel ridges—one of which is the backbone of Shenandoah National Park and the other part of George Washington National Forest—rise above the rolling lowlands of the Shenandoah Valley. Despite being just a few kilometers apart, the ridges show some marked differences (Figure 50). 37)

- With a perimeter of smooth, straight crests encircling a valley, Massanutten Mountain has the look of a flat-bottomed canoe. Shenandoah National Park's portion of the Blue Ridge, in contrast, has a more textured, irregular, and knobby shape; it looks more like a spine, with a dendritic network of gullies descending from its main crest.

- The two ridges look different due to distinct geological histories. The rock underneath Shenandoah National Park is largely igneous, meaning it was created when magma or lava cooled and solidified. Some of the oldest rocks in the park are granites that formed deep underground about 1.1 billion years ago when continents collided and pushed up a mountain range during the Grenville orogeny. Major outcrops of granite are located east of Shenandoah's highest crest and dominate peaks such as Old Rag and Mary's Rock.

- About 500 million years later, the tectonic tides had shifted. Instead of continents colliding, they were pulling apart. As the crust thinned and rifts formed, volcanoes sprang up and spilled lava across the land surface. This laid down layer upon layer of basalt, a type of igneous rock that cools quickly and thus has small mineral crystals. When exposed later to the high temperatures and pressures associated with the collision of tectonic plates, the basalt metamorphosized into metabasalt. This greenish rock, known in this area as the Catoctin Formation, makes up much of the Blue Ridge's highest crest, including peaks like Hawksbill, Stony Man, Mount Marshall, and Hightop.

- As the rift widened, it eventually connected with the ocean and was filled by a narrow, shallow sea. At its bottom, sedimentary rocks began to form as layers of sand, mud, and material from sea life began to rain down on the sea floor and become sandstone, shale, and carbonate rock.

- The landscape we see today was set up by one more cycle of continents slamming into each other—a collision between North America and Africa about 300 million years ago known as the Alleghanian orogeny. While building mountains that were once as tall as the Himalayas, the Alleghanian orogeny thrust the older igneous rocks (once the root of the Grenville range) upward and squeezed them into a curved bulge called an anticline, putting older rock layers quite close to the surface. The same collision squeezed and folded the nearby rocks of the Shenandoah Valley and Massanutten into a concave depression called a syncline that kept the youngest sedimentary rocks quite close to the surface.

- With the rock layers in place, erosion played the final role in sculpting the modern landscape. Rivers such as the Shenandoah's South Fork wore away relatively soft and weak types of sedimentary rock (the shale and carbonates) to create low-relief areas such as the Shenandoah Valley, Page Valley, and Fort Valley. Erosion-resistant, quartz-rich sandstone remained to give Massanutten Mountain its distinctive shape. To the east, the erosion-resistant igneous-based rocks of the Blue Ridge tower over Shenandoah Valley, Massanutten Mountain, and the rest of the Piedmont.

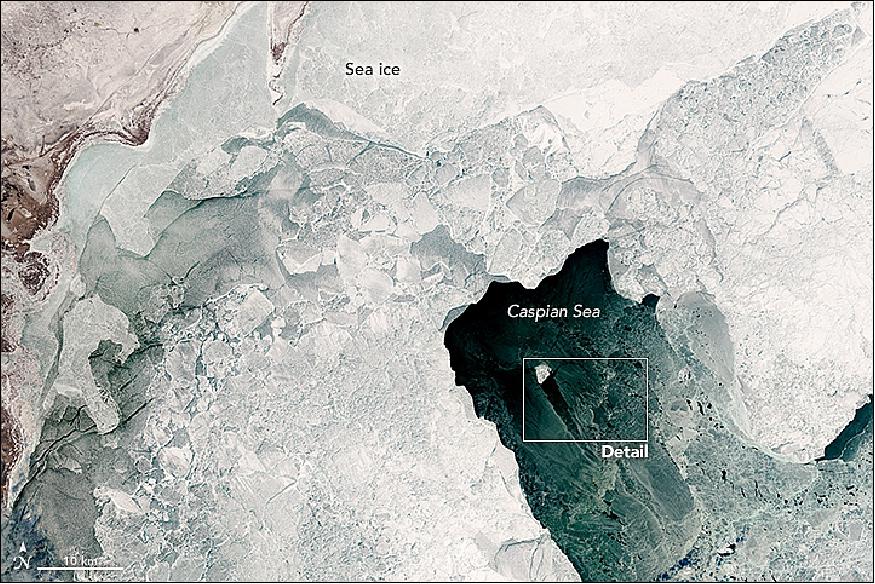

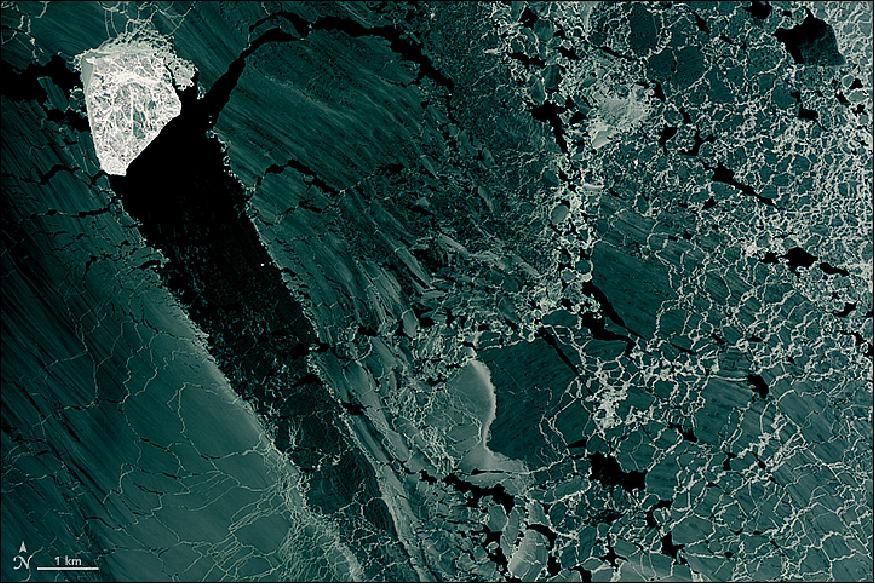

• March 1, 2017: The Caspian Sea stretches about 1,000 km from Kazakhstan to Iran. In the north, temperatures are colder, and the water is fresher (less saline) and shallower. As a result, northern areas are more prone to freezing in wintertime. 38)

- The image of Figure 51 shows the northwestern Caspian where it meets western Kazakhstan. The brown areas are part of the Volga Delta. Just offshore, in the shallowest parts (only meters deep), a well-developed expanse of consolidated ice appears white. Farther offshore, a large field of old, hummocked, white and gray-white ice has detached. (When pieces of ice are pushed together, some ice is forced upward and downward into so-called ‘hummocks.') This ice is slowly drifting in a giant polynya which is covered by young, thin ice (nilas).

- The image of Figure 52 shows a detailed view of the nilas ice, which appears dark. Perhaps most notable, however, is the white, diamond-shaped piece of ice parked right in the middle. "This ‘island' of white ice is most probably a piece that detached from the ice field," said Alexei Kouraev, a scientist at the Laboratory of Geophysical and Oceanographic Studies (France). He notes that a likely point of origin is the "dent" of similar size in the boundary of the white ice (mid-right in the image of Figure 51).

- It might look like that ice diamond is on the move, cutting a path through the thinner cover. But it's more likely that the chunk of ice broke away from the thicker sea ice and became grounded—anchored to the bottom of the sea. The grounded ice (‘stamukha' in Russian) is not moving, according to Kouraev. Instead, the wind is pushing the thin ice around this grounded ice, creating a ‘shadow' of open water behind it.

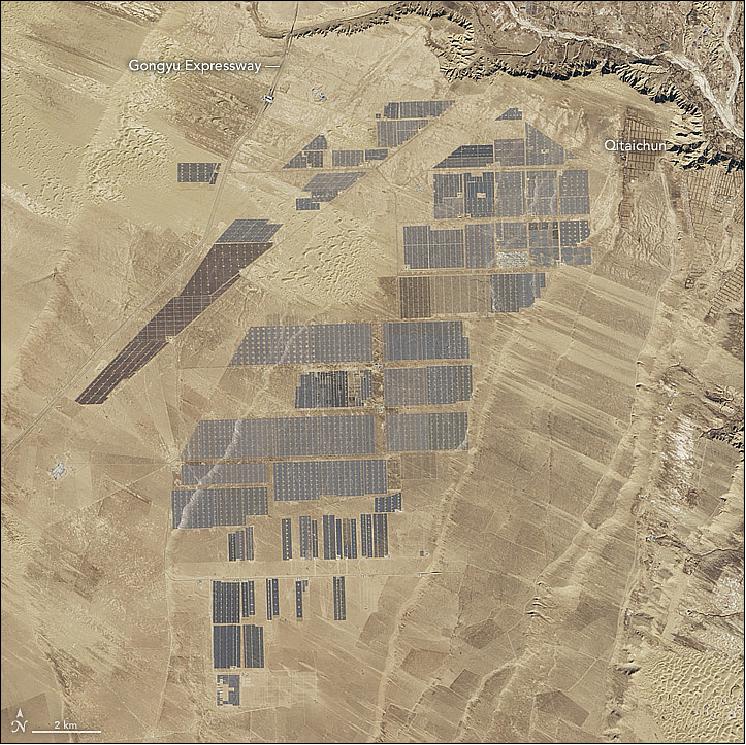

• February 16, 2017: In the past few years, the title of "largest solar farm in the world" has been a rather short-lived distinction. For a period in 2014, the Topaz Solar Farm in California topped the list with its 550 MW facility. In 2015, another operation in California, Solar Star, edged its capacity up to 579 MW. By 2016, India's Kamuthi Solar Power Project in Tamil Nadu was on top with 648 MW of capacity. — As of February 2017, Longyangxia Dam Solar Park in China was the new leader, with 850 MW of capacity. 39)

- By January 5, 2017, solar panels covered 27 km2 of the Qinghai province in China (Figure 53). According to news reports, there were nearly 4 million solar panels at the site in 2017. The rapid expansion at Longyangxia coincides with China's fast-growing solar power sector. In 2016, China's total installed capacity doubled to 77 GW. That pushed the country well ahead of other leading producers—Germany, Japan, and the United States—to become the world's largest producer of solar power. However, those three countries (and several others) produce more solar power per person.

- It is unlikely that Longyangxia will remain the largest solar park in the world for long. A project planned for the Ningxia region in China's northwest will have a capacity of 2,000 MW when it is finished, Bloomberg reported.

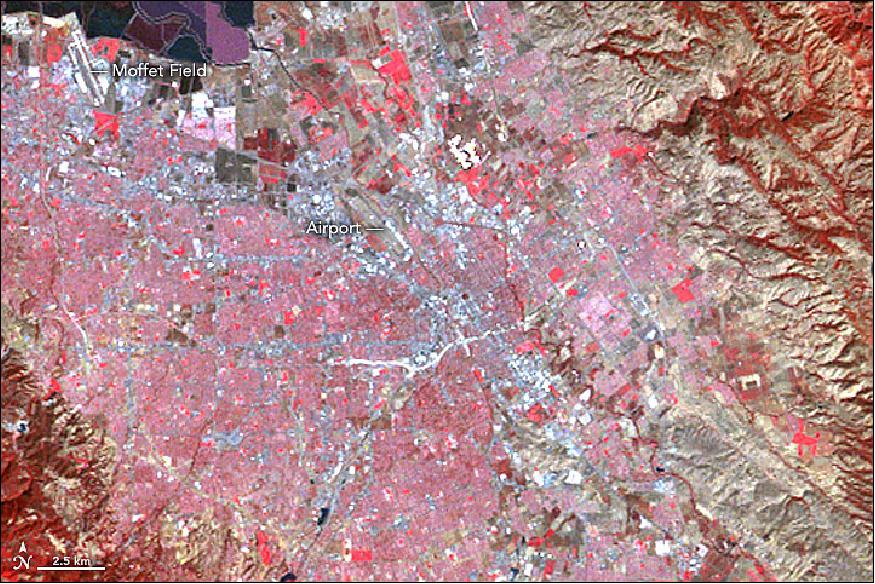

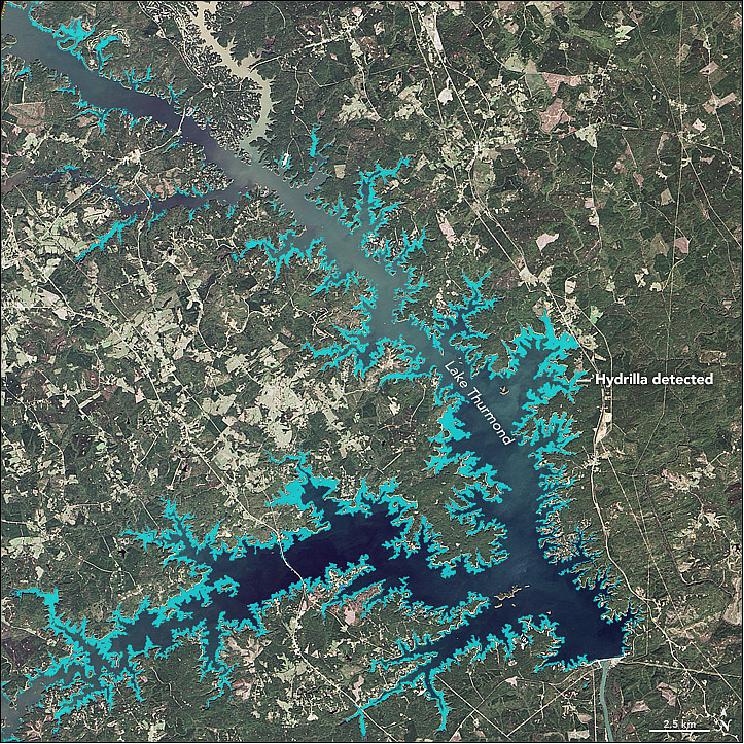

• February 5, 2017: Image comparison of Silicon Valley observed by Landsat-1 in 1972 and by Landsat-8 in 2016.

By the middle of the 20th Century, Silicon Valley was already "on the map." This part of California's Santa Clara Valley drew its nickname from the raw material being used in the region's growing semiconductor industry. The area at the south end of San Francisco Bay became a magnet for scientists and for technology companies, so by the time the new Landsat-1 satellite caught a glimpse in 1972, urban sprawl had already replaced many of the valley's orchards. 40)

- While the two images of Figures 54and 55 don't show much change in the development of the landscape, they clearly show the development of the technology behind Landsat's satellite sensors. The false-color image of Figure 54 was acquired on October 6, 1972, with the MSS (Multispectral Scanner System) on Landsat-1; the natural-color image of Figure55 was acquired on November 18, 2016, by the OLI (Operational Land Imager) on Landsat-8.

- The most obvious improvement is the spatial resolution. Over the past 45 years, you have certainly noticed similar improvements in your electronics and imaging products. Better spatial resolution is the reason you can now see blades of grass in a televised football game and the fine lines on your face in a smartphone photo. In short, there is a lot more detail visible in the 2016 image than in the 1972 image. Both are displayed at a resolution of 45 m per pixel. The MSS image is relatively blurry, however, because the sensor's spatial resolution was just 68 x 83 m. The OLI image appears crisper because the instrument can resolve, or "see," objects down to about 30 m (15 m in some cases).

- The 2016 image also has better radiometric resolution, which means the newer instrument is more sensitive to differences in brightness and color. OLI uses 4,096 data values to describe a pixel on a scale from dark to bright. MSS used just 64. More data ultimately translates to the features in the image appearing smoother.

- Finally, the images are very different colors because the wavelengths (color) of light used to compose the images are from different parts of the spectrum. Both images were composed using red and green wavelengths. The image of Figure 54, however, uses near-infrared. False-color images like this one (MSS bands 6, 5, 4) are still produced with modern instruments because they are useful for distinguishing features such as vegetation, which appears red in the top image.

- In contrast, the OLI image does not show near-infrared (although the instrument does have the capability). Instead, it includes blue, a color that MSS was not designed to sense. This combination (OLI bands 4, 3, 2) produces a natural-color image similar to what your eyes would see.

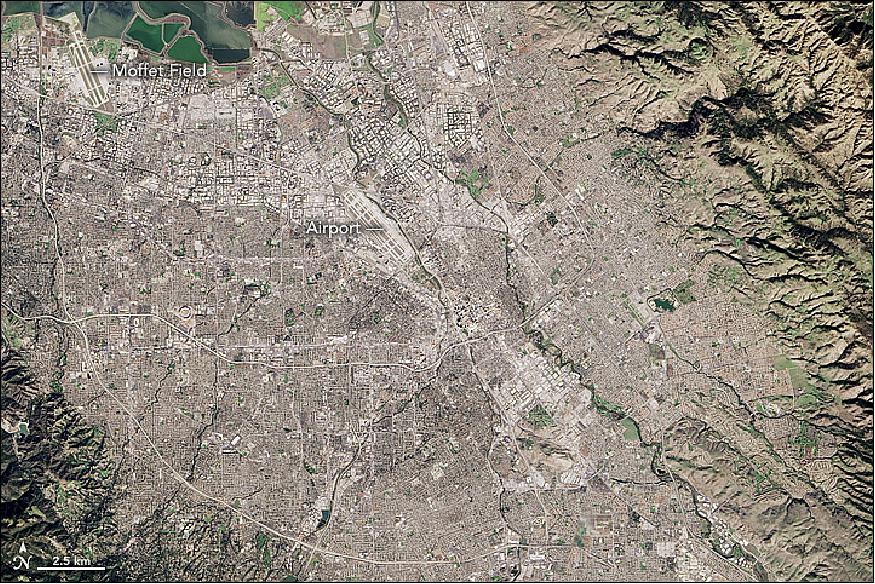

• January 27, 2017: Mariners have long considered the waters off Africa's southern tip to be treacherous. After decades of failed attempts to navigate around the continent, Portuguese explorers took to calling one of its southerly promontories the Cape of Storms (it was later renamed the Cape of Good Hope). Cape Agulhas , Africa's southernmost point, is Portuguese for Cape of Needles. Historians think the name may be a reference to the needle-like rock formations and reefs along its coast. 41)

- The convergence of two ocean currents—one warm and one cold—in the shallow waters of Agulhas Bank produces turbulent and unpredictable waters. Warm water arrives from the east on the fast-moving Agulhas Current, which flows along the east coast of Africa. Meanwhile, the cooler, slower Benguela Current flows north along Africa's southwestern coast. That means navigating around the tip of South Africa requires mariners to sail against ocean currents on both sides of the continent.

- Eventually, they learned to stay well out to sea as they rounded the Cape of Good Hope and Cape Agulhas, but not before failed attempts had littered the area's reefs with wrecked ships. Even in modern times, shipwrecks are relatively common in the turbulent water of Agulhas Bank, where colliding currents regularly spin off rogue waves, eddies, and meanders.

- The instability and churning does have one benefit. As water masses stir the ocean, they draw nutrients up from the deep, fertilizing surface waters to create blooms of microscopic, plant-like organisms (phytoplankton) in the open ocean. The phytoplankton feed a robust chain of marine life that makes Agulhas Bank one of the richest fishing grounds in southern Africa.

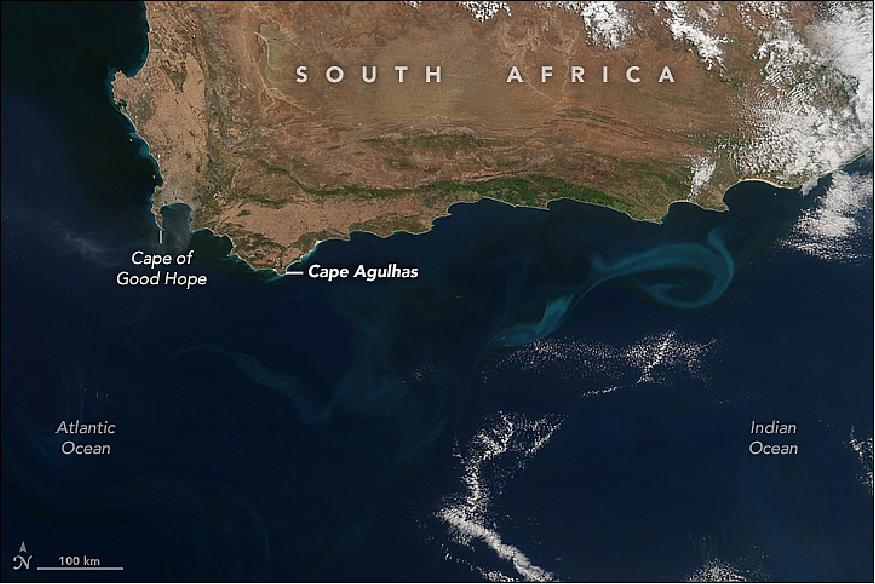

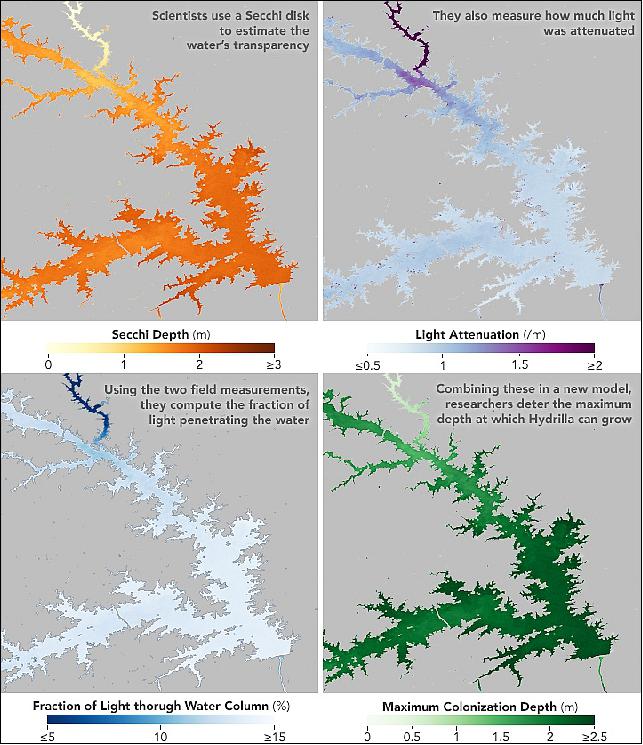

• January 4, 2017: Around Lake Thurmond, a large reservoir that straddles Georgia and South Carolina, something is not right with the birds. The lake is full of vegetation — particularly an invasive aquatic plant known as Hydrilla verticillata — and the area is full of birds that are distressed or dying. 42)